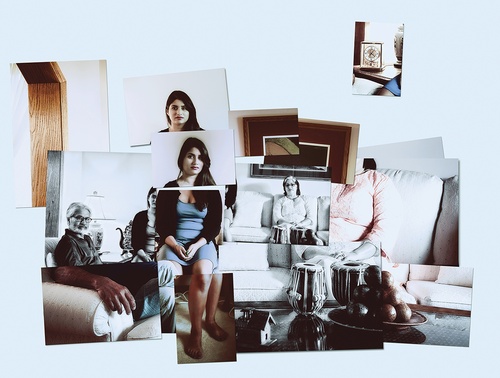

Photograph by Todd Korol.

Photograph by Todd Korol.

Face of the New West

Has Naheed Nenshi's time in office changed Calgary's racial climate?

I WAS IN THE FIRST GRADE when a guide dog defecated in the library of my elementary school. A neat dollop of feces next to a shelf of old VHS videos is gross, even more so when a group of six- and seven-year-olds are the first to find it.

Everyone whispered that Vivek* did it. He was the only other brown kid in my grade. He had trouble with his English and a slight lisp. He ate aromatic lunches, the sort of meals my parents served me for dinner. He didn’t have any friends.

My classmates had reasoned that Vivek did his business in the library “because he’s the same colour as poop.” Later, when I realized I had stepped in the offending pile, I quickly scraped it off on the carpet in a hidden corner near the Goosebumps novels, worried that if the other kids saw it, they’d assume I, too, leaked dog shit just because I was brown. It didn’t matter much: the next week, the kids in my class started a chant about how Vivek and I needed to get married because we were the same colour. This wouldn’t be the last time the shade of my skin made me a target.

At summer camp six years later, I would be asked to eat my lunch elsewhere because I was “too dark” to sit with the popular girls. In the seventh grade, Graham S.* would call me “Osama bin Laden’s cousin” for an entire year, a real mouthful from a kid who stole and ate erasers for a living. In the eighth grade, two boys in my biology class bought me a stick of deodorant to mask my “curry smell.” I was called a nigger four times between tenth and twelfth grade. There was one black kid at my high school. His name was Prince, and people just assumed he was a drug dealer.

Despite being born and raised in Calgary, I always felt that the city was too white for me to fit in. In 2008, Jaspal Randhawa, a Canadian-born accountant, won a discrimination lawsuit against downtown’s Tequila nightclub after he was turned away at the door, told that the owners didn’t want clients to say that “there are a lot of brown people inside.” I still remember watching a CTV News segment when the story first broke: it felt like proof that the discrimination I grew up with wasn’t just children being children. The white anchors reported on the incident with hushed tones and wide eyes as if to say, “Racism? Here?” I asked my parents how a business could get away with doing something like that and they just shrugged it off. To the white news anchors, it may have seemed shocking, but to us, it was so common that it barely merited a response. For people of colour in Calgary then, visibility meant little more than the public acknowledgement that maybe, now and again, things are not so fair for you.

But in 2010, my white former classmates started sharing photos and campaign links for one of the mayoral candidates in the upcoming Calgary election. Naheed Nenshi seemed like a longshot back then. He championed the arts and public transit, spoke directly to the thriving immigrant community—and he was brown. He wasn’t just liberal; he was a Muslim, glasses-wearing intellectual whose parents lived with him. Charming, approachable, innovative, gentle, funny and connected, he used social media to get his message out and to bring young professionals on board. In October 2010, he was elected in the highest voter turn-out in Calgary’s history: 53 percent, up from 32.9 percent the election prior. Nenshi didn’t just make people vote for him, he made people vote, period.

By then, I was living in Toronto. Friends from every other part of Canada asked me how it was possible that a brown man had won an election in the “whitest” city in the country, when, a few weeks later, Rob Ford was settling into office in my new, left-wing, “multicultural” home. I was struggling to make sense of it, too. How did this happen in the same city where I got pelted in the face with snowballs for being the wrong colour?

