Confessions of a Teenage Fabulist

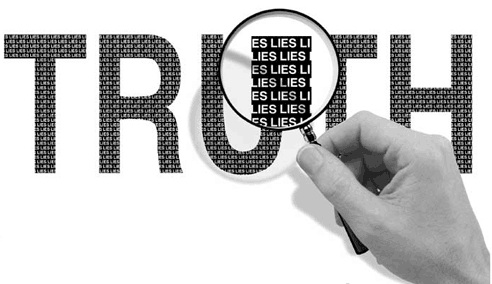

What happens when a scholarship student at a top Canadian journalism school fabricates close to a dozen stories? Nothing, apparently.

THE DAY OF MY FIRST Journalism 101 lecture, I took a seat amid 250 of my fellow students. We were skittish and excited at the start of term. The professor entered the hall and walked slowly to the podium. We were chosen, she said—the best of the best—and we would be entering into one the world’s most socially vital professions. I diligently scribbled down catchphrases like “watchdog function,” and “position of responsibility and integrity.” I was full of piety that morning in that church of the fourth estate.

How is it, then, that within a year I would be fabricating interview subjects, inventing quotations and pretending to bear witness to countless real and imagined events? I have a confession to make: my name is not Kate Jackson and I lied my way through journalism school.

I started fabricating stories at the beginning of my second year. My professor announced that each Friday we would be required to hand in a newsworthy story, which we had to discover, research and write ourselves. I shuddered, and vowed to come up with a cache of fallback story ideas. Class let out, and I tried to head purposefully home to start working but was caught up in the student exodus to the pub. I had a whole week to come up with my first story, I reasoned. One night off wouldn’t hurt.

The following Wednesday, I sat down with my notepad. My three story ideas, so far, were (1) find a local bylaw being passed and discuss its significance; (2) cover Rwanda’s genocide tribunals; and (3) report on President Clinton’s “sexual relations” lawsuit.

Damn. None of these would work. I didn’t have the time or the resources to flesh out any of them. I had to do something. I looked frantically around my room, seeing nothing but laundry, half-read English books and concert flyers. I wanted to go to a show that evening, but I didn’t even have ten words written. It would be a good show, too—a popular local band, “the next big thing”—part of what was being touted as the rejuvenation of the city’s independent music scene... which would actually make a pretty good story. And being there would lend an insider’s perspective. I breathed a tremendous sigh of relief. Journalism could be fun after all!

I woke early Thursday afternoon to a pounding headache and a dearth of viable notes. I had a lot of phone numbers—but from people interested in sharing a bed, not a story. I tried to get some quotes by calling a friend of a friend whose roommate’s brother was in the band. No dice. What was the drummer’s name? Hadn’t I talked to him at some point? I scanned my phone numbers again and wondered if I’d think better after some Advil and a nap. I fell back asleep and dreamed I was standing outside my professor’s office, preparing to hand in my article. Except I was completely naked, trying to cover my body with the blank pages of my assignment as my fellow students surrounded me, pointing, laughing and bearing their teeth. I awoke with a start, white-knuckled and covered in sweat.

With the deadline looming, I tried to think strategically: one mid-sized city’s independent music scene was as good as another’s. I could seek inspiration from what had been written about other scenes and sprinkle it with local flavour: the band’s studied “cool” and the roadies’ placidity; the club owner’s aggrandizing sound bites and the groupies’ effulgent enthusiasm. In short, I could fake it.

I wrote feverishly through the night, trying to get the sound of each interviewee just right. I slid the assignment into my professor’s mailbox the next afternoon and whistled my way out of the building.

In class that week, I was sure everyone was staring at me as we discussed journalistic ethics—how to properly cite sources, the importance of accuracy and the dangers of misrepresentation. With the notorious New York Times fraudster Jayson Blair still an unknown (Blair was studying journalism in Maryland at the time), the professor held up another cautionary tale: Janet Cooke’s inventive story about a child heroin addict and her subsequent fall from grace at the Washington Post. I felt like there was a glowing red F sewn onto my breast: truthful journalism fuels democracy and I had abused a sacred public trust.

I sat perfectly still in seminar that afternoon as our stories were returned. The professor moved through the class, handing back our assignments like some terrible game of Duck, Duck, Fraud. Duck, Duck, Fraud. I stiffened as his feet came my way. My eyes focused on the ground, then on the tassels of his loafers. He put the paper in my waiting, penitent hands and leaned down to murmur in my ear:

“Excellent first piece of work,” he breathed. “A strong use of interviews to highlight how important music is to the city and its economy.”

“Thank you,” I said, feeling suddenly very alive. “It’s easier when you’re passionate about what you’re doing.”

“Quite right,” he replied, and continued his way around the room.

I was inordinately pleased. Professional journalism’s tone and style, the rules of story construction, the criteria of newsworthiness—all these could be fulfilled without leaving my room or interviewing anyone. No need for a thousand monkeys at a thousand typewriters. News isn’t Shakespeare: it practically writes itself. But writing fiction was not why I went into journalism. Next time, I told myself, I would have to go out into the real world and find a real story.

But soon enough, I found myself nervously watching the hockey game at a nearby pub—no story written, no ideas in mind, another deadline hanging over me like a guillotine. Somewhere between the big screen, drunken fans and barroom drone, inspiration struck. I jotted down pieces of the televised post-game interviews and had another beer to celebrate my diligent research. The following week, the professor lauded my willingness to tackle sports stories.

