The Impossibility of the Young-Girl

Hilton Als, Tiqqun and the lost children of consumerism.

Who is the “White Girl”? On the internet, she’s the butt of a lot of jokes: she is spoiled, bratty, a lover of Starbucks, Uggs, and Lulu Lemon. She is lazy and entitled, she is loud and theatrical, educated perhaps, but not very smart. Cluelessly racist, too, as she appropriates not only twerking but words like ghetto and ratchet as well, to show that she’s down with a culture she finds edgier than hers, or as she goes to “Africa” to help starving children. She appears in memes like Shit Girls Say, Shit Sorority Girls Say, Shit Single Girls Say, White Girl Problems and in hashtags on all your social fora – it goes on and on forever in countless representations of the artlessness of contemporary North American middle class.

There is not much to love about this person, who is drawn with disdain in Tiqqun’s Preliminary Materials for a Theory of the Young-Girl. The book, which came out in English in the spring of 2013, is a fragmented critique of a model of personhood native to late capitalism, where the consumer is the perfect citizen and where no real relationships are possible. The Young-Girl shops and fucks with equal detachment. The revolutionary collective is careful to assert that the Young-Girl is not necessarily young, or a woman—a handful of men, among them Silvio Berlusconi, are included in the book as examples of Young-Girls. Neither is she explicitly racialized, but the quotes from women’s magazines (“DON’T TOUCH MY BAG!”; “AT TWELVE YEARS OLD, I DECIDED TO BE BEAUTIFUL.”; “TOO CUTE!”) with which the book is sprinkled have a very distinct echo of the catchphrases of the White Girl on the internet. They are essentially the same person, approached with different attitudes. If the memes go for a direct type of humour where the appearance of the Girl is enough to provoke eye rolls and chuckles, Tiqqun take three steps back for critical distance. But their voice is a snarl, and the text, which in essence diagnoses a symptom of capitalism, is laced with contempt. Tiqqun hate these hopelessly superficial and stupidly self-interested bitches who go through life with no other goals beyond seduction and consumption.

Their hatred is so close to good old familiar misogyny that it undermines their disclaimer that the Young-Girl is not a gendered concept. This was widely noted in the debate that followed its English-language publication, and prompted many to ask whether the rehashed complaints about the stupidity of girls enthralled by beauty, shopping, and dating were not hatred squandered on the wrong target. In the words of Nina Power, “Behind every Young-Girl’s arse hides a bunch of rich white men: the task is surely not, then, to destroy the Young-Girl, but to destroy the system that makes her, and makes her so unhappy, whoever ‘she’ is.”

All these jokes about White Girl Problems are so staid. We all know they exist, and how sad/annoying/laughable/limiting, depending on your viewpoint, this model of life is. Sometimes, like Franchesca Ramsey’s Shit White Girls Say to Black Girls, these jokes manage to open up a space for conversation that might take us somewhere new. But that is rare: most often the snarl and the punch line merely repeats a depressing fact, and won’t help the Young-Girl or anyone else to see beyond that model of life. And what an impossible, limited life it is—on that point, Tiqqun are right. Sarah Gram writes wonderfully about the Young-Girl: if her body “is her primary commodity, her ticket of entry into the world of consumer capitalism (outside of which she is not only useless but also illegible), then her ability to authentically maintain the femininity of her body maintains its value.” The product of this work is her image, broadcasted IRL and in selfies. It’s an image that “may assert sexual subordination, but it still asserts,” writes Gram. This is essentially the only position available to her, and it is a position where she is constantly watched. With so many eyes on her, the Young-Girl must labour relentlessly to maintain herself, to produce a persona and a body palatable to those she seeks to (those she must, for her own survival) seduce. So much work is required to have beautiful skin and the right kind of attractive body.

Sure, you might call this frivolous, say that it fortifies infatuations with luxury and image, and that it props up stultifying ideas of what people should be, when really we could use a couple of more bodies in the more important work of overthrowing a corrupt system. There are millions of inequalities to rectify! But this is essentially the only position comfortably available to her, and therefore, recognizing that work is key to understanding the impossibility of the position of the Young-Girl.

