Old Masters

Poverty is crippling some of Canada’s most productive artists: the elderly.

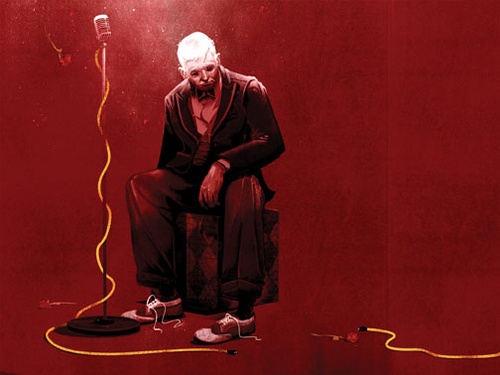

Illustration by Jonathan Bartlett.

Ten years ago, Pat Patterson was a busy stage and television actor. He averaged an audition a week, got eight or nine gigs a year and netted about $20,000 annually—“a decent wage,” as he puts it. Patterson even quit the part-time jobs—working nights as a security guard, driving a Purolator truck—he’d once needed to supplement his income. But when he turned sixty-five, “all of a sudden the work started to fall off,” he says. “One year you’re making $20,000, then the next year you make $8,000, and the next year you make $4,000. Almost as if somebody had turned off a tap.”

These days, Patterson spends his time taking care of his house; he and his wife, another out-of-work actor, struggle to get by on government pensions. Patterson, his voice heavy, calls it “forced retirement.” After all, he says, “you don’t see grey-haired people on television anymore.”

Patterson’s story is a common one. So common, in fact, that in 2006 a group of Canadian arts organizations formed the Senior Artists’ Research Project to study the situation and needs of aging artists in Canada. The resulting report, released this winter, paints a worrisome portrait.

Most artists, no matter their age, struggle to stay afloat. According to the 2006 census, the average artist in Canada makes $22,700 a year, which places many of them below Statistics Canada’s low-income cut-offs. Forty-three percent of artists make less than $10,000 a year, well under the $38,400 that the average working Canadian man earns. (Working women average about $6,000 less.)

Canada’s older artists are hit even harder than the rest. A Canadian artist over fifty-five earns, on average, 38 percent less than an artist who is ten years younger. And according to SARP findings, nearly half of artists over fifty-five have health care needs not covered by public plans. “Canada’s senior artists are experiencing serious challenges in health and isolation, financial insecurity and a lack of adequate housing,” says Joysanne Sidimus, SARP project director and a member of the National Ballet of Canada’s artistic staff.

Such struggles run counter to social expectations. Imagine the typical “starving artist,” and a young bohemian comes to mind, not a grandparent. Imagine a successful older artist, on the other hand, and you come up with someone like Michael Ondaatje: silver-haired and well-dressed, with myriad books, an Oscar-winning adaptation of one of his novels and a renowned literary journal to his name. But in reality, older artists face countless barriers that make it harder for them to work—and, by extension, to make money.

For visual artists like Lillian Loponen, their bodies can be the biggest obstacle. Loponen, a painter based in Whitehorse, hasn’t struggled to sell her work as she’s gotten older, but her energy to produce it has dwindled. “In the past I could work on a project for sixteen hours straight,” she explains. When that became unsustainable, she began to work in eight-hour segments. “But then I found eight hours was a little bit trying, and then I said six hours. [Aging] cuts down on your time, your straight art time.”

While most visual artists and writers may not experience discrimination based on age, older dancers and actors are at a major disadvantage. Actor Pam Hyatt doesn’t hesitate to say she’s faced ageism over the course of her career. “In theatre, do they show old women in major roles? No.”

Granting bodies sometimes exacerbate the problem. Sidimus notes that many government agencies and private foundations run programs specifically for “emerging artists,” with funding set aside for those in the early stages of their careers. Such programs assume that new talents need a boost to get their careers off the ground—and they do. However, Sidimus notes, “if you’re talking about artists over sixty-five, there’s very little in the funding panorama for them.”

