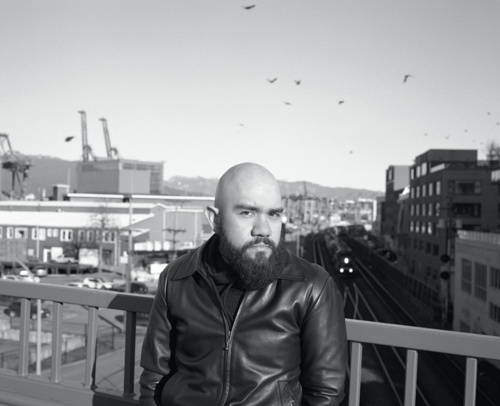

Hector Diaz came to study English in Canada just weeks before VEC shuttered for good.

Photography by Naveen Naqvi

Hector Diaz came to study English in Canada just weeks before VEC shuttered for good.

Photography by Naveen Naqvi

The Language of Profit

Private language schools have always struggled to balance educational needs with profit. Erika Thorkelson investigates how these tensions boiled over at one Vancouver school, leaving students and teachers out on the street.

When Hector Diaz decided to study English in Canada, he thought he was doing everything right. The thirty-three-year-old from Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, had heard of people immigrating to the United States illegally, but he was determined to follow the rules. He was finishing a master’s degree in marketing and administration, and he hoped immersive language training would widen his career options. Juárez is just a hop over the border from Texas, but Diaz wanted an English accent without a drawl—something neutral and easy to understand—so he chose Canada, and then narrowed in on Vancouver. He’d heard stories of the city’s natural beauty, mild weather and kind people.

A year before he left Mexico, Diaz applied for a tourist visa. His university’s travel office recommended a number of schools, their websites featuring photos of snow-capped mountains and happy students. He settled on Vancouver English Centre (VEC), a large school with a good reputation and middling fees. He imagined himself finding a job in Canada someday, applying for citizenship and staying forever.

Diaz wasn’t rich. To pay for his airplane ticket and the $6531 tuition for his five-month study period, he sold his car and a few other possessions. He arrived in the city on June 19, 2016, and moved immediately into a homestay in South Vancouver that the school had arranged for him. He could hear the family’s baby crying from the room he shared with another international student, but the inconvenience seemed worth it. The next week, Diaz started classes at VEC, and for a few weeks, everything went as planned.

It’s difficult to measure exactly how many students enroll each year at Canadian private language schools because students who stay for under six months, like Diaz, don’t need to apply for a study permit. The best available statistics come from Languages Canada (LC), a large private organization that represents 226 schools nationwide. LC estimates that roughly 133,910 students—including students who study for a longer period than Diaz—enrolled in their schools in 2015. The vast majority of these students studied in British Columbia and Ontario, and the top five countries of origin for English-language programs were Brazil, Japan, South Korea, China and Saudi Arabia. The economic impact of this influx of students is staggering: LC’s member schools collect around $1.5 billion in tuition and living expenses per year.

The number of teachers who work in the ESL industry is even more difficult to calculate. Language teaching tends to be a transitory industry; workers range from full-time, career teachers at big schools to private tutors who meet with students for a few hours a week in downtown cafés. Again, it’s helpful to turn to LC: their member schools employ almost 4500 teachers across Canada, and around nine hundred of those teachers are employed at Vancouver-area ESL schools. Teachers aren’t the only ones who rely on the industry; schools also employ administrative staff and marketers who work with international agents all over the world, while homestay families host the students, using the extra revenue to make ends meet.

Yet this industry usually goes unnoticed by media and the larger culture, even in its biggest markets, until something goes terribly wrong. There have been a few disasters involving homestay kids in Vancouver over the years—stories about accidents, binge drinking, disappearances, fly-by-night visa mills and even deaths. But no event in recent memory has had repercussions as conspicuous and far-reaching as when VEC locked its doors last August after a protracted labour dispute with its teachers. Making international headlines, the closure left about six hundred students on the street and laid bare tensions at the heart of this multi-billion-dollar, multinational industry.

