Unleashed

Two years ago, an Ontario man was killed by a Siberian tiger—one he kept in his own yard. Nobody knows how many other deadly pets might be prowling Canada’s suburbs.

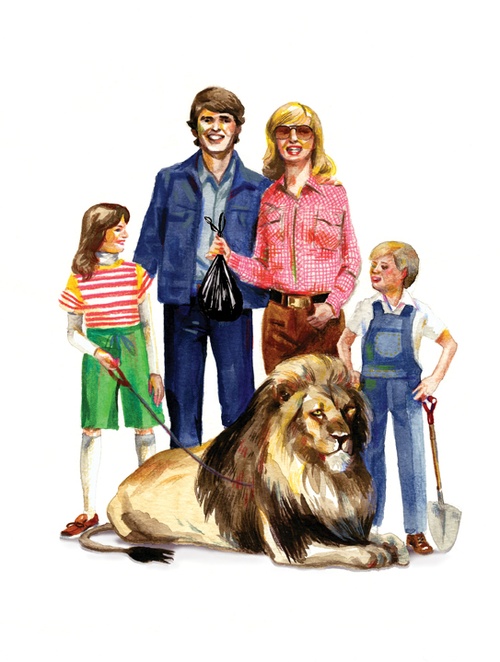

Illustration by Team Macho.

"Do I hear eight-thousand-eight-thousand-eight-thousand? Do I hear nine-thousand-nine-thousand-nine-thousand?” The auctioneer’s tenor echoed through the huge, cold room, the smell of feces and grease thick in the air. A gasp rippled through the two-hundred-strong crowd as we saw what stood in the ring: two Grant’s zebras, hostile and nervous.

I drew back slowly from the green steel bars, the only things separating me from the prancing animals. I was not used to seeing zebras, native only to Africa, two metres in front of me. Although they resemble horses, zebras are surprisingly vicious when kept in captivity, making them nearly impossible to tame. But now the MC rubbed the male’s side, showing the audience how “domestic” the pair was. The crowd emitted the requisite aw.

Some attendees looked on, thrilled. Others made sure their children were seated firmly on the ground, far from the bars. It was hard to tell who was buying and who was just curious, who was an activist or a journalist. I was at an animal auction, one of two held by Tiger Paw Exotics each year, and the crowd was a curious mix of trucker hats, NASCAR jackets, mullets, bleach-blonde hair, knitting needles and quilts. Most attendees were tough-looking farmers. There was also a grey-haired man in a clean black suit, accompanied by his trim wife and young son—possibly the owners of the silver BMW parked outside. Black-clad Mennonite families lined the top benches at the back of the room. They were presumably here to buy sheep or goats, not zebras or exotic birds or golden Mongolian horses, which looked like Shetland ponies but stomped their hooves aggressively. Serious buyers flicked their auction cards, which had numbers drawn on in magic marker. The auctioneer and MC watched for the lightning-quick flashes of upheld pink.

These so-called Odd and Unusual Sales have run for the past ten years at the Ontario Livestock Exchange in St. Jacobs. (Tiger Paw also runs a petting zoo in Arthur, Ontario, sells animals to private collectors and provides creatures for film and TV productions.) There are few such events in Canada, making the Odd and Unusual Sale a significant draw for exotic pet owners and breeders across the country. At this particular auction, master of ceremonies and Tiger Paw owner Tim Height stood in the ring, microphone to his lips, wearing a cowboy hat and zipped-up black nylon jacket with his company’s logo embroidered on the back. Most people in the room seemed to know him personally. As the animals came up for auction, Height entered the livestock pen, showing off the wares and supplementing the auctioneer’s yelp with details about the animals. All were being sold on consignment for other people.

The auction began with llamas, alpacas and donkeys. After selling off the horses, Height set up a projector to promote a selection of the coveted exotics using blurry shots from a video and a PowerPoint presentation; some of the exotic pets—lemurs, cavies, cervals—were being kept just outside St. Jacobs’ municipal boundary, due to a fuss the locals kicked up that year. “If you drive ten minutes down that road, we’ll meet you and conduct the exchange there,” he assured the crowd. Until this year, all the animals had been present for inspection. (The county has since decided to ban the auctions entirely.)