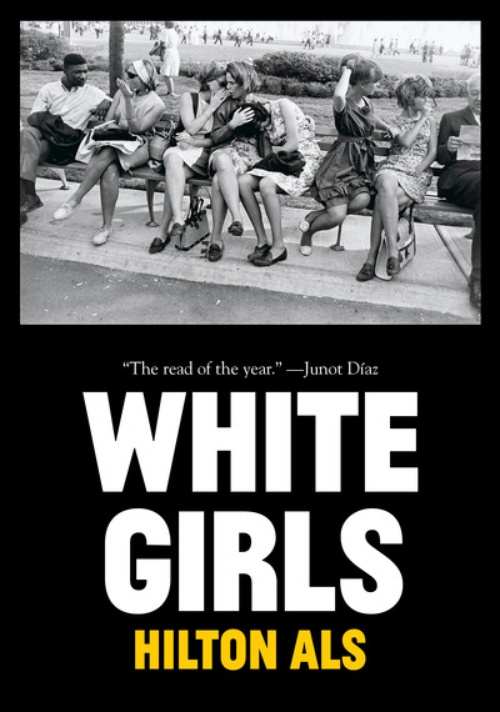

For Hilton Als, the New Yorker’s theatre critic and most recently the author of the essay collection White Girls, this work is performed in the crossroads of several forms of oppression, squeezing the White Girl from so many directions that it might ruin her, and those accompanying her within that crossroads, too. Just as Tiqqun’s Young-Girl is not necessarily young, or a girl, Als’s White Girl is not necessarily white, or a girl. The essays that make up the book circle around White Girls, and in some cases those attached to them through something like love, and only about a third of them are actually white, and girls.

One of them is Louise Brooks. One of the first movie icons, she was revered for her striking style – that black helmet of hair – until she dropped out and left the scene altogether, sick of the constant pressure from the gaze of others. She was “the product of someone else’s dream” for so many years, a star often derided for her acting although, Als suggests, she was in fact before her time. When she is remembered today, it is often for her looks; many of her films have been lost. But her beauty captured and fascinated people, who coveted her for it, wanted to own her. And for a while, Als theorizes while writing in Louise Brooks’s voice with wonderful compassion and respect, this is what she wanted too. She is “Louise Brooks, whom no man will ever possess,” but in letting others think that they could, as they directed or choreographed or loved her, she was propelled forward in life without having to do much herself. This passivity became a way of obliterating herself, something she had wished to do ever since a neighbour sexually abused her when she was a child. “My beauty was a conduit for violence against me,” Als-as-Brooks writes. Until she couldn’t stand this either, and then she simply abdicated everything. When “you drop out you’re not so much bottoming out but rising: above the mundane, above being anyone’s wife” – she drank, she worked for a while as a call girl and as a department store clerk, she was supported by a former lover. She wrote, she read.

She may look much more interesting to us—more sophisticated in her style, certainly—than the Young-Girls of the 21st century, but isn’t this the way people understood her? In the public’s eye she was heavily reliant on her looks to get roles, she slept with so many women and men, but by her own admission loved but one of them. Tiqqun: “The Young-Girl is the commodity that insists on being consumed, at every instant, because at every instant she becomes more obsolete.”

Until she drops out, stops caring altogether, realizing that consumption is nobody’s saviour in the long run. For Louise Brooks, dropping out didn’t change the framework of how the world saw her, but it freed her, as much as she could be freed, at least from the pressure of trying to live up to those expectations connected to the desires of others. Reading Als’ essay on her makes one think of Britney Spears shaving her head, of Lindsay Lohan’s multi-year long public unravelling.

Als writes about Richard Pryor, immensely successful as a comedian but always pegged as a black man, always joking as a black man because how could he not? Even if he wanted to do something else, be perhaps not something else but at least something more than what the audience thought his skin colour meant, he was always defined in the eyes of the audience as a black man only and because of that also to himself. Als writes about how Pryor tried to fit into that one narrow slot opened to him with the aid of drugs and drinks and often troubled relationships with white women. (“There is a bond in oppression, certainly, but also a rift because of it—a contempt for the other who marks you as different—which explains why interracial romance is so often informed by violence.”) Als writes about a fictive sister of Pryor, who writes like hellfire but refuses to play along; she, too, drops out, imagines Als, despising her brother’s funny dances. He writes about Eminem, born in a Detroit of horrible inequalities, miles away from the lineage of the wealthy whites, yet decisively not black, and the pain and the rage of his difficult childhood in the care of a mother who held him too close, took him as a “husband” because she had none of her own and was too young to be her own person, and the rage of not fitting into a given category. Als writes about Louise Little, the mother of Malcolm X, all but erased from public consciousness because she, easily passing as white, and a woman too, doesn’t fit the narrative of the black freedom fighter, and because Malcolm X himself despised her, partly, if not fully, for these facts. And he writes about Michael Jackson, who could only make music that mattered before he had changed into his “now-famous mask of white skin and red lips (a mask that distanced him from blackness just as his sexuality distanced him from blacks),” after that, estranged from himself, all he could do was to recreate the formula of his earlier years, having lost his own self by trying too hard to fit the slot opened up to him by people’s expectations.

And he writes about André Leon Talley, best known as Vogue’s editor-at-large and a White Girl if there ever was one. Although he is more sophisticated in the language of appearances than most Young-Girls, many of his tweets could be seamlessly inserted into Preliminary Materials: “Splash, Dash, and Dazzle. Put those words in your vocabulary and your life. Be Dashing. Dazzle your world. Splash through wit and humor!” Als portrays him in all his absurdity and grandness, and just as we are meant to laugh at the White Girl-memes, or scoff at the Young-Girl, it would be very easy to make us laugh at Talley. He made a name of himself in New York’s fashion world, Als writes, for “insisting, at his local post office, on the most beautiful current stamps and holding up the line until they materialized; serving as a personal shopper for Miles Davis at the request of Davis’s companion, Cicely Tyson; answering the telephone at Andy Warhol’s Interview, in his capacity as a receptionist, with a jaunty ‘Bonjour!’ and taking down messages in purple ink (for bad news) and gold (good news); […]; overspending on clothes and furnishings and running up personal debts in his habitual effort to live up to the grand amalgamation of his three names.”

