Maisy's Best Books of 2014

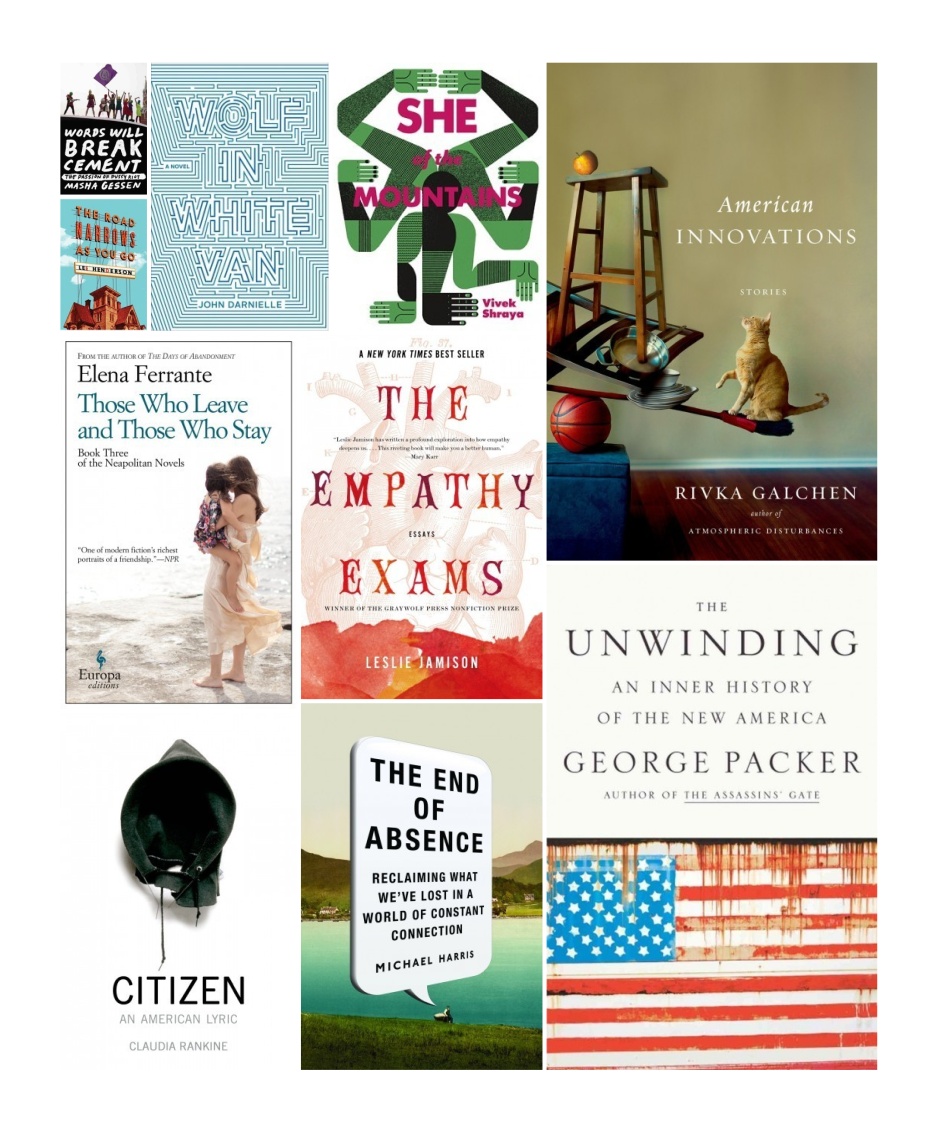

AMERICAN INNOVATIONS (Farrar Straus & Giroux) by Rivka Galchen

One night in June, beneath a Brooklyn ceiling and a Brooklyn lamp with Brooklyn-blistered feet, I read American Innovations. All of it. The night was hot, sirens were wailing and a drunk man yelled on the street, “I’m going to step on your gonorreah!” I read in a sort of fever dream, more alive than usual, it seemed, because the book was good, or New York City was just having that effect on me. I bought it at the Strand, walked it over the Brooklyn Bridge, brought it to the opera and it all felt very sacramental, carrying this book with its surrealist witticisms and secret canonical games all over town before I consumed it later that night. I say secret because this book doesn’t think you’re an idiot. On one level it is very pleasurable to read. On another level, it is pleasurable to read if you get what it’s doing—rewriting canonical short stories of yore from the perspective of female characters. So who was consumed, really? Me or the book? I can’t even remember specific details about it—just an impression of the night, the heat, the total absorption, the relief of finally being allowed to sleep.