Nenshi’s mayoralty feels like a turning point in Calgary’s history, but it’s hard to nail down what—if anything— has actually changed for the city’s racial narrative. Returning to the city after he was elected was like coming home to find that my parents had rearranged the furniture while I was away at school. I knew something was different but I couldn’t say what it was.

CALGARY’S sprawling metropolitan area is split into quadrants: northwest, southwest, northeast, southeast. The south is largely made up of conservative white people, while the northeast is home to a large percentage of the roughly 81,000 South Asians who live in the city. Property is cheap, and new immigrants have built a hub replete with Indian jewelers, Punjabi markets and sweet-meat shops boasting glass cases of electric-orange ladoos and pistachio-green barfis. You can move to the northeast of Calgary from India or Pakistan and never need to speak a word of English. (The only exception is if you own a fabric shop and need to communicate with the Hutterite women who drive in from the country to buy rolls of floral patterns for their floor-length dresses.)

Congregating in these blocks did more than create a cultural centre; it gave immigrants an unprecedented kind of political influence. Politicians now had to focus attention on these communities since they served as “vote banks.” The more immigrants came together, the more agency they had in their new country.

My parents and brother emigrated from India more than a decade before I was born, part of the “good” immigrant narrative: they came from another country for a more prosperous life here and became productive Canadian citizens. My dad moved first, into subsidized housing in the southeast, and worked at a shoe store despite his university education. My mother and brother came a year later, and the family moved to their first home in North America, no longer subsidized. By the time I was born in the early nineties, my dad had found a job as a pharmaceutical representative for a prominent drug company. He played a lot of golf and knew a lot of doctors and made a lot of money—the Albertan dream. He was established enough to afford the more expensive real estate in the southwest. My mother was a housewife who tended to a sprawling four-bedroom home with toilets that weren’t holes in the ground. Our family rarely ventured to “Little India.” The only close link we had there, beyond a few friends, was Farrah Auntie, who measured and cut all my outfits for Indian dance class.

We lived in a neighbourhood of big things: big SUVs, big trampolines in big backyards, big dinner parties. My dad bought a Mercedes-Benz for my mother and then dared to complain about the mileage. My mom upgraded her wedding ring to a diamond bigger than the hand that dug it out from the ground. My extended family worked hard to make sure their children were integrated. We spoke seamless English, celebrated Christmas, played organized sports. They didn’t bother teaching us Hindi or Kashmiri. My friends were white because that’s who our neighbours were. By thirty-five, my brother had passed the bar, gotten married, had a daughter and moved into his second home. For Christmas, my parents bought my then-three-year-old niece an indoor tricycle and a stack of Disney Blu-Rays to watch on their wide-screen television.

A decade ago, when my mother and I would go to the mall close to home in southwest Calgary, we would often be the only faces of colour. When we went Boxing Day shopping last year, she pointed out how many Chinese people were in the store—more and more, we see non-white families in our traditionally white neighbourhood.

It’s a valuable change, even if it feels a little gauche to point out, and a statistically tangible one. In the 2006 census, more than 56,000 Calgary residents reported being of South Asian origin. In 2011, it was just over 81,000. The total visible-minority population in the city went up by nearly 93,000 people. In 2011, there were more than 20,000 people reporting that they could speak Hindi, more than 34,000 reporting Punjabi and more than 25,000 reporting Cantonese. In 2010, the total immigrant population was estimated at just over 300,000 people. It’s projected to reach nearly half a million people by 2020.

MAYOR NENSHI MEETS ME at the Max Bell arena in southeast Calgary. He’s dropping the puck at the AAA Midget Hockey tournament. I do a quick scan of the six hundred people in the stands, and there are just three brown guys and one Asian girl. (I feel this kind of kinship with her—she’s hanging out with her white friend’s family, looking around, seeming bored. Me too, sister.) This scan is a reflex of sorts, something I started doing in junior high, a silent tally of exactly how other I was in any given place. But hey, it’s hockey. Hockey is pretty white wherever you go.

