Illustration by Yarek Waszul.

Illustration by Yarek Waszul.

Now We Here

Canadian society celebrates diversity, but only when it's convenient. On the country's complicated relationship with blackness.

IT USED TO BE that the small crop of celebrities who hailed from Toronto—Christopher Plummer, Jim Carrey, Rachel McAdams, Mike Myers—were mostly white. Last year, that changed. From college basketball stars such as Anthony Bennett, Tristan Thompson and Andrew Wiggins to singers like Abel Tesfaye of the Weeknd and Jahron Anthony Brathwaite (a.k.a. PartyNextDoor), the city often presents a black image to the world.

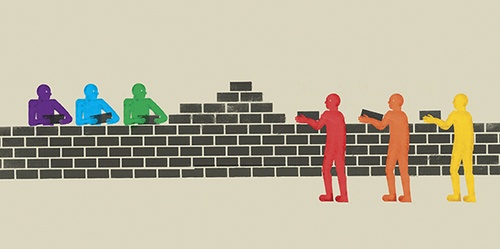

Two figures stood out during the shift: Drake and Rob Ford. Arguably the city’s two most famous citizens, they’re what the world sees when they hear the word “Toronto”—for better or for worse—and both men represent different aspects of the city’s fraught, ambiguous relationship with its black population. In Canada, blackness is at once embraced and held at a distance. Black people have become framed as part of, but simultaneously distinct from, Canada itself.

IN SOME WAYS, Drake is the ideal Toronto posterboy: he self-identifies as black, Jewish and Canadian. He grew up as much at ease in “black culture” (childhood summers in Memphis, Tennessee) as in “white culture” (bar mitzvahs in Toronto’s Forest Hill neighbourhood), to the point of making the distinction seem outdated. Most Torontonians are proud of Drake and not just because he’s the local boy who grew up, made it big and still waves the flag but because he has come to represent our cosmopolitan creed.

Drake also seems like a representative “mixie,” the moniker bestowed upon mixed-race children in a recent issue of Toronto Life magazine. The piece held this blending of cultures up as the future of Canadian cities and the climax of the Canadian multicultural project. Described as “indeterminately ethnic people whom ... you can spot from across a crowded room," according to the piece you can recognize them not only by their beautiful, racially ambiguous looks but also by the way they spend their time. Mixies love steel drum music. They grew up using chopsticks and eating spicy foods. They are what we want to see when we look in the mirror. They are harmonic and successful.

If Drake and the mixies embody our brightest hopes for Canada’s multiracial mosaic, Rob Ford stands for something less uplifting. He’s the Dorian Gray portrait of Toronto: we don’t like how it looks but it reveals something deeply true about the city. All the evidence suggests that Ford is racist. This is a man who allegedly called the mostly black high school football team he coached “just fucking minorities.” And allegedly called a cab driver a “Paki.” And once praised “Orientals” for “work[ing] like dogs.” Newspapers have also reported him using the slurs “wop,” “dago” and “nigger.”

At first blush, this seems to clash with other facts we know about Ford. For one thing, he hangs out with racial minorities. Probably the most famous photograph ever taken of the mayor, released along with news of the “crack video” that made his name around the world, shows Ford, gleeful and glowing, lifting his arms around three black men. The context in which he used the word nigger is also significant: Ford was railing against the firing of Toronto Community Housing Corporation chief Eugene Jones, a black man, and is quoted as saying, “No nigger gets fired in my town.”

Ford is not alone in accepting and even praising black Canadians one second and demeaning them the next. Indeed, what’s fascinating about the development of Canadian multiculturalism is the incorporation of certain aspects of a culture while the rest are left to rot. We praise blackness under certain conditions, especially when it comes to branding or making money, such as Toronto’s Caribana celebrations (most recently reimagined as the Scotiabank Caribbean Carnival Toronto) or Drake’s annual OVO Fest concert, and denigrate it under others. Too often in Canada, people of colour are the sprinkling of “spice” on the “dull dish that is mainstream white culture,” as the African-American feminist bell hooks has written.