I read some other awesome books this year, but none of them kept me up all night, so this one wins. Most short story collections are made for bus rides, and train schedules, and lunch breaks, conveniently compressed for the modern reader. But American Innovations doesn’t let you stop between each story. It’s like reading Gogol or Borges except better. Third breasts, rebellious furniture, phantom string cheese. These are the sorts of things you must expect to encounter if you enter Galchen’s world. The sleep deprivation is worth it.

—Shannon Tien reviewed Emily St. John Mandel's Station Eleven in Issue 53.

CITIZEN: AN AMERICAN LYRIC (Graywolf Press) by Claudia Rankine

When Claudia Rankine asks, "What feels more than feeling?" I shrug—not out of indifference but out of a realization that I could never know the answers to the questions she raises. And although this book made me think more than it made me feel, here are several thinking/feeling questions that struck me in this hybrid-poetry-essay-thing: What does it mean that this book "about racism" feels trendy? Wait, what does it mean that racism feels trendy? Perhaps I've lived in New York City too long (only two years), where "black lives matter" falls off the tongue like a piece of gum spat on the pavement and I can't march on that pavement without being surrounded by white people.

If I ignore all that, the very idea of something like black experimental writing emerges as another question with no answer. Citizen feels bracketed by sighs. I'm in it. Rankine describes situations I've told no one about. She describes rage I've twisted into a mere non-smile. Composure, she calls it. I call Citizen not quite poems. The book contains images by Glenn Ligon, Wangechi Mutu Carrie Mae Weems and others, and in that way, it reminds me of another breathtaking poetry book slash art piece, Bough Down by Karen Green. All year I've been reluctantly obsessed with so-called reading practice and so I'm forced to wonder how to even read Citizen: An American Lyric. Although the title might announce something like a genre, I can't theorize how to read a something that states "context is not meaning."

While Citizen, with its decapitated hooded cover (the cover art is In the Hood by David Hammons), might seem almost too damn current, the historicity of blackness singes my tongue and then cuts it off and I gag. I gag on an all-day nineties-themed television marathon and I wonder where these people were when Tupac died. By its title, Citizen addresses a public but I yearn to keep its pages all to myself.

—Tiana Reid wrote about the myth of Canadian multiculturalism in Issue 52.

THE EMPATHY EXAMS (Graywolf Press) by Leslie Jamison

Advance praise often results in a disappointing read, especially when a book gets as much anticipatory acclaim as this one did. I picked up The Empathy Exams with dangerously high expectations, and it’s still my favourite book of 2014. Leslie Jamison approaches issues of pain with the language of a poet and a methodology that’s almost scientific. The book’s eleven essays explore issues as far-ranging as coal mining, psychosomatic skin diseases and reality TV through several layers of interpretation: she writes about the ways in which people suffer, how that pain is seen by others, how best to try to understand it, how to think about—and to write about—that understanding.

Each essay is powerful, even when the connections between them seem somewhat vague, but several are truly exquisite. (I particularly loved “Grand Unified Theory of Female Pain,” “Morphology of the Hit,” and “The Empathy Exams.”) Jamison writes with incredible precision of language, and consistently makes resonant insights. The titular essay, one of my favourite pieces of writing ever, reflects on the strangeness of the relationship between doctors and their patients. Jamison approaches it both through her experience as a medical actor faking symptoms to test med students, and through her own painful surgical history. It’s gorgeous and incisive from start to finish, and it’s available for free on the Believer’s website. Read it.

—Maija Kappler wrote about Game of Thrones, Downton Abbey and Girls for maisonneuve.org.

THE END OF ABSENCE (HarperCollins) by Michael Harris

What have we humans lost in the digital age? This is the deceptively simple question at the heart of Michael Harris’ The End of Absence. For some— I’m speaking here to the proselytizers of everything Google, the feverish adopters of new apps and iPhone models—this question is reason enough to never read this book. But here’s why you should: The End of Absence is the first book I’ve read about technology that is written beautifully.

Using a mix of personal anecdotes and wide-ranging research, Harris tours the digital world and assesses its impact on childhood, love, education, etiquette, attention and memory. The result is a warm-blooded meditation on what it means to be the human multi-tasking between tabs and screens. Harris addresses that unsettled feeling many of us get from a busload of school children silently immersed in their phones, from a friend who interrupts a punchline to answer a text, from the realization that the day has passed by and the computer screen feels burned into our eyeballs.

