Illustration by Tom Chitty.

Illustration by Tom Chitty.

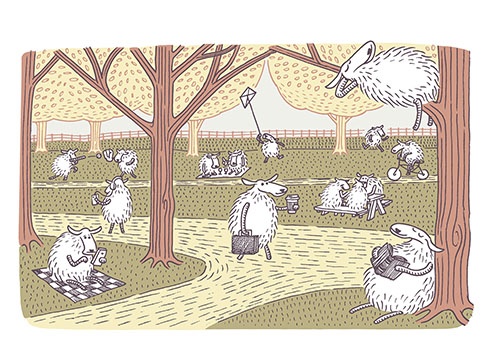

On the Lam

Letter from Montreal.

When the weather is warm, Parc du Pélican—a mid-size semi-suburban park flanked by apartment buildings in Rosemont–La Petite-Patrie—fills with locals. Young families swim in the pool; teenagers stake out the bleachers, the smell of weed carrying on the air along with their laughter. But today, a drizzly day in July, the rain is keeping park-goers away. Which is why there’s almost no one around to see me chasing down the ewe.

A hulking mass of white wool with black spots, the fugitive is one of a flock of ten. She and her pen-mates—five other ewes and four lambs—have been brought in from a farm in the Laurentians: Montreal will host them from June to August. As part of an urban agriculture project, they’ll help mow the lawns in three Rosemont parks and awaken city-dwellers to the benefits of sustainable farming. A few months prior, I’d seen an open callout for apprentice shepherds and immediately signed up, figuring I’d catch on quickly. No one told me about the sprinting.

This isn’t the escaped sheep’s first brush with trouble. She acts out so often that by the end of the summer, program organizers will have bitterly nicknamed her “Merguez.” This afternoon, her rebellion is fuelled by dissatisfaction. Like us, sheep are prone to believing that whatever is slightly out of reach must be better than what’s within their grasp. Dissatisfied with the pen’s soggy grass, Merguez hops the plastic fence and takes off running. Her lumbering dash lasts for about twenty metres before I’m able to outpace her and block her path, stretching my arms and doing my best impression of a linebacker. Merguez skids and turns to avoid me, then heads back towards the pen. When she gets there, I give her a little push, and she leaps back inside—but not before another ewe realizes how much fun she’s been missing and takes off on her own great escape.

That rainy morning, I learn that the stereo-types we’re taught about sheep don’t hold up: they may be instinctual followers, but controlling them is anything but easy.

The summer I lord over the sheep, anxiety lords over me. I’ve just ended a relationship with a man I loved deeply for teaching me that I deserved to feel safe. Eventually safety wasn’t enough, and I left. But now I’m regretful and untethered.

In September, I’ll fly across the continent with my best friend to support him after he has major surgery. For a time, he won’t be able to sit up, stand, brush his teeth or use the bathroom without help. I’ll manage his medication, make his meals, be his arms, legs and hands. I’m not ready.

On weekends, I take advantage of Montreal’s ability to make a person feel lost. The sweaty dance floor at Bar Le Ritz PDB and the smoke-filled sidewalks lining Saint-Laurent hum with enough fear and desire to distract me from my own. I stay out late, wake with the sun, then lie in bed shaking with dread until it’s time to get it together and report for my volunteer shepherding shift.

Whenever I’m with the sheep, the worry reel slows, replaced by the immediate need to keep them from accidentally bolting into the road. Eventually, many of them will likely become food, as animals raised on their farm often do—for now, though, they have no idea about their fate. For the sheep, there’s only the present moment. And for the few hours a week I spend with them, we’re grounded by the same things: the smell of the hay, the coolness of the rain, the sound of constant bleating.

By August we’ve moved the sheep to their final Rosemont location: Parc Beaubien, a large, rectangular green space two kilometres north of Pélican. Here, we don’t bother with the pen—after weeks of futile corralling, we let the animals wander free, only intervening if a ewe strays too far from the herd or too close to the road. Delighted children zigzag through the field alongside the sheep, and everyone—yuppie dog walkers, cellphone-wielding teens, bar-bound francophone men—stops to take a look. Even in Montreal, an island that sometimes feels more like a fun fair than a functioning city, the appearance of a flock of sheep invites pause.

One sunny afternoon, I spot a ewe munching on a long vine protruding through a chain-link fence from someone’s yard, playing arborist when she should be playing lawnmower. I consider shooing her, but I know she’ll be back the second I turn away. Instead, I exhale and watch her as she chews, vacant and peaceful. Today, pleasure reigns over order. And why not? There’s so little we can control in this life. Sometimes all we can do is try our best to herd each other through.