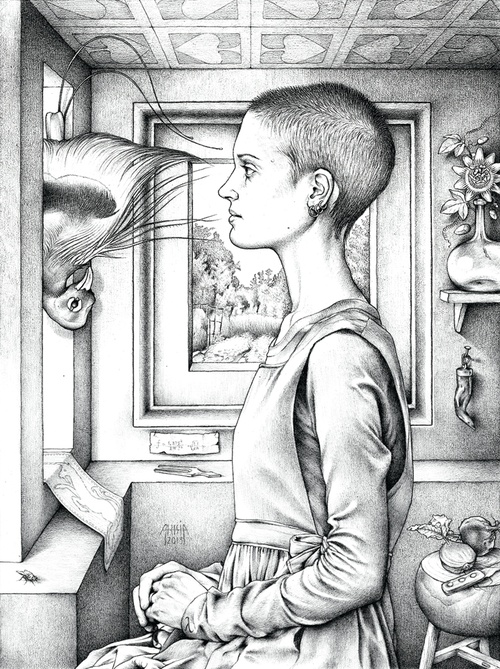

Illustration by Arhia Kohlmoos.

Illustration by Arhia Kohlmoos.

Estocade Cacharel

Originally published in la revue Moebius (No. 137, Mai 2013). Reprinted with permission. Translation by Melissa Bull.

Dad was a bad egg. He wasn’t the type of guy who’d

beat around the bush or tread lightly over anyone’s

feelings. People who were too uptight or who liked

to toot their own horns got on his nerves. If he was

channel surfing and had the misfortune of landing on Radio-Canada’s Denise Bombardier, we’d

all have to hear about it. His neck and chest would

turn bright red and every thirty seconds he’d get

up out of his La-Z-Boy to hurl a slew of insults at

the television, at the walls, at the neighbours, at the

prime minister, at the universe, at all who fell within reach of his voice, most notably my mother and me.

His fits of logorrhea treated us to such comments as: “Listen, smartass, we’ll pay attention to you when you’ve got something worth saying!” Everything he said was fueled by a visceral hatred we’d long ago renounced any hope of understanding. It would take him hours to simmer down. The best birthday present I ever got was a bulky set of noise-cancelling headphones from my godmother the year I turned fifteen.

When my mother was absent, he’d come into my room and yell at me for no reason. When she’d get back from her errands or her bridge night with the girls, she’d find us at each other’s throats. He could bring out the worst in me like no one else.

My mother finally left him after he got trashed and destroyed everything fragile in the house. He spent the last years of his life in the big city, aging, shrinking, getting fat, his spirit more and more soaked in the alcohol he’d drink from morning to night, his judgment flailing, his character ever more expansive.

Before he was hospitalized, I’d take him to the grocery store every week to make sure he’d eat something other than delivery pizza. Gripping the shopping cart like a walker, he wouldn’t pay the slightest heed to the thousands of attention-grabbing labels or foods. He seemed content to stare straight ahead and answer my questions curtly.

“What do you want for breakfast?”

“Corn Flakes.”

“For lunch?”

“Hamburgers.”

“For supper?”

“Spaghetti with tomato sauce.”

“For dessert?”

“Orange Jell-O.”

“And for fruits and vegetables?”

“Radishes.”

“That’s it? Just radishes?”

“Yeah.”

The menu never changed. I’d given up the notion of suggesting any variations to his well-established dining habits. He’d just follow me around, shuffling his feet like a zombie in the supermarket’s overly-bright aisles, affecting an air of profound boredom. Once we were in line to pay, though, he’d snap out of his torpor, excited by the proximity of the other shoppers and of the exit. He’d start cracking his condescending remarks. “Hey, check out that tart in the bikini on the magazine—she’s not shy, eh? I bet she’s the type who likes to get her ass grabbed. She’s built! I’d teach that girl how to respect herself—Ha! Ha!” His greasy laughter always shifted into a shallow, persistent cough.

Once it was our turn to pay, he wouldn’t speak to the cashier. He’d toss his money onto the rolling carpet, making the cashier unglue his coins from the rubber one by one. He’d rip the bill from her hands and go over it scrupulously, suspicious of errors. He’d slit his eyes and say, in his vile tone, “Wasn’t the mustard $2.29? Seems to me the price was $2.29.” I’d have to convince him not to call the manager for a price check. Still, at least, in these moments, it was the weakened, end-of-life translation of my father’s anger.

My father impressed me until I was fourteen. He talked, laughed, fucked and got angry loudly. He was respected by everyone and he knew everything. But my perception of him changed when, by fluke one summer afternoon, I saw him step out of the town’s only strip club. With him was a blonde with an unstable gait. He was supposed to be playing golf. I hadn’t recognized him at first because his face bore the same expression as the men I’d often see staggering outside that bar. I’d imagined them without families, jobless bums. The same night, seeing my mother fidgeting and sucking up to him, I realized my dad was dead to me and that I had to start getting used to living with this shady character whom it was better not to know. My change in attitude towards him was spectacular. But they just blamed my adolescent crisis.

It was around that time I met an emaciated, clear-eyed guy named Jimmy. I’d wait for him after school and we’d go up to his room to listen to Metallica and play Risk. Jimmy’s dad was generally sitting on the sofa in front of the TV and he was content to lift his arm lethargically in salute, never taking his eyes off the screen. He was a big guy, and he’d sit there, shirtless, pants unbuttoned, slumped in his opaque cloud of smoke.

From Jimmy, I learned that on the nights my dad told my mother he was going to his AA meetings, he was actually smoking joints and watching triple-X movies with Jimmy’s dad. The two of them would shout out comments and laugh their heads off like morons. My dad only asked me once if I wanted a lift back home but probably understood the extent of my disgust from the face I made. He never asked again.

I really had it in for him. I hated myself for having worshipped the loser who’d carried me on his shoulders at the grocery store when I was little and would run around shouting, “Watch out! I’ve got a little bomb! It’s gonna blow soon!” I would dress in black from head to toe to mark the end of my childhood, which would provoke him to say, “So what, you’re going to a funeral? Put on a turtleneck while you’re at it. You’re about as sexy as a brick. No wonder you don’t have a boyfriend.” I started to punctuate my sentences with words he didn’t know just to get his goat. He’d say, “Christ, you think you’re smarter than everyone with those hundred-dollar words. That’s not how you make friends. Snobs all die alone.”

My father died in July. His last words to me were: “I just wanted my little girl to be normal. Fucking normal.” Hiding in the hospital bathroom to cry in peace, I caught sight of myself in the mirror: tall, with short bleached hair, an eyebrow ring and tattooed arms. But what devastated my father was that I liked girls.

Mourning was harder than I’d imagined it would be. I dreamed of my father every night for months at a time. At times he was tender. At times grotesque. But it was him, it was always him, resplendent in his arrogant ignorance.

Follow Melissa Bull on Twitter.