Mr. Sue-per-man

Jonathan Lee Riches seems determined to drag every star athlete, dead monarch and inanimate object into court—that’s if the zombies don’t get him first.

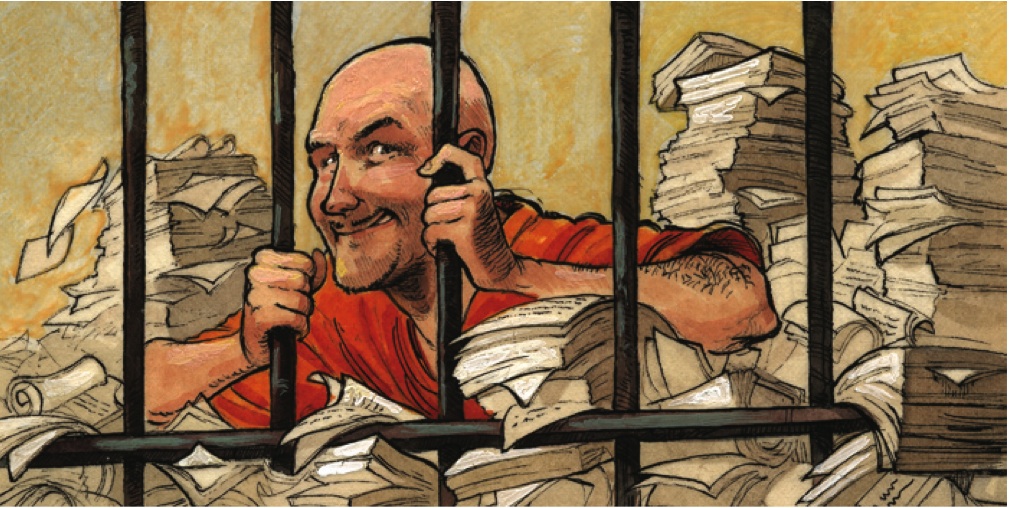

JONATHAN LEE RICHES fights back against alleged wrongs in that quintessentially American way: he files lawsuits. Hundreds and hundreds of lawsuits.

Currently incarcerated in the Federal Medical Center in Lexington, Kentucky, Riches has filed actions against defendants as diverse as disgraced NFL star and convicted dogfighter Michael Vick (for allegedly stealing Riches’ dogs to buy Iranian missiles), former US president George W. Bush (described as “the grand Iman [sic] of voodoo witch doctors turning humans to animals, sometimes plants”) and Barry Bonds (who, along with Hank Aaron’s bat, is accused of treason, skimming the books, illegal electronic wiretapping, and “Batman and Identity Robbin”).

Illustration by Britt Spencer.

Illustration by Britt Spencer.

Dripping with his trademark mix of lunacy and legal savvy, Riches’ suits have been exasperating federal judges since 2006. Some are typewritten, but most are in a characteristic scrawl he claims has turned his right hand arthritic, giving him a numb wrist and crooked fingers. “I eat, sleep and think lawsuits. I flush out more suits than a sewer,” Riches boasted in his latest filing, an injunction to stop Guinness Book of World Records from honouring his hyper-litigousness (Guinness, baffled, denies it ever intended to do so).

Riches’ handwritten grievances are collected in PACER (Public Access to Court Electronic Records), a computer database that tracks every record of every court case that winds its way through American federal courts each year. In the world’s most lawsuit-happy society, that’s a lot of documents—about three hundred million so far, according to Carl Malamud, who heads a group pushing for reforms to the system. Here you’ll find all the dime-a-dozen dust-ups: tractors borrowed and never returned, a cargo of bailing twine damaged by incompetent stevedores, rig workers who cranked their backs and demand compensation, and corporate clashes like the Phoenix Coyotes bankruptcy. But interlarded among these motions, orders, appeals and transcripts are the 2,500 suits perpetrated by the self-described “Duke of lawsuits,” the “Johnny Sue-nami,” the “Patrick Ewing of Suing.”

“Though they are amusing to the average reader,” said US District Judge Gregory Presnell, “they do nothing more than clog the machinery of justice, interfering with the court’s ability to address the needs of the genuinely aggrieved. It is time for them to stop.”

Riches’ talent has clearly been wasted on an unappreciative audience. It’s true he is unbearably litigious, intellectually vacuous and impossible to shut up. But he is also, at thirty-two, an American original. Indeed, the prose in his legal filings is sui generis: a poetic mashup of the technical and the absurd; courtroom officialdom mixed with comic, twisted rantings.

In one suit he claims to have financed English singer-songwriter Amy Winehouse’s career from bank robbery proceeds. “Amy Winehouse told me to be a suicide bomber and attach explosives around my neck,” Riches writes. “So if I get caught robbin’ banks for Winehouse, I won’t be able to implicate her...and I will go to paradise instead with 72 Winehouse virgins.”