Canada’s senior artists aren’t alone in their plight, but we’re lagging far behind countries like Germany, where the partially state-sponsored Artists’ Social Fund provides artist-specific pensions and insurance. In Canada and the United States, on the other hand, trade unions and cultural organizations struggle to make up for the lack of government services. Many actors, for example, describe their dependence on the Alliance of Canadian Cinema, Television and Radio Artists Fraternal Benefit Society, an insurance program for members that provides additional, artist-centred health coverage; it often covers alternative treatments, like physiotherapy, that standard government health care does not. (There are no equivalent insurance programs for other kinds of artists.)

Establishing a state-sponsored pension plan for artists would ease the community’s financial difficulties, but it’s a politically unpopular suggestion. SARP’s project was actually denied certain government grants because, as the report states, “one of the goals of the research was to determine possible levels of pensions to be given to artists. It was later discovered that this goal was not acceptable to government and precipitated the rejection of the application.” SARP eventually removed references to artist-specific pension programs from its grant application. “I think we absolutely should be advocating for programs that will include some form of pension,” Sidimus says, “but, being realistic, I know that goal is down the road.”

Many artists also support paying taxes based on the mean of several years’ earnings, rather than just one—an idea called income tax averaging. This would more closely reflect the self-employed artist’s professional life, as she will often work for several years on a book, exhibition or play that, once finished, provides support for the next few years of creative work. Income averaging would help to insulate artists from the “financial extremes,” as the painter Loponen puts it, that they now face.

“The reality is that for those who are members of unions and have [Retirement Savings Plans], by the time they hit sixty-five, most of them have depleted that RSP because they had to pull it out to pay taxes, or just to live,” says Sidimus. She has sat on federal and provincial Status of the Artist committees, which have proposed income averaging numerous times. The idea, she says, is consistently “stonewalled” by the government. (This taxation system was once available to Canadian farmers, but has since been eliminated.)

As it stands, artists are subject to “the extreme stress of wondering where the next dollar is going to come from,” says Loponen. “Every three or four years, I’ll have a couple of mural projects that carry me through a year or two, and then it hits rock bottom—up to the point where you’re suddenly panicking because you don’t have fuel for the winter. I think quite a lot of students are probably familiar with this [way of life], and here I am doing it backwards. I’m doing it as I’m aging.”

In the summer of 2009, as part of its research process, SARP held town hall meetings across Canada, where artists over fifty-five could publicly discuss the issues they faced. At the English-language meeting in Montreal, about twenty people shuffled shyly into a downtown conference room. The dialogue began slowly at first, but quickly became more animated as the participants began to introduce themselves and talk avidly about their lives.

Amid conversations about housing and financial planning, the attendees found another common thread: while most of them were struggling to find work and get grants, they also said they were at the peak of their careers, ready to take new risks. Other older artists feel the same way. Pam Hyatt, the actor, finally put together a one-woman show last fall, something she’d long talked about doing but had never prioritized. “It was a breakthrough,” she says.

“For me, one of the most poignant aspects of the results of the survey was [respondents’] incredible desire to keep doing what they do—be it creative work, be it performing work—and to share this with other people,” says Sidimus. “If you sat in on any of the focus groups across the country, you would find that most artists who are well enough want to be productive, and they will do so even if they’re in financial trouble.”

Indeed, SARP found that, if given the chance to start over, 87 percent of artists surveyed would still choose an artistic career. Which, Sidimus says, brings us back to oft-repeated questions: “Who is the artist in contemporary Canadian society? How do we value our artists? How do we value all seniors and the knowledge and wisdom they have?”

With that aim, SARP recently founded a new organization to support artists over fifty-five, and is trying to start a program that provides income for older artists who mentor their younger colleagues. It’s a start. As Canada’s older artists are burdened by financial pressure and forced to take on other jobs to support themselves, we risk losing generational wisdom—a kind of artistic institutional memory. “I want to see the arts elevated into something that’s important in Canada,” says Claudio Masciulli, a veteran actor. “[We should] treasure those artists who have endured a difficult life—not only for themselves, but to bring something to society.”

Originally published in March 2011. See the rest of Issue 49 (Spring 2011).

Subscribe to Maisonneuve today.

Related on maisonneuve.org:

—Captain Poetry

—Will Steep Fines Kill the Plateau's Nightlife?

—Writing Her Off

Follow Maisonneuve on Twitter — Like Maisonneuve on Facebook