Captain Poetry

Does bpNichol's once-revolutionary wordplay have staying power?

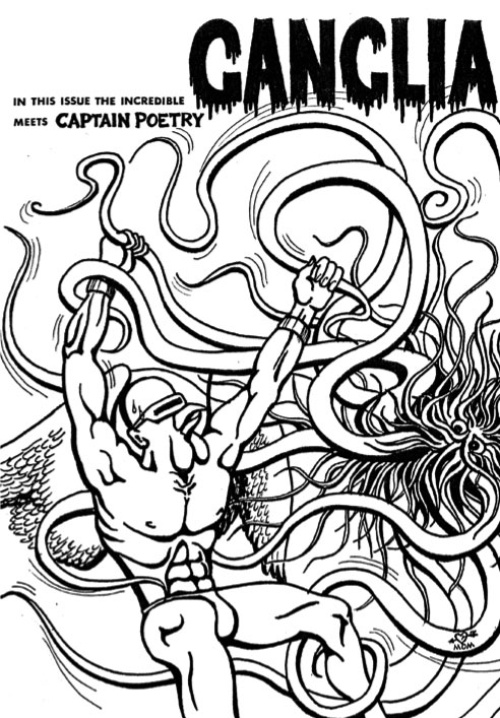

Art by D.J. Nichol.

He dashed off comic books, hatched operas and banged out television scripts. He futzed with fiction, tinkered with radio plays and monkeyed with children’s verse. As a member of the sound-poetry ensemble Four Horsemen, he chanted and nasal-droned for audiences across North America. He favoured collage, comic books, typefaces, puns, doodles and blank pages, and had a soft spot for the letter “H.” Remembered best for the nine-volume The Martyrology, one of the longest long poems in Canadian letters, bpNichol—the beaming, shaggy-haired avant-gardist who died in 1988 at the age of forty-four—became internationally famous for his hand-drawn visual poetry. He called himself a “language researcher.” Mad scientist was more like it.

Alas, Nichol’s super-caffeinated productivity is also, in a sense, hearsay. “Barrie,” writes his close friend Paul Dutton, “could have a few minutes time in an airport departure lounge, or standing at a bus stop, and out would come the notebook and pen.” But much of what he did with that notebook and pen remains scarce, housed in private collections and rare book rooms. A young man in a hurry, Nichol was in love with perishability. “I was interested in the half-life of the poem,” he said in an interview, “the decay, and the fact that things faded away.” Fired up by innovations that allowed him to publish his work when and how he fancied—the mimeograph and the photocopier—he championed the “quick thing”: pamphlets, broadsides, handbills and cards.

These items appeared in limited runs, often editions of one, which Nichol distributed by subscription, sold cheaply or gave away. His ephemera even transcended paper: poems were stitched on pillow cases, printed on matchbooks and—in one pioneering format that dropped straightaway into obsolescence—saved on 5.25-inch floppy disks only bootable on an Apple IIe. Nichol seemed to regard all these try-anything-once odds and ends as a kill switch for good taste. “Instant garbage for the nation’s waste baskets” is how he summed up his publishing activities, a slogan perfectly embodied by an early microbook that instructed readers to promptly burn it. Nichol’s samizdat war against the traditional book resulted in many tactical victories—exciting, unclassifiable confections of word and image—but ended in defeat: a corpus, in Dutton’s words, “unavailable, widely unknown, and far too little appreciated.”

Of course, the challenge of celebrating an artificer whose key artifacts are near-impossible to scare up (or afford: the 1972 silkscreen collection The Adventures of Milt the Morph in Colour will set you back a cool thirty-five hundred) isn’t lost on admirers. Indeed, distress that Nichol will be typecast by his most conservative work sharply divides debate about his legacy, with accusations that the syllabus-friendly The Martyrology—the only book by Nichol still in print—has been used, in Christian Bök’s words, to “sentimentalize his subversiveness.”

In a bid to claw back the diaspora of Nichols’ output, selected poems, prose, comics and essays have been pickled in sundry reprintings and repackagings. These include H in the Heart (1994), bpNichol Comics (2002) and Meanwhile (2002). The best effort is The Alphabet Game (2007), which, by printing his greatest hits alongside “obscure treasures,” serves as a useful periodic table for Nichol’s preposterous range. bpNichol.ca was launched in 2008 as an online lumber room for hard-to-find audio recordings and digitized versions of unobtainable volumes. All of this curatorial activity, however, barely scratches the surface. That’s why, for the last two decades, Ottawa poet jwcurry has been doggedly itemizing every last morsel by Nichol, as well as everything written about him. When completed, the eight-volume Beepliographic Cyclopoedia is estimated to smash the scales at four thousand pages. Nichol would have cherished the irony: the poet who married his creative adrenaline to the demands of fruit-fly publishing, memorialized by a book of such Brobdingnagian proportions.