This might sound like the work of a nostalgic worrier, but Harris’ conclusion is not all gloom and doom. There’s no way to hold back the technological tide that has altered nearly every life on the planet and he knows that. Instead Harris makes a reasoned plea for absence in a world of constant connection and entertainment. You just might discover (or re-discover) a use for boredom and loneliness.

— Laura Trethewey's essay "Collective Independents" appears in Issue 54.

ENDARKENMENT (Wesleyan) by Arkadii Dragomoshchenko

A listing like this is the description of an accident—a reader intersecting with a book at the moment when he or she happens to be receptive to it. It is highly unlikely, so very unlikely, for a book to appear as my favourite of the year, since I encountered so few of the thousands of books published during 2014 (and I actively look for new work). Some of my favourite novels I was involved in editing at BookThug, so I feel that I can’t mention them here (but still, of course, look them up).

The novel whose weight I’ve felt most present was actually first published in 1971 but reissued in 2014 by Dzanc Books: Joseph McElroy’s novel Ancient History: A Paraphase, long out of print, possibly his best—but this does not count as 2014, even with its new intro by Jonathan Lethem.

None of the above take away from the one I will forward, a book I accidented upon by scrolling through Facebook one day—I can’t recall who mentioned it, though surely someone associated with the Summer Literary Seminars St. Petersburg program: the selected poems of Arkadii Dragomoshchenko published under the title Endarkenment (Wesleyan). A handful of Dragomoshchenko’s books have been previously translated into English; this new collection spans the years 1990 to 2009. The writing seems to be the residue of the poet’s warm and desirous sensorium, his restless memory, his interrogations of language. In terms of what they do, what he did, I feel as though his poems are best described by a line from Deleuze: “We write only at the frontiers of our knowledge, at the border which separates our knowledge from our ignorance and transforms the one into the other.” This is the irreducible and essaying territory of Dragomoshchenko’s writing.

Dragomoshchenko died unexpectedly in 2012, as this collection was being prepared for print. I recommend we read his work.

—Malcolm Sutton's short story "Opportunities and Profits in the Coming Great Depression" appeared in Issues 51 and 52.

THE ROAD NARROWS AS YOU GO (Hamish Hamilton Canada) by Lee Henderson

Canadian artists can't help but produce in relation to America. Even those most scornful of American culture remain aware of their scorn, which comes to circumscribe their field of vision. But like every strong rejection, the consciously anti-American cultural product speaks to a deep, unsettling urge toward acceptance, even assimilation. One would be hard-pressed to find a Canadian artist who doesn't harbour an American success fantasy like a family secret. The Road Narrows as You Go, Lee Henderson's ambitious, long-awaited follow-up to The Man Game, asks what happens when a Canadian artist flies toward, rather than away from, that fantasy.

In this modern Peter Pan myth, Wendy Ashbubble, an underground cartoonist from Victoria, British Columbia, runs off to the Neverland of San Francisco in the Reagan '80s, where she becomes rich and famous in grand American fashion. We watch her creations surface in the imagination, only to float free over Manhattan as balloons in the Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade. In Henderson's America, a voracious commercial apparatus of junk bond salesmen, gallerists and agents surrounds the introverted art of cartooning. Artists both real and invented wander through these pages in a haze of weed smoke, as Henderson charts the consequences—aesthetic, ethical, political and personal—of Ashbubble's Faustian pact with America. In many ways, Henderson's novel enacts the ambitions of its protagonist. Set in an American city, with mostly American characters and recognizably American concerns, The Road Narrows as You Go playfully pursues the Great White Whale of crossover success. Of all the Canadian novels I read this year, Henderson's is the boldest and strangest and, facing into the American fantasy with neither transfixion nor disgust, by far the most honest.

—Michael LaPointe reviewed Stephen Harper's A Great Game in Issue 52.

SHE OF THE MOUNTAINS (Arsenal Pulp) by Vivek Shraya

When it comes to Canada’s literary landscape, well-written and relatable queer love stories are few and far between. But for the past five years, Vivek Shraya’s writings have always made for a refreshing read. She of the Mountains, Shraya’s latest illustrated novel, is no exception. The story details the unfamiliar start and eventual crash of a romance between two unnamed lovers, paralleling their relationship with re-imagined tales of mythical Hindu gods and goddesses.

In an often white-washed, heteronormative literary world, Shraya’s story ticks all of the overlooked boxes: It showcases the limits of labelling sexuality, bisexual erasure, the perils of being a queer person of colour in a conservative city and the complexity of religion and gay culture. In its entirety, She of the Mountains is the classic love story that “Others”—those who exist outside the white, straight romantic binary—have long awaited.