But instead of laughing at Talley, Als sees and describes the pain he must endure, the racist jokes and daily disappointments he must forgive and forget in order to maintain his belief in opulence. Moreover, he shows how all the wrongs he must put up with also create a desire for belonging in that world of opulence. It’s an impossible double bind.

André Leon Talley was born in Durham, North Carolina, fifteen years before the end of Jim Crow. No one in his family understood his interest in fashion, or why he kept travelling to the white section of the city to buy Vogue. For Talley, fashion was a kind refuge, “so opulently kind;” the pictures in the glossy magazine were a dream of a beautiful, more glamourous world. In the words of sociologist Werner Sombart, fashion is capitalism's favourite child," and in a capitalist system, submerging oneself in fashion can be a way of floating downstream. As long as the images are powerful enough to let one forget the world outside, this mode is more comfortable than fighting to swim in another direction. It is especially attractive for someone with an acute sense of aesthetics and beauty, who finds little of that in his immediate surroundings.

And Talley, hungry for something kinder than what he saw around him, modelled himself into a man of that world. Having accomplished this feat, he in turn became the site of the dream projections of others. Als describes the reaction of a black drag queen who recognizes Talley as he enters a nude cabaret with John Galliano: “That’s what I want you to make me feel like, baby, a white woman. A white woman who’s getting out of your Mercedes-Benz and going into Gucci to buy me some new drawers because you wrecked them. Just fabulous.” Galliano is white, Talley is not, but it is the latter who is the White Girl in this scene. Galliano is “rather like another accessory.” In Als, as in Tiqqun, anyone who is fabulous and privileged enough to pose as careless in matters of looks and finance fits the bill. Als asks, in another essay: “How could one be a white girl and hate it? Wasn’t she—whoever she was—everything the world saw and wanted?”

Sure, there is a certain power in being desired, which explains the draw of being, and even being near, a White Girl/Young-Girl. But the power yielded in this position is highly limited. The Young-Girl remains the object, circumscribed by rules of attraction that she didn’t write but is nevertheless beholden to in order to maintain her value. Hilton Als describes both the draw and the impossibility of this position with incredible acuity, as well as the forces that lie behind this crossroads of pressure.

But despite the pain that he describes so perfectly in these stories, Als has little patience for victimization. The longest essay in the book, “Tristes Tropiques”, meanders around Als’s relationship with SL, a black, mostly straight man, whom Als loves, and who loves Als, although SL’s romantic relationships are mostly with white women. Their relationship is large, incredibly important, deep, and intimate, but not in the way you first think. In talking about it, Als rejects all prior narratives of black experiences in a racist world, queer experiences in a world violently afraid of anything that can’t be easily categorized. He writes, “There was no context for [others] to understand us, other than their fear and incomprehension in the presence of two coloured men who were together and not lovers, not bums, not mad.” Others tried, through subtle glances and not so subtle advice, to turn them into something more easily legible and manageable, but although no one is impermeable to the opinions of others, fear ultimately couldn’t separate them. Every time SL and Als were together, he writes, “I wanted to house myself in SL’s thinking. It was so big and well-lit, like a large house sitting solid on the bank of a river.” In this house, they told stories that were their own completely.

I imagine that they, through their stories, write a different kind of narrative for themselves, a world less burdened by preconceptions—this is what Als does in his book. He sets all his subjects free of the prison that is victimization, all the while retaining a sharp understanding of what wrecks them, and how all these paths of destruction are interconnected. And in doing this, he opens up a space for roomier subjectivities that aren’t constricted by the demanding and suffocating ideals of late capitalism. When Als uses words like husband, wife, woman, white, he explodes them to mean a certain power position, which changes in force depending on who else is present. This is what Tiqqun claims to do when they write that the Young-Girl is “obviously not” a gendered concept. Instead of explicitly asserting the same thing, Als, through his writing, performs an opening of these subject positions.

And he does it so much better, because his compassion enables him to understand the forces that lie behind these ways of being, not just their superficial forms. It would be ridiculous to attempt to do it without recognizing the crushing realities that burden the Young-Girl/White Girl, or privilege and the harm that she, too, can do to others. Als knows all this – often, his book brings tears to angry eyes. But the true magic lies in how he goes beyond these hardships and lets us glimpse a different way of being. “Sitting on the subway, the lights go by but the people don’t. Standing above me and around me I see how we are all the same, that none of us are white women or black men; rather, we’re a series of mouths, and that every mouth needs filling: with something wet or dry, like love, or unfamiliar and savory, like love.” A book can’t abolish material inequalities, but in terms of ideas, Als offers something new, a vague, powerfully malleable dream to break all of us free.