Nerve: An interview with Eva Holland

When I was four or five years old, I stood at the top of an escalator at The Bay, or maybe it was Sears, frozen. My dad was ahead of me, tilting my baby sister upwards in her stroller.

I couldn’t move. I thought my sister would fall slowly out of the stroller’s harness, headfirst onto the corrugated escalator step. A woman behind me picked me up, plopped me onto the escalator, probably swearing at my dad in French. Years later, I fell down an escalator at a Montreal shopping complex, holding a blue slush and ice skates. I’ve been afraid to step on an escalator with my hands full ever since.

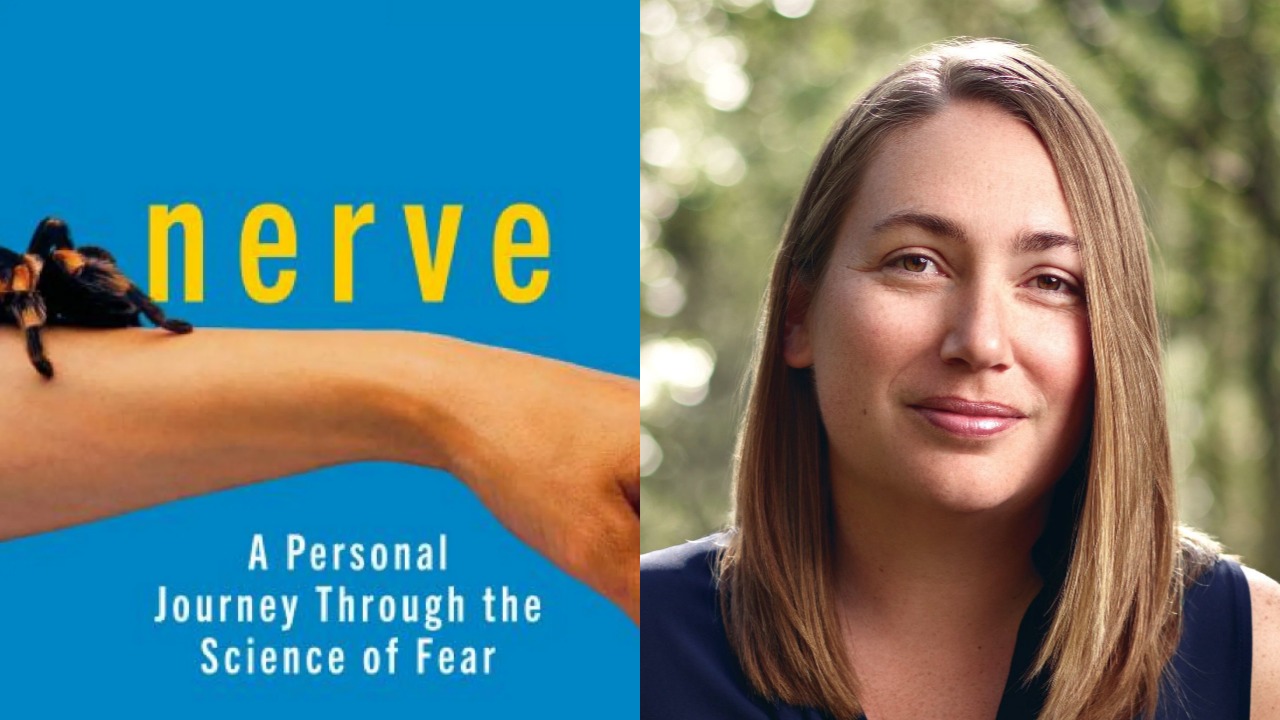

In her latest book, Eva Holland makes us confront our deepest fears by detailing her own: escalators, heights, driving, and most of all, the death of her mother. She released Nerve: A Personal Journey Through the Science of Fear (Penguin Random House Canada) in April after four years of researching and writing about her adventures, worries and sorrows.

Holland is a freelance journalist and outdoors enthusiast based in Whitehorse, Yukon. After years of telling other people's stories, reporting a book about fear meant turning inwards and learning to ask hard questions about herself.

Chloё Lalonde: Why bother with trying to cure fears?

Eva Holland: I don't think we always have to try to cure our fears. I think it's about deciding to what extent they're leaking out into your life and to what extent they might be impairing you in doing what you want to do. It's a judgement call: is what I'm afraid of, and the consequences of that fear, worse than what I would have to deal with in trying to face it? Because the whole facing your fears thing is not easy. It's hard work. It's unpleasant. For me, it's about weighing those consequences against each other.