By all accounts, VEC was a solid institution for almost two decades. Opened in 1993, by 2016 it was one of the longest-running private language schools in Vancouver. It was located in Yaletown, which was a warehousing district pre-Expo 86, but has since gentrified into a neighbourhood of minimalist shops and high-end gastropubs. Taking up the entire ground floor of a cream-and-grey converted warehouse, VEC’s facilities included a privately run café, four computer labs and fifty classrooms connected by halls named for tourist hotspots around the city.

VEC’s owner, Kenneth Gardner, wasn’t an educator. Instead, he was an entrepreneur who recognized an opportunity. International travel costs were falling and visitors from Japan, China and South Korea flooded across the Pacific Rim on direct flights. Tourists from Mexico, South America, Saudi Arabia and Europe followed, drawn by the maturing industry, the lower Canadian dollar and the rise in Vancouver’s international profile.

A mustachioed man in late middle age, Gardner poses on his Facebook page with groups of employees and students, smiling in the sun on the school’s roof or at Kitsilano Beach with the green North Shore mountains in the distance. No matter how casually everyone else is dressed, Gardner is always in a suit.

When VEC was new and there was little competition, Gardner easily navigated the tension between ensuring students received a quality educational experience and keeping the school profitable, according to Christina Labarca, who worked at VEC from 2000 to 2012. But as the industry grew from a few small schools to a bustling multinational powerhouse, private language schools like Gardner’s became increasingly vulnerable to pressures from the global market. A change in visa regulations or an economic slowdown in South Korea, Brazil or Saudi Arabia could send shockwaves through the whole industry.

Over time, schools found themselves juggling the needs of students who come to Canada for fun—a sort of study holiday—with those, like Diaz, who were seeking concrete skills and professional development. A single class might have students from ten different countries, some as young as thirteen, studying alongside people who could be their grandparents. Languages Canada estimates that in 2015, fifty thousand students, more than a quarter of the people registered in its schools, intended to go on to post-secondary education in Canada—meaning that private language schools provided not only an important point of introduction for short-term visitors, but also a bridge for those who intended to stay long-term.

According to Labarca, who worked first as an instructor and then as academic director, Gardner worked alongside the teachers to balance business and educational needs in the school’s early days. He was “very respectful,” she says, when she went to him to advocate on behalf of the teachers. The two would work together to find space in the budget for competitive wages and professional development opportunities to keep the teaching staff sharp and stable.

The result was a relatively healthy environment for both students and teachers. Endie Tompkins, a teacher who came to VEC in 2009 on the recommendation of her Teaching English as a Second Language (TESL) certification instructor, first visited the campus during an international celebration where the entire school was turned over to students to showcase their individual cultures. “They brought in food from their home countries and let them decorate,” she recalls. “I remember running across my [TESL instructor] and he said, ‘This is what a language school is supposed to be like. This is why we do this.’”

Teacher Joy Singh was hired in July 2001, only days after arriving in Canada as a new immigrant from Oman. Though the industry is notorious for discriminating against non-North American and non-white speakers of English, staff at VEC were welcoming. “I think it was helpful that I’d been teaching at the British Council,” she says, with self-deprecating humour. “They probably thought my English wasn’t all that bad.”

Singh went on to be one of the most popular teachers at the school. She taught prep classes for the legendarily difficult International English Language Testing System (IELTS) exam, one of the few tests accepted for entry to Canadian universities and one of only three accepted by Canadian immigration. Students from all over the world came to the school specifically to take her class. If it hadn’t been for Gardner’s direct intervention, though, Singh’s tenure may have lasted no more than a few weeks.

