Photographs by Sylvain Dumais.

Photographs by Sylvain Dumais.

Finding a Place

An autistic New Brunswick woman has spent years searching for somewhere to call home. While Savannah Shannon is unique, her story is not.

SAVANNAH SHANNON HAS GOOD DAYS AND BAD DAYS.

On good days, she can crack a great joke, go on and on about Harry Potter and quote Shrek with such deadpan delivery that she’ll have the whole room in stitches. Her bad days can be terrifying. May 31, 2012, wasn’t a good day.

On that day, Shannon’s name was on the schedule at the New Brunswick provincial court in Saint John next to three letters: NCR. Not criminally responsible.

Shannon sat in the prisoner’s dock; her heavyset body hunched and her short blonde hair sticking up on one side, as if she’d slept on it. With her eyebrows knit together in a scowl, she looked older than her twenty-one years. Early that morning, someone had driven her to court from the Restigouche Hospital Centre, a psychiatric centre five hours away in Campbellton. She’d been waiting at the courthouse all morning and she didn’t know where she would sleep that night.

A prosecutor, court-appointed defence lawyer and representative from the Department of Social Development were supposed to meet in front of a judge to decide on a place where Shannon could live without posing a risk to others. Since she turned nineteen, Shannon has been charged with a long list of offences. She’s pushed, she’s bitten; she’s struck someone who was trying to wash her hair. Every time, it’s been determined that she was NCR. Her autism, intellectual disability and mental health issues were to blame for the violence. By late 2010, Shannon had been kicked out of nearly every community home she’d lived in. She was sent to Restigouche and, at the time of this court date, had been there for a year and a half.

Restigouche is intended as a place to treat people with complex mental disorders, aid their recovery and discharge them. It’s not designed to be a permanent home. But for people like Shannon, who have high needs and no options, Restigouche has become a holding tank. In 2012, Jacques Duclos was the executive director of Restigouche. At the time, he estimated that 15 percent of the hospital’s inpatient population could be discharged safely if they had somewhere to go. Today, he’s the chief operating officer, Restigouche zone, and vice president of public health for Vitalité Health Network, which operates Restigouche. He says that now, the percentage might be even higher. But the province doesn’t supply enough supportive places to live, or enough caregivers, to get all those patients into comfortable homes.

Because of a bureaucratic mix-up, no one from the Department of Social Development showed up to Shannon’s court date in May 2012. Shannon’s court-appointed lawyer and the judge discussed the idea of issuing an absolute discharge, which would mean Shannon could leave the court house, free to fend for herself. Her intellectual abilities range from those of a four-year-old to a twelve-year-old. Judge Andrew LeMesurier dismissed the idea, saying he was afraid of relinquishing what little power he had to aid her situation. “If you’re allowed to put me on the street,” Shannon asked, “can’t you at least send me to the Miramichi?”

The question said something about Shannon’s life in recent years—she’d rather be in jail than spend any more time in the hospital. The New Brunswick Youth Centre in Miramichi is a detention centre for youth and adults. It’s where the court sometimes sends people for assessments after they’ve been charged but considered possibly not fit to stand trial because of a mental disorder. It’s also where Ashley Smith, the teenager who killed herself in an Ontario prison in 2007, served most of her time.

Seeing Shannon’s frustration, LeMesurier became equally upset. “Someone has to be responsible for finding a place for her,” he said. “I want that person here.” But no one showed up. “It’s frustrating,” said the judge, throwing up his hands. That night, Shannon made the long trip back to Restigouche.

I was working at the Saint John Telegraph-Journal at the time, and LeMesurier’s quote became my headline (“Judge says waiting for department ‘frustrating’”). By the end of the week, the government was taking heat about Shannon’s case in the provincial legislature. Over the next few days, the local media carried a small flurry of stories about the case. Five days later, court met again, this time with Social Development present and ready with a space in a community residence for adults with complex needs. (The court can send people to the hospital for assessment or to jail, but it doesn’t generally order someone to a specific community home— it leaves that to Social Development.)

Shannon moved to a privately owned residence in Saint John and the department paid for her stay. Those close to her believe that staff at the residence asked Social Development for more funding for an extra caregiver to supervise her. It didn’t happen. At the end of August 2012, Shannon was charged with assault. She went back to Restigouche.

Shannon’s big problem is finding a place to live. There are deep ideological divisions in this country about how to solve that problem. A generation ago, institutionalization was the default for Canadians like Shannon. People with mental illness or intellectual disability, or, as in Shannon’s case, a mix of both, were routinely warehoused in large residential institutions and mental hospitals, some- times for life. It was dehumanizing, expensive and often an affront to basic human rights. Today, the country has shifted to a model based on care in the community. In theory, this takes each individual’s needs, desires and strengths into account. In practice, complex cases like Shannon’s reveal the system’s weaknesses. Upon examination, a key feature of New Brunswick’s adult care system emerges: it’s fundamentally reactive, not proactive, and as a result, people are suffering.