We can hardly get Nenshi to the ice. People are stopping to shake his hand and tell him how great he is. After a long wait and a quick speech, we leave the arena to find a quiet place to chat. Before we get away, however, we hear a squeal in a frequency usually reserved for training police dogs. Behind us, a pack of teenage girls comes running, wearing Calgary’s unofficial uniform: ski jacket, meticulously straightened hair, Ugg boots. They’re screaming Nenshi’s name, begging for a picture, hopping lightly on their toes with excitement. Nenshi readily obliges, smiling in the middle of a line of white sixteen-year-olds. What is he, a Kennedy?

We leave the arena to go to an office in the back, interrupted two more times in the five minutes it takes us to walk there. “You know that’s not normal, right?” I ask him after we sit down. He fiddles with a black binder clip he’s found on the table, his eyes closed for a brief moment, a bashful smile on his face. “That was actually pretty muted.” He somehow manages to both bask in the attention and be embarrassed by the sheer extravagance of it.

Nenshi is like the anti-Rob Ford. Well into his second term, he’s still one of the country’s most popular politicians. Toronto-born and raised in Calgary, he is the son of two immigrants from Tanzania of South Asian-origin. Like so many of the first-generation Calgarians who voted for him, Nenshi is both a visible minority and a born-and-bred Canadian. He looks younger than his forty-two years, with an easy, contagious buoyancy. He is by no means a slender man. (Doug and Rob Ford tried to get Nenshi to join them in a weight loss challenge in early 2012, to which Nenshi replied on CBC, “Did they call me a fatty?”) His meaty hands and broad shoulders would make him an intimidating figure if he ever stopped smiling.

In his first mayoral race, Nenshi was the underdog. While then-councillor Ric McIver and former CTV journalist Barb Higgins duked it out as the two leading candidates, Nenshi picked up most of his votes in the final weeks of the campaign. He jokes he was the “dark horse” candidate, before dryly adding, “ha, ha.” Now, he mans his own Twitter account with 212,000 followers and goes to countless public events every year. He has invested hundreds of millions of dollars into improving Calgary’s transit system and bolstered the city’s arts programs (he even asked local kids to send in their art depicting 2013’s flood).

The mayor doesn’t think his ethnicity was a factor in his first election. “Other than the neighbourhood in which I live, the other South Asian neighbourhoods were really tepid in their support the first time around.” He claims his race didn’t really become a focal point until after his 2010 municipal win, when the rest of the country noticed. “Suddenly national and international media were like, 'What happened there? That guy doesn’t look like Calgary.’” It probably helped that the guy who did look like Calgary—ruddy-faced, dismissive, conservative Rob Ford, with his record of racial slurs—was elected in another very big Canadian city.

AFTER NENSHI’S WIN, I thought about Vivek, and how horrible I was to him because we looked the same. Vivek didn’t come back to school the following year and I never saw him again, but man, if he still lives in Calgary, wouldn’t this be the best revenge in the world? It was thrilling to think my hometown could have moved beyond the racial bias I always sensed there, mostly for the sake of my niece. She was just a few months old at the time, a half-Indian child, the only other family member born in Canada. I wanted her to grow up in a kinder Calgary than the one I remembered. I wondered whether Nenshi’s mayoralty would make things easier for my niece as she tries to navigate what is now Canada’s third most diverse city.

When I suggest Calgary might have more of a race problem than, say, Vancouver or Toronto, Nenshi demurs: “There was never a moment growing up where I thought there was any job I couldn’t do because of my race or religious background.” I’m inclined to consider this a politically correct sound bite until he finishes: “I just went ahead and did it.” At the time he was elected, “we were a province that had a Muslim mayor of its largest city, a Jewish mayor of its second-largest city, a female premier and a female leader of the opposition. When was the last time Toronto had a nonwhite mayor?” By contrast, Nenshi points out that Alberta’s South Asian community has long had a strong presence in provincial politics.