Less than two months after Singh was hired, the September 11 terrorist attacks shut down the tourism industry across North America, forcing many schools to lay off even more staff than usual during the annual autumn slowdown. As one of the newest teachers, Singh was the first let go from VEC. She wrote Gardner a note, thanking him for the opportunity to work with him at the school. “I explained that since I’m a new immigrant, I’m not eligible for EI, and I would be very happy to teach again whenever the opportunity arose,” she remembers.

Gardner seemed touched by Singh’s old-fashioned politeness and instructed the then-director of studies to get her in front of the next available class. “I’ve never forgotten that kindness,” Singh says. “That’s why I was all the more perplexed by his behaviour as the years progressed.”

All the teachers I spoke with pointed to 2012 as a watershed moment in their relationship with school management. Labarca, who became academic director in 2006, says it began when a former student was hired to the IT department and given more authority around the school. “His view on the business and my view were extreme opposites,” she says, choosing her words with care. (I reached out to the former student through Gardner, but he did not respond to my inquiries.)

According to several people I interviewed, a new feeling of distrust between teachers and management took over the school. Surveillance cameras appeared in the office and the teachers’ room—they were supposed to be for security, but some believed they were there to keep an eye on staff. Certain websites were blocked from computers, including ones for the University of British Columbia and Simon Fraser University, which Labarca used for professional development research. When she went to Gardner, he said that she would have to speak to IT for permission to access them.

For Labarca, the last straw was the day she went to Gardner over a computer issue and he let loose a “tirade of accusations” about her attendance at work. “He basically accused me of stealing time and money, and of not being in the office when I said I was,” she says.

Labarca believes that the school had been tracking her computer, not taking into account that she might have had other business around the school that would take her away from her desk before she had a chance to log in. Gardner apologized after she rebutted his accusations, but the relationship had soured. In June 2012, Labarca left the school.

While new flatscreen televisions and other expensive equipment began to replace older models in the corridors, starting wages for new employees began to drop. Kim Fissel, who joined the teaching staff in 2012 on the recommendation of her now brother-in-law, started at $20 per hour, which is roughly in line with the industry standard. According to multiple accounts, those who came after received only $18 per hour, and paycheques started showing up late and filled with errors.

Then a new program catering to primary-school children called Skills 4 Kids was introduced. Fissel recalls that two teachers were hired at starting wages of $12 and $14 an hour, respectively. She points out that these wages were less than you would make working at a chain coffee shop. “Twelve is not even as good as Starbucks because you don’t get tips,” she says.

Gardner refused to speak in person, citing ongoing legal issues. By email, he argued these wages “were as high as possible in relation to [their] competitors.” He pointed to a BC government website that estimates wages for Early Childhood Educators (ECE) and assistants as ranging from $11 to $24.84 per hour. But those wages cover all of British Columbia, including areas with a much lower cost of living, and the low end of ECE jobs only require a three-month diploma rather than a university degree, which both Skills 4 Kids employees had. In a city with a high—and rising—cost of living, the pressure on VEC staff was beginning to turn into serious labour unrest.

In 2014, things came to a head when Gardner announced that he would be purchasing an iris scanner to track employee attendance. The equipment came from a company called Easy Clocking whose website promises to “eliminate employee time theft.” The biometric information it collected was to be sent to the company’s US headquarters for processing. In his email, Gardner says VEC purchased the system “to improve back-end efficiency because it provided an interface with our payroll service.”

Teachers, already frustrated by the school’s austerity measures, considered the purchase frivolous and the technology Orwellian. “It was a complete invasion of my privacy,” Singh says. “I didn’t want the American government to have my biometric [information].”

Singh did some research about BC privacy laws and wrote a letter to her colleagues. The letter found its way to Gardner. On Tuesday, November 25, he called Singh into his office and told her they were letting her go after thirteen years of service. “I said, ‘Ken, you have to understand, whatever you do in this lifetime, you pay for it in this lifetime,’” she recalls. As she left the office, reality sunk in: at the age of fifty-four, she was back on the job market.