NEARLY EVERYTHING I KNOW about Shannon’s life outside the courtroom comes from Joy Sullivan, the only person Shannon has ever called mom. Joy and her husband Paul cared for Shannon from 1996, when Shannon was almost five, until 2005, when Shannon’s violent behaviour spiraled out of control and she left her foster parents to live in the first of many care homes.

In March 2013, I travelled an hour west of Saint John on the tree-lined highway that follows the snaking shoreline of the Bay of Fundy, past shuttered hotels and piles of colourful lobster traps half-buried in snow, to the hibernating tourist town of St. Andrews, population just below 1,900, where Joy and Paul Sullivan live with their adopted daughters.

Joy Sullivan and I sit on a comfortable couch in her living room, surrounded by many, many family photos. Three of her four daughters—all young adults, all former foster kids—are hanging out downstairs. They had all lived with the Sullivans full-time for a decade or more.

Open on the coffee table is a folder stuffed with papers and sticky notes: Shannon’s file. This is where Sullivan keeps copies of most of the letters she’s sent about Shannon’s case over the years. She’s always been a bit of a squeaky wheel. “I called everybody other than the Queen,” she says, speaking in the slight warble of a lifelong Maritimer.

When Shannon was hospitalized in late 2010, Sullivan gave the provincial government a lot of grief. She says staff at Social Development told her to “back off” while they worked things out with Shannon’s last placement and helped her transition from the hospital back home again. In 2012, Sullivan found out from a friend, who had read one of the stories about Shannon’s case that ran in the Saint John Telegraph-Journal, that Shannon was still in Restigouche. Not long after that story ran, Sullivan left a tearful message on the newspaper’s voicemail service. “I want to talk to you, I guess, about Savannah Shannon,” she said, sounding timid and unsure. “I raised this child.” I called Sullivan back.