Height—who declined to be interviewed for this article—bought the zebras himself, the male for $5,000 and the female for $6,000. Likely to breed them, commented the rotund man in the red baseball cap sitting beside me. The man and his wife, both in their mid-forties, kept llamas and snakes at their London, Ontario home, and they had been coming to Height’s auctions twice a year, every year. “We started with horses,” he said. “We’ve been coming to these auctions for ten years. A few years in, we saw a llama and decided we could do it. So, we bought one.” He refused to give me his name. “Are you an activist? What group are you from?” he asked, not quite believing me when I told him I was a journalist. The serious buyers at the auction were quiet, focused, suspicious; I was asked three more times which animal-rights group I represented.

Following the zebras and other exotics were the sheep and goats. Finally, Height hit the miscellaneous section, the auction’s grand finale. This felt more like a rummage sale—bring on the peacocks, rodents and snakes. There was even a box of porcelain turtle figurines, which sold for $1 apiece. Height shouted out sale confirmations in rapid succession as his assistants hauled out a seemingly endless stream of small animals—some in wooden crates, others in plastic tubs with hole-punched lids—and sold them off.

In the last few minutes, out came the sugar gliders, flying squirrel–like animals native to Australia. Height admitted that they were among the animals “we’re not supposed to have. Shhh.” He grinned. Pens and containers packed with animals now filled the auction ring. A cage holding a scraggly-looking peacock crashed to the floor. No one said a word. Two assistants quickly carried the dazed bird away, its plumage crushed beneath the metal mesh.

People adopt pets for a variety of reasons. Some simply love animals; for others, pets are a social lubricant, an easy way to meet new people. Perhaps above all, bonding with animals is a way to combat feelings of loneliness and depression. “Pets can clearly provide the emotional attachment bond important in promoting a sense of security and well-being,” wrote the authors of a 2003 article in Professional Psychology. Companion animals “can provide a sense of ‘nonjudgmental’ social support.”

Undomesticated exotics are hardly typical companion animals, but try telling that to their owners. Although plenty of research has been conducted about the care and treatment of exotic pets, virtually no work has been done on the psychology of exotic-pet ownership. What would drive someone to buy a zebra? Why would someone keep a crocodile in the bathtub, or a cougar in the basement? Different owners offer different motivations: a lifelong affinity for animals; a childhood of horseback riding; an awe-inspiring experience at a game farm in Africa. But none of these responses truly explain why a person would take on the considerable risk of owning a large, potentially deadly animal.

Owners insist that their passion—which has cost some of them homes, families and careers—is for their animals. But those who work with (or against) exotic-pet owners agree that there is one fundamental impetus, something evident in every owner, whether the prized possession is a tiger, python or monkey: ego. What owners all seem to share is a yearning for the emotional high that comes from possessing a wild animal—from controlling a part of nature that was once untamed.

Owning exotic pets can be undeniably dangerous. In 2010, an Ontario man was mauled to death by his pet tiger—the same animal that had attacked a ten-year-old boy several years before. Five years ago, a woman near 100 Mile House, British Columbia, was killed by her fiancé’s Siberian tiger. In New York last year, a black mamba bit and killed its owner, who also kept over seventy-five other snakes, most of which were poisonous. This risk doesn’t affect owners alone: neighbours are endangered when the animals escape, and emergency workers face the threat of entering a home inhabited by an unregistered pet. Also at stake is the well-being of the animals themselves, cared for by collectors who are often untrained and unchecked. That’s particularly true of Ontario, the only Canadian province that doesn’t require licensing to keep dangerous exotic pets. There, you could live next to one of the most vicious predators on Earth and not even know it.

I met Tony Porter at the Tiger Paw auction. He’s a tall man with a paunch, a long white beard and a mustache that curls up at the ends. He walks with a cane and wears a gold belt buckle. Porter is a reindeer breeder who works part-time doing maintenance on rifles for the Canadian Forces’ cadet programs. His other part-time job is dressing up as Santa Claus.

