Ontario Inspector of Prisons and Public Charities.

Ontario Inspector of Prisons and Public Charities.

Incorrigible Women

How a 1948 riot helped end a special hell for Canadian women.

The air was electric inside the Andrew Mercer Reformatory for Women on the morning of June 25, 1948. The night before, a seventeen-year-old inmate had been carried off by guards after attacking a “squealer.” They were escorting her to solitary confinement, known as “the hole,” when several inmates heard the crashing sounds of a scuffle. Rumours quickly spread about what had happened, and prisoners came to believe that staff had thrown the teenager down a flight of stairs. After matrons threatened them with a leather strap, so the story goes, inmates began making plans—quietly—to protest.

They worked quickly. The next morning at breakfast, roughly a hundred prisoners filed silently to the round oak tables that filled the spacious dining hall. Perched on an observation deck at the head of the room was the Mercer’s long-time superintendent, Jean Milne. After Milne said grace, the inmates took their places and ate a simple meal of bread, porridge and black tea.

Then, they demanded the seventeen-year-old be immediately released from solitary. When Milne balked, the inmates began a sit-down strike, refusing to proceed to their assigned daily work. One matron’s attempt to end the protest was met with escalation: inmates began throwing plates and mugs through the dining room windows, and someone pulled a fire alarm. Milne ordered staff to call the provincial legislature for help. Soon, over one hundred municipal and provincial police officers found themselves rushing to one of Toronto’s most infamous institutions.

The Mercer Reformatory was built in the 1870s with good intentions. Named after a lawyer whose $100,000 estate funded construction, it was the first dedicated women’s penal institution in Canada. The imposing red-brick Gothic structure, built to house up to 196 inmates, was located near King and Dufferin in Toronto’s west end, down the street from the men’s Central Prison. The Mercer was constructed in response to emerging ideas that “fallen woman,” previously considered irredeemable, may indeed be salvageable—prior to its opening, female convicts had been housed separately from the men in the Federal Penitentiary in Kingston in a notoriously harsh atmosphere that reformers increasingly saw as unsuitable for female rehabilitation. Mixing between prisoners of the same sex was considered bad enough, but between those of the opposite sex, it was, according to prison reformer John W. Langmuir, “painful and repulsive in the extreme.” Women, it was assumed, were more susceptible than men to the corrupting influence of environment, necessitating their being removed to an entirely separate facility.

But as the Mercer’s prisoners would learn, special treatment didn’t necessarily mean better treatment. A curious mix of evangelical Christianity and pseudoscience gave the Mercer its underlying maternal-style discipline: virtuous, well-meaning, middle-class women had a duty to save their sisters living in sin, and the sciences provided new tools for doing so. Daily operations were overseen by a female superintendent who reported annually to the provincial government. Beneath her worked a team of guards called “matrons” and a revolving cast of medical staff and charities. Reformers medicalized undesirable behaviours as “delinquency,” a curable, if stubborn, affliction; like men, inmates performed mandatory hard labour, which, through repetitive domestic tasks, was intended to force atonement for past behaviours, saving inmates’ souls in the process.

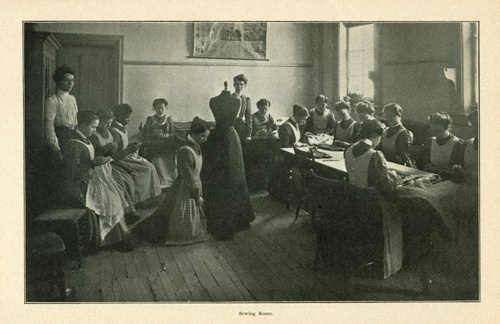

The Mercer’s prisoners woke up inside their powder-blue, single-prisoner cells at six. They began their day with breakfast and church, and were working their assigned jobs—mandatory laundry and millinery work—by eight. (In the Montreal Standard, short-story writer and investigative journalist Mavis Gallant reported watching inmates do non-vocational busywork—painting walls, scrubbing and washing “already spotless” floors.) Inmates were forbidden from lying on their beds during the day and were subject to stringent rules about when and where they could speak. To incentivize behavioural adherence, many inmates received sentences of indeterminate length, leaving their fates at the superintendent’s whims. (The year the riot broke out, over 40 percent of the Mercer’s 293 inmates were serving indeterminate sentences.)

