John Cage's Canada

The twentieth century’s most important avant-garde composer may have been American, but he found his greatest inspiration north of the border.

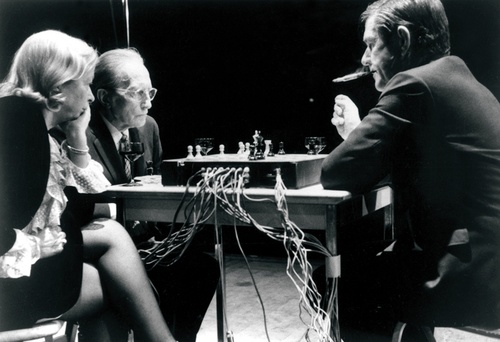

Marcel and Alexina “Teeny” Duchamp join Cage for a performance of Reunion in Toronto in 1968. Photograph by Shigeko Kubota. Courtesy of the John Cage Trust.

John Cage was lost in the woods. It was the evening of August 23, 1965, and the American composer was in Emma Lake, Saskatchewan, to give a lecture at an artists’ workshop. Although he’d briefly strayed off course on a mushroom-hunting expedition a week earlier, he hadn’t learned his lesson. “Found a large stand of Hydnum repandum. When others left for a nearby lake, refused to leave,” he wrote in his journal that night. “Arranged to meet on road at 4:00. 3:30 started back. 4:00 hurried. 6:30 lost. Yelling, startled moose. 8:00 darkness, soaked sneakers; settled for the night on squirrel’s midden. (Family of birds; wind in the trees, tree against tree; woodpecker.)” Alone in the muskeg, Cage noticed every movement, every sound.

The next day, after a dramatic rescue (even the RCMP got involved), Cage listened to a piece by a student at the workshop and had an epiphany. “Hearing several recordings of his music, was struck by difference between sections, no transitions,” Cage’s journal reads. “Suggested carrying this to extreme (Satie, McLuhan, newspaper): not bothering with cadences.” In music, cadences are resolutions of harmony that serve as signposts. Doing away with them, as Cage wanted, is much like doing away with punctuation in writing. It means that listeners are likely to feel disoriented.

Audiences still struggle with Cage’s music for exactly this reason. After returning from Emma Lake, he wrote Variations VI, a work that exemplifies the difficult experience of listening to Cage. Variations VI, which premiered at what is now the Art Gallery of Ontario in 1966, is a hodgepodge of electronic circuitry, microphones, radio, tape and TV. It is maddeningly noisy and hard to navigate. But that may have been Cage’s intention. He hoped that his music would encourage people to live and think freely by paying attention to chaos. Cage understood that liberty can feel, at first, like getting lost.

From the sixties through the eighties, Cage traveled to Canada frequently. As David Rosenboom, who often played Cage’s music north of the border, says, “He loved the landscape because it was vast and flat, like looking on a white canvas—this very open plain on which you could imagine things.” Or, as Cage put it in the Emma Lake diary, “No tundra, nevertheless a northern sense of heightened well-being.”

Of course, the composer was also inspired by other cultures. He famously used the I Ching, a Chinese text, to generate music partly composed by chance. But it was in Canada that Cage, a lifelong critic of mainstream American society, felt free to premiere some of his most ambitious, career-defining works, including his most explicitly political piece. “I think he felt that the new music scene here was much more open and giving in those days than it was many places in the States,” says Larry Lake, a longtime technical advisor. Canada helped free Cage’s music from convention and control.

On a Thursday night in August 1961, Cage took the podium at Montreal’s Théâtre de la Comédie-Canadienne and moved his arms in a circle, imitating the hands of a clock. In response, eighteen musicians began to play. The piece, called Atlas Eclipticalis, was Cage’s first Canadian premiere, and he had written it by matching notes to star positions in an astronomical atlas. At the time, the whole world had its eyes on the stars; earlier that spring, a Soviet cosmonaut had beaten the Americans to space. Composing music with the help of astronomy was still an eccentric method, though, and one that marked an important shift in Cage’s career. After Atlas Eclipticalis, Cage moved away from writing music with notes, rests and other conventional symbols. Instead, he went on to create graphic scores—essentially, drawn music—and write textual instructions. He started to see himself as a creator of experiences through sound, rather than a composer of music.

This method led to 1962’s 0’00”. That work’s score is just an instruction: “In a situation provided with maximum amplification (no feedback), perform a disciplined action.” The musician can do nearly anything. The piece is also known as 4’33” No. 2, in reference to Cage’s best-known composition, 4’33”. When 4’33” is performed, the musician is silent; nothing happens. The near-universal response to the piece is: how is that music? But the score doesn’t actually ask for silence. It asks the performer to avoid making intentional sounds—with the goal of highlighting the impossibility of that task. In a concert hall, people are waiting to listen. So they do. Inevitably, there’s ambient noise.