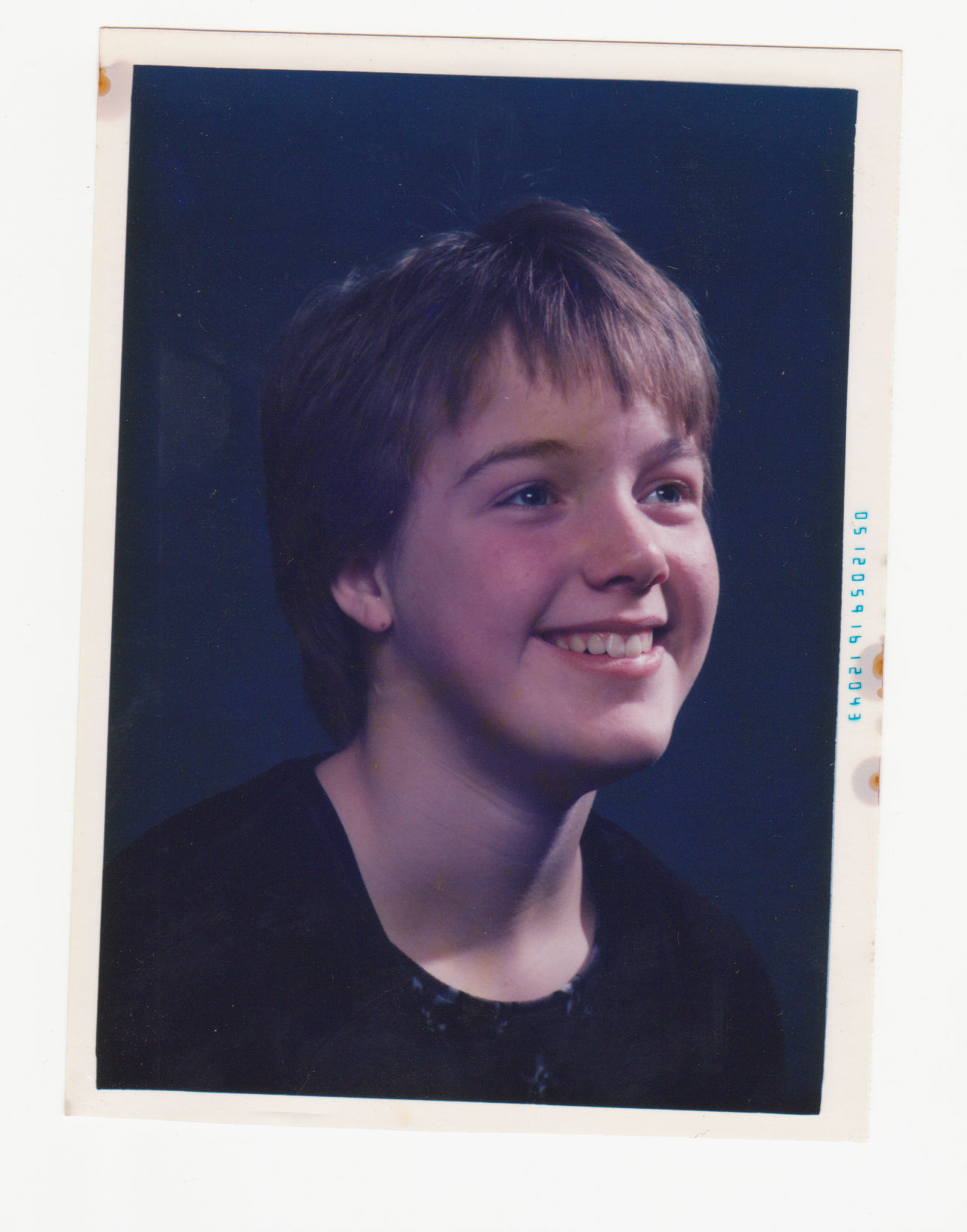

Savannah Shannon’s life wasn’t always so hard. During my visit to the Sullivan’s home, Joy walks into a small room crowded with books, papers and family mementos. “This is my favourite photo,” she says, standing on her tiptoes to retrieve a framed snapshot. “This is the old Savannah.” She’s about nine in the posed portrait. A light shines on her smiling, upturned face. Her apple cheeks are dusted with freckles. “This one, on the other hand,” Sullivan says, pointing to a second picture, “we went from a child who was happy-go-lucky ... to this.”

It’s outside, summertime. A pre-teen Shannon and her foster sisters are standing in front of the house. While the other kids are hamming for the camera, Shannon’s face is downcast, her features obscured by shadows. She looks like a protester guarding an old-growth tree: feet in a wide, defensive stance, eyebrows furrowed, arms splayed behind her.

Shannon’s first few years with the Sullivan family were almost as difficult as her last. The pre-schooler they took in as a foster child had a mentally ill mother who couldn’t care for her and provide the consistent, loving support and early intervention that autistic children need. Shannon’s vocabulary consisted of little more than grunting, crying and screaming. For hours on end, she “flapped;” Sullivan sticks her arms out stiffly and trembles her whole body to demonstrate.

Shannon’s repetitive behaviours were a hallmark of autism, a developmental condition that significantly impairs communication and social interaction. Because of her disability, Shannon struggles with some tasks more than others. The Sullivans used to delight in Shannon’s uncanny ability to solve mazes and visual puzzles faster than anyone in the family. But to test her social intelligence, Sullivan once asked Shannon what she noticed most about the expressions on peoples’ faces. “Noses,” Shannon said.

Still, after about a month of living with the Sullivans, Shannon was talking. She learned to write her name and read simple picture books, but her behaviour in school was always disruptive. Her bouts of tears and laughter could last for hours. She sometimes talked about things that made no sense, even saying she was from another planet. Sullivan says that Shannon might have been the first child with autism her small school had ever seen—New Brunswick passed its inclusive education bill in 1986.

When Paul arrives home from his managerial job at a local nursing home, the Sullivans start reliving memories of “the old Savannah,” whose sense of comedic timing was impeccable. She once stared down a teacher, and, riffing on a line from Shrek, said, “You cut me. You cut me deep.” On one of the many occasions she was sent to see the school principal, she grabbed the back of his head with both hands and gave him a loud, wet smooch on the mouth. “She looked right at him and said ‘Whaddya think about THAT?’” Sullivan says, doubling over with laughter and wiping tears from her eyes. Shannon had a mischievous sense of humour. But her sense of mischief sometimes made others uncomfortable and portended more serious anti-social behaviour to come.

One day, a sobbing special education teacher called the family at home. “She said, ‘I can’t do this anymore,’” Joy Sullivan recalls. Shannon was playing in the school yard with a huge, gleeful smile on her face, crouching by a puddle and pretending to drown a doll.

Shannon’s turn towards outright violence “just kept creeping on very gradually,” Sullivan says. “One day the kids were playing in the pool, and she got really agitated. I had no clue why.” With hardly any warning, Shannon, who was around twelve or thirteen at the time, picked up a shovel and chased her foster mother around the yard with it. In the coming months, Shannon tackled Paul at the mall, yelled “Get this man off of me!” and got him arrested. She pushed a teacher down the school stairs. Someone caught the woman, but that ended Shannon’s formal education. Day and night, Joy and Paul lived in fear. They started sleeping in the basement because the creaky stairs would warn them if Shannon, who had grown heavy, was on her way down. They were afraid Shannon would harm one of the other children.