While the majority of the individuals sent to the Mercer in 1948 were convicted criminals, eighteen had been detailed under the auspices of Ontario’s Female Refuges Act (FRA), which allowed for “any female between the ages of fifteen and thirty-five years, sentenced or liable to be sentenced to imprisonment” to be held in a special facility for youth offenders for a maximum two-year term. Anyone could drag a girl or woman under the age of thirty-five before a magistrate on the basis of sworn testimony about an alleged crime. At private hearings, these girls and women were denied legal counsel and questioned extensively about their background and activities. The FRA’s low bar for evidence often meant it was used to regulate behaviours that were not, technically, illegal: being “boy crazy,” becoming pregnant outside of wedlock, associating with racial minorities and general rebellion against familial authority were all reason enough for intervention by the state. According to Joan Sangster’s book Regulating Girls and Women, which documents the period, unwed mothers, in particular, were singled out as an “emblem of delinquency.” If found guilty or in need of correction for their behaviour, the young women could be sent to a training school such as the Ontario Training School for Girls (later known as the Grandview Training School) in the city now known as Cambridge. Any individual further deemed “unmanageable or incorrigible” could then be sent on to the Mercer.

By the 1940s, Victorian notions of femininity had been renewed by the perceived sexual licentiousness and erosion of the nuclear family during the inter- and post-war eras. Driven in part by anxieties about new female freedoms, the eugenics movement gained steam in Canada, drawing respected practitioners and supporters from medicine and politics. Nellie McClung, suffragist and member of the Famous Five, openly advocated for sterilizing “young simple-minded girls,” while New Democratic Party founder Tommy Douglas’ master’s thesis, “The Problems of the Subnormal Family,” proposed that only married couples deemed “morally fit” be allowed to procreate. Between 1921 and 1939, the Mercer’s head physician was Dr. Edna Guest of Women’s College Hospital, who, in her 1922 article “Problems of Girlhood and Motherhood,” recommended sterilizing the “unfit” in order to produce “a people perfect in mind and body.” Concerns about perfecting humanity—both spiritually and physically—underpinned treatment of inmates at the Mercer.

Medical staff at the Mercer were overwhelmingly concerned with detecting sexually-transmitted illnesses—the only communicable illness listed in their annual provincial reports—and not much else. The year of the riot, medical staff performed 538 pelvic examinations and 541 blood tests, while administering only twelve vaccinations and nineteen mental-health evaluations. Guest experimented on inmates, prescribing drug doses far beyond the limits set by the Board of Health and preventing the release of inmates on the basis of their being deemed “uncured.”

Velma Demerson, an eighteen-year-old originally from St. John, NB, was sent to the Mercer for ten months in 1939 after her parents informed the police that she had become pregnant by and was living with her fiancé Harry Yip, described in the historical documents as a Chinese man. At the Mercer, while pregnant, she was experimented on without her consent; Guest administered Dagenan, a highly toxic gonorrhoea treatment not recommended for use on pregnant women. Likely as a result of this experimentation, Demerson’s son was born with severe eczema and asthma, conditions that resulted in periods of hospitalization during infancy and plagued his entire life. Like many of the other inmates at the Mercer, Demerson and her son’s lives were irreparably damaged in what was supposed to be a rehabilitative environment.

Audrey Greenfield, a maid from Hamilton, first entered the Mercer in 1940 at twenty-one to serve a maximum two-year sentence after breaching the FRA. Paroled after ten months, she promptly skipped town, remaining at large for six years, until she was caught in Hamilton in 1947 with a stolen “plaster pig money bank” containing $80.83. Greenfield returned to jail to serve out her original sentence. From Mercer medical records, we know that Greenfield was around 5'4", with light brown hair, blue eyes, and a “stout” build. The pinky finger on her left hand had previously been partially amputated.

In 1937, fifteen-year-old Lois Marjorie Osterhout breached the FRA in Kitchener and was sent to the Mercer on a two-year indeterminate sentence. For the next decade, she vacillated in and out of Ontario penal institutions for theft, vagrancy, assault, reckless driving and “keeping a bawdy house.” In 1948, Osterhout was found in possession of heroin during a nighttime raid of a private residence by plainclothes morality officers. Twenty-six years old, Osterhout started her fifth stint that year at the Mercer for a nine-month sentence. She was just over 5'1", of a “poor” build, with light brown hair and blue eyes.