These “silent” pieces culminated in Reunion, a work Cage premiered at Toronto’s Ryerson Theatre in 1968. During the five-hour-long performance, TV screens showing videos of Marshall McLuhan surrounded the audience; onstage, Cage and Marcel Duchamp played chess. Chess is typically a silent game, but the room was filled with sounds: as the two men made their moves, they triggered electronic samples.

In this way, Cage showcased his most famous concept: freeing music from itself. He had already set out this idea in his first book, 1961’s Silence. “The use of noise to make music will continue and increase until we reach a music produced through the aid of electrical instruments, which will make available for musical purposes any and all sounds that can be heard,” he wrote. “Whereas, in the past, the point of disagreement has been between dissonance and consonance, it will be, in the immediate future, between noise and so-called musical sounds.”

With his three silent pieces, as with Variations VI, Cage tried to draw attention to the unexpected. He wanted to provide opportunities for people to change their minds about what they thought were no-brainers: that silence isn’t noise, that noise isn’t music, that a chessboard isn’t a musical instrument. As he once said in an interview, he wanted to “show that something that is not music is music.”

Edmonton-born Marshall McLuhan, whose image Cage broadcast during Reunion, happened to be a friend of the composer’s. They had met in 1965 following a few months of exchanging letters. “For several years now, your work is in my mind and entering into what I do and think,” Cage initially wrote. It wasn’t surprising that the first man to write musical scores for electronics was bewitched by the herald of the information age. Though McLuhan was only a year older than Cage, the composer nevertheless saw him as a mentor. “It was like striking flint against a piece of metal,” McLuhan’s son Eric says. “When they got together, they sparked ideas.”

Like Cage, McLuhan thought that artists opened eyes. An artist should help people “notice what the conditions are in which they live and try to work,” Eric says of his father’s ideas. “In other words, pay attention to all the things that they are accustomed to ignoring.” The two men also shared the conviction that “the medium is the message,” a concept McLuhan had famously unpacked in 1964’s Understanding Media. This was in line with Cage’s thinking: he hoped that his music’s meaning would arise from the very act of experiencing it, of being shocked and confused. McLuhan lent Cage the academic theory (and bombastic epigrams) to back up his beliefs.

Cage gushed about McLuhan in the Toronto Star; the Globe and Mail referred to Cage as the “Musical McLuhan.” But perhaps McLuhan’s biggest influence on Cage came in the form of a suggestion for a new work, one that would confound the composer for years, and that eventually evolved into two of his most important Canadian premieres.

From the start, McLuhan and Cage had bonded over their love of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake. Not surprisingly, it’s a confusing, esoteric text. Cage had first read it serialized as a teenager in Paris, where he’d run away to be a writer after dropping out of university. McLuhan was working on a book that argued that the “thunders”—ten hundred-letter words—in Finnegans Wake described the evolution of human technology. McLuhan suggested that Cage write a piece of music featuring the text of the thunders. The epic work would be called Atlas Borealis with Ten Thunderclaps, and it would be a sonic torrent, blending the words with recordings of actual storms and electronic sounds. Like Atlas Eclipticalis, it would be written with a star map.

In the fall of 1967, McLuhan moved to New York, where Cage lived, for a year. Cage began to say that he was “studying with” McLuhan. He also told the University of Illinois that he’d submit Atlas Borealis for its centennial commission. But in November, McLuhan underwent brain surgery to remove a tumour. It was, at the time, the longest neurological operation ever performed. He suffered extreme pain and memory loss, and visits between the two men temporarily grew less frequent. Atlas Borealis slowed down, too; Cage didn’t complete the work in time for the Illinois commission. But McLuhan’s and Cage’s thinking continued to overlap. McLuhan’s surgery had made him hypersensitive to noises that one would normally ignore. “We’d be walking down the street and he’d stop and say, ‘Did you hear that?’” says Rosenboom. “He’d notice every change in the soundscape.” In effect, McLuhan was forced to live inside Cage’s philosophy.

In late 1975, James Rosenberger was at the CBC Radio building in Toronto, where he encountered “this rather friendly man” in the washroom. “We got out to the hallway and he asked me what I was there for,” Rosenberger recalls. “I said, ‘I’m here to audition for a piece for John Cage.’ He goes, ‘Well, I’m John Cage.’ I’m like, ‘Okay, do I get the part?’”

