Properties of The Past: Interview with Rutu Modan

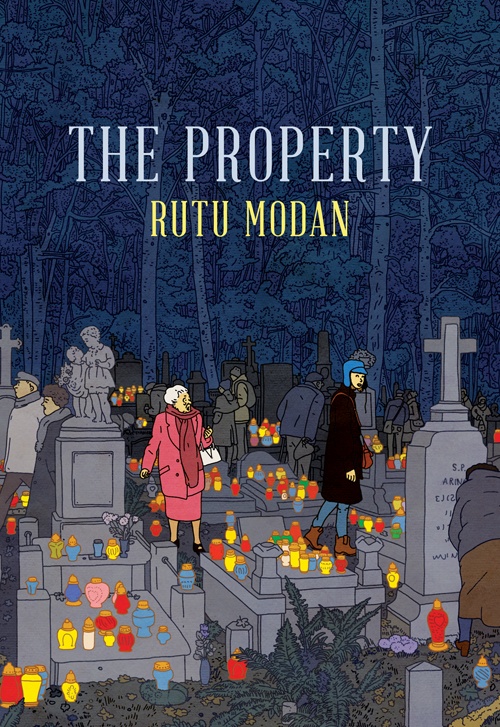

Comic book artist Rutu Modan on the influence of family and history in her new work, The Property.

For comic book artist Rutu Modan, creating characters involves as much action as thought. The Israeli artist has long asked friends to act out panels from her meticulously planned storyboards. “I like to use body language in my characters,” she says. “Each character has his own way of moving.” For her latest novel, The Property (Drawn & Quarterly), she hired actors to stage scenes from the tale, of family dynamics and historical scars, in her apartment. “We were like kids, playing an imaginary game,” She says. Modan’s process may be unique, but to the actors it seemed natural. “What do they know about comics? They thought, This is how comics are done."

Modan is a reliable source on the medium: she’s been drawing comics since she was five. The Property is her second solo graphic novel, and the book evolved out of a series she created for the New York Times website. Two columns, one each, were inspired by her grandmothers. From there, she developed the story of Mica, a young woman who has just lost her father and is accompanying her grandmother Regina from Israel to her former home in Warsaw to take back the family’s old apartment. While Mica is eager to help Regina reclaim what is rightfully hers, Regina’s feelings about returning to Poland are more complicated. Modan renders her ambivalence in expert strokes of elderly crankiness. But there’s more to Regina’s resistance than Mica realizes.

The Property depicts lost-in-translation moments between a new generation of Israeli young people and the generation of the “big war.” “Suddenly, there’s this nostalgia for Poland,” says Modan. “Because of the stories they’ve heard from their parents, how wonderful it was, how rich we were, maybe. It was not always true, but this is part of thinking about the past.” This has led to a conversation in Israel about the property lost in the war. Modan explains that young people think treasures wait for them in Poland, or, as in The Property, at least some anemic form of justice for the suffering of their elders. Mica longs to reclaim her grandmother’s apartment because she feels Regina deserves to get it back. But, as Modan explains, reclaiming what was lost is complicated not only by trauma but bureaucracy.

During the war, the city was destroyed by bombs. “If you look at a photo from ’45 of Warsaw, you see a desert,” Modan says. The communists moved in and rebuilt. Property was nationalized. After the fall of the Soviet Union, people who had fled other parts of Poland began to slowly reclaim what had been taken from them when they were forced into ghettos and concentration camps. But in Warsaw, ex-pats had to not only have proof of ownership, but also proof that they had made an attempt to get their property back before 1948. “People who went to the Ghetto didn’t always keep papers. Most of the archives were burned down,” Modan says. “If you think about the survivors, they were fighting to create new lives, to build a life from the ruins. So to find a letter that they wrote, it’s possible, but...” She trails off.

This history and the resulting family dynamics influence The Property in equal measure. Mica and Regina’s familiarity and fights are as intertwined as a strand of DNA. They’re shadowed on their trip by a frustrating family friend, claiming to be in Warsaw for a conference. “He’s based on my uncle, who’s a very nice and very irritating person,” Modan says. Both women find romantic foils in the city, and Mica’s Polish paramour is inspired by a combination of Modan’s husband and herself.

When I ask Modan—who says she can tell me so much about property reclamation in Poland that she could be a lawyer—whether it was the familial or historical elements that interested her more about writing this story, she says, “It’s not one thing. Family relations are always part of my stories, that’s my life. And family’s not always easy to have. I was interested in how history influenced a life, or mostly this generation, the generation of the big war.” There’s a unique narrative here, the story of people who have experienced something they could probably never begin to describe to those who came after. “Their lives suddenly went in a different direction than they planned, due to history,” she says. “And I was interested in the way we deal with the past.”