“I can’t even describe it to you,” Sullivan says. “When I heard her door knob turn in the morning, my stomach rolled over, and I was nauseous. That’s how bad it got ... She sent me flying across the room more than once.” Sullivan was convinced that Shannon’s behaviour signaled the onset of some sort of serious mental illness. Shannon saw every specialist in the book. They tried medications; nothing helped. She didn’t receive a diagnosis other than autism in the time she lived with the Sullivans.

Shannon seemed to lose touch with reality during her episodes. Her blue eyes went dark and, in Sullivan’s words, “all hell broke loose inside her head.” With four other children in the home, the situation was unsafe. Three of the other girls were not yet adopted, and Sullivan was afraid there could be legal consequences if one of them was harmed while in her care. So she made one of the most difficult calls of her life: Sullivan phoned Family and Community Services and asked for someone to come get Shannon.

Shannon moved out in July 2005, at the age of fourteen. For months, she lurched from crisis to crisis, bouncing between several temporary homes. After about a year the department found Shannon a space in a specialized home for children with complex mental health needs. Joy and Paul were thrilled, and they visited often. They say Shannon flourished because she had her own space with dedicated workers supervising her. She had a chance to learn, was able to make some of her own choices and was well cared for. She stayed for four years, but at nineteen she was officially no longer a child. She had to leave.

A CENTURY-AND-A-HALF AGO, New Brunswick’s Provincial Lunatic Asylum was built on a high bluff in the small bucolic village of Fairville, its location no doubt informed by Victorian beliefs about the ills of urban life and the robust health to be gleaned from fresh air. The complex, which was later swallowed by the growing city of Saint John and renamed CentraCare, seemed to reproduce of its own accord, with new wings and buildings growing out from old ones. According to local historian David Goss, student nurses lived in abject fear of their mandatory practicum at “the Provincial.” In the hospital’s early days, some patients were shackled by their wrists to the walls, and isolation rooms had sliding grates for doors. Ghost stories about the troubled souls who perished on the grounds persist to this day.

By the 1950s, it had expanded into a village with a population of about 1,700 patients. But around the same time, new anti-psychotic drugs became available. This meant that for many, mental illness was no longer a life sentence. Over the next two decades, most experts and academics came to see institutions as ineffective, inhumane and expensive, says David Wright, a professor of medical history at McGill University in Montreal. Residential institutions in Canada downsized and closed at a fairly steady rate between the 1950s and the 1990s. In the 1970s, CentraCare began to shed patients.

The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, signed in 1982, prevents discrimination on the basis of disability, while the 2006 United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which Canada signed in 2010, gives everyone the right to participate in economic, social and cultural life, and to choose where they live and who they live with.

Countless people thrived in the freedom and opportunity they found in the community. But for others, says Wright, life outside the institution was a disaster. Hospitals were better prepared to handle people with multiple, challenging mental health problems than caregivers in the community (of course, the hospitals also had access to powerful drugs and physical restraints). “I’m not saying it was better,” Wright says. “But I think it was more straightforward.”

People with severe and difficult-to-manage disabilities have ended up in a variety of settings in the post-institutionalization era. Some get good-quality care and assistance, but others are cared for by overtaxed family members, living on the street or in homeless shelters or, like Shannon, living permanently in what is supposed to be a place for temporary treatment.

NEW BRUNSWICK PUSHED PEOPLE OUT of institutions in the 1980s and 1990s before the equivalent resources in the community were ready. They’re still playing catch-up. The province pays for programs and facilities, but also gives individualized funding for people to live in the community.

The department’s most community-oriented living option, the alternate family living arrangement (AFLA) program, amounts to adult foster care. People take one or two adults with special needs into their home, receive funding for their care, and live together as a family. To qualify, families have to pass a criminal record check and a scan of their prior contact with Social Development. Joy Sullivan says that Shannon went to live with such a family in late 2010, but the couple quickly realized they were unable to handle her violent behaviour. Within weeks they had her charged and sent back to Restigouche. Thomas says many people the department serves have needs that are too complex for the family placement program. That’s where residential care comes in. Sometimes called custodial or congregate care, it’s prevalent in the province.

In New Brunswick, care homes are licensed on a sliding scale from level one to level four, according to the amount of help residents need with daily activities such as eating, bathing, taking medication and getting dressed. A 2012 report from the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health says most of New Brunswick’s seven thousand residential care beds are in special care homes (levels one and two). About five hundred of New Brunswick’s residential care beds are higher- support spaces in community residences (levels three and four), which are still homelike but tend to be somewhat more institutional. (At last count, the total population of the province was just over 755, 000 people.) It is the department’s policy to make every effort to get people out of hospital settings and into the community if possible.