Porter remembers horseback riding with his father as a child, heart thumping in his chest, taken by his steed’s majesty and presence. He remembers the first horse he ever bought. And he remembers the day his eldest daughter, Katherine, came home with a three-day-old lion cub.

“I said, ‘Absolutely no lions in my house,’” he recalls. But Katherine, an animal educator for schools in southern Ontario, wanted to keep it, and, Porter reasoned, it was only six months old. He figured that T.J. the cub was young enough to be trained. They had the space and the resources. He was excited by the challenge; imagine if he could tame a lion. “If you asked me if I would do it again, I would,” Porter says. “But I don’t think everyone should. I don’t think it should be a regular thing. It was always going to be just until it was six months old.”

Before long, T.J. was sleeping between Porter and his wife in their bed. Porter won’t say where T.J. came from, but once the six months were up, the animal was placed at an Ontario zoo, where he still gets regular visits from the Porters. In addition to breeding reindeer at his farm in Shelburne, Ontario, about an hour and a half outside of Toronto, Porter keeps two exotic birds, three lemurs and two coatimundis (raccoon-like animals native to South America). Jackie, Porter’s six-year-old pet kangaroo, rides shotgun in his car.

Although Porter doesn’t have formal animal-care training, he says any owner can become knowledgeable fairly quickly, thanks to the internet. Indeed, the web has changed the rules of the industry, both by offering massive amounts of information and facilitating trades that were once much more logistically complex. At a March 2010 meeting of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species, an international regulatory body for animal trading, the 175-nation panel concluded that the internet poses a major threat to endangered species because it fuels the worldwide exotic-pet trade. According to a 2008 survey conducted by the non-profit International Fund for Animal Welfare, within just one six-week period, $3.8 million US worth of exotic pets and animal products were advertised on online classifieds, auction sites and chat rooms. The sale of everything from parrots to polar bear skins—more than seven thousand different species were available—primarily occurred in the United States, but also in Europe, China, Russia and Australia.

But Porter insists one positive consequence of the boom is that most buyers now want consistent regulation. As it becomes easier to acquire animals, he says, serious owners want to ensure standards of care are enforced. In Canada, however, exotic-pet ownership is governed by a mess of conflicting provincial and municipal regulations; some provinces and cities ban specific species outright, while others offer only lax rules or vaguely worded guidelines. Porter is spearheading an initiative called Animal Enthusiasts Ontario, which will lobby the provincial government for better, more consistent standards. His concern, he says, is for the animals—but he also wants to make sure the province can’t seize his pets. That kind of disruption could be threatening and disturbing for the animals, Porter argues. He makes no mention of how it would hurt him.

When we speak on the phone three weeks later, Porter tells me his wife left him the day he came home from the Tiger Paw auction. He won’t say why, or whether his animals played a role. Did she share his passion for them? “I thought so,” he says. “I don’t want to talk about this anymore.” She didn’t take the kangaroo.

Rob Laidlaw began collecting reptiles when he was thirteen. It started innocently enough, with the small North American corn snake he kept in his bedroom. His collection grew to include more snakes, then lizards, then tropical fish—until, one day, the then-fifteen year old simply stopped. “If I like these animals,” he thought, “I shouldn’t be keeping them like this.” Laidlaw is now a biologist, Canada’s pre-eminent animal-rights activist and the executive director of Zoocheck, a charity that focuses on the well-being of animals in captivity. He subscribes to the ego theory of exotic-pet ownership. “A lot of people increase their self-worth because they surround themselves with animals and gain attention from other people,” he says. “You can be any Joe, but you walk down the street with a tiger on a leash, and you’re going to get attention.”

Of course, you can’t own a tiger just anywhere. Most provinces and territories require licences to keep exotic animals, reserving the right to enact bans when deemed necessary; the government of Prince Edward Island, for example, has successfully barred people from bringing pets like alligators to the island. In British Columbia, thanks to a 2009 law, 1,300 species are banned or require a permit, including giraffes, rhinoceroses, long-tailed macaques and furry-eared dwarf lemurs.