—Erica Lenti's piece about men in Women's and Gender Studies appeared in Issue 53.

THE TELLING ROOM (Random House) by Michael Paterniti

I found Mike Paterniti's latest book in the "cheese-making" section of the Whitehorse Public Library—the first time I'd ventured into that particular corner of the Dewey Decimal System. The story begins with Paterniti as a young creative writing graduate, working at a fancy deli and hearing about a sublime and unforgettable piece of very expensive Spanish cheese. Fast forward a decade or so, and he's a successful magazine writer, still thinking about that cheese. In Spain on assignment, he finally gets his chance and takes a detour to Guzman, the small Castilian town where the cheese was made, only to be plunged into a complex story about how the cheese is gone, stolen from its maker at the peak of its success.

From there, Paterniti is drawn into the life of Guzman. He makes friends, not just with the cheese-maker, Ambrosio, but with other village residents. Eventually he moves there for a stint, along with his wife and children. As years pass—the book was eight years in the making—and deadlines blow by, he tries to unravel the story of Ambrosio and his stolen cheese.

But The Telling Room isn't really about cheese. It's about stories, and how we tell them: how Ambrosio tells his story, and how Paterniti, as both a journalist and a friend, navigates Ambrosio's story and the stories told by others. It's complicated and thoughtful, totally gripping and beautifully written. I could be wrong, but somehow I doubt I'll ever say that about another title filed under "cheese-making."

—Eva Holland wrote about the forgotten internment on the Aleuts in Issue 52.

THOSE WHO LEAVE AND THOSE WHO STAY (Neopolitan Novels) by Elena Ferrante

I just want to recommend, in general, the novels of Italian writer Elena Ferrante, pretty much any of them. One is from earlier this year (Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay), but I want to focus on 2002’s The Days Of Abandonment, which was my introduction to Ferrante’s work, and one of my favorite novels I’ve read this year. I originally learned of Ferrante through Twitter, first by repeatedly seeing mentions of her name, then via someone posting a link to an article discussing her novels in depth. Ferrante, the article told me, wanted to remain anonymous, didn’t do face-to-face interviews and felt that her job was to write books, not promote them, which seemed, to me, like a refreshing philosophy. I often feel, and writers around me often reinforce this worldview, that I should self-promote as much as possible, maintain an active online presence, publish interviews and essays and etc. to put myself “out there,” so Ferrante’s opposite philosophy seemed, in comparison, interesting.

The Days Of Abandonment is both pleasurable and distressing to read. On one hand, Ferrante uses spot-on images and comparisons to capture specific sensations, moods and feelings, which makes her prose memorable and stimulating. On the other, her protagonist spends the majority of the book experiencing an increasingly worrisome downward spiral. The end result is, I think, a very “internal” novel that makes you feel, as you’re reading it, like you’re getting closer to the eye of a tornado. The book starts with the kind of bang a rogue meteor colliding with Earth would make (“One April afternoon, right after lunch, my husband announced that he wanted to leave me.”) and just keeps going from there, rarely losing momentum.

—Guillaume Morrisette called for artistic communities to have open conversations about abuse in his essay "Alt Lit: A Eulogy" on maisoneuve.org

THE UNWINDING: AN INNER HISTORY OF THE NEW AMERICA (Farrar, Strauss and Giroux) by George Packer

An editor acquaintance in the magazine world, someone with whom I have a conversation maybe twice a year, suggested that, since I teach long-form writing and literary journalism and so on at Ryerson University, I ought to read Packer’s latest work. Actually, urged is the appropriate word. The Unwinding (published in hardcover in May of 2013 and in softcover this year), is intended to be a long anecdotal explanation for how the economic, moral and democratic leadership of the United States went awry over the past thirty-five years. She’s right—Packer’s book is worth poring over. The real gob-smacker is its structure. Imagine reading about what ails America and landing in the middle of thumbnail biographies of such disparate figures as writer Raymond Carver, retail monopolist Sam Walton and political joker Newt Gingrich. Cue astonishment in reader’s mind: Please tell me why I’m in the middle of Oprah Winfrey’s bio? Packer sprinkles about a dozen of these six- to eight-page sketches throughout the book. The intention is to show that while a few people still succeed, the system is gamed to its foundations.