There has been an overwhelming need in New Brunswick for level four spaces, where people with serious medical or behavioural issues are cared for at a ratio of three clients to one staff member. In an oddball feature of this byzantine system, there seems to be a psychological barrier against going any higher than the number four. Sullivan says Shannon has been cared for at a level described as “four-plus” and even “four-plus-plus;” at times having two trained staff members assigned to care for her.

Every plan for level four care and above has to be individually approved by the department. A level four space in a community residence costs the department a maximum of $4,701.07 per month compared to $1,935 per month for a high-needs person in an AFLA family home placement (additional money is available to send the person to programming, such as a day activity centre). A month’s stay in the hospital at Restigouche costs the province in the neighbourhood of $9,000, not including doctors’ fees. When Shannon was little, Sullivan said she received about $430 per month to care for her, but Joy and Paul took a variety of courses that allowed them to qualify for more funding, and by the time Shannon left their home the family was getting about $1,000 per month for her care. The department, very occasionally, will set a high-needs person up in a home or apartment with round-the-clock supervision. The cost of such an arrangement can top $100,000 per year. Nobody from Social Development can comment on specific cases, so they couldn’t say why this has not been tried for Shannon. Social Development pays to send a handful of severely disabled people to costly residential facilities over the border in Maine, and has been working in recent years to get adults with special needs who are under sixty-five out of nursing homes.

Then, of course, there are psychiatric hospitals, which a 2005 article in the journal Psychiatric Services called the “setting of last resort” for people with severe, persistent and dangerous conditions who can’t be managed in the community. According to the Canadian Institute for Health Information, the average length of stay in a psychiatric hospital in the Picture Province is 207 days. The national average is eighty-one.

Trial and error might just be the only way to find Shannon a home that’s right for her. If someone is frequently being moved between different homes, it shows the department is working really hard to try to find them a placement.

In Sullivan’s words, it takes “somebody extra-special” to handle Shannon day-in and day-out. She’s unique, but her symptoms aren’t. Aggressive, inappropriate and violent behaviours are symptoms of many conditions, including brain injury, fetal alcohol syndrome and personality disorders. Those with mental illnesses such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder may lash out at people, property and themselves while in the throes of psychosis.

New Brunswick’s adult care system is chronically under-resourced, although no one from Social Development was able to put an exact number on the shortfall—either in terms of people who need to be housed or the money that’s needed to fill the gaps. Jacques Duclos, from Restigouche Hospital Centre, said that as of October 2014, there are at least ten people there who are perfectly ready to leave but don’t have anywhere to go. In late 2011, while many people waited for a supported place to live, three group homes in Saint John closed for financial reasons. In early 2014, a large special care home run by the Salvation Army closed because it couldn’t cover costs.

FOR HAROLD DOHERTY, making a simple phone call from his home in Fredericton is a difficult process. “Can you hear me okay?” he asks. “The static is likely on my end. Conor likes to pull the phone cords out. You can probably hear him now.”

I heard squealing and screaming in the background. Eighteen-year-old Conor Doherty lives with his parents, loves school and looks forward to spending time at Killarney Lake during the sum- mer. His mother adores him, although as she gets older and he gets bigger, she’s finding it harder and harder to deal with his meltdowns. Harold, Conor’s father, is a self-described “big mouth” lawyer who dedicates much of his spare time to advocating for his severely autistic son and others like him. He’s a prolific blogger on his website, Facing Autism in New Brunswick, and part of the Autism Society New Brunswick.

Some of his views are unconventional. Conor just can’t integrate into every aspect of mainstream society, Doherty argues. He says that he’s glad Conor is out of the mainstream classroom for most of the school day. New Brunswick’s current care system, he says, isn’t equipped to help his son. “The reality no one wants to admit is that some people just need to be institutionalized,” he says, but he describes the word itself as a loaded one.

Doherty insists only an expert with specific training in autism can handle Conor. And he maintains that the best setting for that will be residential care at an intermediate level somewhere between a hospital and a group home, a service he says has been “totally neglected” in recent years. Doherty rails against the “Community Living ideology” he says pervades the New Brunswick government. “It’s not based on evidence. It’s a philosophy.”

What Conor needs, his father says, is a safe place to live and treatment, not just basic personal care. Doherty has come up with the idea for a centre of excellence for autism based in Fredericton. He wants it to include a provincially funded residential home for autistic adults and a training centre that can certify group home workers from communities around the province.