Then there’s Ontario. “It’s no secret Ontario is the Wild West for the exotic-animal trade in Canada,” Laidlaw says. Owners have abandoned live crocodiles at the Toronto waterfront. Pythons have gone rogue, escaping through the walls of condo buildings. Ontario does not have province-wide regulations; instead, a confusing patchwork of municipal rules allows lions in some jurisdictions and forbids jaguars in others. In some provinces, government agencies can track, inspect and seize animals if they so choose. But in Ontario, under legislation passed in 2009, the only province-wide standardized rule specific to exotic wildlife is the Ontario Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals’ power to inspect roadside zoos if there is cause for concern. Neither the OSPCA nor the province has authority over private collectors.

Ontario government officials say they are reviewing existing policies and looking into the Provincial Animal Welfare Act. Laidlaw, however, argues that the government has been saying this for twenty-five years. “They don’t want to touch this,” he says. “They have a public line that says they’re concerned; they recognize it’s a problem that needs to be dealt with. When it comes down to brass tacks, they never do anything about it.” Last November, Liberal MPP David Levac brought forward a private member’s bill that would see exotic animals regulated by the province’s Ministry of Natural Resources. Activists say it’s a step, but the success rate of private member’s bills is low, and no second reading has yet been scheduled. One of the few things on which exotic-pet owners, activists and experts agree is that regulations are necessary to penalize irresponsible owners and monitor how many exotic pets reside in the province. But that consensus falls apart when it comes to deciding which level of government should be responsible for regulation, and how far the government should go—whether it should employ a permit system, an outright ban or something in between.

Laidlaw estimates that there are five hundred to two thousand large exotic cats kept as pets in Ontario. But he admits he’s shooting in the dark. “All you have are educated guesstimates,” he says of his tally. “It’s anything from ocelots”—small leopard-like cats—“to tigers.” I notice he seldom mentions cooperating with the owners themselves. When I ask why, Laidlaw sighs. “For the first ten or fifteen years, we did try to collaborate more with people and work on reform measures to the system,” he says. “What we found was, when it comes down to it, they don’t want to do anything.”

Ontario’s non-accredited roadside zoos are part of the problem. Because of lax regulations, anyone can throw a few coatimundis in a cage, put up a sign and call the operation a zoo. Many roadside zoos in Ontario offer educational programs to visitors, and some have partnerships with schools. The problems start, experts say, when the zoos turn around and sell exotic animals to interested buyers, encouraging irresponsible pet ownership. Some private zoos survive by charging admission, just like publicly funded zoos—but according to exotic-pet owners I spoke with, they also breed animals as large as tigers and sell them to visitors who ask the right questions.

Roadside zoos and animal sanctuaries have also faced criticism about poor treatment of their creatures. In 2005, the World Society for the Protection of Animals published a scathing report on the conditions in Ontario’s roadside zoos. The audit, conducted by Dr. Ken Gold, a twenty-five-year veteran of some of the world’s preeminent zoos, concluded that few roadside zoos treated their animals with standard-quality care. “Many non-accredited zoos appear to be breeding their animals with no plan for the future of the young, or perhaps to supply other roadside zoos with baby animals,” Gold wrote in the report. “These roadside zoos can only hold so many lions, tigers and other big cats, yet places like Northwood Buffalo and Exotic Animal Ranch [in Seagrave, Ontario] seem to be breeding big cats like rabbits. Without proper facilities or a coordinated breeding program, these zoos are a powderkeg waiting to explode.”

Although a WSPA poll conducted in Ontario last year found that 79 percent of respondents would support an outright exotic-animal ban, the provincial government hasn’t budged. It leaves those rules to its municipalities. In Toronto, a bylaw lists animals forbidden within city limits, including elephants, bears, non-human primates (chimpanzees, gorillas, monkeys or lemurs) and Crocodylia (alligators, crocodiles or gavials). The bylaw also says you can’t keep any venomous or poisonous animals, snakes longer than three metres or lizards longer than two metres. But in Southwold Township, near London—where longtime big-cat owner Norman Buwalda was killed in January 2010 by his pet tiger—you don’t even need a permit to keep a big cat in your backyard.

