Black Mirror

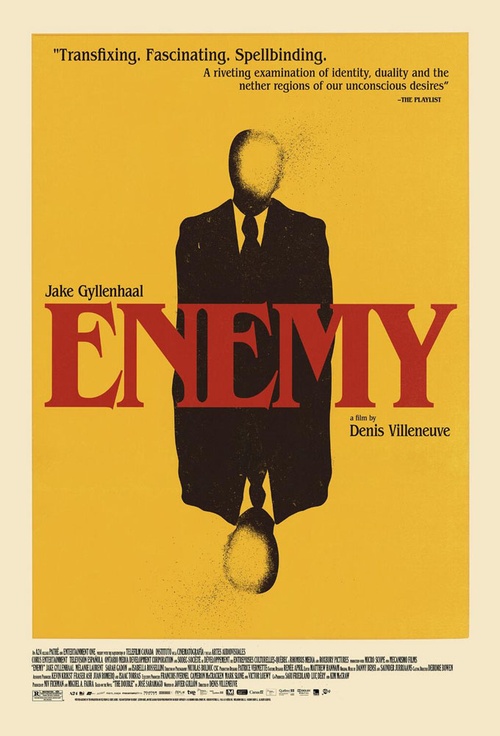

Denis Villeneuve’s Enemy, starring Jake Gyllenhaal, explores the radical instability of post-modernist urban life.

In Denis Villeneuve’s Enemy, history professor Adam Bell (Jake Gyllenhaal) references Marx and Hegel as he paces, distracted, across the front of a large auditorium full of indifferent students. “History always happens twice,” he tells them. “The first time it’s a tragedy. The second time, a farce.” Visible on the chalkboard behind him, the word “truth” has been crossed out and the word “reality” is written in quotation marks.

One night, while dreaming of a movie he had watched earlier, Adam stumbles upon his double (an actor named Anthony Saint Claire, also played by Gyllenhaal). Anthony appears very briefly in a short scene as a bellhop and Adam’s subconscious is his tip-off. He awakes, disturbed, then finds the scene on the DVD. Watching and re-watching, he rewinds and pauses to get a good look at the screen, unable to comprehend how he could possibly be in the film. Eventually, he decides to search the city for Anthony.

Enemy is an adaptation of José Saramago’s 2002 novel The Double, but set in a bleak, smoggy Toronto, and like Villeneuve’s last two features (Incendies and Prisoners), Enemy has a horrific ending. Yet the gotcha moment is as confusing as it is forthright. Somehow, the film remains consistently intriguing—and very funny—behind its jumble of psychoanalytic ideas. Enemy explores who, between these physically identical men, is the tragedy and who is the farce.

It’s a little sad watching Adam sit by himself in his desolate and poorly-furnished apartment. His shabby, professorial clothes and strained relationship with his girlfriend indicate an unhappy life. Anthony, on the other hand, is not simply confident, but predatory in his masculinity. He’s got better hair, clothes and a spruced-up condo. He’s married to the pregnant Helen (Sarah Gadon), yet he’s also involved in a creepy sex club.

Needless to say, when Adam finds Anthony, the two don’t hit it off. But the opportunistic, perverse Anthony brainstorms what he considers a brilliant idea. He forcibly switches identities with Adam in order to sleep with his girlfriend, Mary (Mélanie Laurent).

The only person who seems as freaked out as Adam about his doppelganger is Helen. She intercepts Adam’s first call to their residence, mistakes him for her husband, becomes irate when she believes Anthony is pranking her and then slowly realizes something is amiss with the professor’s awkward demeanor. When she hangs up the phone, the frustrated, ineffectual Adam mutters, “shit.” Here, and in many other instances, Enemy balances on a delicate line between absurd, awkward humour and a tension that can’t be described as comedic so much as unsettling. Curios (glimpses of spiders of varying sizes, visual markers of an empty urban landscape and eerie, repetitive clarinet murmurs) remind viewers they’re watching a thriller, even if sometimes it doesn’t quite feel that way.

Helen does her own investigation into Adam and visits the University of Toronto campus to look for him without telling her husband. Not knowing who Helen is, Adam finds her staring at him while the two sit on adjacent benches. He makes some banal small talk before excusing himself. Her wide, probing and slightly fearful eyes indicate her mind in motion: Helen doesn’t know how to handle finding her husband’s double any more than Adam does upon his discovery of Anthony. Has she found an alternative to her husband? The same man she loves, without the brutish tendencies?

Enemy prolongs the uncanny sensations felt by both of these characters, maximizing their dread and their inability to fully acknowledge what’s happening. These moments lull the pace of the film to a crawl, but if they make the viewing experience a little arduous, it’s a welcome challenge. We’ve become so conditioned to characters seamlessly acclimatizing to supernatural conditions that when directors allow their subjects to fully live out the denial and catatonia that would actually result from a surreal situation, it’s we, the viewers, who are wrong to wish the film would just get on with things.

The city is a prominent character in Enemy, integral to its central themes. Villeneuve’s Toronto has no vibrance. The throngs of people one would expect to see in a large city are nonexistent. No cultural places, no industrial spaces. It’s a city full of empty, soulless condos, monuments of our era that might prove embarrassing someday down the line. (If this sounds familiar, you’re probably aware of Toronto developers’ insatiable hunger to build more and more condos.) Since so many of the film’s compositions return to the city’s glass-and-concrete architecture and the people inside their open-yet-suffocating dwellings, it’s hard to miss how isolated the characters are.

Adam lives in an apartment complex reminiscent of the Starliner Towers from David Cronenberg’s Shivers (They Came From Within). One

imagines the building was considered

state-of-the-art in 1975; in 2013 it’s

a shabby, run-down place not worth

bragging about. But is Anthony’s condo any better? Perhaps the only difference is age. It’s not difficult to imagine

the condo decaying into a sterile glass

tower full of sad sacks like Adam who

have let the empty walls around them

define their identities.

Perhaps it is no coincidence, then, that the only conversations that take place, outside of those between the main characters, are between Adam and building concierges—first, at the talent agency where the security guard recognizes Adam as Anthony. This scenario repeats itself at Anthony’s condo when Adam’s fib about “losing his keys” is not deemed at all strange by the young, enthusiastic concierge, who tries to discreetly ask Adam about obtaining a different kind of key, one that would provide access to the next sex show. Adam, of course, has no idea what he’s talking about but says he’ll see what he can do. In his new home, in Anthony’s jacket pocket, Adam finds this key. It’s a mystery what door it could possibly unlock, but such uncertainty is at the crux of both the film and the post-modern society it critiques.