The example of the book of the woman who was afraid of mice. I think if she had been able to feel safe in her home knowing that it was free of mice, if she only freaked out when she actually saw a mouse—and her home was free of mice—then maybe she would have been okay. But she was terrorized by the possibility of mice to such an extreme extent. And so I think it's really about how that fear plays out in your life, and if you want to accept those consequences of that fear, or if you want to accept the consequences of trying to alter your fear.

CH: Where do you start to face your fears? Saying them out loud? Forcing yourself to do something out of your comfort zone?

EH: I think the first step is identifying that you’re afraid and what it is you're afraid of. Sometimes we have these reactions without even identifying and acknowledging the patterns. And so the first step for me was seeing the pattern and addressing it, particularly with heights [...] and car accidents—I had to identify that it was a problem and to admit it to myself and others before I could start to deal with it. And from there the next step really varies.

CL: How does fear, or sharing the same fears, bring people together?

EH: I think it's just such a relief to know you're not alone. Fear feels so isolating, and it can feel so embarrassing. Just in these interviews that I've done, I've heard from so many other people who are interviewing me who are afraid of heights. I spoke to somebody earlier this week who was also afraid of escalators since she was a little kid and I was like, “Oh my god, I thought that was just me.” Other people have come to me with the exact same thing [...] everybody thinks that their story is so original. You know, it's part of what makes us feel special sometimes. But also it's so isolating when it's a bad story. And learning that it’s a shared story, I always find really comforting, really validating.

CL: Despite your fear or heights, would you consider yourself an adrenaline junkie?

EH: I would not consider myself an adrenaline junkie. I know it sounds strange from the outside, but I feel like the things I do, I do with very incremental steps towards being prepared, and very careful thoughts about risk management. It sounds extreme to say that I have done a one-hundred-mile ultramarathon in the Yukon winter where it went down to -45 degrees. But I spent years trying to prepare myself physically and emotionally. So it didn’t seem to me like a high-risk action at the time.

CL: What goes into that preparation other than exercise training and, I guess, therapy?

EH: I did four months of physical training for the race. But the longer term thing was the mental and emotional preparation. So I did other extreme events in less dangerous conditions, like the Yukon River Quest seven-hundred-kilometre paddle in the summer. It’s safer, you're in a boat, you’re in a group, it’s the summertime, but you experience extreme exhaustion, hallucinations, pushing your body to its limits, all that sort of stuff. And so I felt like I was trying that in a safe way before I tried a higher risk event in February.

And then I did a story for Outside magazine about going to Polar Explorer School. And so I spent two weeks in Nunavut for that story learning how to survive in cold weather conditions and practicing skills on sea ice and camping out. We ultimately spent a week with a guide on sea ice. So that felt, in some ways, way more challenging than the race. By the time I got to the race, I had the emotional and mental preparation, the physical preparation, and the skills and knowledge in place to do it. So it didn’t feel like it was an adrenaline event for me. I know that sounds strange because it’s still an extreme thing to me.

CL: Would you still be doing all these things if you hadn’t written Nerve?

EH: I think so, yeah. I started doing a lot of these things before I had the idea for the book. I think that working on Nerve probably helped equip me better for some of them. But I think I’d still be doing them regardless.

CL: It took you years to write this book. How do you feel about its release during a time none of us could have possibly anticipated? How do you think this current situation might be conditioning fear in us, changing social fears and emotions?

EH: I was pretty upset to realize that my book was going to be coming out in the middle of a global pandemic. I think it is timely in certain ways, even though I never imagined this context at all when I was working on the book. But I hope that it’s useful for people who are thinking a lot about fear and anxiety right now to read the book. I hope, even though it was written without me thinking about a pandemic context, that it has something to say for our moment. So I guess I’ve kind of come to terms with the timing.

I do think that this is an event that is going to change a lot of people’s relationships with fear and anxiety and trauma. You know, the caveat that large portions of the world were already very familiar with day-to-day uncertainty and danger. They couldn't count on their health, and they couldn't count on their business remaining stable, and their job and all that sort of stuff. But for those of us who aren't used to that kind of constant uncertainty, this is a real change and it’s going to have consequences for sure.

CL: Tell me about the cover: a tarantula crawling up a hand, a stereotypical phobia. I wouldn’t take you, as an outdoorsy person, as one who is afraid of creepy crawlies. Where did the concept for the cover come from?

EH: There's an experiment involving spiders pretty late in the book. But I wasn’t totally privy to the thought process behind the cover. I think they were trying to channel a shorthand that a lot of people can relate to [...] what does fear in a single image look like? And I think they hit on something pretty universal. You know, not many people are comfortable with the idea of a tarantula crawling on your arm. I think that’s a useful shorthand and a very striking image.