Doherty brought up his idea at an Autism Society New Brunswick meeting I attended. Emotions ran high at the meeting as the conversation meandered from special education to housing to adult care. Four or five parents started crying in the middle of speaking. The society has opened a dialogue about adult care, but that’s as far as Doherty’s idea has gotten. Does he have any faith a centre will be built in time for his son to benefit?

“It has to,” he says.

IN ITS POSITION STATEMENT ON HOUSING, the Canadian Association for Community Living says adults with intellectual disabilities should be able to access apartments and houses from the mainstream housing market and receive disability supports through a separate system.

“In Canada today,” the statement says, “many individuals continue to be presented with options that do not support lifestyles of choice but rather assume that people with intellectual disabilities will stay indefinitely in the family home, or move into group home programs or other more institutional environments.” People shouldn’t be “placed” in a home, Community Living's statement argues; unless they personally choose to live there. And congregate homes should cease to be offered as a standard residential option. In theory, this means people who are able to live in the community will have the support to do so, and there would be money and community-based resources freed up for those like Shannon, who just can’t live independently.

Shannon’s disability sometimes limits her decision-making, but what she said in court about going to Miramichi is telling: she is able to articulate her desires when it comes to where she wants to live. Shannon told me she asked to go to Miramichi “because Restigouche makes a big stink out of everything, and at Miramichi they treat me with more respect.” And of course; she’s not sick. There’s nothing the hospital can do about her autism.

I called Shannon in October 2014. The hospital put me on the phone with her, no questions asked, and allowed us to have a private conversation. As Sullivan told me, Shannon is easy to talk to, although she speaks in clipped sentences and a flat, gruff tone. She understands that other people will be reading her story.

I ask her how she felt about living in Restigouche. Her answer: “I hate it. It’s boring.”

What does she spend her time doing? Not much. She says that she doesn’t like the activities the hospital offers, but doesn’t elaborate. She says she doesn’t get many “breaks.”

As for what she would prefer to be doing, she says that she wants to be closer to her family. She’d like to go out to eat with Joy and go shopping. She hopes maybe she’ll be moved to the CentraCare hospital in Saint John, just an hour away from the Sullivans. “They’re the only family I’ve got,” she says.

Paul and Joy call themselves Shannon’s family, but legally they’re not. “In her mind, we’re her parents,” Paul says. However, the Sullivans feel they don’t have the same access to Shannon as biological parents would. They considered adopting Shannon years ago, but were advised by a social worker that doing so could decrease the already-limited government support they received for her care.

There is no system to automatically appoint independent formal advocates for people with disabilities who have no legal family. Someone, say, who could help to explore what made Shannon happy in the specialized youth home and aid in finding a placement that fits some of those parameters. Community Living’s statement cautions against letting government agencies act on behalf of individuals. “Housing choices for adults ... are currently provided in a manner more geared to meeting the needs of the system rather than of the individual.”

In 2009, Provincial Court Judge Michael McKee released a report recommending sweeping changes to the mental health system, including an increase in “housing options with related treatment, services and supports for community living.” But four years of austere budgets and one change of government later, McKee called for an update, saying the lack of progress was “troubling.”

The province responded to McKee’s original report with a seven-year action plan to decrease the days spent in psychiatric units by 15 percent by 2018. An equivalent plan for people with disabilities emphasized that Restigouche should focus on acute care and recommended the province continue moving out long-term patients and transferring them to services offered at local community mental health centres. Around thirty patients were moved out in the last couple of years—Shannon was not among them. Making the rest of the transition happen is going to require the province to grow its community mental health services as well. The goal is to reduce the waiting list for those by 10 percent by 2017. The province also has an ongoing project that provides extra social assistance benefits to people who are released after an extended stay in one of the psychiatric hospitals. That will continue when Restigouche downsizes again soon.

Shannon says she has a court date in December 2014, so there’s a chance she may finally have left Restigouche when, around May 2015, it moves to a brand-new building with a modern design, a community-focused approach to care—and thirty-two fewer beds. “Our intention is really now to move people into the community. We are moving from a psychiatric institution to a more highly specialized psychiatric service provider,” Duclos says.

MARCOS SALIB has been a social worker for twenty years. He worked with Social Development before quitting his job to take a full-time position at the Canadian Union of Public Employees, representing and advocating for community care staff across New Brunswick.

To him, it’s no mystery why Shannon and so many others don’t thrive—the services for them are drastically underfunded. Twenty years ago residential care staff, who generally hold a one-year college diploma, made about double minimum wage, he says. Today, it’s unusual for them to make more than the provincial minimum of $10 an hour. Salib thinks that’s peanuts for a job that requires so much patience and stamina. “[The province wants] champagne service on a beer budget,” he says. “Why don’t you go and sit there, work with the workers, and be spit on, and be yelled at, and be threatened to be hit, be hit, be assaulted?” he says. “When you’re dealing with situations like that, you’ve got no other choice but to call the police.”

