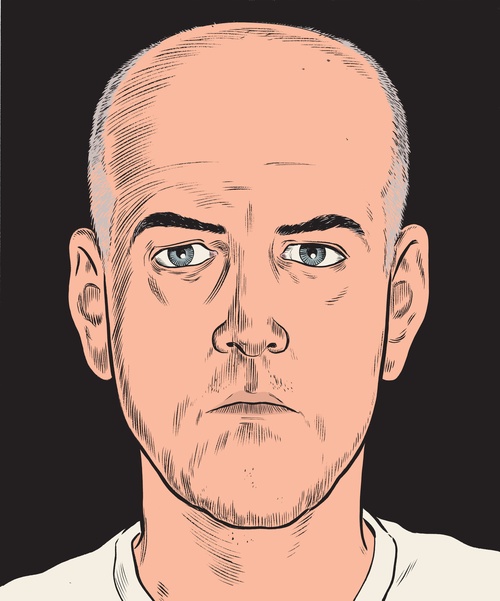

Web Exclusive: Interview with Daniel Clowes

The cartoonist on his new book, The Death-Ray, and getting in touch with his inner sixteen-year-old.

Daniel Clowes has come a long way since the "sweaty, frustrating" comic conventions of his youth. These days, he is not just known for his comics, but for his graphic novels—a term he finds "really imprecise" and "pretentious."

Now fifty years old and living near San Francisco, the wry cartoonist, best-known for books such as Ghost World and long-running series Eightball, has ressurected an unfinished story from his youth. The Death-Ray is a realistic superhero story set in a 1970s American suburb, in which a young orphan discovers he has incredible powers after—what else?—smoking his first cigarette. The book was originally published in 2004 as a softcover comic, selling out immediately. This October, Drawn & Quarterly will release a new hardcover version.

Despite its apparent success, Clowes maintains that the book's plot "is pretty much the worst idea anyone can have." Between calling the plumber and planning his upcoming vacation, Clowes found some time to chat with Maisonneuve about The Death-Ray, screenplays and why the word "movies" is an insult to the English language.

Tristan LaPointe: How did you get started on The Death-Ray?

Daniel Clowes: I had just finished a book called Ice Haven and I was looking for something new to do. The whole idea with Ice Haven was to do something very simple, and it turned into something very complicated. So I was kind of redoubling my efforts to do something simple again.

I tried to think back [and ask myself], "Whats the dumbest possible thing you could do? Like, what's the worst idea to ever pursue in comics?" And that's always to try to do a realistic superhero story. Whenever anybody tells me they're doing something like that, I think, "You should just shoot yourself! That is the worst idea ever!"

So I took that as a starting point: take the worst possible idea and try to do the best job with it I can. I started to think about it, and I remembered this story that I had written when I was sixteen that I had intended to turn into a big graphic novel before the term even existed. As with everything back then, I drew the cover like fifty times but gave up because I never got it right. It sort of stuck with me. It had this sort of emotional power that only something you think of when you're sixteen can—like, "It's me against the world." It resonated in the sort of way. So I tried to sort of go into that lost emotion, and try to recapture it for the story.

TL: But you can't have still thought it was the worst idea when you wrote it.

DC: Well, I still sort of thought that the general notion of doing a realistic superhero comic was basically always a dumb idea, but dumb ideas often lead to good things for me. So I decided to go with it.You have to go with what you feel energized about. All of a sudden, I had a lot of drive to do this story. And once you get that, you have to stick with it—you can't just walk away from it.

TL: Were you worried about the book being even superficially related to superheroes—especially considering how many semi-obscure superheroes have been dragged out [for film adaptations] in the past ten years?

DC: You know, I just don't follow that stuff. There's nothing in the world more boring to me than all that stuff. I've never seen any of those movies, and I just lost interest in all that stuff when I was fifteen. Sometimes I'll see a movie poster for, you know, The Green Lantern, and think, if you'd have told me when I was thirteen that this would happen one day, I'd have just been stunned, so excited. Now I could not be less interested. So I don't think of it in those terms.

Somewhere in the back of my mind, I know that it's a label somebody else might put on [my book]. But I feel like The Death-Ray has a certain purity that's just divorced from all that.

TL: Do you think that the hardcover format changes people's perception of your work?

DC: Probably. I feel a lot more pressure doing something as a book. I used to use working in the comic format as kind of an excuse to not concern myself with how anybody would respond to it. I was like, "Oh, it's just a comic book. Just throw it away if you don't like it." But with a book, you have a certain responsibility to somebody whose paying twenty dollars, and it's gonna be a permanent item in their house. I feel like I need to fulfill the obligation of making it a worthwhile thing to sit on a coffee table somewhere.

TL: Do you think it draws a more "literary" association when it's a hardcover?

DC: That I don't know. I don't know how people respond to any of this stuff anymore, really. I don't know what anybody's points of reference are. All my books are sort of referring to old books I had when I was a kid. It's a like an old Golden book or a Tintin book that has this kind of, you know, presence.

TL: You've turned a few of your comics into screenplays: Ghost World, Art School Confidential. Are you working on a screenplay for The Death-Ray?

DC: I've witten sort of a movie version of it that I'm right now discussing with a director, but it's very different from the book—it's kind of an alternative version of it.

TL: Does the process of writing a screenplay change how you work?