CL: Have you ever had a fear of creepy crawlies?

EH: I am generally sort of moderately averse to bugs, but not freaked out. Like I don't like them. I'm not comfortable around them, but they don't require a strong reaction, with the exception of earwigs. Earwigs and roaches.

CL: Do you have any creepy-crawly stories?

You know, the nice thing about being in the SubArctic is you have a relatively narrow spectrum of fauna here, so don't get a huge array of creepy crawlies. I've had some bad mosquito experiences for sure. I had a river trip a few years ago where I came off the river with somewhere between two and three hundred mosquito bites on my body. Now when mosquitoes swarm around me I feel a bit panicked, like maybe they're gonna suck me dry and kill me.

CL: You were born in Ontario. Why the move to Yukon? When and why did you make that decision?

EH: I have a cousin here about my age and I came to visit him, eleven years ago this summer, to check things out. And then I moved here a few months later. I was looking for a home base. I had become a freelancer and I could live anywhere in the world, basically. And I was looking for somewhere that would not be my hometown, Ottawa. I had gone back there after grad school to start to freelance, but it seemed like a waste of an opportunity to stay that close to home. I wanted someplace that was different and felt like a bit of an adventure.

The reason I chose Whitehorse, well, two things: I thought it would be a good place to be a freelancer as far as having access to Alaska, Northern BC and the territories, where there are lots of good stories and relatively few people telling them. The other thing was that the community here was so wonderful and supportive. A lot of those people that I first met here are still my closest friends. So I decided to stay and that’s why I’m still here.

CL: If you had to live and work from any other place in the world for the rest of your life, where would that be and why?

EH: Somewhere in the Pacific Northwest, maybe Vancouver Island or you know, border issues aside, the Seattle area. I would love to live by the ocean someday. It’s closer to Whitehorse than you would think. The Pacific Northwest rainforest continues all the way up the coast and Alaska. And in ordinary non-pandemic time, I go to the coast regularly and it's a place where I feel comfortable and I really enjoy those landscapes. You know, I'm only 120 kilometres from coastal Alaska here. It’s a ninety-minute drive, when the border isn’t closed. So it's a landscape that I really enjoy and a culture, a lifestyle, that appeals to me: sort of slower-paced, hiking, craft beer. I have a lot of friends in that area too.

CL: You talk about exercise a lot and mention making the time to exercise in almost every chapter. How are managing to keep up with this need during this time of social distancing?

EH: We don't quite have the same restrictions here in Whitehorse as people do elsewhere. The gyms are closed, but I am exercising more during the pandemic than usual, because there’s nothing else to do. I walk the dog and I run. And mountain biking season is starting and there are no limitations on any of that, as long as you're careful about social distancing.

CL: What kind of advice do you think you'd have to share with people that are confined in their small city apartments reading your book?

EH: I guess it's about finding a way to do something within the rules in your region. Just about every jurisdiction is allowing walks for mental and physical health. So finding a way to feel safe walking, and thankfully, some cities are getting better about closing streets to create more space for people to walk. A walk or a bike ride within the rules in your area can be so helpful. Jumping jacks on a balcony. Anything that gets your blood moving will feel right.

CL: In a livestream about the book, you mentioned a favourite writer who has had a deep influence on your work. Can you tell me more about her?

EH: Mary Roach. She's a science writer who doesn't put herself in the book in the same really personal ways that I did necessarily. But her books each tackle the science of an area. Bonk is about the science of sex, and Stiff is about the science of death basically, of dead bodies. So she does stuff in that one like going to this body farm where they study decomposition for crime labs. Gulp is about the science of eating, and she uses herself as a guinea pig in all her books, typically throwing herself into experiments or trying things out herself—immersion journalism. So that approach to science journalism was an inspiration for me in Nerve.

CL: Overall, do you think it worked?

EH: I think so, yeah. I knew that the fundamental challenge of the book was always going to be making those two halves work together, the personal and the science. And the big question was: am I going to pull that off? I feel like at a basic level, it does work. I think the extent to which it works for people will vary by individual. You know, some people find the science more interesting and are impatient with the personal. Some people are more interested in the personal storyline and found the science digressions a bit slow. But I think on a basic level, yes.

CL: Do you think the writing helped you be less afraid?

EH: Yeah. Not even the writing necessarily, but the process of doing the book, the research, and the therapy. The whole package of producing this book, having those experiences, doing the research, and then pulling it together in a written format helped me be less afraid, for sure. I was fundamentally different at the end of the process than I was at the start.

Correction: An earlier version of this blog post contained several transcription errors that altered the meaning of the quotes. They have been corrected and Maisonneuve regrets the error.