The Captain Poetry Poems is the latest “lost” work by Nichol to be caught up in the ongoing salvage operation. Originally published by blewointment press in 1971, when Nichol was twenty-six, the booklet was tossed off during one of his most workaholic periods. (He had won the Governor General’s Award for Poetry a year earlier for four books.) A twenty-five-page flood of text, gag panels, thought balloons and hyperbolized letters, The Captain Poetry Poems tells the story of the eponymous superhero and his struggle to find happiness. Bald, beaked and wattled, “Cap”—Nichol’s pet name for him—is hardly the rock-jawed conqueror. In fact, with his visor, spandex, wings and six-pack abs, our man looks like a mutant chicken. Cap is a sad sack: self-conscious, plagued by doubts, undone by indecision, torn about his purpose in life. Nichol shouts encouragements from the sidelines (“O CAPTAIN POETRY SEE IT THRU”) but, plum out of ideas, Cap finds himself in a Groundhog Day funk (“O he sings like a madman, talks like he’s sane, / and does it each day again and again”). And popping up everywhere in the book (in one case even cradling Captain Poetry’s head) is Nichol’s most intriguing and disquieting alter ego: Milt the Morph, the dementedly smiling, empty-eyed troublemaker.

It’s obvious Nichol intended the book to be both a send-up of the poetic tradition and a kiss-off: he writes of Cap, English poetry’s greatest defender, “yur slippers made of paper / yur words made out of milk // yuve seen better days.” The Captain Poetry Poems is a running ledger on whatever the hell occurred to Nichol when writing it; Boy Wonder serving notice of his independence. The iconoclasm of the project inspired Michael Ondaatje to make a short documentary on Nichol, Sons of Captain Poetry, released at the same time. But except for one excerpt reprinted in a few anthologies—an amusing quarrel between love interest Madame X and Captain Poetry (“dear Captain Poetry, / your poetry is trite”)—the chapbook is a largely overlooked slice of Nichol’s fugitive canon. Younger fans may not even know it exists.

Toronto’s BookThug, however, thinks Captain Poetry deserves rediscovery. With the help of Nichol’s friends, the feisty press has assembled a corrected edition, out now, incorporating material missing from the original. Also included is an afterword by blewointment’s then-publisher bill bissett, recreating the midwinter scene as the tiny crew cranked out copies (“zoom inside th cabin n see us printing ovr dayze n nites”). The crying need for a “corrected” version may have something to do with enduring rumours that the blewointment book was so rife with errors that Nichol basically disowned it. (It was the last title from the press to bear Nichol’s name.) Forty years later, BookThug is waving under our noses the edition Nichol would have approved.

An excellent case can be made for considering the reissued Captain Poetry Poems more historically significant than the dozens of similarly totemic keepsakes still waiting to be rescued (even if, as the editors warn, it “may not be the ‘best’ work in Nichol’s oeuvre”). This is largely due to the addition of a never-published prose coda by Nichol (“some words on all these words”) that drops two surprises. First, he proposes that Captain Poetry is one of the missing links to The Martyrology. (For Nicholites, this is akin to unearthing the papyrus napkin where Sophocles jotted down the idea for Oedipus Rex.) Second, and more striking, is Nichol’s claim that Captain Poetry was created to satirize stereotypes rampant in Canadian poetry during the 1970s: namely “the macho male bullshit tradition,” as he puts it, “where if you were male & wrote poems you had to make damn sure you could piss longer, shout harder.”

No doubt Nichol had in mind poets like Patrick Lane, Al Purdy and Irving Layton, all of whom incorporated the “piss longer, shout harder” swagger into their debates about poetry. Nichol, however, never bought the Hobbesian vision of a literary scene. This was the entire point of the “gift economy” he is so often associated with. Through zines like Ganglia and grOnk, Nichol tirelessly promoted and published a vast range of work by those he admired, and did so without expectation of quid pro quo. Fame just wasn’t a going concern for him. “Behind Ganglia and grOnk,” Nichol said in an interview, “was a strong idea: to focus on certain work, to argue for that work, and to put enough of the work forward so that readers could get a feeling for the sheer quantity of people who approached the text in this way.”