Dr. Raj Pannu, former leader of the Alberta New Democratic Party as well as the first South Asian leader of a major political party in Canada, was first elected in 1997. His constituency in Edmonton wasn’t exactly overflowing with visible minorities, and race wasn’t a talking point in his campaign. Instead, he was careful to play up his degree: adding “Dr.” to the start of his name on his campaign literature. “It’s hard to be peddling your degree, but that was the decision that was made deliberately to override any concerns that people might have at the door with respect to my cultural or racial background,” he says. At the same time, his race connected him with a voter base in Punjabi and Indian communities. “They all told me they found my presence on the political scene very inspiring, very enriching, very encouraging.”

Nenshi is not a mayor elected by brown people for brown people, but his presence at City Hall does resonate with people who look like him. Kaleem Khan, an old classmate of mine, was one of the many voters promoting Nenshi on Facebook during his first election. “If you’re a minority, and you can identify with someone who is in power, it makes the burden of being a minority a little lesser,” says Khan, who is now a musician. But, he adds that having Nenshi in office has far from solved everything for the city’s South Asian population.

This year, the Calgary Stampede ran during Ramadan. Nenshi attended a break-the-fast breakfast at sunset for the Ismaili Muslim Community. There was Mayor Nenshi, wearing a white cowboy hat at dusk. But Khan says that Stampede is still one of the most difficult times to be a person of colour in Calgary. “When people are drunk, I think what happens is a lot of things that they’re trying to conceal are brought to the surface,” he says. The moments he mentions sound like the Alberta racism I remember: drunk yobbos hurling racial slurs, men wearing turbans on the C-train being harassed when they’re just trying to go home.

MUCH LIKE OUR MAYOR, my dad doesn’t think the colour of Nenshi’s skin holds much significance for the city. “By the time he came, this city had evolved to such extent that people who are at the helm of affairs were assisted by people from all over the world,” he says.

My mom is nearby in the living room of the home where I grew up, playing Shoots and Ladders with my niece. “I wanted a brown mayor,” she says quietly, adding that she voted for him the first time around solely because of his ethnicity. “Racism is still here. It hasn’t gone with Nenshi coming or going.”

Dr. Pannu calls the current racial climate in Calgary “a certain kind of racism.” It isn’t as aggressive as it was when my mom was being called a paki by a woman in her neighbourhood (she had never heard the word, and had to ask my aunt what it meant), but it persists. “Racism is an insidious phenomenon,” Dr. Pannu says. “It doesn’t disappear overnight.”

A 2013 video of a charming Calgary woman telling a neighbour, “Maybe you should go back to China where you belong,” went viral. Later that year, Vice published a piece about a surge in neo-Nazi activity in Calgary, where white supremacists were throwing bricks through the windows of anti-racism activists’ homes. These are the things we can quantify, the instances that are easy to point out. It’s harder to make sense of, say, how people look at you at the shopping mall.

My mother now works as a middle school lunchroom supervisor and still sees race-related bullying. “There are two East Indian kids sitting in grade seven or eight. The same grade kids will shove them off and say, ’Leave this table.’ But if two white boys are sitting there, they won’t tell them anything,” she says. “A lot of times, these brown kids’ parents call and say ’Why isn’t my kid finishing his lunch?’”

My dad picks up a Kentucky Fried Chicken flyer and begins to read it like it’s Ulysses. “You can’t form an opinion on a city or community based on what children are doing,” he says. But why not? Aren’t they the purest reflection of how adults behave, what adults do, what they say? Aren’t they the most likely to tell us what they’re actually feeling?

After my interview with Nenshi, I met with my old high school English teacher, Wayne Valleau, at Starbucks in the southwest. At seventy-three, he’s been living in Calgary for four decades. “Calgary has gotten bigger,” he says, referencing the city’s massive sprawl. “It hasn’t gotten smarter.” As a white guy living in the city, he hasn’t noticed much of a change since Nenshi was elected. “I mean—” he stops short and gestures towards everyone in the coffee shop. It takes me a second until I catch on: I am, as usual in this city, the only person of colour amongst the forty people here. He watches my face and lets out a big laugh. “See?”