Two stone lions mark the gateway to Buwalda’s former estate. A painting of a tiger adorns the nearby mailbox, and, until recently, passersby could catch a glimpse of the real thing: a 650-pound Siberian tiger kept in a large, meticulously designed building with double-door security. Then, in 2010, that same tiger mauled and killed its sixty-six-year-old owner.

Buwalda had been a tireless proponent of exotic-animal ownership rights in Ontario. But after his death, he became the poster child for both sides of the debate. Fellow exotic-cat keepers respected his fight to hold on to his animals, and they see his fate as a tragic accident. More frequently, though, he’s cited as an example of why Ontario needs stronger laws to protect public safety. Following the attack, Premier Dalton McGuinty offered his condolences to Buwalda’s family, and promised to revisit the province’s exotic-animal policies—but he also reiterated that ownership regulations should be a municipal responsibility.

Buwalda, a wealthy, eccentric businessman who owned a metal-fabrication company in nearby Strathroy, had kept as many as three exotic cats on his property at a time for as long as his neighbours can remember. He wasn’t beloved in the community. He first came to the media’s attention in June 2004, when the tiger who would eventually kill him also mauled a ten-year-old boy. The cat had been taken from its cage in Buwalda’s yard to pose for photographs, and the incident led angry neighbours to demand a township bylaw banning anyone in the municipality from owning exotic pets. It passed at council, but Buwalda didn’t give up. He challenged the bylaw, and the case went to the Ontario Superior Court in October 2005. Buwalda’s lawyer, Alan Patton, argued that the bylaw infringed upon his client’s right to decide how to use his private property. The township’s lawyer countered that the bylaw was needed for public safety. Three months later, Justice John Kennedy decided in favour of Buwalda and nixed the bylaw, ruling the municipality’s process “flawed” and saying it demonstrated “bad faith.”

Neighbour David Rawson, one of Buwalda’s fiercest critics, says he never worried about safety when the animals were kept in their enclosures. But it enraged the community when the cats were let out to roam around Buwalda’s estate, or to pose for photos with visitors. “Should that tiger have gotten away after he mauled the boy, what would have stopped him from galloping into the woods?” he says, adding that Buwalda’s property wasn’t fenced in. “We’ve had family not want to sleep in the tent in the summertime outside. If you were around, you could often hear the growl of the animals.”

Rawson, who lived near Buwalda for more than ten years, says his neighbour was a private man, who lived alone on his sprawling estate with his big cats. “I think he would say that his friends were animals,” he says. “I don’t think he felt like he had a bond with humanity.” Strathroy-Caradoc mayor Mel Veale, who was Buwalda’s next-door neighbour for years, told the London Free Press that Buwalda was a risk-taker. He once introduced Veale to his big cats, and she noticed that he “had that way about him that he commanded an animal’s attention. He had absolutely no fear of them, no question.”

The Ontario Provincial Police won’t reveal what happened to Buwalda’s animals, saying only that it removed a tiger and two lions from the property after the man’s death and placed them in an undisclosed location. “As far as what’s being done with the animal, at this point it’s up to the family,” says OPP officer Troy Carlson. “What would you do with the animal if somebody went into a cage at the zoo and got mauled? Would you put the tiger down? No.”

In 2009, British Columbia’s Minister of Environment, Barry Penner, held a press conference to announce a long list of animals now banned from the province. The ban—motivated by a 2007 incident in the community of 100 Mile House, when a pet tiger killed a woman—would cover 1,300 species not native to BC. Owners whose animals arrived in BC before March 16, 2009, might be able to keep them, he said, if they applied for and were granted a permit. If they want to go a step further and transport or display the animals, owners must now be accredited by the Canadian Association of Zoos and Aquariums. The new rules also carry stricter penalties: offenders can land fines of up to $100,000, or spend a year in jail.