“I’m wondering,” he asked, “how you managed to talk to the players.” Heat flooded my face. I was about to be exposed. Flailing around for a plausible answer, I told him that I had followed the other reporters into the dressing room. “I guess I went with the flow. I didn’t actually ask any questions myself, since I wasn’t really supposed to be there. I just listened to their answers and wrote them down. And tried not to stare as they were getting changed.” The professor laughed. “That’s how these kinds of things usually get covered,” he said. “You’re gutsy. That’s good in this business. I look forward to what you produce next.”

In total, I wrote nearly a dozen fraudulent stories over two semesters, sticking to soft news and human-interest pieces. I often drew upon my social life for inspiration, “covering” local events I attended and imaginatively filling in the blanks instead of doing actual background research. My stories were pithy and concise, just like we’d been taught, earning me the straight-A average required to stay in the program. Each time a fake story was handed back to me with praise, I was both pleased and stunned that I had gotten away with it again. I guess it would have been impossible for one professor to fact-check almost one hundred student stories every week; we were, it seems, working on the honour system.

Of course, it wasn’t meant to be like this. I chose to go to journalism school imagining myself as a rogue and daring reporter, my life a glamorous mix of debauchery and storytelling. The summer before school started, I’d sit behind the pro shop counter of the golf course where I worked and make notes for my inevitable Pulitzer acceptance speech. “People need to know about the realities beyond their own,” I’d pontificate to stunned golfers clutching bags of tees.

Journalism school hadn’t been my only option, mind you. A creative writing program had offered me the chance to wrestle with my muse, though not on scholarship. But, as my parents reminded me, I needed the money that journalism school was offering.

My final and crowning fiction was a compelling chronicle of people waiting at the airport arrivals gate on Valentine’s Day. There was the elderly man waiting to pick up his wife: after a week apart, their first in almost fifty years, all he wanted was to fall asleep beside her again. And there was the young man full of remorse: after a bitter fight, he was waiting for his girlfriend to return from a business trip. I gave him an armful of roses, a sense of renewed commitment and a strong desire to please her—even if it meant feeding her cat. Stephen Glass-like in its depiction of an ordinary day’s extraordinary nuances, I cleverly ended the piece before any of the couples reunited. The professor read it aloud to the class. My peers applauded. I decided to drop out of the journalism program.

My decision was partly practical: this constant creative writing was taking its toll on my other courses. But the other reason—you may find this hard to believe—was principle. I had been passing off lies as authentic news for months, with no repercussions. For me, journalism school and the degree it promised had lost their aura of authority. Creatively appropriating the reporting techniques I’d been taught made me start to reconsider just how trustworthy they really were. I went to the program director, who pleaded with me to reconsider, not wanting to lose a student with such promise. I insisted, and he unhappily signed the paperwork.

Inventing news is remarkably easy. “It’s not a lie, it’s a gift for fiction,” William H. Macy’s character Walt Price says in the film State and Main, when accused of lying to impressionable, trusting country folk. Lying will always be a tempting option for practicing journalists.

I resorted to these fictions out of a desperate laziness, a trait I was surprised to discover in myself. Growing up, I’d only ever told my parents the most typical of teenaged white lies about where I’d been the night before. In high school, I’d worked hard, getting top marks while holding down two part-time jobs. And my work for other university courses was genuine and equally well received. I had never thought of myself as the type to cut corners; when faced with a pile of work, I tended to sigh and put on another pot of coffee. My behaviour in journalism school puzzled even me.

I realized later that I’d never been fully invested in journalism as a career. It sounded prestigious and exciting in the brochure, but once there, I chafed at the tedium of precise detail and impersonal language. I wanted to write to change how people saw their world, but my heart wasn’t in the news.

I would love to say that I’ve been struggling with my guilt ever since—that remorse drove me to drink—but in truth, I am just relieved to have escaped from an environment that put such a high premium on success, that deception and deceit felt like viable options. Does this say more about me or about journalism? I’m still not sure.

My actions may have been appalling, but I’m hardly the first to fake the news. In March 2006, after just three days on the job, Washingtonpost.com blogger Ben Domenech resigned when his fudging of undergraduate news stories was unearthed. Even the New York Times—the Vatican of the free press—never checked to see if their fresh young reporter Jayson Blair had finished his degree. Even Blair’s fellow students claim that evidence of his bad behaviour was already on display for those capable of looking beyond his “extraordinary promise.” How many Jayson Blairs—or Kate Jacksons, for that matter—have you trusted today? I guess you’ll never know.

As the university’s promotional material promised, my experience in journalism has proven useful ever since. Ironically, those two years of practiced fakery eased my transition into film and television studies. I’m still producing under pressure, but couch-bound research is much more appropriate and accepted, and there’s always the safety net of situating my work as a critical interpretation rather than empirical truth.

I often think back to my first day in that Journalism 101 lecture hall. Now that I’ve told my story, will it be held up as a cautionary tale to fresh crops of journalism students? I hope not. Professors should skip my story and just remind students of the words of Harper’s editor emeritus Lewis H. Lapham: “People may expect too much of journalism. Not only do they expect it to be entertaining, they expect it to be true.”

(See the rest of Issue 22, Winter 2006)