Getting law enforcement involved with people who will inevitably be found not criminally responsible is how someone like Shannon gets stuck in the cycle of hospitalization, community placement and criminal charges that disability expert Dorothy Griffiths calls psychiatric pinball. To Griffiths, a professor of child and youth studies at Brock University, the staff who call the police aren’t to blame; the problem is systemic. “You don’t just dump the person back if the same conditions are there that led to the offence,” she says.

Tim Stainton is the director of the School of Social Work at the University of British Columbia, and he researches the integration of people with mental disabilities into the community. He too cautions against harshly judging people who work in the entrenched and chronically cash-poor social services system. Many social workers feel stretched in two opposite directions for their whole careers, Stainton says. The interests of a social system, such as staying on budget and maintaining good public relations, don’t always line up with the interests of the client, which are supposed to be the first priority.

When asked about the funding issues, Salib’s response is passionate. “Don’t tell me that we do good work and it’s so important,” he says, bringing both hands down hard on his desk. “After a while, talk is cheap. Put the actions into it. Actions mean funding.”

Special care homes were given a $3.8 million boost in the provincial budget last year. But leading policy and research organizations in the field argue that cash injections here and there don’t get people with special needs any closer to real independence and autonomy, and they don’t change the structure of the system. “Restigouche has become a catch-all,” Salib says. “We’re going to dump you there because we don’t know any more what to do with you.”

THE SULLIVANS still have kids who live at home, and have also taken in Joy’s elderly mother. The trip to northern New Brunswick to visit Shannon in the hospital requires an overnight stay; they don’t do it very often. But in 2012, they packed up a few gifts, including a book about outer space, one of Shannon’s current obsessions, and began the six-hour journey to the hospital to celebrate Christmas with her. Last year, they made the same trip again, but a storm added hours to the lonely drive.

Restigouche is a sprawling structure built of dark red brick; it opened in 1954. Looking quintessentially institutional, it sits on the outskirts of a small, picturesque Francophone town. To imagine what life is like there, Sullivan says, “Envision an old mental hospital.” She says Shannon gets very little activity or stimulation. “They do let them out in the yard once a day, like they would if you were in prison.”

Sullivan talks to Shannon on the phone several times per week, and says the young woman seems to be reasonably healthy and lucid. “She calls us almost every day. She just wants to hear a voice and have somebody to connect with,” Sullivan says. “She’ll tell me what’s going on and if she’s having trouble holding it together. And I’ll try and talk her down. She’s not happy in any way, shape or form. She paces like a rat in there. She doesn’t have anything to do.”

On a good day, Sullivan can still get a laugh out of Shannon. They’ve done their best to keep her spirits up. As she does for all her children, Sullivan has made Shannon a “life book” of their time together. Shannon’s is with her at Restigouche, but Sullivan shows me a thick book she made for one of their other children.

“This is your life!” declare colourful letters on the cover. Each page has a different theme. Birthdays and holidays are commemorated with photos, stickers and scrawled notes. Shannon’s album, Sullivan says, is even bigger. She holds open her hands a foot apart and laughs.

“There are lots of things in there that I wrote to her, that I’ll read to her some time,” she says. “I explained it all out to her—why she’s not here, and about mental illness.”

That she is not legally considered Shannon’s mother has been a source of frustration and anguish for Sullivan over the years. But she says that she went from mad to irate four years ago, when Shannon had already been in Restigouche for a few weeks. Sullivan was able to get a letter about Shannon to the minister of health.

The letter contained a brief history of Shannon’s life up to that point and a plea for the department to find a placement that would meet her needs. Sullivan wrote that she thought Shannon should not be sent back to the alternate family living arrangement placement where she had been living, because the family did not have the training to deal with her violent episodes.

“The minister’s response was to get [the regional manager] to call me,” Sullivan says. “She told me that they had convinced this home to take her back.” When Shannon was in the hospital for all those months—from around Christmas 2010 to June 2012—and the Sullivans thought she was in a family placement, Sullivan says she backed away because she was told to. “I don’t have any legal rights to that child. So I’ve always tried to work with [the department] because I want them to know I’m a team player,” she says. Sullivan says a social worker told her that Shannon was so attached to the Sullivan family that they needed to cease contact for a while to give her time to settle into a new home. “I said okay. I’ll do that if you honestly think that’s what best for her. This isn’t about me. This is supposed to be about Savannah. It’s not that it’s going to break my heart if there’s no communication between us. I’m a big girl.” Sullivan says she was “hoping above hope” that because she hadn’t heard anything, everything was going well. But, of course, it wasn’t. Sullivan doesn’t know if the particular public servant she was speaking with knew that Shannon never in fact ended up going back to her former placement and was still in the hospital.

