Overturning Scarcity

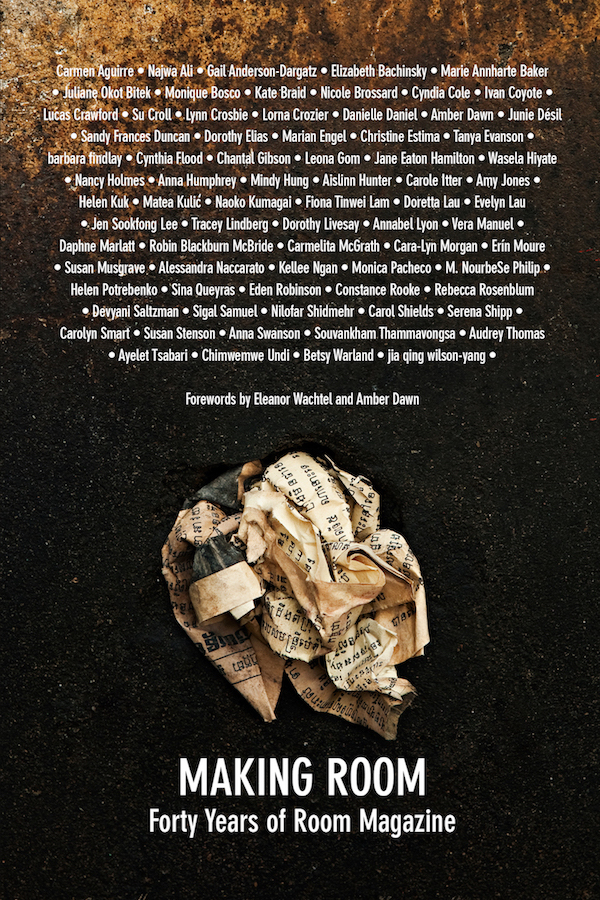

Editor’s note: The following essay is an excerpt from Making Room: Forty Years of Room Magazine, an anthology that celebrates the fortieth anniversary of the feminist literary journal Room. Featuring seventy-five contributors and spanning the four decades of the journal’s existence, the anthology is a remarkable contribution to, and reflection of, contemporary Canadian literature.

Throughout my forty-two years of living, I’ve spent a lot of time with shame. But I’ve only felt ashamed of my writing once. It didn’t take volumes, or even pages, to provoke this feeling. All in all, it was only a few words within a poem. I had changed the pronouns in a love poem from “she” to “he”—making the poem’s narrative appear decidedly heteronormative.

I wasn’t exactly a new writer at the time; however, the goal of building a writer’s CV was new to me. Getting published is what we do, right? We get the work out there. We garner literary magazine publications, as many as possible, eventually leading to that coveted first book deal.

This vocation wasn’t going so well for me. My work was, and still is, a three-pronged praxis of queer identity, individual and systemic trauma, and sex work justice, themes drawn from my own lived experience and cultural knowledge base. While this made me something of a unique darling on the poetry stage and an “it girl” at book parties, I had been rejected by almost every Canadian literary magazine, coast to coast.

Publications with the staff or volunteer capacity to include a personal note alongside their rejections were seemingly encouraging—I was always invited to submit again because the writing I had sent was “not a fit” for their magazine. After a fair few of these notes, the phrase “not a fit” became less and less sharp, and more and more curious.

Was it my effusive use of words like “rape” or “cunt” or “slut” that was not a fit, I wondered? Was it my sexuality? Was it me? I investigated by un-queering a poem, altering only the pronouns, so that the female narrator in the poem was speaking to a male recipient of her desire. With this pronoun change I resubmitted to the same Canadian literary magazine that had previously rejected me, and that year I saw my first professional publication. Except I don’t refer to it as my first professional publication (that sounds like a cause for celebration). I refer to it as the poem that was edited by shame.

I grew up white, poor, and surviving trauma in a small village that frequently winds up the list of Canada’s poorest postal codes. I was educated in scarcity, by the idea that there simply isn’t enough for all of us to have resources or space or value. I learned that scarcity is both physical and psychological. For example, for a good part of my childhood, my single mom and I lived in an attic where neither of us had bedrooms. We could not afford physical space; we could not afford rooms of our own.

