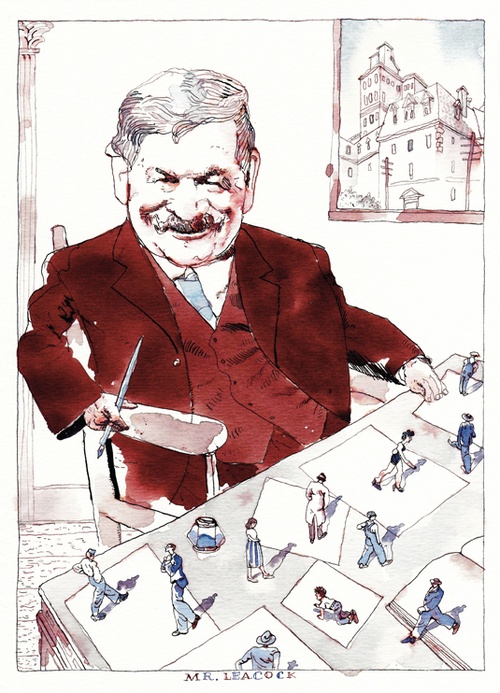

Illustration by Barry Blitt.

Illustration by Barry Blitt.

Sunless Sketches of a Sprawling City

Remembering Stephen Leacock, Canada's master ironist, one hundred years after the release of Arcadian Adventures with the Idle Rich.

THE ONLY PEOPLE who

speak Stephen Leacock’s name with any

regularity these days

are the Arts students

of McGill University,

many of whom flood

in and out of the giant, brutalist campus building bearing

his moniker with no idea of its significance. These accidental stewards of

his legacy may not know that Stephen

Leacock was a McGill professor, or that

he was more famous for writing humorous stories. Nor are they likely to

know that their city is the subject of his

most withering satire, an underappreciated masterpiece hitting its centenary

this year.

Although most of the people bustling through the Leacock Building today are happy to do so without ever wondering at its history, a few literature students might be fortunate enough to first read Stephen Leacock in the building named for him. I was one of them. In the same building, I also studied in the political science department that Professor Leacock once chaired. I suspect that he would be more proud of the former legacy than the latter. “Personally,” he once wrote, “I would sooner have written Alice in Wonderland than the whole Encyclopaedia Britannica.”

Leacock’s best-known work, Sunshine Sketches of a Little Town, is neither a surreal fairytale nor a reference book but a collection of short stories that epitomizes a gentle, sympathetic brand of caricature. But this year marks the hundredth anniversary of its sequel, Arcadian Adventures with the Idle Rich, set in a big city that rather strongly resembles Edwardian Montreal. Arcadian Adventures is marked by a darker streak of satire and social criticism aimed at the decadence and selfishness of the urban affluent class. Leacock loved Montreal—except when he hated it.

The two works, considered together, constitute a study in the classical distinction between Horatian satire (comic, sympathetic) and Juvenalian (more biting). Sunshine Sketches mocks small people who believe themselves to be large, and Arcadian Adventures reveals the inner smallness of those society considers big.

TODAY, LEACOCK IS LARGELY FORGOTTEN outside of Canada, and much of his work is out of print even here. But in the early twentieth century, Leacock was probably the most famous humourist in the English-speaking world, mentioned in the same breath as Twain and Mencken. His stories about characters in small-town Canada were published in New York and London. Sunshine Sketches, published in 1912, introduced readers to Mariposa—based on Orillia, Ontario, where Leacock spent his summers away from Montreal—and its inhabitants. Mariposa may be small, but for Mariposans, it might as well be Paris or Rome. “Of course if you come to the place fresh from New York, you are deceived,” explains the narrator. “But live in Mariposa for six months or a year and then you will begin to understand it better; the buildings get higher and higher; the Mariposa House grows more and more luxurious.”

The comedy of the individual stories measures the gap between the characters’ pretensions and their accomplishments, gently pulling back their unconvincing facade of sophistication and importance. The owner of the town’s most prosperous bar runs for parliament on a temperance platform. A fundraising campaign for the local Anglican chapel actually costs more money than it raises, and only by burning the church to the ground and collecting the insurance money are the parishioners able to redeem it. The Mariposa Belle steamship sinks in Lake Wissanotti (depth: six feet), and a rescue party is organized; the relief boats are themselves leaky and the heroic rescuers barely make it to the steamship in time to clamber aboard to safety.