Sullivan read in the Saint John Telegraph-Journal that Shannon would be back in court on June 5, 2012. So on that day she drove an hour from St. Andrews and watched the proceedings as the young woman she considers her daughter sat in a wooden prisoner’s box with uniformed sheriffs guarding her. The hearing didn’t last long. The judge decided Shannon should go to a home arranged by the Department of Social Development. She went to the community residence in Saint John—which Sullivan called a home “they pulled out of a hat.” Outside the courtroom, Sullivan and Shannon embraced, and they walked together towards the court desk.

According to Sullivan, Shannon asked her, “Mum, can you take me to my new home?” to which Sullivan replied that she would not be allowed, but promised that she would try to find a way to see her. That’s the scene Sullivan described in a scathing letter to the same regional manager she sent via email:

What I feel now, I can’t begin to describe to you, which is why I write, because I can’t even talk about this without breaking down. The thought of … placing a child (yes, in an adult body) in a mental institution for a year and a half, where she spent two birthdays and a Christmas, without a word, letter, phone call, or visit from her family or loved ones is beyond my comprehension. For anyone in this country, in your care, to believe that no one cares or loves them is in my mind inexcusable, and the fact that no one even showed up to her court date I’m sure reinforced that to her loud and clear … I ask you as a mother, and as one woman to another, please do not turn your back on her again.

Four days later, Sullivan received a polite reply:

“Thank-you for connecting and I am just getting to some of my emails. I was in Fredericton last week and again most of this week. I will connect with Savannah’s Social Worker to discuss your request to maintain contact. I understand that Savannah has settled in well in the Adelaide home and with [a worker at the home] knowing her previously there is already a connection established. I will reconnect with you again this week Joy.”

The manager promised to follow up, and she did a few days later. She reiterated by email that she would talk to Shannon’s social worker about Sullivan’s request to stay in touch, and said the department’s goal was to provide Shannon with a placement that gave her quality of life. She also said the transition to the new home was going well.

That placement lasted only a few weeks. Shannon was charged once again, and spent another eight months in Restigouche.

Social Development is working to move to a more inclusive system of supporting people with developmental and mental health disabilities. When they’re making a case plan, social workers sit down with a team of people—the person being served, agencies such as community mental health, the family, and anyone the disabled person wants at the table, even if they’re not related by blood. But Sullivan wanted to be informed when Shannon was moved to Restigouche. That’s private health information. That’s confidential.

The department calls its approach “person-centred planning.” To the extent possible, the person with a disability is supposed to be able to freely choose where they live and how they spend their days. Even if someone is nonverbal, the department does its best to use resources to help interpret what they’re trying to say. This philosophy is in line with changing global attitudes about the rights of people with disabilities and the 2006 UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. But for some reason, it didn’t seem to work effectively in Shannon’s case. When doing case planning, it’s not atypical for social services systems to involve advocates who don’t have any formal legal standing in a person’s life right up “until things get sticky,” says Tim Stainton, the social work professor. Sullivan thinks that’s what happened to her family: things got sticky, and they were shut out. Shannon desperately wanted to be in touch with the Sullivans during that year and a half she spent alone in the hospital, and her wishes weren’t respected.

Shannon moved from Restigouche into a placement in rural New Brunswick. This time, to Sullivan’s relief, she was invited to meet with Shannon’s care team and the new family before Shannon was discharged from the hospital.

Sullivan was ecstatic about the location of the new home, which was much closer to them than Restigouche with plenty of opportunities for Shannon to get fresh air and exercise. The Sullivans visited Shannon all through that spring and summer, and communicated regularly with the family, but they tried not to call too much. The last time Sullivan telephoned, Shannon’s caregiver said she’d been acting up—getting obsessive and using threatening language. Several weeks passed without any word from Shannon. Then Sullivan called to ask when she could come for a visit. The woman said, “Didn’t you know? She’s not here.” In July 2013, Shannon was sent back to Restigouche.

Sullivan is afraid Shannon may spend her life there, but she still holds out hope that the woman she considers a daughter will find a safe, happy place to live as independently as possible. She admits she has looked over the department’s shoulder through this whole ordeal, even though her motivation was only to look out for Shannon’s best interests. She doesn’t want to hover. She sees herself as Shannon’s personal Nanny McPhee. “I said to her, ‘You remember that story? I’m there when you need me, but if you just want me I might not be right there!’” But right now, with her future uncertain and her life contained to a psychiatric hospital, Shannon still needs the woman she calls mom.