Production still by Matt Johnson.

Production still by Matt Johnson.

We Need to Talk About Matt

A new film charts one boy’s transformation from pop-culture nerd to delusional murderer.

HIGH-SCHOOL STUDENTS Matt (Matt

Johnson) and Owen (Owen Williams)

are testing out new wireless mics in

the park when they run into two fellow filmmakers. After the pair, who

look about eight years old, describe

their British murder mystery, Matt

launches into a rapid, almost rabid

pitch of his own. “Our movie is about

two students in school who get bul-

lied by this gang called the Dirties.

And so they decide to get revenge on

them by—”

“Killing them?!” The boy interrupts Matt, grinning. It’s more of a statement than a question. The film must somehow end with violence.

Matt’s elaborate monologue describing the film-within-a-film that anchors The Dirties (XYZ Films) is peppered with references to The Usual Suspects, Irreversible and other films these kids would never have seen. The moment deftly introduces a pop-culture-obsessed savant protagonist who is ostensibly working on a school project. Yet Matt’s film is less a homework assignment than a fictional revenge fantasy against the real-life Dirties, a gang of bullies he faces at school. And like this film-within-a- film, the feature debut from Toronto- based director Matt Johnson blurs the lines between real and imagined. Using “found footage” to offer disturb- ing insight into the world it inhabits, The Dirties is a nuanced entry into the debate surrounding the media’s killer influence.

When the kids hand him a copy of their own movie script and leave, bikes in tow, Matt tells his best friend Owen that the boys are essentially younger versions of themselves. He jokes that they should have told the children that it gets better. He laughs, a twinge of bitterness discernible in his voice. “We should have just straight-up lied to them.”

Johnson plays a loserish, adolescent version of himself who, through his school project, achieves a modicum of self-actualization and control by constantly appropriating the dismal reality in front of him. The Dirties explores how, despite this outlet or possibly because of it, Johnson’s natural personality becomes a death trap and Matt’s grip on reality begins to give.

With their boyish looks, Johnson and Williams could pass for high- school students. And they did—to make the film, the twentysomethings enrolled in a Peterborough, Ontario high school after obtaining permission to shoot scenes in classrooms and hallways. The students, many of them caught on-camera, believed Matt and Owen were simply new kids making a film project. Though they hired actors to play the characters, The Dirties contains a realism that is largely lacking in modern found-footage films.

Traditionally, films using this technique employ a suspension-of-disbelief formula: the film you are watching consists of found footage from a video camera that has been edited together into a narrative. However, the slick production quality of films like Paranormal Activity has turned the original idea stale. That’s why The Dirties, with its hybrid combination of documentary and drama, feels original and compelling by contrast. When two of the Dirties hit Owen in the head with a rock, for example, Johnson shows only the immediate aftermath, with the camera spinning between the two bullies running down the street and Owen on the ground, clutching his head. Throughout the film, the viewer is never certain what, if anything, has been staged. In this particular scene, the bullies’ random act of vio- lence was orchestrated, but it’s hard to tell if a concerned witness nearby is an extra or a real bystander. In the scene in the park, Johnson and Williams happened to run across the two kids by chance—they were not anticipating meeting the eight-year-old versions of their fictional characters. But the unplanned scene fits perfectly with the film’s themes. That this real kid so quickly surmises the ultimate conclusion of Matt’s film is especially striking: he embodies exactly the kind of hyper-imaginative head space that can make one prone to losing grip on reality.

While Matt’s character is possessed of this same manic energy, he remains reticent in his encounters with his antagonists. The boys refuse to respond to the Dirties and provoke an escalation. Their defeatist stance is necessary—the last thing either of them wants is to be further embarrassed or injured—and it is also the catalyst for their artistic expression. Instead of wallowing, Matt and Owen turn to filmmaking as a way to survive their tribulations. The two disappear into a boy-cave plastered wall-to-wall with movie posters and decked out with action figures. Two of the posters are close-ups of Adam Brody and Benjamin McKenzie, who played best friends on the early-2000s prime-time soap The O.C. But their names are no longer visible, replaced instead with Matt’s and Owen’s. This subtle addition is indicative of Matt’s tendency to mediate his own existence within the sphere of celebrities and fictional characters. The boys’ departure from reality safeguards them from the threatening corridors they must traverse every day.

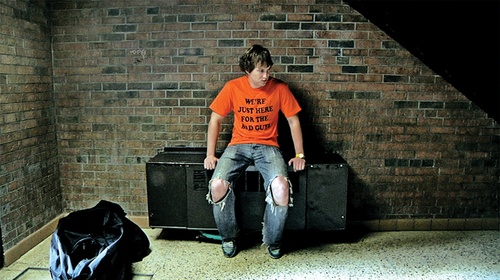

This departure foreshadows Matt’s eventual suggestion to Owen that they make their own fantasy a reality: take down the bullies at school with guns and film the process. It’s a joke born of frustration, a way for Matt to blow off steam after Owen is hit with the rock. “We can wear shirts that say, ‘We’re just here for the bad guys,’” Matt exclaims as he wipes down a whiteboard to jot down ideas for what he calls The Dirties II.

Matt’s transformation from pop-culture nerd to delusional monster is gradual, but the film ends the only way it can: a heavily armed Matt begins to take down a few bullies in a hallway, then encounters a locked-in Owen. This strange, brief encounter between the two is surreal and depressing. Owen no longer recognizes his best friend, yet Matt looks and sounds exactly the same.

By the time Matt has begun making his film about a real school shooting, he has completely disappeared inside his fictional universe, and there is no escape. Herein lies the most salient argument in The Dirties: this transformation does not happen overnight, but after years of cumulative abuse and neglect. The Dirties argues that media-related violence is also a product of cumulative viewing: it’s not a single movie or video game that triggers a troubled kid to commit homicide, but a lifetime of watching mediated murder. That kind of exposure is unavoidable given the ubiquitous nature of popular culture. What is also unavoidable, and entirely human, is the brain’s ability to imagine. “Crazy technically means when you lose your ability to tell the difference between your thoughts and reality,” Matt’s mum tells him the night before he shoots the Dirties. Her uncannily astute description feels frightening for the viewer, but, naturally, is only amusing to Matt.