By this point, VEC teachers had already been in contact with the Education and Training Employees Association (ETEA), the union that represents several of the city’s private language schools under the umbrella of the Federation of Post-Secondary Educators (FPSE). Gardner’s choice to fire Singh strengthened their resolve.

One afternoon, Kim Fissel was sitting in a classroom when an older teacher walked by and asked her where her brother-in-law—a fellow teacher—was. She joked that she didn’t know—he’d married her sister, not her. The older teacher said, “You’ll do,” so Fissell followed him to a staff meeting with the union where she quickly became caught up in the process. She later joined the bargaining team and was elected interim president of the school’s union chapter.

The ETEA had been established in 1995 in response to a pay dispute at another large downtown private English school. In VEC’s case, they knew exactly what to do. In British Columbia, there are strict rules both employees and management must follow during a union drive. On one side, the union is not allowed to conduct meetings during business hours without employer consent. On the other side, management must continue “business as usual.” VEC would not be permitted to threaten or intimidate union organizers, nor would they be allowed to fire employees without written permission from the Labour Relations Board (LRB).

Union officials took Singh to the LRB on Friday, November 28, and she was back at work by the following Monday—the same day teachers voted to join the union. The motion passed thirty-eight to two, with one vote disqualified, and VEC was certified as ETEA Local 9 on December 1, 2014.

Bargaining began in earnest in April 2015. Management, including Gardner, the academic director, and a couple of human resources staff, met with the union bargaining team on twelve different occasions, each time budging a little on basic demands around preparation time, pay, vacation time, the notorious iris scanner and a raft of other issues.

ETEA president Kevin Drager, who agreed to speak on behalf of the union though he did not personally attend the sessions, says that bargaining processes are often “an education” for employers and employees. In this case, he believes the process was hampered by Gardner’s financial inability to secure counsel who might have guided him through the intricacies. In the LRB complaint, the union described Gardner as “bargaining in bad faith,” though this is no longer their official position. “There was cancelling meetings for bargaining dates, not responding to emails to set things up, walking out of bargaining,” says Drager. “We had to clarify—are you actually walking out?—and we had to backtrack.” For his part, Gardner characterises the teachers’ wage demands as unrealistic; he also says they were unwilling to take into account the preparation pay they were already getting.

The relationship between teachers and management was strained, but both sides had vowed to keep it out of the classroom. Hector Diaz, for example, who started classes over a year into the bargaining process, had no idea he was walking into a labour dispute. He began taking classes in job skills and hospitality, and getting to know his classmates. From his perspective, the dispute had not poisoned the school’s atmosphere. “It was a big school, always full of people, a multicultural environment,” he says. “I felt so glad to be there.”

On June 22, 2016, fifteen months after they’d begun negotiation, just days after Diaz first entered VEC’s doors as a student, the teachers held a strike vote. Rather than walk out of VEC immediately, Local 9 applied for public mediation. Trevor Sones of the LRB acted as mediator during three long bargaining sessions on three separate days in July. Fissel remembers the last day of mediation as a “marathon” session. “I was in the room for [over] fifteen hours until 12:40 at night,” she says. “We had sent over, not our final proposal, but we were getting close.”

That’s when the process broke down. Though Sones asserts that a “multitude of issues” had been resolved through mediation, he also lists six key issues as unresolved: prep time, statutory holidays, vacation, sick leave, wages and the term of the agreement. After a ten-day cooling-off period, throughout which the union tried to coax Gardner back to the table, the teachers took to the picket lines.

During the four weeks of the strike, Hector Diaz met with Gardner three times, the first time alongside the entire student body and subsequently in a group with other Spanish-speaking students. Each time, he says, the school owner seemed increasingly disconsolate. Classes would start again soon, Gardner promised, and they’d make up for the time they had lost.

While the teachers picketed, administrative staff struggled to keep students calm. One employee on the administrative side who asked not to be named, citing professional concerns, says he witnessed school marketers being dressed down by angry parents. “They just had to sit there and absorb all this nasty energy,” he said. “They were just thrown out there unprepared.”