DC: Yeah. I tend to almost work like a documentary filmmaker. Where the original object is kind of just source material, it's like I have found footage I can use in making a film. Then I try to turn it into something different, something that works as a film. It would be unbelievably dull to just recreate what I've already done on film. People probably would like to see that, but as the guy who's creating it, I have no interest in it. The movie would come out flat and dull. It's much more interesting for me to kind of take the elements of a story that I really like and recombine them in a new way.

TL: Does it ever change how you feel about a given work?

DC: Your opinion changes daily on all this stuff. There's never sort of a definitive conclusion that comes out of any of it, but you certainly examine it all from different angles.

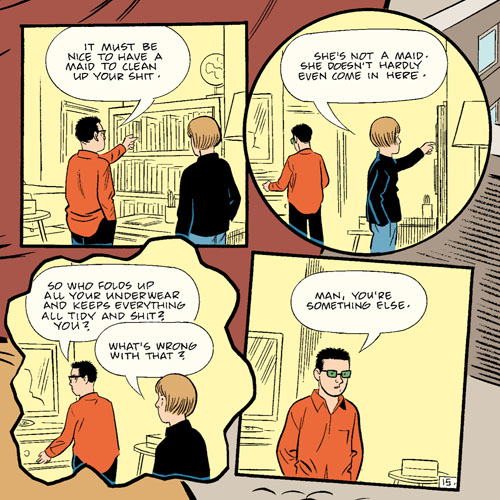

An excerpt from The Death-Ray.

TL: You've said in other interviews that you don't like the term "graphic novel." Why are you critical of it?

DC: I guess because I don't think its a good term. I think it's pretentious. I don't like the term "graphic." It has connotations, I think, that don't apply to what's being done. Most of the main graphic novels, like Maus and Fun Home and Persepolis, are not novels at all. They're non-fiction. [Graphic novel] is a term where somebody who actually cares about the English language will see what it applies to and think, "These people are stupid, using a really imprecise term."

But that being said, I've totally given up on giving a shit about it. I'm tired of talking about the term for this thing. People just sort of accept it now, and I'm just perfectly happy to use it. The other thing, too, is that for years I thought myself or one of my peers would come up with our own term that would actually be better, but nobody ever did. I'd be perfectly happy to just call them comics, but if people don't want to do that, then that's fine.

TL: It just kind of came to mean what you were doing, whether you liked it or not.

DC: It's one of those things like the Beatles, you know. "The Beatles" is the stupidest name ever for a rock band. Once every ten years I'll be lying in bed and think, "God, the Beatles—what a terrible name."

TL: I just got that joke for the first time a month ago.

DC: Yeah, exactly—because you grew up without it even being a thing. It existed. It's like a monument. I mean, "movies" is also a terrible name. Moving pictures! They're "movies!" But you know, we don't think about that, so I'm just gonna throw graphic novel into that category.

TL: As a sort of hokey term whose meaning doesn't really matter anymore?

DC: I've never seen any evidence of anybody else rolling their eyes at the term, so I guess it's just me.

TL: How did you shift from compilations and strips to long-form narratives?

DC: Even in the early Eightballs, I was doing long, continued stories. I was always interested in the long stories; all the short stuff was kind of just filler, in a sense. For most of my ideas, I'd love to have ideas that worked as a perfect little five-to-ten-page story—that's a great way to do comics. You can get almost anybody to read something that short. But I rarely have anything that doesn't take much more space than that.

TL: Is there an aspect of comic fandom that irritates you? You took digs at comics fans back in your earlier stuff.

DC: The last time I did one of those is fifteen, sixteen years ago. When I first started out in comics, the only way to sell these things, to get any audience at all, was to go to comic shows and stores or comic-book conventions. These [kinds of comics] were not in book stores.

I just found it this kind of queasy experience to be stuck in this world that really had no place for me. It wasn't that people who went to conventions liked comics; it's that they liked fantasy. They sort of thought that any kind of comics would be welcome at a convention, but you'd never have any people that were into our kind of stuff show up at those things, and it just got kind of deeply frustrating and alienating. I was doing this stuff that I thought was really interesting and should have had some kind of an audience, and it was frustrating that nobody was able to get into my work. I did those strips really out of frustration of being trapped in kind of a weird marketplace.

TL: Are you more satisifed with your readership now?

DC: I feel like now there's sort of a wide enough audience that I have my kind of readers, and they're sort of able to find out about stuff like my comics. They don't really have to have anything to do with the guys that read Game of Thrones, or whatever.

And you know, there's a way to sort of separate out the comics audiences—which is good. It used to be you'd tell somebody that you did comics, and you'd have to say, "Oh, you have to go to this dingy comic store across town and wade though action figures of guys with axes." And in the back there'd be a little box labelled "Adult," and you'd have to go through that on your hands and knees while sweaty comic-shop employees were looking at you. You weren't gonna tell your girlfriend's parents to go do that. But now I can just say, "Go to the book store," there'll probably be one in the humour section.

Daniel Clowes is touring with Guelph cartoonist Seth this fall. Their Montreal launch for The Death-Ray and The Greater Northern Brotherhood of Canadian Cartoonists, respectively, is at Ukrainian Federation (5213 Hutchison St.) on October 19 at 7 pm.

All images courtesy of Drawn & Quarterly.

Read a review of The Death-Ray in Issue 41 (Fall 2011).

Subscribe to Maisonneuve today.

Related on maisonneuve.org:

—The Comic Menace

—Generation Geek

—Interview with Michael Cho

Follow Maisonneuve on Twitter — Like Maisonneuve on Facebook