A psychological example? Well, those examples are endless. For the purpose of brevity, I’ll pick one memory. When I was an awkward, runty teenager in 1989 the federal government vowed to eliminate child poverty by the year 2000. I distinctly remember the pending changes to the mothers’ allowance program (a welfare program adopted by five provinces during much of the twentieth century) because my ma was crying as she filled out the new application form. Would the new program be any better? Would she still receive a monthly government cheque? In our village, the cluster of single mothers that it is, my ma wasn’t the only one with questions. As the questions spread, they snowballed into scarcity conflicts—with mothers of colour and Indigenous mothers and white mothers and newcomer mothers systemically pitted against each other. (Many unemployed men in the village were already incredulous toward mothers for receiving government cheques in the first place.) I remember how these scarcity conflicts trickled down into schoolyard gossip and tension. I cannot report on who actually collected welfare and who didn’t, nor would I want to. All I can say is that the year 2000 has come and gone and child poverty in Canada has risen. The personal anecdotes I share with you are in no way unique. In fact, statistics show us that scarcity is growing.

Sometimes I try to imagine these estimated 1,331,530 poor children, as individuals, and also as a growing population of people psychologically conditioned by scarcity. Some of them will grow up to be poets, like me. Maybe they will send their work out there, like I did. And if and when they receive rejections with messages that their work is “not a fit,” will those messages feel so painfully familiar, like they did when I received them?

When I was a not-so-new, but unpublished writer, I discovered that CanLit wasn’t all that different from the village I grew up in. It is a landscape of scarcity. There are simply not enough publishing opportunities (or book reviews or grants for writers or invitations to literary festivals) to go around.

It may be a distant parallel, but I nonetheless have drawn an apt comparison between my ma crying while filling out a new welfare application (an origin story of my shame) and me editing out my queer truth in a poem so that CanLit might accept me.

While I am currently grateful for my decade-long run of seeing my work published, I can still say with great assurance that scarcity shapes CanLit. And who receives the bulk of rejections or messages that the writing is not a fit? Women of colour, Indigenous women, queer and trans women, and women whose writing explicitly explores trauma or difference.

I’ve witnessed literary agents, editors of large Canadian publishing houses, and creative writing program chairs alike try to address the glaring gap in diversity in our literary communities with bewilderment and defensiveness. Each time I see a literary professional with some degree of power respond to “why does CanLit lack diversity?” like it is a dirty question, I feel that same scarcity panic, that shame.

For the many women authors who read this, and for those readers who believe that there is an unjust bias in CanLit, you will hardly be surprised that change is occurring, because diverse writers are creating our own opportunities. The incredible thing about psychological conditioning—like the very idea of scarcity—is that we also have the capacity to learn new messages and to create change. For forty yearsRoomhas been at the forefront of this change.

Room changed CanLit when Cyndia Cole’s groundbreaking “No Rape. No” was first published in the 1970s. Room has shown CanLit that women’s complex bodies are indeed a fit, with fiction like Juliane Okot Bitek’s “The Busuuti and the Bra” and with poems like jia qing wilson-yang’s “trans womanhood, in colour.” Room continues to recognize that trans and non-binary gender narratives are an inherent and esteemed part of feminist literature by calling attention to Ivan Coyote’s “My Hero” and Lucas Crawford’s “Failed Séances for Rita MacNeil.” By honouring work like Doretta Lau’s “Best Practices for Time Travel” and Eden Robinson’s “Lament,” Room challenges tired notions that social justice and Indigenous speculative fiction are anything less than synonymous with great literature.

Room’s anthology—which includes each of the works I mentioned above—is a timely collection of seventy-eight exceptional literary works. Scarcity and shame have not claimed a single page, not a single line or word of it. Its readers, and I, and the seventy-five remarkable contributors are both teaching and learning a new message, right now. Say it with me. There is Room. We do fit.