While blanket bans like this make it harder to acquire animals, Bry Loyst, the curator of the Indian River Reptile Zoo near Peterborough, Ontario, says they don’t ensure that existing collections will be well-documented or tracked. “Why not move to Ontario where you can have your pet rattlesnakes,” he says, “instead of Quebec where you can’t?”

According to the World Wildlife Fund, there are more privately owned tigers in the United States than there are in the wild around the world. Advocacy organizations estimate the exotic-pet trade in the US to be worth $15 billion us. Washington regulates the import and export of exotic pets through the Department of Agriculture, and in nine states, pets considered exotic or dangerous are banned altogether. But, as in BC, bans don’t necessarily work. Exotic-pet auctions are larger and more frequent in the US, says Rob Laidlaw, and its pet trade is far more active than Canada’s, bans or no bans. The global community does make some effort to regulate the worldwide exotics trade through the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species. But participation in CITES is voluntary, and it doesn’t supersede national laws. Bans are costly to enforce and aren’t often among politicians’ top priorities—until a death or injury makes the news.

Paul Malagerio gets up early in the wintertime. Sometimes it’s 4 am, sometimes 5. If he has a girlfriend staying over, he leaves her sleeping, climbs out of bed and puts on his snowsuit. He trundles out into the backyard of his Madoc, Ontario home, unlocks a door and walks through a fenced-in area. He enters an enclosure made of solid wood with steel beams, which looks like a shanty house, front yard and all. Inside, he lies down on the frozen mud and curls up beside Nicky. “To my last girlfriend, I used to say, ‘Sorry, but this is where I want to be in the mornings,’ you know?” Malagerio says.

Nicky is a four-year-old cougar. Malagerio bought him for $1,000 from a roadside zoo in Bracebridge, Ontario. Cougars—also known as mountain lions or pumas—are found throughout the Americas; in North America, they’re native to the continent’s west, from northern British Columbia through Texas and Mexico. Malagerio fell in love with big cats when he worked on a game farm in Africa fifteen years ago. “I knew I had to own one,” he says of the lions he saw there. When he returned to Ontario, he began to work at roadside zoos, until he eventually decided it was time to commit. Nicky weighed fifteen pounds and was five weeks old when he came home with Malagerio. “I let him out of the car, and turned around and walked away,” he says. “I felt something furry around my ankles and I looked down and there he was. And he’s never left my side since.” Nicky now weighs approximately 190 pounds.

Malagerio argues that Nicky is not an exotic pet because cougars are native to Canada. (There are even occasional mountain-lion sightings in Ontario forests.) But his neighbours may not feel the same way. “I’ve been shot at,” he says. “I don’t know by who.” Malagerio doesn’t work; he had a heart attack last year, which he attributes to the stress of fighting for Nicky. After arguing against a new ban on exotic pets in Prince Edward County, where he used to live, he moved north to Madoc and, he says, gradually won over most of his neighbours. (Convincing the home insurance company to take him on was another story.)

Neighbours and roadside-zoo owners have told Malagerio that mountain lions don’t like to be touched, but he says that’s not true. “If I’m not touching my cat, he’s touching me,” he says. “We sleep together. I make motorboat sounds in his belly and he’s never bit. He goes, ‘Oh, Dad, you’re silly.’” Malagerio throws Nicky a birthday party each year; he invites his friends, serves birthday cake and gives the cougar presents. He doesn’t blame Nicky for forcing him to move, or for alienating his neighbours. “I have a responsibility,” Malagerio says. “And at the end of the day, I just want to be with my son.”

The print version of this article referred inaccurately to the states in which Tony Porter rode horses as a child, the source of his passion for animals and T.J. the lion cub's age. Maisonneuve sincerely regrets the errors.

Originally published in September 2011. See the rest of Issue 41 (Fall 2011).

Subscribe to Maisonneuve today.

Related on maisonneuve.org:

—A Zoo Story

—Could Ohio's Zoo Escape Happen in Canada?

—This Little Piggy Went to Market