Brecken Bad

An interview with Brecken Hancock about her new collection, Broom Broom.

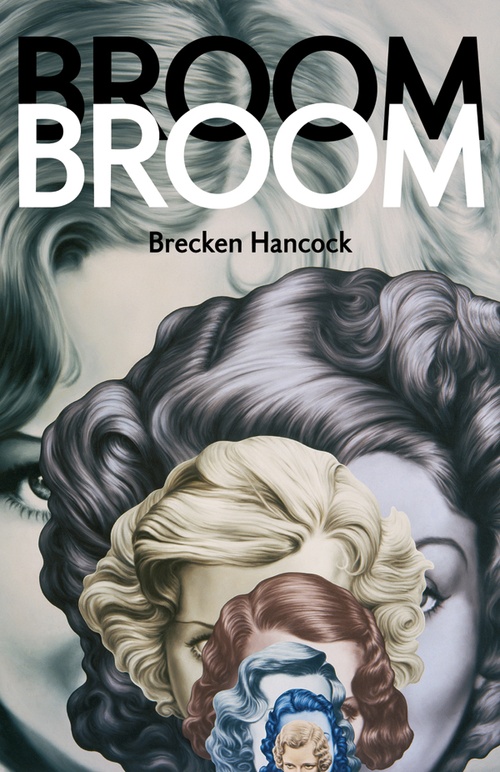

For Brecken Hancock, The Notebook was anything but romantic. The novel, selected for a book club, angered her; the movie didn’t fare much better. She says that too often, a character “slides into a beautiful type of forgetfulness, when actually [dementia] is very physically violent.” This is a subject she broaches in her debut collection of poetry, Broom Broom (Coach House Books, 2014).

Hancock, who lives in Ottawa, is the interviews editor for Canadian Women in the Literary Arts and the reviews editor for Arc Poetry Magazine. Her own work has appeared in Lemon Hound, the Globe and Mail, Hazlitt and Studies in Canadian Literature. She spoke with me about her collection.

Erica Ruth Kelly: What is your usual creative process? Was that the process you used for writing Broom Broom?

Brecken Hancock: I have a nine-to-five job, so I work a lot on the weekends, usually Saturday and Sunday mornings. I use my vacation time for writing. Last year, my husband and I got married on Thanksgiving weekend. As our honeymoon, we rented a cottage in Vermont and just wrote both our books. It was great, because that was what helped me finish Broom Broom. Some writing sessions are incredibly frustrating and lead to very poor product. But I find just that persistence, throwing a lot of sweat at the page, is what works for me. I’m a very heavy editor of my own work, so if I don’t make the time to write that crappy first draft, then I’ll never get to the better thing that I think is around the corner.

ERK: Did you have an outline of how you wanted it to come together, in terms of the structure of the book?

BH: Not at all. That was something that was very mysterious to me, how it developed. This is my first book and it took me about four years to write, but before that, I had written tons and tons of pages that I just ended up throwing out because I was in search of something. I was in search of the voice that would become the voice in this book.

When I first caught it, I knew that something different was happening in my work, but I didn’t know where it was going to lead. It didn’t have a structure and it didn’t have a map. I inhabited that place for a long time. I had all these kinds of pages of things that were loosely related, but I didn’t know how they were going to unfold in terms of the linear structure of the book. I played around with the order.

At some point in the process, I knew that there were a couple of pieces missing and at that point I applied myself a little bit more rigorously to doing something pre-planned. And it ended up working out really well. The end was what I wrote last. I wrote “Evil Brecken” and “Once More” last; I felt those were the missing pieces of information that would help the book to come full circle.

ERK: You just touched on something interesting there, because the penultimate poem, “Once More,” which discusses your mother’s illness in a very straightforward way, really changes the reading of all the poems that came before it. Was that your intention with the sequence of the poems?

BH: I did intend that. With “Evil Brecken,” there’s a potential to hide vulnerability behind the craft, and “Once More” was prose-like and confessional in the boldest possible way. I struggled with it a little bit, because if I hadn’t published “Once More,” the rest of the book wouldn’t necessarily have had to rest so absolutely in the confessional. I think that when I embraced putting “Once More” at the end of the book as the penultimate poem, I was embracing that reading of the book as confessional.

ERK: What inspired your allusions to classical mythology, animal sexuality and gender reversal throughout the book?

BH: Animal sexuality, the gendered nature of the people in the book, the metaphor of incest and classical mythology were all research elements and pieces of data and history that I was kind of obsessed with intellectually. Using classical mythology and animal sexuality to talk about the personal: the interior of the household, personal relationships with the parent, human sexuality, family violence, all these kinds of things, was a careful balance. It’s so easy to become hysterical with the subject matter, so in some ways the classical mythology allowed me to step back and to allow to filter it again through another type of storytelling.

ERK: In the poem “Mount Sappho,” the use of nouns as verbs, for example, the phrase, “as we cannibal,” detaches them from a fixed point. Were you trying to give nouns more of a transformative power by using them as verbs?

BH: Yeah, definitely. And I think in that poem the torque comes from not only the sounds, side by side, but seeing words that we’re familiar with repurposed. I think with a poem like that, which is so abstract, the way the reader can get carried through the poem is through that movement and the surprise at encountering words in new contexts.

ERK: I’m curious about the book’s interest in bathrooms. In “The Art of Plumbing,” the bathroom has such a dichotomy. It’s the room where you get clean, but subsequently becomes the dirtiest room in the house. What drew you to this image?

BH: For me, it’s like a piling up of things. The reason I told that story about the art of plumbing was through this very circuitous, personal story. My mother rescued this clawfoot tub off her in-laws’ lawn. They were remodelling their bathroom and they tore out this bathtub and she asked if she could have it. And by some crazy sequence of fate and intention, [the tub] followed us to five of our houses. There are all these family stories about it. It never made its way into the book, but I’d wanted to tell that story about this heirloomed tub and try to use its history and timeline to try to track my family’s history and timeline, then the history and timeline of my mom’s illness.

From there it just kind of mushroomed into this obsession with baptism and sarcophagi and all of the ways the bathroom has been used for both purposes—the metaphor of immortality in baptism and as the actual housing of the body after death. It’s so fascinating to me. I still get excited if I think about it.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Follow Hancock on Twitter @breckenhancock. Follow Kelly on Twitter @ericaruthkelly.