Anarchy in the QC

In the summer of 1977, one makeshift, beer-soaked venue brought punk rock to Montreal. Then the mafia showed up.

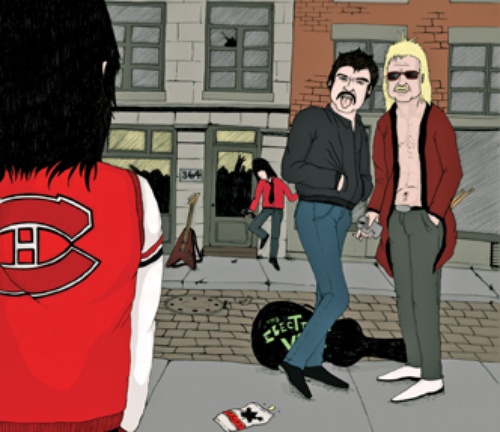

Illustration by Fred Casia.

Carlos Soria slinks down an Old Montreal street in a hockey jacket and blue jeans, broken streetlamps glowing overhead. It’s 1977, and Soria’s a burgeoning punk. He hasn’t found his tribe yet, or figured out the right clothes and chords, but he knows there must be something different in this town—something raging against the disco and hippie-hangover chansons that creep into every other part of Montreal. When Soria turns onto St. Paul Street, he sees a group of people standing in the middle of an otherwise empty road. They’re dressed like the English punks he’s seen in fear-mongering news reports about the Sex Pistols. This has to be the place.

From the street, the venue just looks like an empty storefront in a crumbling neighbourhood. Soria hears snickering about his jacket and jeans as he walks inside. Brushing aside a curtain made from what appears to be chicken feet, Soria moves into a space filled wall-to-wall with more punks than he has ever seen in one place—hundreds of them, all dressed like the small clique standing outside, but even snottier, louder, drunker.

On a makeshift stage at the back of the room, three men shout through a PA. The spoken-word Punketariat Poets, whom Soria learns are a staple of the scene here, scream and trade verses while dodging stubbies tossed by less literate audience members. The Poets finish with a shouted stanza about hand jobs. Then the Chromosomes, a local band more infamous for their drug consumption than their onstage talents, strap on guitars and tune up. They hurl an insult at the audience and do a quick count before launching into their first song: Led Zeppelin’s “Stairway to Heaven.”

Soria looks around, confused—what the fuck is going on? Why are they covering such a gaudy, mainstream song? But, almost immediately, the Chromosomes switch gears and slash into a driving track of their own that’s heavier and crazier than any English punk song Soria has ever heard. The audience launches gobs of spit at the band and empty bottles fill the air as front man Dave Rosenberg spews lyrical vitriol about Montreal, drugs and Batman. No one checks Soria’s ID as he grabs a beer from the bar and launches himself to the front of the crowd.

Robert Ditchburn didn’t have any real reason to rent the storefront at 364 St. Paul West. But for only $75 a month, he got two huge street-facing windows and a substantial loft space that stretched right to the back of the building. At the time, the Old Port was in decay, a collection of dusty bars and abandoned stores, and Montreal was in the throes of a strange cultural upheaval, stuck between growing American influence and swelling separatist ideology. Disco was the sound of the day, and the sovereignty movement was steadily growing more popular, reaching its apex with the provincial election of Réné Lévesque’s Parti Québécois at the end of 1976.

Early punk was built on an anti-establishment ethos and mistrust of authority, making it incompatible with nationalism—you can’t smash the state and create a new one at the same time. Quebec’s quest for sovereignty only encouraged those who sought a more radical alternative. Ditchburn himself was no anarchist; he was an apolitical McGill graduate who pretended to still be enrolled in order to rent equipment from the school’s audio-visual department. But in turbulent 1970s Montreal, it was easy to convince an eclectic collection of artists to help him populate and decorate the storefront. It opened the day after his deposit cleared. There was no paperwork, and there was no plan.

“We heard about it, but we had never been there,” says Tracy Howe, who worked in McGill’s AV department at the time. An early disciple of the new sounds emerging from London and New York, Howe and his co-worker, Scott Cameron, formed a fast friendship with Ditchburn, who borrowed equipment while they looked the other way. When Cameron and Howe finally formed a band, the Normals, they knew who to ask about a venue.