He has sued Black History Month, Habitat For Humanity, and, in one famous suit, Bill Gates, Skittles candy, Canada’s Liberal Party and the Magna Carta (along with five pages of additional co-defendants) for conspiring with the Duke of Normandy to pervert the English language.

Riches first gained notoriety in 2003, for his involvement in an identity theft scheme in Holiday, Florida. A teenager in Dallas allegedly phished the credit card details of hapless AOL users and sold them to Riches. Riches lived something of a white trash high-life with the stolen cards, buying Gucci bracelets, gold hoop earrings and a whack of computer equipment before the FBI closed in on him.

Arrested in February 2003 along with seven accomplices, including his parents, Riches entered a plea agreement in September of that year and was sentenced to 125 months in federal prison.

Riches’ earliest encounter with the courts as a litigant is related to the return of confiscated property he allegedly purchased with the stolen cards. After his appeals attorney failed to win back his items, Riches took the law into his own hands with a firm but polite typewritten lawsuit. “I ask this Honorable court for all property returned to me in Exhibit 8,” he said, referring to an Apple laptop, sixty-two gift cards and sixty-six shirts and blouses, still with their tags on. The court, unsurprisingly, refused: “It is hereby ordered that the items, are forfeited to the Federal Bureau of Investigation so that they may be donated to Goodwill Industries.”

Riches went off the rails. The suits henceforth became more bombastic, the demands more outrageous. He asked the court to pry the financial records of the prosecutors behind his conviction, claiming Goodwill bribed them with kickbacks for the donated property.

He also exposed the real motivation behind his “unjust” prosecution: his identity theft put in jeopardy the United States’ Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, which, in an implausible chain reaction, would have collapsed and dragged down the entire executive branch.

The typewriter was taken away. The stamps, too. But with the help of other inmates, he kept filing lawsuits, injecting himself with flair into current events. Apart from his own suits, he has intervened in battles between FedEx and its employees over their work conditions, and masqueraded as several celebrities, including our Conrad Black. (“It is obvious Conrad Black did not bring this frivolous motion,” the judge deftly noted. Apparently the request for ExtenZe Maximum Strength Male Enhancement, Bon Jovi albums and a dill pickle jar didn’t add up.)

Riches also attracted attention from National Public Radio and other media when he sued NFLer Vick and named al-Qaeda as a co-conspirator, demanding “$63,000,000,000.00 billion” backed in gold and silver, to be delivered by UPS to the front gates of the prison.

Justice being blind, the courts are loathe to dismiss lawsuits simply because they look silly. More often, Riches’ suits are dismissed because he has failed to pay the $350 filing fee. In rare cases, judges vent their exasperation.

“Mr. Riches’ motion is not merely spurious, it is outrageous,” said Dennis Inman, a Tennessee judge, when Riches asked to intervene in a case that alleged dairy companies overcharged schools for milk.

“Riches’ numerous and repeated filings,” said Georgia judge William T. Moore, “are substantially and deleteriously straining the Court’s limited resources. In short, something must be done now to curtail this completely unnecessary burden.”

Riches, unperturbed, consistently appeals, but never wins. So far, his suits have effectively been banned from districts in at least five states, but with a country full of federal districts, and the United States’ plethora of state and local courts, he has no shortage of forums.

Why does he do it? Unfortunately, it wasn’t possible to ask Riches himself. Stiff-necked staffers at his Kentucky prison did not allow an interview. Like any prolific author, though, Riches’ own work provides some insights into his character. “I’ve been persecuted to the fullest by judges who are denying me due process,” he said in one suit. “I have a constitutional right to be heard,” he says in most.

“It is not clear whether these outlandish pleadings are products of actual mental illness or simply a hobby akin to short story writing,” Judge Presnell wrote in one court order.

Short answer: hard to say. “This seems to go beyond either psychopathy or paranoia, based on what I read,” said Adelle Forth, a psychology researcher from Carleton University who has studied in several Southern Ontario institutions.

It is difficult to diagnose someone from documents, Forth said. Still, she noted that bonafide psychopaths tend to involve themselves in things that affect them personally—like complaints about the quality of prison mattresses—not pursue grandiloquent claims against fictional entities. “Most offenders don’t engage in this kind of behavior.”

“I would think it’s meeting some sort of psychological need on his part,” she said. “But it could just be that it fills his time.”

There is still time to fill. The federal prison system will spring Riches on March 23, 2012, if all goes according to plan. When freed, Riches knows what he’ll do.

“I’m going to start a lawsuit 101 shop and teach Americans how to file pro se lawsuits. I will sell Jonathan Lee Riches t-shirts, ‘watch what you do or I’ll sue you,’ with my face in the middle pointing,” Riches vows in one suit.

That might not come to pass. In a suit against the Terminator, Sarah Connor and Christian Bale, filed in late May, Riches had a dire warning for us all.

“The Terminator was sent back in time to round me up,” he said. “In March 2012, the day I got released from my illegal prison sentence, I programmed the world to turn into zodiac zombies to feast on one another.”