Florence Chalifoux’s prison paperwork lists her hometown as Kinuso, Alberta, near Swan River First Nation, a Cree community. Chalifoux was twenty in 1937 when she was picked up in Edmonton. Her crime: failing to carry her identification papers, as had been mandated by the Indian Act. Over the next eleven years, she racked up thirty-three convictions, mainly on charges related to alcoholism, vagrancy and prostitution. She began her fourth stint at the Mercer, for assault, just three weeks before the riot. She was 5'5", with black hair, brown eyes an “OK” build, and visible scarring on her neck. When she tested positive for gonorrhoea and syphilis at the Mercer in 1948, she was immediately quarantined by staff and forced to give up the name and contact information of the person she suspected of transmitting the infections.

In the 1930s, Indigenous women made up just 4 percent of the Mercer’s population; this figure rose to 7 percent in the 1940s and 10 percent in the 1950s. Chalifoux’s incarceration was typical of the ways in which morality laws like the FRA and Liquor Control Act were increasingly used against Indigenous women in the mid-twentieth century. (This trend has continued: as of 2015, Indigenous women comprised 35 percent of incarcerated women in Canada, despite making up only 4 percent of the total national population of women.)

Greenfield, Osterhout and Chalifoux’s paths to the prisons had been remarkably similar: all came from working-class backgrounds, and all ended up serving a series of short sentences. All arrived with less than $7 in their pockets. And their first experiences of the prison would have been identical. They would have been led in silence through an austere hallway to a cloakroom. Each woman would have been given a sack-like cotton dress, apron, stockings and black shoes—these shoes identified new inmates for the first weeks of their incarceration. All new inmates were questioned extensively about their past, gave blood samples, and were given pap smears.

After being given their uniforms, Greenfield, Osterhout and Chalifoux would have had the Mercer’s exacting rules and severe repercussions laid out. The disobedient could be beaten with a leather strap (with a doctor attending), put in solitary confinement, and deprived of mail and visitation privileges. Inmates sent to windowless solitary confinement cells in the basement (“the hole”) were kept on a diet of bread and weak tea and given only a bedframe to sleep on. In a 1947 three-part report by Globe and Mail reporter Kay Sandford, Milne bragged about giving inmates three cigarettes a day, which, once the inmate was hooked, could be withheld as an incentive for good behaviour. If an inmate gave birth while incarcerated, the prospect of losing the infant to the Children’s Aid Society was held over her.

While these punishments were intended to promote good behaviour through negative reinforcement, seeing repeat offenders back at the prison cast doubt among reformers about the effectiveness of such an approach. Mercer staff were slow to respond to evolving psychiatric and sociological consensus about the effects of corporal punishment. Milne seems to have been aware of the need to remedy her institution’s reputation, claiming to Sandford in the same 1947 article that a “bit of psychology” had come to replace the “old-time beating of unruly inmates.” (Internal records reveal that, despite Milne’s assurances to the press, strappings did in fact continue.)

Despite the threat of reprisal, some inmates participated in what historians Tamara Myers and Joan Sangster have described as a “continuum of rebellious activities.” Resistance could look like insolence and petty rule-breaking or be as dramatic as assault, escape or self-injury. In perhaps one of the most explicit rejections of middle-class domestic values, inmates would occasionally form “love light” relationships with each other, much to the chagrin of officials. In institutional records, many Indigenous inmates were recorded as being “slow” or “unreachable”; these characterizations, while illustrative of institutional racism, could also reveal inmates’ quiet refusal to cooperate with authority. At the far end of Myers’s and Sangster’s continuum, one might place riots. The 1948 riot, which drew Greenfield, Osterhout and Chalifoux’s fates together, wasn’t the first or last of its kind at the Mercer—but its size, viciousness and the outcry that it drew, were unique.

The first police officers to arrive to the Mercer, hours after the riot began, were greeted by a rush of water—inmates had commandeered a firehose. Slipping on the wet floors, the officers called for tear-gas. Before it could arrive, however, police realized that the rioters were attempting to batter down a wooden door at the back of the dining hall; left with few other options, officers stormed in. According to an article from the Globe and Mail, that’s when the women “really let go.” They fashioned clubs out of smashed furniture and hurled plates and bowls at their opponents. The air was “thick with profane and obscene words”—the inmates, the article reads, delighted in giving police “the business.” Reluctant to use their billy clubs on women, officers wielded chairs in self-defence while they subdued and dragged the rioters to their cells.

