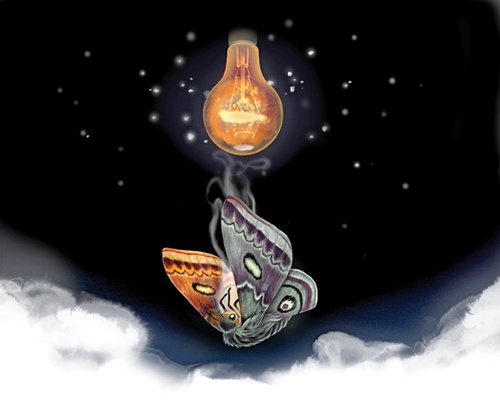

The Moths of Burning Man

At Nevada’s most famous festival, Chris Urquhart flies too close to the flame.

Illustration by Byron Eggenschwiler.

Iris stands naked, save for a beige thong. She’s shameless and unafraid, arms spread and slathered in gold glitter and Vaseline. Atop her head sits an oversized hamburger hat—puffed yellow buns, brown patty, a plush pickle like an outstretched tongue. She grins maniacally.

We’re at Burning Man, the sprawling festival that, every summer, attracts yuppies, hippies, druggies and queers to northwestern Nevada. The one time of year when over fifty thousand North American freaks swarm the desert. At Black Rock City, the horde builds infrastructure and installations, huffs inhalants, dances hedonistically, tries to hear God. In the end, the iconic wooden Man is burned back down to the ground, and the impermanent settlement disappears.

I drove to the Burn with Iris, whom I haven’t seen since university. After graduating, Iris came out, moved to Brooklyn and found work taking her clothes off in strip joints. “I cater to a niche market at the club ’cause I don’t spray tan,” she tells me, still wearing the hamburger hat. She picks sparkles from her manicured nails and flicks them away. She’s Jim Carrey meets Carmen Electra; a glass of white wine mixed with powdered ketamine. Her body glitters in the Nevada moonlight.

“Let us begin by calling in the chakras,” the pseudo-guru in the white dashiki robe says. “Lam, Vam, Ram, Yam, Ham, Om.” He is leading a free seminar that promises to teach his students to overcome anxiety through breathing exercises. It’s held in a white yurt near my campsite. I’m wilted, exhausted from the previous night. I’d spent hours dancing atop cars with Iris, thrusting our bodies against the desert night; high, high, high. I’m attending the workshop to calm myself down, to start following the tips that mental-health professionals and professionally healthy folks have bestowed upon me. Back at camp, Iris cooks hot dogs.

Mist sprays from the top of the yurt. We sit in a circle: stoned hippie couples, elderly nudists, a middle-aged woman wearing an afghan, a teenage goth girl with eyes painted on her breasts. “Lam, Vam, Ram, Yam, Ham, Om,” I chant along. Having lived for two years among crystal wizards in Vancouver, I’m not put off by the chanting. It’s soothing. I am secretly hoping, however, that we might kick things up a notch. Dashiki pulls out a small tube.

“Inside this vial is a mixture of moonflower, herbs and pure grain alcohol,” he tells us, perched in the centre of our circle. “It will help clear your nasal passageways.” I try to look past his LA-wanker aura and squirt the tasteless liquid on my tongue.

Dashiki gives us a new phrase to chant in unison: “I am happiness. I am full acceptance. I am equanimity.” I repeat it. I can feel my fingers tingling and suspect I must be doing something right. I start chanting a little too enthusiastically. “I am happiness. I am full acceptance. I am equanimity.” The tingling spreads up into my wrists. “Happiness, full acceptance, equanimity.” I realize I’ve forgotten the meaning of the word “equanimity.” I scan my mental dictionary. My mind has gone blank. “Equanimity, equanimity, equanimity.”

“Look in the eyes of those around you,” Dashiki instructs us. “You are literally looking at everyone who has ever existed.” All I see are the eyes of others: tearing, winking, watching. Eyes on limbs, foreheads, breasts. Eyelashes fluttering. Dashiki mentions something about the Pleiades star cluster, sacred languages, other things that don’t make sense. My blurry mind, suddenly frantic, starts to spiral. Within seconds no sound sounds like language.

Moths are lunar beings: they follow the light of the moon. For the last hundred years, though, moths have been dying in enormous numbers. Electricity has perverted their flight paths. Some scholars believe that, instead of following the moon as their horizon point—as moths had done for millennia—they now fly to any light source available. One by one, junkies of luminance cut loose from the pack and nose-dive into traffic lights and neon signs. Everyone has seen moths at night, smashing their fragile frames against bright, hot bulbs. Committing certain suicide.

The tingling in my limbs has turned to cramping. My arms and legs snap into my body like a crab retracting its claws. I fall on my back, gaze stuck upward, eyes open. My forearms and legs jerk and flap up and down, a broken moth trying to take flight. I can hear a woman screaming, though I can’t turn my head to see her. I hear the gasps of exasperated hippies.

Through a hole cut at the top of the yurt I see the Nevada sun. The sky looks serene: blue, clean, even. No clouds. Someone asks me to release. A moment of calm comes over me; my limbs stop shaking. Then—drugged or not, terrified or not, alive or insane—I’m nothing but calm, nothing but release, nothing but “yes” and “sure” and “okay.” I’m yes even to Dashiki, who sits beside me like a weary, robed vulture.

“You really let go of a lot there, sister,” he says. A small water pipe breaks at the top of the yurt, and a stream begins to drip directly onto my face. It hits my forehead, my cheek, my tongue.