Rosenberger had answered an audition call for American men living in Canada. A new piece, Lecture on the Weather, which drew on many aspects of Atlas Borealis, would feature those men reciting excerpts from Henry David Thoreau’s writings, including Walden and Essay on Civil Disobedience. Speakers would blast recorded thunderstorms as projections of Thoreau’s manuscripts flashed in imitation of lightning. The CBC had commissioned the work to mark the American bicentennial, and Cage wanted sensory overload.

Wearing the same scruffy black outfit at each rehearsal, unshaven and chain-smoking, he hovered over the proceedings. After receiving directions from Cage, a technician, astounded, asked, “You want me to run how many channels of sound?” CBC Radio premiered Lecture on the Weather on June 15, 1976, and replayed it on Independence Day. “It was unlike anything that ever had been heard of,” Rosenberger says.

The CBC had wanted an American reference point and suggested Benjamin Franklin, but Cage picked Thoreau. In an introduction to the work, Cage linked the writer to his own ideas about silence: “Music, [Thoreau] said, is continuous; only listening is intermittent.” Elsewhere, Cage compared Thoreau and McLuhan. “In [McLuhan’s] writings I like the way he leaps from one paragraph to the next without transition,” he wrote. “This also happens in the Journal of Henry David Thoreau. Each one leaves space in his work in which a reader, stimulated, can do his or her own thinking.”

Here again was Cage’s fascination with quietness and free thought. Although Lecture on the Weather was supposed to commemorate the Declaration of Independence, Cage clearly wasn’t interested in patriotism. Before the broadcast, he told listeners that, as a child, he wrote a speech that “proposed silence on the part of the U.S.A.,” which he read at the Hollywood Bowl after winning a contest. “One of the greatest blessings that the United States could receive in the near future would be to have her industries halted, her business discontinued, her people speechless,” he had written. “We should be hushed and silent, and we should have the opportunity to learn what other people think.”

In 4’33”, 0’00” and Reunion, Cage’s theory of silence posited that listeners should notice what they’d previously ignored. With Lecture, Cage politicized this idea. Thoreau wrote Civil Disobedience to protest slavery and US imperialism, and Cage used Lecture to plead for Americans to rethink the entire system upon which their country was built.

The CBC prompted Cage to create his most overtly political piece of music. He seemed to believe that only a Canadian broadcaster and audience would accept such a work, and he said, of the Lecture commission, “Since it came from Canada, I accepted immediately.”

Cage wanted his art to make a difference. In Canada, he felt liberated to use music to promote social change. “If art were more socially effective,” he said, “then it could be the pleasing alternative to holocaust. It could persuade people (all of them) to change their minds.”

In January 1982, Cage arrived in Toronto for the first fully staged production of Roaratorio, a work he originally composed for West German radio in 1978. Though McLuhan had died two years earlier and never got to see it, Roaratorio is a tribute to the theorist, and it features all the elements of Atlas Borealis, the unfinished work that McLuhan and Cage once dreamt up. In the live performance of Roaratorio, voices chant excerpts from Finnegans Wake over a dizzying, sixty-four-track mesh of sounds mentioned in the book, including thunderstorms, crying babies, car horns and birdsong.

It is an encyclopedic soundscape of everyday life, and the most bewilderingly comprehensive work that Cage ever wrote. “The oratorio is in the church; but the roaratorio is everything outside the church,” he said. Roaratorio is a musical recreation of the chaos of everyday life; such disorder represents the ultimate freedom from control. Cage hoped that Roaratorio would open listeners to the “poetry and chaos” of Finnegans Wake. Most people can hear the chaos in his music. The trick is to hear the poetry.

Why did Cage write such challenging music? It’s a common question, and the answer can be found in the compositions themselves. Chaos creates open ears, open eyes, open hearts. In 1981, he told Toronto journalist Michael Schulman much the same thing: “Music can open the mind to things which it wasn’t certain that it liked,” he said. “Being pleasing is the exact opposite of changing and of revolution.”

From 4’33” to Roaratorio and beyond, Cage tried to convince listeners to simply listen. And, whether in the form of a strange new landscape, a pacifist attitude or an innovative mentor and friend, Cage often found the inspiration to do so in Canada. He came here until the end of his life. There were performances, interviews, recordings; he traveled from Montreal to Vancouver.

Cage never stopped working toward revolution through music, and he kept up his Canadian connections until the end. In the summer of 1992, only one month before Cage died of a stroke, Robert Aitken, a friend and the director of New Music Concerts in Toronto, offered to commission a work. Cage was still in high demand, but he wanted to make room in his schedule. He wrote to Aitken:

So good to hear from you. I don’t know what to suggest unless it be that I write a new piece for you. Circumstances alone have kept me from doing that in recent years. Now it seems possible…

As ever,

John