But twenty of the rioters, including Greenfield, Osterhout and Chalifoux, refused to acquiesce. Using nail files, spoons and their bare hands, they removed fragments of brick from their cell walls and launched them at the guards. After several rioters kicked out the glass of their cell windows, guards confiscated their shoes. Punishment records from the Mercer reveal that the inmates who continued rioting were teargassed as late as July 4, and given ten lashes with a strap each on July 6. Though Greenfield, Osterhout and Chalifoux managed to escape being teargassed on the fourth, they were strapped on the sixth and then placed on meagre diets as punishment for their participation in the riot.

Although the riot didn’t lead to any successful escapes, and the use of solitary confinement continued, the inmates ensured that the authorities didn’t escape unscathed. Collectively, they suffered a fractured wrist, a gashed forehead, and general bites and bruising. One police officer claimed to have nearly had a finger bitten off in the melee.

More importantly, as the dust settled, the riot sparked a cascade of media coverage, which in turn prompted a backlash from institutional reformers who’d been criticizing the Mercer and other prisons for years. Much of the Toronto Star’s coverage emphasized the inmate’s mistreatment at the hands of Mercer staff, and the Globe and Mail advised provincial officials that “what makes prisoners break loose in a wild frenzy of destruction is something which needs the most careful investigation.” MPP Agnes Macphail, who’d become involved in provincial politics after a two-decade-long stint as Canada’s first elected female MP, was particularly concerned with conditions inside the Mercer. She described it as “a cold prison, a place where inmates seemed to live a life of terror, where they refused to talk even to legislature members because of an apparent atmosphere of fear.”

The riot drew attention to overcrowded, antiquated prison conditions and the use of physical punishment. To the reformers, it was simply a reminder of what they already knew about the Mercer’s failings, but it did inspire them to renew their campaign against it.

In 1964 the FRA was finally repealed, and a grand jury investigation led by a delegation of independent inspectors was launched, the results of which were published on November 5, 1964, in the Toronto Star. When provincial officials took issue with the report, Toronto Star staff writer Loretta Dempsey pointed to newspaper files on the Mercer, which were full of “riots, ex-inmate stories of ‘the hole,’ reported whippings, resistance to outside counsel for inmates,” and other troubling stories. There had also been, for years, “a dreary succession of announcements that archaic Mercer would be abandoned.”

Few survivors of the Mercer remain, and those who do have found a provincial government reluctant to make amends. Muriel Joan Walker was a promising Blackfoot ballerina who was sent to a training school by her abusive mother under the FRA at age fifteen in 1948. In 1950, she was picked up again for becoming pregnant outside of wedlock, and was transferred to the Mercer in 1951. She gave birth while incarcerated that August. Three months later, her infant son was hospitalized, suffering severe trauma to his head and arm. A letter from the Toronto General Hospital to the Mercer stated that the “injuries [did] not appear to be accidental.” According to her son Robert “Cash” Walker, he had been hurt by a matron, but his attempts to sue the Ontario government have been unsuccessful.

In 2002, Velma Demerson filed a civil lawsuit for pain and suffering experienced at the Mercer, but the Ontario Superior Court refused to hear the case, arguing that Ontario governments were immune from lawsuits stemming from incidents before 1963. While Demerson was eventually able to settle out of court and secure a private apology, no other survivors have received compensation for, or recognition of, their treatment.

Greenfield, Chalifoux and Osterhout likely never learned the effect of their rebellion. All three were released from their post-riot punishments within a couple of weeks. Greenfield again made national news that October, when she and another inmate escaped from the prison while taking out the trash. They outran a matron and caught a streetcar to the city’s west end, but were only on the lam for a few hours before police tracked them down in Hamilton. Greenfield was finally released on December 23, 1950, to the Young Women’s Christian Association on McGill Street.

Osterhout was released the year following the riot to her sister’s home on Elm Street. Chalifoux got out just a few weeks after the riot, but her freedom was short-lived; about six months later, she was given a two-month sentence for public intoxication. During the trial, she burst into a rage and had to be forcibly removed to her cell by two police officers. While being dragged from the courtroom, Chalifoux hollered a question to the court: “Am I going to spend all my life in jail?”

Although there was no way for them to know at the time, the riot that Greenfield, Osterhout and Chalifoux participated in ultimately helped facilitate the Mercer’s closure in February 1969 and its demolition later that year. Today, the superintendent’s red-brick house still stands on King Street; the rest of the grounds is now home to a stadium. But there’s a bigger reminder of the prison’s presence. Few residents of the trendy, post-industrial Liberty Village are aware that their neighbourhood draws its name from the paved road that the formerly incarcerated girls and women would walk on their way to freedom from the Mercer: Liberty Street.