Rob Ford personifies this trend to a T. Think of the way he uses Jamaican patois among friends, dropping “chas” and “bumbaclots” in his now-famous video rant at Toronto’s Steak Queen restaurant. See, he’s embracing Caribbean culture! Except he’s not—not in any meaningful way. Or take my alma mater, Oakwood Collegiate, once the proposed site of Toronto’s first “Africentric” high school curriculum in 2011. Critics called the program a form of segregation and quickly shut down the possibility, but I remember students at the school who already chose to enter through specific doors based on their ethnicity. For all the self-congratulation about mixies and mosaics, Toronto can still be starkly divided along racial lines.

As is usually the case, separate means unequal. In Grade Nine, people told me I wouldn’t get into university if I transferred to a place like Oakwood, a school with lots of black students. Toronto’s black student dropout rate has been as high as 40 percent in recent years, about double the city average. (In 2013, an Africentric high school curriculum was introduced at Scarborough's Winston Churchill Collegiate Institute to combat this.) Meanwhile, a recent report compiled by the African Canadian Legal Clinic stated that 40 percent of African-Canadians live below the poverty line as compared to 5 to 10 percent of white Canadians.

Black Canadians didn’t bring this state of affairs on themselves. At various levels of government, and in civil society at large, black people face an unusual degree of prejudice. In a 2012-2013 report, Canada’s Correctional Investigator Howard Sapers said that there has been an 80 percent increase in the black prison population in Canada since 2003. Some of that increase is likely attributable to “carding,” a controversial practice that involves the Toronto and nearby Peel Regional Police disproportionately stopping and collecting information from black and brown men. The Black Action Defense Committee, which has struggled against the violent effects of racial pro- filing for decades, has filed class action lawsuits against both police services. But carding has gotten little coverage in the media compared to the firestorm around New York City's similar stop-and-frisk policy, with which many Canadians are more familiar. The lack of outrage must have something to do with Canada’s discomfort discussing race. “We smoke marijuana on the street, but talk about race in secret,” wrote Jen Sookfong Lee in a piece for Hazlitt magazine titled “The Myth of Multiculturalism.”

MARIE-JOSEPH ANGÉLIQUE is a haunting of the formation of what we have come to call Canada. She was a black slave in eighteenth-century Montreal who attempted escape many times. She was eventually tortured and hanged for burning down the home of her owner and over forty other buildings. Her guilt, however, remains contentious. For many writers and scholars, she is a reminder that black people in Canada are not a twentieth-century invention, and that Canada’s relationship to slavery wasn’t just hitched to the altruism of the Underground Railroad.

Most black Canadians in Toronto, however, are not descendants of Canadian slaves but recent immigrants from the Caribbean and their descendants. Many of these Jamaicans, Antiguans and Barbadians came to Canada in the 1960s and 1970s as part of a liberalized immigration policy. Whereas, writes the Trinidad-born Canadian writer Dionne Brand, “the elasticity of ‘whiteness’” eventually swallowed “Ukrainians, Germans, Scottish newcomers and within a generation cleanse[d] Italians, Portuguese, Eastern Europeans,” black immigrants have been spat out. Brand continues, “Inclusion in or access to Canadian identity, nationality and citizenship (de facto) depended and depends on one’s relationship to this ‘whiteness.’” It makes sense to me that my black Jamaican father, who came to Canada in the late 1970s as a child, moved back years later, claiming that “Canada is a white man’s world.”

That claim might seem to hold less water in 2014, when black Canadians like Drake and Wiggins are at least as famous abroad as Stephen Harper. It’s tempting to think that the more visible we are, the more we’ve made it. But appearances can be deceiving. Black people remain outside of the Canadian polity in many ways. Black bodies are useful to Canada’s and Toronto’s diversity strategy only until they’re not—that is, when it comes to celebratory moments and street festivals but not when it comes to confronting the vexed conditions under which black Canadians continue to live. So let’s put the OVO-branded champagne of multiculti self-congratulation back on ice for a minute. There’s work to do.