“There was no intention to put on punk shows,” says Ditchburn. “But before I knew it, we were putting on a show Friday night.” Until then, the space had been used primarily as an art gallery, hosting readings and parties for Ditchburn’s friends. True to form, the first punk night was a mess: bands sprung up out of nowhere for the chance to play at Montreal’s first proper venue for underground music. While some groups barely lasted through the evening, later pillars of the Montreal scene—the Normals and the Chromosomes—made their live debuts that night. (Now-legendary band the 222s would get their start at the space soon after.) Ditchburn filled a bathtub with ice and beer and sold it without a licence to the hundreds of thirsty revellers who filled 364. At the end of the night, someone got up to the microphone and said, “Come back. We’re playing next week.”

Ditchburn’s space wasn’t long for this world. Most estimate—their memories hazy from drink, their old show posters lost or crumbling in basements—that about four or five shows took place in the Old Montreal storefront that summer. But those few nights were defining moments: sweaty, cramped, raucous happenings that would never have been possible in a traditional venue or hotel bar. The space’s wide-open embrace of creative expression and multimedia approach left an indelible mark on those who attended. In a city that, today, boasts one of the most celebrated arts scenes in the world, being the first weirdos to plant their flag is a big deal.

But it wasn’t just outcast Ramones fans who heard about 364 St. Paul. One Monday afternoon, as Ditchburn was cleaning out beer bottles and dried vomit from the weekend’s performances, he looked out the windows and saw a limo pull up onto the sidewalk. Out stepped four men with necks like tree trunks. They walked into the store, looked around and waited. A last man, cutting an equally imposing figure, stepped out of the limo and entered.

“Montreal is its own old world,” Ditchburn says now. “Not as clean-cut as Toronto.” Even then, he understood that the mafia controlled most of the city’s nightlife, a shady aspect of Montreal culture that has never really gone away. He wasn’t sure how he got on the radar of the local famiglia, but as he stood in the centre of his space, he ran through the possibilities: maybe he had encroached on their territory; maybe he had been selling alcohol without their permission. Either way, they were probably going to kill him.

The last man spoke first. “I hear you’re running shows here,” he said. “So, this is a club?” Ditchburn tried to explain the nature of his storefront social experiment. The man offered to help manage the place. He said he could put a few plants up, even replace the bar, which was an old bowling-alley lane mounted on parking signs. He wasn’t angry, but he was insistent. The presence of a minor security detail made his point clear. Ditchburn asked for some time to consider the proposal, then did the only logical thing.

“I ran,” he says. “I didn’t want to be on the payroll when someone came around asking questions, or we suddenly weren’t making enough money.” Ditchburn closed the space down overnight. He never booked another show.

Just a few months after it appeared, 364 was gone. (The space now houses an upscale hair salon.) However, it wasn’t just the mob that had noticed the punk crowd’s endless appetite for booze; near-reputable local establishments like the Hotel Nelson were suddenly hosting punk nights, cramming as many skinny jeans and leather jackets as possible into their seedy bars, and reaping the benefits of customers who spat as much beer as they drank.

Montreal punk moved up and moved out. Bands learned how to actually play their instruments. Within a few years, a handful of groups entered the studio and made proper recordings. Punk was becoming a borderline respectable—or at least viable—style of music. The Chromosomes, the 222s and the Normals inspired a younger generation of Montreal bands to reject the velvet pants of their older siblings and strive for something louder, faster, more furious. Bands that took their cues from the first shows at 364 include the Electric Vomit, which featured future members of post-hardcore stalwarts the American Devices, and Carlos Soria’s band the Nils, a crucial early influence on nineties grunge. The eighties saw punk shift into upscale bars and discotheques. But in Montreal, its heart remained somewhere behind the bowling-alley bar of 364 St. Paul.

Originally published in September 2011. See the rest of Issue 41 (Fall 2011).

Subscribe to Maisonneuve today.

Related on maisonneuve.org:

—Take the Skinheads Bowling

—Buffy and Sheena are Punk Rockers

—Alex Chilton (1950-2010)