Nichol was thus both a tastemaker and community-builder. His own example—most notably through the beguiling manifestos he and Steve McCaffery collaboratively wrote and circulated through the Toronto Research Group—helped turn Toronto’s small-press scene into a large ensemble act, spawning cooperative projects free of us-and-them demonizing or the sizing-up and dressing-down of peers. A practising psychotherapist (for years he belonged to the talking-cure commune Therafields), Nichol lived as though he were barely able to hold back some vast exuberance, and it gave everything he did an extra positive charge. More importantly, he had a knack for schemes that made a virtue out of this very insouciant unseriousness. He helped rewrite the rules for his generation, not only by offering those around him a new set of permissions, but by handing them an unexpected challenge: to give their experiments the direct evidence of human touch.

That’s why, when a publisher reissuing a book like The Captain Poetry Poems explains that “all efforts were made to present the material in the spirit of the original,” a caveat is required: the “spirit of the original” is rooted entirely in its material. The new edition keeps the comic book size, but everything else is upgraded, tidied up, made reader-friendly. Lost is the on-the-fly quality of its original appearance. As was Nichol’s wont, the book’s design—mimeo sheets stapled along the top edge—was employed as a counter-agent to the squareness and predictability of the “big-presses.” He practiced a warts-and-all avant-gardism, and as such the original Captain Poetry Poems got its revolutionary mystique from the way it conspired against itself. It seemed aware of its own forgettable fate, even relished it. (Run across a copy today, and it will be yellowed and foxed, its decay a poetic device against timelessness.) Captain Poetry was part of Nichol’s ongoing attempt to free poetry by killing it and resurrecting it as junk art. At the time he published The Captain Poetry Poems, he was on a creative spree, spending big on what no doubt appeared to be triflings. “They’d pick it up,” Nichol said of one of his early books, “and they’d see there are three words to a page and kind of flip, flip, flip, and they’d be through it in 30 seconds and say, ‘What the fuck was that?’” But those works gave many younger Canadian poets their Keatsian “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer” moment. It was literary gunpowder and blew their minds.

Nichol’s most interesting work is premised on a simple idea: poems are made up of combinations of words, which are made up of combinations of letters. This allowed him to break down lexical identity in ways meant to remind readers that every word is one letter away from every other word. Sometimes he did this by taking words apart in the course of the writing. We see this a lot in The Captain Poetry Poems: “up the creek / the cup reek / EEK!!” Language was basically sonic Lego that could be recombinated into original typescapes. In one early example, printed on a postcard, “turnips are” becomes “rustpin,” “stunrip,” “puntsir” and “tipruns.” Another postcard explores the interlocking possibilities of “owl,” “low” and “cow.” Nichol’s most extreme manifestation of this idea was homophonic translation, in which he translates the sounds of a foreign language rather than its sense (“c’est l’hommage dansant” becomes, for instance, “sailor magic danse on”). More than a poet, Nichol was a problemist. He created calligraphic conundrums meant to provide readers with “as many entrances and exits as possible.” His word for this was “borderblur,” which he defined as that sweet spot where “language &/or the image blur into the inbetween & become concrete objects.”

He began to think this way in the late 1960s, emboldened by the example of “concrete poetry,” a growing international movement that exalted language’s typographical medium as its one true message. Words were “concrete” material that could be spatially shaped. Concrete caught on with no real sense of what the rules were, making it hard to pin down a definition of what the new genre covered. This suited its practitioners to a tee. Indeed, concrete’s “assault on the decorum of the printed page,” to use Stephen Scobie’s words, was something Nichol grasped intuitively. Increasingly disappointed with the traditional lyric poetry he was writing at the time, he seized on concrete’s major principle—the poem as pictorial rhetoric—with the glee of a boy given access to a secret identity and magical powers. It was the birth of a new kind of Captain Poetry.

Visual poetry gave the idea-a-minute poet a way to stuff his thoughts into nutshells without getting bored. Nichol wanted to say as much as possible with as little as possible, and concrete poetry, by identifying the minimum visual properties necessary, allowed for the sly surfacing of subtext (in one lovely example, Nichol replaced the letter “o” in “cloud” with the billowing of parentheses). Best of all, the form was something he could do to please himself. It was still high stakes—concrete, after all, was bred by crisis, as a challenge to lazy values—but there was no right or wrong. Nichol tracked truth by sight, stalked surprise in the white space of the page. In the best examples (like the affable and awesome “Allegory Series”), you feel him feeding his excitement into his shapes and images. Whether typeset, typewritten or hand-drawn, it’s impossible to ignore the intelligence his best visual poems radiate.