Teachers discouraged students from crossing the picket lines, suggesting instead that they demand refunds for the classes they’d bought. This, Gardner claims, caused irreparable harm to the school’s business during peak season.

Meanwhile, on the picket line, the teachers remained optimistic. They walked in shifts carrying signs that said “Teachers Deserve a Living Wage!” and “GET BACK TO THE TABLE!” It wasn’t the first time an ETEA local had gone on strike. The previous summer, teachers from Pacific Gateway International College had spent two weeks picketing before they ratified their first collective agreement. Concurrent to VEC’s dispute, Hanson International Academy, a small private career college in the suburb of New Westminster, was engaging in a strike of its own. They became Local 11 in July 2016 and held their ratification vote on Labour Day.

Labarca, who had left the industry to form her own business, was less optimistic. “When I heard they were on strike, I was frightened for the teachers,” she says. “One of the things [Gardner] had openly stated for years was that if the school unionized, he would close it.”

More than three weeks after the strike began, on August 23, Gardner finally agreed to return to private mediation. They were scheduled to start later that week.

On the morning of August 26, Fissel caught a ride to the city with the union lawyer and her brother-in-law. She arrived to find chaos outside VEC. The school’s glass doors were locked, and a taped-up note addressed students, staff and service providers. It read: “The school is closed and we do not expect to reopen. We apologize for any problems this might cause. Unfortunately, this was the only possible course of action. We thank you for your support and patronage over the last twenty-three years. Sincerely, The Management.” With that, around six hundred students, forty teachers and a two dozen admin staff were abandoned to fate.

A handful of administrative staff corralled the primary school children who were still being dropped off for school by homestay families—Gardner had sent an early-morning email announcing the closure, but many people hadn’t checked their inboxes yet.

Fissel gathered with about twenty other teachers in nearby Yaletown Park, a square of concrete decorated with a rusting train car, before they made their way to the Federation of Post-Secondary Educators offices to be debriefed by union staff. “We had a little cry,” Fissel says. “We got some questions answered.”

As one of the older students, Hector Diaz took it upon himself to speak to the media, appearing on CBC News and in Metro News. He wrote letters to everyone from Premier Christy Clark to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, asking them to do something to support his young, vulnerable fellow students. Not knowing where to turn, other students poured their frustration onto the school’s Facebook page. (“THIEVES,” wrote one former student. “[T]his school is a fraud. [G]ive us our money back.”)

Monica Velazquez Lemus’ family had paid the last of her niece’s tuition on August 17, in the middle of the strike. The teen never attended a single class, and never received her promised refund. A twenty-seven-year-old student named Yong Il Shin—who goes by the name Aaron—had three weeks left on his contract with VEC, which amounted to about $1000. When I met with Fissel at the end of August, she told me there were still students arriving in Canada to start classes at VEC.

After meeting with Fissel at a downtown coffee shop popular with English teachers and students, I went to visit the school myself. It was empty, and the lights were off. Through the ground-floor windows, I could see that some staff cubicles had been cleaned out, but others still had calendars and computers, as if staff were about to return from holiday. The letter from management was still where it had been taped. On the wall across from it, someone had posted another letter: “We want our money back as soon as possible. Refund our money. [W]e payed [sic] a lot for nothing. Sincerely, [t]he students.”

A young woman in a black hijab stood in VEC’s doorway, speaking rapid Arabic over the phone and waving her finger in the air in irritation. She was reticent to go on record, but eventually told me she’d studied at VEC five months earlier and had come back to get her certificate—the piece of paper that proved she’d completed her studies. In October, she emailed me to say she’d returned home empty-handed, which made it difficult for her to get a job. If I could do anything to get it, she wrote, she’d be thankful. I suggested she contact Languages Canada, but the organization could do nothing for her—they had no access to school records.