“Did everyone see that?” Dashiki whispers dramatically. “The fairies are helping her through this tough release.” Hippies gasp. I laugh at the lunacy of his statement, at our bizarre shared predicament, but nobody notices my response. They’re too busy focusing on their own fairies.

Moonflower (datura stramonium) is not, in fact, a decongestant, as Dashiki introduced it to me. It is actually a profoundly dangerous and mind-altering entheogen that has been used for centuries by shamans and mystics. It is a nocturnal species. Night-blooming petals splay open in the moonlight, waiting to be pollinated by lunar moths.

Moonflower has been nicknamed “the suicide plant” for its tendency to drive those who consume it to madness and self-harm; it causes amnesia, so those who ingest it often forget that they’ve done so. It is also called “Jamestown weed,” named after Jamestown, Virginia, where, during Bacon’s Rebellion in 1676, some British soldiers accidentally ate the plant. According the historian Robert Beverley Jr.’s 1705 book The History and Present State of Virginia, the soldiers went insane for the next eleven days. “In this frantick Condition they were confined,” he wrote, “lest they should in their Folly destroy themselves; though it was observed, that all their Actions were full of Innocence and good Nature.”

During my first visit to the Burning Man urgent-care clinic, I’m treated by a woman in a naughty-nurse outfit who gives me two cups of Gatorade and tells me to chug. On my second visit, several hours later, I’m hooked up to a freezing IV bag, laid back on a stained lawn chair and told to “chill out.” After a few hours, they release me back into the desert.

As the day melts on, I’m gripped by an angry, alien sense of doom. This is not normal, the thoughts say. Something went too far. Then, the most dangerous one: This is all in your mind. You are finally going crazy. By this time my memory of ingesting the moonflower is all but gone, and I decide, since the medical facilities aren’t helping and there are no buses leaving the festival, to barricade myself in my tent and try to relax.

“Lam, Vam, Ram, Yam, Ham, Om,” I say. “Ram, Bam, Ham, Spam.” But it doesn’t work. It only elevates the anxiety, reminds me of the seizures, the pain, the fall. Inside my tiny plastic tent in the middle of the desert, I’m gripped by a type of panic I have never experienced before. I’m burning up. And the thoughts, the thoughts, the thoughts. I hit my head with closed fists—the only way I can think to stop the looping, bug-eyed thoughts. I hit and hit but they don’t stop, and neither does the incessant hum outside my tent. The hive, the bass, the brass, the swaying vulgarity of men and women dressed in faux-fur short shorts. I can feel the Gatorade and IV saline bulging in my bladder. You are going crazy. And now you are going to piss your pants. Too terrified to leave the safety of my tent, I empty a two-pound jar of cashews and almonds onto the floor, pull down my pants and piss convulsively. Small husks and shells float, suspended in the hot yellow liquid, tiny planets in an ether of urine. Perched above the jar, weeping, I realize I am officially losing it. I unzip my tent. “I’m scared I’m going to hurt myself,” I tell a friend sitting outside. “And I don’t know why.”

The third time I receive medical treatment, I arrive at the clinic in an ambulance. Inside the screaming vehicle, a paramedic asks me soft questions. “Do you have a history of anxiety? Mental illness? Allergies? What’s your mother’s first name? Is this your first time in Nevada?” The paramedic attaches a blood-pressure gauge to my shaking arm and pumps. “Have you always had high blood pressure?” I have not.

Later, someone walks me to the Sanctuary—Burning Man’s makeshift mental-health ward. The Sanctuary is where the most creepy, frothing freaks end up, where Black Rock Rangers named Elmo feed you shrimp cup-o-soups and bathe you in psychobabble. No amount of Gatorade in the world can save you here. I’m tucked into a camping cot and covered in a rainbow blanket. Sick people are scattered across the room—stoners, burnouts, burnt bodies with white bandages. For the next twelve hours, I dip in and out of consciousness.

In her essay “Death of a Moth,” the author Annie Dillard describes watching moths dip into flames, self-annihilating in their attraction to light. She explains how one particular moth flew face-first into a candle, then acted as a wick, burning on:

She burned for two hours without changing, without swaying or kneeling—only glowing within, like a boiling fire glimpsed through silhouetted walls, like a hollow saint, like a flame-faced virgin gone to God, while I read by her light, kindled while Rimbaud in Paris burnt out his brain in a thousand poems, while night pooled wetly at my feet.

It is a natural instinct to fly into the light, even though the process is profoundly painful. It is the fear of burning that hurts, not the flame itself.

I’m awoken in the middle of the night by firecrackers. In the Sanctuary I can hear them but not see them. I imagine tiny bursts of electricity in a black sky. In my mind they’re shimmering purple insects, shot willy-nilly. Am I lost? Have we gone too far? Comfort comes as the fireworks blast on. The pangs of anxiety subside, and I feel, for the only time in my life, like I have reached some sort of destination. Cocooned in a tacky rainbow comforter, surrounded by sleeping visionaries and vicious seers, I realize I’m still alive. I have made it through.

There is a picture of Iris from the Burn, taken the night before my first hospital visit. She is standing on the desert floor, dressed in a fuzzy camouflage one-piece bodysuit. She looks unhinged but completely self-possessed. Impenetrable. The entire photograph frame is filled with white, iridescent orbs—perhaps stray sand particles that got stuck on the camera lens—but in the photo they look like tiny moths, circling through the desert night. Iris stands in the centre of the frame, staring, mischievous, higher than I have ever been and totally unfazed by the hundreds of other universes at her fingertips.

“Take me back to Reno,” I tell Iris in the morning, when I am strong enough to walk, and then I fly home. se.