Photograph by Julia Cervantes.

Photograph by Julia Cervantes.

Review: Untitled Feminist Show

Young Jean Lee bucks our expectations to turn sincerity into an effective weapon.

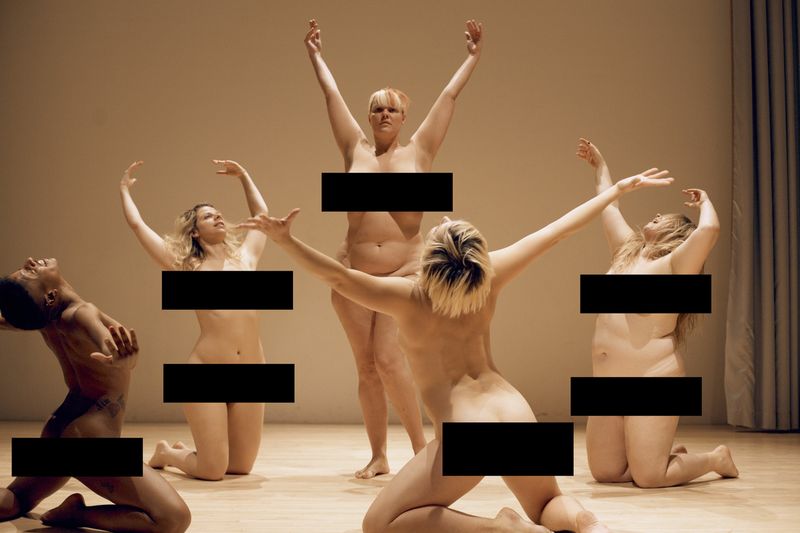

You are post-gender—so are we. This is the phrase designed to brand the Canadian premiere of Young Jean Lee’s Untitled Feminist Show, accompanying a photo of the performers in “costume”: wholly au naturel, save for the censor bars across each chest and crotch. Throughout the program are promotional shots of a utopia in champagne-pink, where six women have taken hands as if to form a frozen ring-around-the-rosie arrangement lifted from Matisse’s Danse.

The play itself began more abruptly—house lights up, no emblematic overture playing, no sympathetic attempt to ease us in. Without warning, behind me came the heavy synchronized breathing of a trio of strangely solemn, thoroughly naked women. Still more nudes joined from the wings to form, at centre stage, that same image from Matisse, lifted off the canvas into a living picture. Turns out that Danse is weirder in real life. A techno mix filled the theatre to break the overhanging severity into a party made up of idiosyncratic combos of ass shakes and struts.

UFS is the latest turn of this dialectical screw for Young Jean Lee. By limiting her ironic repertoire and embracing the fanciful, hopeful and so “un-cool,” she has again bucked our expectations so as to convert flowerpower sincerity into the most effective weapon against the ironist, whether that irony is racist, sexist, or otherwise.

For a woman lauded as the best downtown playwright of her generation, it’s remarkable that Young Jean Lee has been making plays for only ten years now. In 2003, after abandoning her PhD on King Lear, she joined Mac Wellman’s MFA at Brooklyn College, a kind of incubator for avant-garde playwrights. There, Wellman passed on a somewhat unorthodox aid for writer’s block: Write the worst play possible. To the point of cliché, almost all profiles on Lee pay respect to this edict as the reliable goad at every stage of her career. Whether the play concerns Wordsworth and Coleridge musing about early romantic poetics (The Appeal, 2004), or a sermon from surprisingly even-handed evangelical Christians (Church, 2007), we’re usually guaranteed the best worst conceit imaginable.

Starting around the mid-aughts Lee applied Wellman’s credo to the substance of identity politics, creating what we could call her “minority rage” cycle. Songs of the Dragons Flying to Heaven (2006) features quick cartoonish scenes where Asian women in kimonos commit seppuku, alternate their speech between three East Asian languages and preach feminine docility; The Shipment (2008)repeats the formula forblack actors as they perform a minstrel show, deal drugs, rap, play basketball and kill each other. Lee has a forthcoming play titled Straight White Men. In Songs, a character named “Korean American” explains minority rage somewhat tongue-in-cheek: “There is a minority rage burning inside me ... I hate white people and this is why. I hate white people because all minorities secretly hate them. If you think your best friend is black, then think again because your best black friend hates your guts!” This matter-of-fact assault on the audience wasn’t new material for Lee—Church (2007)featured many accusations of “masturbation rage,” Pullman, WA (2003)has characters come up and tell you how uniquely worthless you are—and yet, there was a strangely confrontational ironic-sincere seesaw in these new shows that tapped into audiences’ latent and thoroughly contemporary racism. (Think the refrain: “I don’t judge people by skin color; they’re all just people to me.”) It was in these plays that Lee offered a double-edged way of dealing with exactly this species of “so not racist.”

This famously vituperative approach is part of the reason why Untitled Feminist Show was such an unexpected aesthetic about-face for Lee, with its Kumbaya atmosphere. Bereft of language, and armed solely with frilly pink parasols, UFS is a winsome and wistful hour. Just where was the invective against the pampered people who colonize her opera boxes and parterres? Lee herself has expressed unease with “preaching to the choir” by touring a show not as baldly provocative or difficult as her previous work. Rather than haranguing us with a scattershot of distasteful caricatures or a thesis of honed political invective, she strove to make something “inspiring or uplifting.”