Before we leave, I tell him about Nenshi’s claim that racism doesn’t play as big a part in Calgary as I think it does. He shrugs his shoulders. “Othello would never admit that Venice is racist.”

“THERE IS A GENERATIONAL change that’s happening,” Dr. Pannu tells me. “[For immigrants], the priority is to settle down, find work to do, raise kids, make sure that they go to university and college. The first generation is very much focused on personal goals. The public sphere opens up to the second and third generations, people of your background,” he says. “Your aspirations reflect Canadian reality more than ours. Nenshi is a part of that second generation.”

By necessity, the children of first-generation immigrants live in a multicultural world that is neither one thing nor another. There is a specific kind of baggage in this, juggling a culture you are born into that you never really touch, and one you should naturally belong to, where you look so different from other people. The hope, then, is to blend the society you do grow up in with the one you would have if your parents had never left the old country in the first place. (Or at least, that’s what “they” tell us when they talk about the glory that is Canada’s multiculturalism.)

While I’m talking to my parents about Nenshi and race, my niece interrupts, grabs my face, shakes it and then tells me it is time to play Shoots and Ladders. The third generation of my family isn’t just being raised in a different version of Calgary than the one I know, but a different world entirely. My niece, whose white mother was born in Newfoundland, is the first mixed-race child in a family built on the back of a pair of educated immigrants. While I struggled to fit in with white or brown people, my niece can blend in both ways. When we go to the mall near her house, she sees people who look like both her mother and her father. If you ask her, she’ll tell you that she’s “Indian and Newfie-an.” She confuses the English and Hindi word for “naked,” and fuses “tortilla” and “roti” into “rotilia.” If she could pick, she would eat oil- and cumin-laden Indian rice-flour crepes every morning.

For the children of immigrants, it’s not just about having the house and the car and the kid, but about having the society to match. There will be a separate set of goals for my niece. I’m thankful that she goes to school with kids whose names are as international as her own Sanskrit moniker, and while she looks white, she knows she isn’t, and knows plenty of other kids who aren’t either. But more than that, I’m hopeful that she will grow up in a place that is different, better and warmer than the one I know.

My mother asks her to put her game away for dinner. In the living room of my parents’ home is this little girl with blue eyes but thick eyebrows watching Frozen for the fortieth time and eating rice with curried chicken. She never notices that she’s flanked by a couple who moved their entire life across an ocean into a foreign culture more than three decades ago, just so that this, all of this, would go so much more smoothly for her than it did for them.

NEAR THE END OF OUR INTERVIEW, I ask Nenshi if I got something wrong about Calgary in the time that I lived there. “I think you may have,” he says. “If you’re a minority anywhere in the world, sometimes you deal with racists. Sometimes, there’s idiot-people out there. Fundamentally, it doesn’t make a huge difference in terms of your actual potential, and your ability to do great things.”

I walk Nenshi out towards the parking lot—he is noticeably weary and I catch him closing his eyes a few times, as if to try to get a moment’s rest—but before he leaves, he reminds me that no matter where you go, Calgarians can’t escape Calgary. “Eventually you’ll get back there. Just don’t get married to a Toronto guy, that’s all. Or if you do, drag him back, just make sure he’s talented,” he says, opening the door for me. “Everyone comes back.”

My dad drives up right as we shake hands goodbye. He sticks his head out the window, gives the mayor a big wave and hollers, “Good work!”

“Papa,” I say as I sit down, surprised by this sudden sychophantic streak. “You didn’t even vote for him.”

My dad smiles at Nenshi’s car as it speeds off ahead of us. “Ah, well,” he says, turning the heat up to stave off yet another -30 degree Calgary winter. “He seems like a nice guy, doesn’t he?”

*Name has been changed to protect anonymity.