Leacock, despite the acidic nature of his deft caricature, loves his Mariposans, and the comic tone of the stories is sometimes interrupted by a strain of avuncular warmth. The tension between irony and sympathy, distance and proximity is finally explained when, in an envoi, Leacock makes it clear who you, the reader, are: an old Mariposan who grew up, left for the big city and prospered. Now and then you recall Mariposa with fondness, but sitting in your comfortable leather chair at the swank Mausoleum Club, you never seem to find the time to go back and visit.

ALTHOUGH SUNSHINE SKETCHES has been enshrined in the Canadian canon as Leacock’s classic, Arcadian Adventures with the Idle Rich, published in 1914, was initially a far greater critical success. Arcadian Adventures is set in “the City,” a nominally American metropolis which could be Boston or Chicago but is almost definitely Leacock’s own Montreal. Basking in the afterglow of turn-of-the-century meliorism, still controlled by an Anglo-Scots Protestant elite, it was the financial centre of the Dominion of Canada, home to the powerful and magnet for the ambitious.

Inside the Mausoleum Club, sitting in leather chairs under plumes of cigar smoke, are some of the City’s most influential citizens, holding forth on “great national questions, such as ... the sad decline of the morality of the working man, the ... lack of Christianity in the labour class, and the awful growth in selfishness among the mass of the people.”

The wheels of greed and narcissism begin to spin. The oily Lucullus Fyshe has made a side-business of squeezing money from naive European aristocrats visiting the New World, so he’s excited to learn that a potential mark, the Duke of Dulham, will soon be in town. Little does he realize that the Duke—representative of a certain genre of pedigreed but perpetually cash-strapped British peers—is in town because he hopes to borrow money, not lend it. Meanwhile, the Presbyterian and Episcopalian churches compete to save the most financially generous souls, and the rectors of Plutoria University hustle potential benefactors through the university gates, cowing them into submission with a constant stream of Latin. The students of Plutoria U, seized with sudden political enthusiasm, hold a “demonstration” where two students are arrested. “Only by an error,” explains the university president. “There was a mistake. It was not known that they were students. The two who were arrested were smashing the windows of [a streetcar] ... with their hockey sticks [and a] squad of police mistook them for rioters.”

As with Sunshine Sketches, the tone is comic, almost cartoonish. But there’s a darker undercurrent that sometimes boils over. The wealthy Newberrys have an estate outside the City, where their love of nature compels them to constantly dynamite the grounds to make room for piazzas and tennis courts. In the course of one construction project, two labourers die. “But of course it is dangerous [work],” explains Mr. Newberry. “I blew up two Italians on the last job ... I had to foot the bill for them all the same.”

By the end of Arcadian Adventures there is no doubt whatsoever about Leacock’s sympathies, or lack thereof. The final story, the ironic “The Great Fight for Clean Government,” ends with the crooked but essentially democratic municipal government replaced by a crooked and essentially autocratic one. The newly-crowned elite gather to celebrate, and fittingly close the book at the same place it opened: the Mausoleum Club. They party 'til dawn, when, finally exhausted, “the people of the city—the best of them—drove home to their well-earned sleep, and the others—in the lower parts of the city—rose to their daily toil.”

“PLUTORIA UNIVERSITY”—that great research institution, gates opening onto Plutoria Avenue, filled with scheming deans, drowsy academics and zealous student activists—is, of course, Leacock’s own McGill. It’s delicious to think that McGill named one of its most prominent buildings after a scholar most effective when ridiculing the pretensions of that same university.

It’s a little more discomfiting to know that an academic hall is named after an aggressive proponent of British imperialism and opponent of women’s suffrage. The same writer who wrote stinging satires of economic inequality left us a corpus which is condescending toward non-whites and women even by the standards of his time. Leacock might be alarmed to learn that, today, students are taught subjects like post-colonial discourse and feminist theory in his namesake building. Or perhaps he would be tickled: it seems like a fitting back-handed salute to a master ironist.

Arcadian Adventures and Sunshine Sketches are an uneasy critique of modernity, their literary tensions mirroring the politics of their author. Leacock was an instinctual pink Tory in an age when conservatism was liberal capitalism’s determined foe, not its greatest booster; his town-and-country parable springs, finally, from the nostalgia of an economic and political reactionary. A condescending warmth for le petit peuple motivated the gentlest of his comedy, but he brought the cold, ironic distance of an aristocrat to bear on the highest strata of his society. Perhaps Leacock knew that he, like many of the best satirists, was implicated in the very subjects he skewered.

Oh—and the Mausoleum Club, the symbol of all that is decadent and corrupt and complacent in the industrial metropolis? It’s Montreal’s University Club, a private members’ hangout which still exists on Mansfield Street. Leacock was well-acquainted with the place: he co-founded it. He could be found there almost every evening—sitting comfortably, near the window, in his favourite leather chair.