At their worst, though, Nichol’s visual poems are just the wish-fulfillment of a poet who liked the look of his own irreverence. They bespeak an exaggerated confrontation with convention. Nichol was interested in short-circuiting reading habits unchanged since the Gutenberg revolution, but too often, the results merely project his interest. This is why Nichol’s visual poems leave many readers cold. Staged cleanly in open space, they give him away not as a hot-blooded rebel but a Spock-like formalist. Calibrated to convey the sonic weight and density of language untamed by sentences, the poems are full of causeless, do-nothing effects.

Let’s take one example from The Captain Poetry Poems. On page sixteen we have three A’s, two upper case and one lower, overlapping in a trippy Escher-like pattern. Embedded inside—as if readers were stealing a rare look into the soul of the letter itself—is a rolling landscape with a cloud-filled sky and, peeking out of the corner, Morph the Milt. The message is obvious: each letter is a rabbit hole into its own world. Still, Nichol has simply produced the stylized idea of a rabbit hole. How can you possibly respond? True, it has a quirky vigour that tells us an actual hand drew it. But it’s a typographical bagatelle planted foursquare on a page.

This complaint can be extended to visual poetry in general. Self-enclosed, emotionally static and cut off from public life, these optical mannerisms are the closest contemporary poetry gets to the automata vision of nineteenth-century craftsmen. In one of his most celebrated books, ABC: The Aleph Beth Book, Nichol uses a stencil to “overlay” each letter of the alphabet into multiple-exposure versions of itself. The twenty-six “glyphs” are like mechanical toys or whirligigs. They amaze at first sight, but deaden in the gaze. They look better the less you expect of them.

Twenty-five years after his death, the same might be said of Nichol. He still means a lot to many poets, but he matters less. The proper historical setting for his achievements was in the late sixties; he came of age in a period in Canadian literature when there was widespread sympathy for oddity, and experimental poetry was the marquee event. As a scene, however, we have drifted several parsecs away from that. The indie lit subculture has shed its prepublication stage of adolescent rebellion. Post-Nichol, the Canadian avant-garde has become warier of grassroots movements, and is now more professionalized, its sense of self more academically located. Additionally, today’s experimentalism no longer has the same power relationship with its audience. Thirty years ago, the avant-garde took advantage of what economists call “information asymmetry”: its poets knew much more about the game they were playing than their readers. Today we suffer fools less gladly. Our bullshit detectors are better, and keeping people interested in convention-flouting is hard work. Nichol’s poetry has fallen short of a crucial threshold: the new that stays news.

Those who flip through The Captain Poetry Poems and wonder what it all means will never know. You had to be there. Indeed, The Captain Poetry Poems only underscores that the long aftermath of Nichol’s death has become a love affair with holy relics. The work may wear badly, but the legend is imperishable. Yet The Captain Poetry Poems also demonstrates everything worthwhile about Nichol: his free-agent sensibility, his bemused distance from the mainstream-verse universe and its “umpteenth poem on me and mom,” his belief that joy could infiltrate poetic conventions and eat away at their genetic structure.

In photographs, Nichol’s smile has a rapscallion edge. He mastered every encounter, be it on the page or in person, with charm. The result was an all-in creativity that never curdled into what Daisy Fried once called “evilly subversive.” What made Nichol’s work so head-turning was that it was a free and unembarrassed expression of art as play. He fulfilled Baudelaire’s definition of the artist as an adult who can “recall childhood at will.” In turn, it allowed him to see with astonishing depth into the fantasy life of children (he wrote for a number of children’s shows, including Fraggle Rock). His many winning moments—his “Pataphysical Hardware Store” catalogue included a pencil with erasers at both ends and inflatable thought balloons that could be taped to someone’s head—point out the most galling failure of our current crop of experimental phenoms: humourlessness. For all his épater ethic, Nichol was too much fun to dislike. Making the individual uncomfortable—Nietzsche’s ambition—wasn’t Nichol’s thing. He was that rare bird: an avant-gardist without an axe to grind. He was seditious, anarchic, optimistic. You kind of miss the guy.

See the rest of Issue 39 (Spring 2011).

Subscribe to Maisonneuve today.

Related on maisonneuve.org:

—On Starnino's Nichol

—The Poetry Scene's Insidious Manlove: A Case Study

—Interview With David McGimpsey

Follow Maisonneuve on Twitter — Like Maisonneuve on Facebook