Packer also introduces us to no-name folks and cycles back to them over and over again. These are characters whose fate we grow to care about. Dean Price (in seven sections), for instance, represents the guy who is trying to play by the new rules but finds that the house wins every time. Could be corporate America, could be lack of government follow-through, could be good old business enemies, and, indeed, could be Dean Price’s own shortcomings. Tammy Thomas (in six sections) represents Black America trying to survive and raise children in a hostile environment—trying to do, against long odds, what previous generations used to take for granted: make better lives for their kids. And Jeff Connaughton (in seven sections) represents that smart guy who, instead of taking Wall Street’s easy money, went to Washington to work for Joe Biden to make a difference (let’s just say Amtrak Joe doesn’t come off so hot). Packer adds two more elements. One is a series of single-page stingers dedicated to one year, with ticker-tape mentions of various news and culture events separated by ellipses and various typefaces, bolds and italics, e.g., 2012: . . . Young people, selected by lottery, slaughter one another with kill-or-be-killed desperation in “The Hunger Games” . . . WHY DO BILLIONAIRES FEEL VICTIMIZED BY OBAMA? . . . .

The last element has to do with geography, as Packer singles out economic regions, including Wall Street and, in three units, Silicon Valley. Less obviously, Packer scatters a rich five-part portrait of Tampa, ground zero of the housing pyramid scheme, through the book. The cumulative effect of these returning sub-themes is a form of resigned illumination—the only quality growing in America is the ability to scam. On the other hand, you could be another kind of reader. Instead of patiently following Packer’s tarrying path (Oprah Fucking Winfrey? What the . . . ?), you could be a reader like my wife, the kind who flips through and reads the Connaughton sections, then the Thomas sections, etc., in order. But then you might miss the odd section and fail to catch Packer’s teleological drift.

—Bill Reynolds wrote about the 20th anniversary of Kurt Cobain's death in Issue 51.

WOLF IN WHITE VAN (Harper Collins) by John Darnielle

In the past year, I’ve read, re-read, reviewed, skimmed, poked at, or purchased-and-then-just-stacked-in-my-room maybe two dozen books. But apart from a re-read of Pynchon’s Inherent Vice (for work), I think the only novel I finished this year was John Darnielle’s Wolf in White Van. Darnielle is the singer/songwriter for the Mountain Goats, a band I have never listened to, my tastes being more attuned to all the metal bands Darnielle name-drops in interviews. That said, the book came recommended by a bunch of people, and I’d grown too complacent in my grumpy attitude that novels and made-up stories are just trifling baby entertainments and that the only stuff worth reading are books about drones and the Treaty of Versailles and 6,000 word reviews of the movie Let’s Be Cops. So, I bought a copy from the money-stealers at Type Books in Toronto.

Wolf in White Van isn’t some life-changing read or anything. But it ended up being exactly the kind of book I needed to read at exactly the right time. Wolf in White Van is all about the persuasive sway of fiction, and of art more generally: whether pulp Conan novels, heavy metal tapes or richly imagined post-apocalyptic gaming landscapes. Convincingly, Darnielle imagines these escapes as being as freeing as they are toxic—the worlds we immerse ourselves in are sometimes the worlds we lose ourselves in, for better or worse. Just as convincingly, the author concocts a rich, sad, utterly believable psychological geography for his protagonist, like a Dungeon Master laying out all the dungeons and forked paths of human solitude. Sometimes the best cases for stories are the stories themselves.

—John Semley calls HBO's Girls "Millenial Burns-Os" in Issue 54.

WORDS WILL BREAK CEMENT: THE PASSION OF PUSSY RIOT (Riverhead Trade) by Masha Gessen

Masha Gessen is a powerful reporter, and surely one of the bravest working today. Her reporting from inside Russia is critical, nuanced, illuminating and declines to descend into the sensationalist rage of many in the Western press who seem to be eager for a new Cold War.

When members of Pussy Riot were jailed after their famous punk prayer, these proudly feminist and anti-capitalist women were somewhat bizarrely celebrated by politicians in North America who would gasp if they knew their politics. Gessen cuts right to the heart of the matter: what does it mean to tell the truth in a society where the political and public rhetoric is based on lies? The book is part oral history, part anti-Putin polemic, part cultural history and above all a work of incredible reporting. Gessen goes to the prison where Nadezhda Tolokonnikova was jailed, and dives into the history of Moscow's protest-art scene, with extensive interviews with Pussy Riot's members. Should be read by international relations students, sociologists, reporters, punks and prison abolitionists.

—Michael Lee-Murphy's cover story on New Hampshire's anti-hydro line protests appeared in Issue 51.