Points of View: An Interview with Zoe Whittall

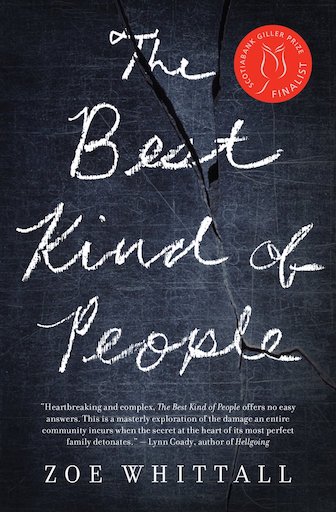

Zoe Whittall’s latest novel, The Best Kind of People, is unapologetically topical: it explores accusations of rape in small-town America that result in rampant victim-blaming and a community in shreds.

George Woodbury, a well-liked teacher and family man, goes on trial for sexually assaulting a number of his female students, shocking his family and creating rifts across their affluent neighbourhood. Normally a highly efficient and capable nurse and mother, his wife, Joan, is left without support, unable to relate to her former friends and peers. Daughter Sadie, precocious and introspective, faces her father’s alleged victims every day at school; eldest son, Andrew, is forced to return from New York to his insidiously homophobic hometown in order to stand by his family through the upheaval. Through the eyes of this Woodbury ensemble cast—neglecting only George’s perspective—the novel investigates what happens when trusting the person you love just isn’t enough.

Born and raised in Quebec’s Eastern Townships, Zoe Whittall is the author of half a dozen novels and poetry collections. The Best Kind of People (House of Anansi Press) has just been longlisted for the Giller Prize. Through email, I spoke to her about the culture around sexual assault and her decision to exclude George’s perspective from the narrative.

Lucy Uprichard: There have been a lot of high-profile cases regarding sexual assault and rape in the news over the past few years, many of which have taken place in schools and universities. Was there any one incident that led you to writing The Best Kind of People?

Zoe Whittall: Not one incident, no, though I followed all high-profile cases very carefully while writing the book. I began writing the character of Joan as an experiment on a day when I was having writer’s block about another novel I’d started earlier. She was inspired by a program on The Current about a therapist who ran a group for women who want to stay with partners who are in prison or accused of sex crimes, and want to try to work it out anyway. I found that fascinating, to know the worst and to want to stay. Why would you ever make that decision? That was the question I started with. I’ve always been interested in partners with secrets, or the ways that people can be unknowable, even in relationships.

LU: Unlike a lot of other novels that deal with similar themes, we never see George’s perspective and he doesn’t get a chance to tell his side of the story. Shortly after his arrest, Joan feels that “nothing, not even a revolving camera of omniscience, a floating momentary opportunity to narrate, would allow anyone to truly understand the truth about George.” What led you to exclude him from the narrative? Was it a deliberate attempt to go against the grain of how these stories are usually told? Do you think the perpetrator’s “truths” in these stories are always unknowable?

ZW: I didn’t want to write a crime novel, or a survivor novel. There are a lot of great books out there already telling stories from the perspective of the accused, or the victim. I wanted to tell the story from the perspective of the person who opens the door when the cops come and watches their loved one get arrested. I purposely didn’t want George to be knowable, because that was the experience the family was having, a feeling of distance and confusion and projection, of not being able to know him. Once someone becomes known in the media they become difficult to know, in general, and especially in this kind of case. When your friend or family member is accused of something terrible, or you discover a lie or manipulation, there is a real feeling of disruption in the way you think you know someone, or can know someone, so I wanted the book to be make that feeling come alive.

I also suppose that in another way, I didn’t want to give George a voice of his own on purpose. We’ve heard from the Georges of the world for a long time in literature. I did write drafts of the book with chapters from his perspective, I wrote out his extensive backstory. I needed, as the author, to know exactly who he was in order to write something authentic, to understand what his motivations were, what he valued and how he became himself. But I didn’t need to include those details. They just needed to inform the story so that the fragments of George’s story that I did include ended up making sense.

I also didn’t want to describe the crimes and contribute to the voyeuristic thrill that books or films about rape often indulge in. I watch a lot of Law & Order SVU, and it’s known as a show that survivors love because it’s an aspirational fictional world where victims are listened to and believed, and justice is served, so to speak. But there’s also something kind of exploitive about it. I’m not drawn to depictions of violence in general—I won’t watch horror films and I tend not to read anything too gory. We don’t have to be drawn an explicit picture all the time, especially not with this particular story that I wanted to tell.

LU: Almost all the characters in The Best Kind of People are reasonably well-off and the school that Sadie attends and George taught at is a “prestigious prep school.” What made you choose a relatively rich and conservative small American town as your setting for this novel, when your previous books have largely been set in larger, metropolitan Canadian cities?

ZW: I can’t remember the moment I decided to make them wealthy or why I did it, it just felt right at the time. I wanted there to be a sense that the family had it pretty easy before this happens, they were secure in every sense, there was a lot to lose.

I also wanted to write a book that was far from my reality and see if I could do it. My other novels aren’t autobiographical in any way, but their settings are familiar to me, and the characters are people I could easily know in my life. That was a very important thing for me to do—there are still so few authentic depictions of queer and trans people in literature—but I wanted to set a new creative challenge for myself with this book.

This meant I called a lot of my friends who were either American or had grown up wealthy to ask weird questions while I was writing it. I looked at a lot of prep school websites to try to imagine the school.

LU: It may just be the prevalence of such things on social media, but it certainly seems that young women and girls in schools and on university campuses are taking a really active stand about issues like slut-shaming and sexual assault and harassment nowadays. Do you think the discourse around blame and guilt and power in these situations is changing at all?

ZW: It’s hard to know what is changing and what isn’t, on a systemic level, because of the increase in conversation about consent and violence, but the proliferation of writing and publishing on the subject is fantastic to me. The two thirteen-year-old girls who started a consent education program in Toronto—amazing! I hope that there’s a real shift that’s happening around consent with young people today, and in ways that will result in changes to systemic misogyny. I don’t see that happening right now, but I think it’s on its way.

LU: Throughout the course of the novel, the characters are put in situations that force them to choose between their untested theoretical stances on sexual violence and their feelings towards their family. Joan in particular struggles with this, as believing the accusations and aligning herself with “faceless police and children she didn’t raise” means turning her back on her husband and the life that she has built with him. Given that The Best Kind of People reads like something of a modern morality tale as applied to rape culture, are there any lessons that you intended your readers to walk away with?

ZW: No, I didn’t have any lessons in mind. I wanted to tell an interesting story and that’s all. I had to stop myself any time I had an urge to make a particular political point, because that’s when storytelling flounders. Of course my sensibilities and my thoughts about rape culture are revealed in moments through various characters, but I never wanted to write a book that was educational or moralizing.

Lucy Uprichard is a research intern at Maisonneuve.