To this day, Gardner insists that the closure of VEC was the fault of the union. “The extended strike had been financially choking the school for some time,” he explained over email. “It was purely coincidental that the school closed the day before the second [round] of mediation was scheduled to begin.”

But Fissel and Drager believe that the strike was only one of a number of pressures VEC was facing near the end. The school’s Yaletown rents would have been astronomical, and the federal government had recently cancelled a popular language co-op program for international students that allowed students to do six months of study followed by six months of work experience, cutting off a big source of revenue for the school.

On top of that, in 2016, the provincial government had instated a requirement for language schools to meet student assessment benchmarks and curriculum standards set by the Private Training Institutions (PTI) branch if they were to continue accepting students for six months or longer. Meeting benchmarks meant having a clear rubric for passing and failing students. At a for-profit school, failing a student can mean losing a customer, something smaller schools have historically been reticent to do.

At some private English language schools, an entire class might simply be made up of handouts a teacher downloaded from the internet. While VEC had a set curriculum, it had not yet been set up to comply with PTI standards; to do so would have meant an investment of time and money to revamp that curriculum and demonstrate its effectiveness. In his email, Gardner, who has gone on record against government intervention in the industry in the past, called the process “onerous.”

Languages Canada director of member services Linda Auzins says that VEC had quietly let their membership lapse for lack of payment of dues on June 28, 2016, more than a month before the strike began. “The strike was probably the straw that broke the camel’s back,” she says. “But I think the camel was already hurt.”

Union head Kevin Drager says this was confirmed during January’s LRB proceedings when Gardner was compelled to release the school’s financial statements for review. From those documents, an FPSE accountant found that the school owed approximately $1.4 million before the strike began, which would explain why it wasn’t able to weather the three-week closure.

By November 2016, the VEC Facebook page, which Gardner still administered, had been scrubbed of complaints from students and international agents. Many of the students, teachers and administrative staff were still dealing with the fallout of the school’s closure.

To mitigate the effects on the reputation of the larger industry, Languages Canada had asked other member schools to take in VEC students without charging additional fees. Auzins, who organized the moves herself, says many saw this deal as a win-win—having the extra students didn’t cost a lot, and students could go on to purchase more classes. Students who paid after June 28 or were owed money for homestays, however, were out of luck.

Administrative staff had melted into other schools, though they were still owed thousands in back pay and vacation time. Under the Wage Earner Protection Program, they could have applied for compensation if VEC had declared bankruptcy—but it had not.

Teachers were doing what they could to scrape together a living. Autumn is a bad time to be out of work in the language tourism industry, as the wave of summer students ebbs and tourists arriving for ski vacations don’t usually appear until after Christmas. Fissel was juggling substitute teaching gigs at four different schools around downtown while Singh was splitting her time between a couple of schools to make ends meet.

More than anything, Singh expressed disappointment at the way her former employer reacted to the union drive. Her last communication with him came in September, when he sent her a pair of profanity-laden emails blaming her and her “followers” for everything and telling her to “rot in hell.”

“Ken Gardner was a very good human being once upon a time,” she said. “There were so many times I’d gone to him. He’s given free tuition to students who I said really didn’t have money. He helped out. I just don’t know what went wrong.”

None of the teachers I spoke to expressed regret over the choice to form the union. In fact, Fissel believes that the union has made the process of dealing with the closure easier than it would have been otherwise. The ETEA has helped them make complaints to the Employment Standards Branch and get EI payments; aided the teachers in putting together their labour board complaint, which was scheduled to be heard in January but has been held in abeyance while the union attempts to petition VEC into declaring bankruptcy; and created a small hardship fund made up of donations from other FPSE locals to help out teachers in dire need. “As sad as I am that my school’s gone,” Fissel says, “I’m delighted and astounded about how the union continues to support us.”