In San Francisco, everyone apparently treated the playlike a big party. Not so much in Toronto—as far as I could see, from the moment those women first came down panting behind us, the audience seemed divided into two broad camps. First, there were the nudity enthusiasts, nodding with over-appreciative zeal, beaming in anticipation of every punch line, as if performing laughter. Then there were the brow-furrowed conservatives who seemed perturbed at the idea that nudity, if it must be presented at all, would be done without coyness, elegance, or at least shame. I felt strangely caught in the middle—there was something about an unapologetic utopia that unnerved me, something too earnest in the presentation that I couldn’t fully access.

As in her older work, Lee organizes UFS in thematic vignettes—skits that range from a hip-hop routine of domestic duties to a lewd seduction scene played out by pantomiming hand, blow and rim jobs. There are two musical numbers, one in Welsh, understated and tender, the other a series of “La la la’s,” a gleeful assault on our ears. The cast features two professionally-trained dancers who lend the movement sequences a skillful grace, but it’s the amateurs that captivate our attention as an earnest celebration of dance for the sake of self-actualization.

It’s no surprise that many have made the connection between UFS and sixties performance art. For me, it recalled the Performance Group’s Dionysus in ’69. Reexamining the “initial impulses” behind the cultic rites in Euripides’ Bacchae, Dionysus featuredchorus members, semi-nude to nude, writhing on the floor, moaning in ecstasy and making out with the audience. As a relic of “free love,” the nudity in Dionysus isn’t half as shocking for contemporary viewers as its unchecked sincerity—their “make love not war” sentiment is valiant, if not overbearing. I felt similarly alienated at what was billed as the Living Theatre’s “last-ever” show in their Lower East Side home last spring. If you’re not familiar with Judith Malina and her revolutionary posse, a quick Google Image search shows the group spelling out the word Paradise with their naked bodies. At their tiny black box on Clinton Street I was made to skip around, greet and hug my fellow participants, cut and then lace my own footwear, all the while chanting “in the beautiful nonviolent anarchist revolution there will be no greed ... there will be no pain ... and we will all make our own shoes.”

This is all to say that, for me, UFS echoed these urges from the sixties. But in 2014 I wasn’t prepared for a nostalgic embrace of a certain idealism that my generation couldn’t possibly muster without winking. As a child of snark, I squirm at flowerpower vagaries. I want my politics self-aware and unforgivingly so.

So in Lee’s hedonist post-gender paradise, half the fun involves figuring out whether the actors are laughing or coming or both. As an insightful inversion of the male gaze, the play significantly reorients our ways of viewing and receiving women’s bodies on stage—sure, we’ve seen breasts before, but not so much ass-crack hair or the pirouettes of the obese. In these ways, UFS is a refreshing send-up of women in all their fleshy diversity. During a dance vignette where all the women giddily jiggle their bodies to maximum ripple effect, I caught myself mid-chortle—was I participating in some stigma of fatness? But weren’t the actors maybe inviting laughter? This is the kind of judgment—layered through the discomfort and uncertainty of taboo—that Lee induces to great effect.

The most gratifying moments in UFS were the passing instances of Lee’s signature rage. The apex occurred when one of the larger actresses, Jen Rosenblit, wound herself up, circling the stage as the house lights came up and metal music overwhelmed the theatre. Suddenly, Rosenblit careened into the audience, in a way native to the Jerry Springer Show, mounted the lap of an old woman in the audience, and once there, shook her breasts erratically while sweat whipped from her long dark hair, all over that woman and the people surrounding her. The look on the old woman’s face couldn’t have been more authentically terrified, as if she’d been violently assaulted.

Playwright Wallace Shawn spoke in his Paris Review interview about the paradoxes of writing “disturbing” work. Plays that attempt to withhold easy catharsis still prove to be thrilling, affecting, or even pleasant.

“In the sixties, there were plays inspired by the black power movement where a guy would come to the front of the stage and yell at the audience, ‘You are pigs, we are going to get you.’ And the drama critic would say, ‘My favorite part of the evening was the thrilling moment when that guy approached the audience and said ‘You are pigs. We are going to get you.’… To the writer of the play—well, he might have meant it. But the critic watching the play didn’t really feel threatened, he just thought it was great theater.”

What Shawn describes here is exactly what Lee is up against now that her usual diatribes have become fan favorites. She has to contend with assholes like me who are itching to get yelled at, tackled and sweated upon only to go home and tweet about it. But in serving up a feminist vision, Lee challenges us to contemplate for a moment an alternative future. And beyond a utopian experience, she has vexed her usual audience’s expectation by creating something bold and brave, and frankly—for some of us—harder to swallow in its idealism.

In Songs of The Dragons Flying to Heaven, the same Korean-American who defined minority rage brought us this incisive moment of meta-theatricality: “The truth is, if you’re a minority and you do super-racist stuff against yourself, then white people are all like, 'Oh you’re a cool minority' and they treat you like one of them.”