Whatever the immediate cause, the closure of VEC was not simply the result of a series of poor business decisions or unrealistic union demands. It grew out of an identity crisis at the heart of the industry: are these schools about education or profit?

Many within the industry have long argued that self-regulation would solve every issue. This has, to an extent, been effective. Before Languages Canada, the quality of education in these schools was uneven—some teachers had TESL certificates, many had no training at all. LC introduced standards for curriculum, assessment and course structure to make the quality of classes more predictable and ensure that marketing materials accurately reflected what was available at schools. But membership in the organization is not compulsory; smaller schools can simply decide to forgo the expense, as VEC did near the end, leaving students vulnerable.

The BC government’s regulation scheme offers similar guarantees to protect students, but that system only applies to students attending for six months or more, and the government regulates on a complaint basis. A school like VEC could continue to offer classes to longer-term students as long as no one alerted regulators. Even if students were aware of the regulations, few would have the language skills to fill out a report.

Neither of these regulatory models offer much in terms of security or support to the teachers who shape student experience. The language tourism industry has always had a large number of short-term workers—new university graduates with plans to move on to other careers or who are looking for experience before travelling. But there are many who have made teaching English a long-term profession. Some instructors had been at VEC for twenty years. As the market matures, it’s easy for some schools to see these experienced teachers as a liability rather than an asset. Owners don’t see the late nights marking exams or the research needed to elucidate the finer points of English grammar. Expenses like preparation time, curriculum creation and professional development are seen as budgetary burdens rather than integral parts of effective pedagogy.

At VEC, Gardner saw the union as an all-out assault on his business, but to the teachers, it represented a chance to have a say and a little stability. It’s impossible to know whether mending that rift would have saved a school that was already so far gone. But the lesson for the larger industry is clear: a fun atmosphere and flashy technology is no longer enough to keep Canadian private language schools alive and competitive—our schools must offer stability and reliable, high-quality education.

In the end, it’s the students who take the brunt of the industry’s inability to reconcile its educational responsibilities with its business needs. When I caught up with Hector Diaz over Skype in early November, just over two months after the school’s closure, it was clear that, despite everything, his speaking and listening abilities had improved. We spoke early on the evening of the US election, when Hillary Clinton still had the lead, and he’d been watching with interest and anxiety alongside the rest of the world. “It’s so important because I consider Canada, US and Mexico like brothers,” he told me.

With the help of Languages Canada, Diaz had started at a smaller downtown school in September. VEC still owed him roughly $5000 for the five months of classes he missed because of the strike and the closure. He’d tried everything he could think of to get the money back. Eventually, he went to the Mexican consulate, who put him in touch with a lawyer who suggested a class action lawsuit. The lawyer required a $5000 retainer to get started, so Diaz began petitioning his former classmates—if he could gather just one hundred of the approximately six hundred students who’d been affected, they’d only need to contribute $50 each.

Many said they supported his cause, but only twenty offered to put their money where their mouths were. “We all together were affected, so what about your help?” Diaz says, frustration seeping into his usually cheerful voice. “Finally, I just had to leave the fight.”

Next, Diaz went to a pro bono lawyer hoping to take Gardner to small claims court, but he couldn’t understand the paperwork the lawyer asked him to fill out. Instead, he decided to focus on his courses; this would probably be his last chance to be immersed in English for a while. Even after all he’d been through, he still believed that language proficiency was the key to finding his way back to Canada. He left in December.

Over Skype in November, the last time we talked while he was in Canada, Diaz showed me a couple of books he had been reading. One was Blink by Malcolm Gladwell—it was the first book he had been able to read in English. He was elated by the progress. The other, Man’s Search for Meaning by Victor Frankl, he was reading in Spanish. Frankl’s journey through Auschwitz, though obviously much different from his own journey, was proving a great inspiration to him through the tough times. “You have that choice to suffer or to learn,” he said. “I think that this experience makes me a better person. A Canadian man stole my money, but I can’t generalize. I think Canadian people are people who are kind.”