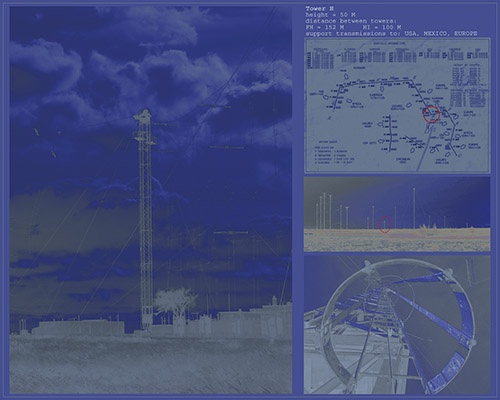

Art by Amanda Dawn Christie.

Art by Amanda Dawn Christie.

Against the Stream

Letting an algorithm pick your music is now second nature, but what gets lost in the flow?

In 2014, a decommissioned cluster of Radio-Canada transmission towers disappeared from the horizon near Sackville, New Brunswick. The towers had sent radio waves across the country and world for nearly seventy-five years, until budget cuts halted the international shortwave service in 2012.

Living one province over in Nova Scotia, I’d driven past the towers many times. I was always fascinated by their scale and their sheer physicality. They reminded me of the wires, transmitters and technicians that allowed invisible sound waves to travel—of the groundedness of listening. Of course, my own listening had been happening digitally for years, first with an iPod and more recently through music streaming. But seeing the towers come down still felt like the end of an era, a symbol for a world of music increasingly uprooted from material space.

My antidote to this new era is walking. Growing up, music from Halifax always held a special appeal for me; I loved the way it referenced familiar places, the way you could hear how artists working in close proximity were influencing each other’s sounds.

Now, strolling around Halifax as I listen to Apple Music, there are a few places I find myself returning to: the coffee shop immortalized in lyrics by some local bands, and just down the street, the second-hand store that I trekked to as a teenager to track down one of my first vinyl purchases. Nearby, there’s the dive bar that my friends and I tried to get into, underage, to see local bands.

In an increasingly groundless world of music consumption, I have access to a near-endless selection of songs and algorithmically generated recommendations. But places and people populate them—an ecosystem of musicians who exist behind the perfected interface of an app. I don’t spend much time listening to music suggested by streaming algorithms, but I’ve still noticed shifts in my habits: I’m listening to less Halifax music, less Canadian music, less do-it-yourself music, less weird music. The frictionless experience of streaming has lifted me from the very ground from which my love for music grew.

American critic Liz Pelly has written extensively on the more unsavoury consequences of streaming services, focusing on Spotify as both the most ephemeral and insidious example of their supremacy. While services like Apple Music remain tied to hardware sales like Apple’s iPhone, she writes, Spotify’s products are its playlists: some human-crafted, others developed by algorithms that suggest music based on a listener’s previous streams. Where music discovery once lay outside of a listener—often enabled through radio stations or the suggestions of a friend—these moments of newness are increasingly tied to the listener’s own habits.

The result? For one, we’re having our own biases affirmed. What’s more, we’re filling more corners of our lives with background music, absentmindedly hitting play in an act that Pelly calls “lean back listening.” In other words, Pelly writes, streaming services “have seized on an audience of distracted, perhaps overworked, or anxious listeners whose stress-filled clicks now generate anesthetized, algorithmically designed playlists.” Not even art is immune to overstimulation.

In her new book How To Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy, artist and writer Jenny Odell, based in Oakland near San Francisco, proposes a radical solution in the face of such influences. For Odell, music streaming services are just part of a seemingly endless sea of technologies now vying for our attention: from ecommerce to digital advertising to social media, our online lives feel both more expansive and less focused than ever before. We’re compelled to listen to more, scroll more, buy more—but the forces that keep us coming back to streaming services are the same ones profiting from that narrowing of our cultural gaze. Resistance to the reign of streaming, then, might begin in listening just a little bit closer. When we focus our attention on the world around us, she writes, “we might just find that everything we wanted is already here.”

Odell’s project in How To Do Nothing is difficult to pin down. Part nature writing, part cultural criticism, part political polemic, her work orbits around an ecological thinking that repositions humans not as separate from natural and cultural worlds, but instead as a fundamental part of these worlds. Taking examples from art, philosophy and her own lived experience, Odell develops a political argument for building an intentional practice of awareness and attention. The homogenizing force at the heart of Spotify’s algorithm, she argues, is not unlike the ideologies that have led to our current moment of ecological crisis and political stratification (it’s no coincidence that she began working on this book in the shadow of Donald Trump’s election in 2016). For Odell, “capitalism, colonialist thinking, loneliness and an abusive stance toward the environment all co-produce one another.”

Her solution? Put simply, she asks us to do nothing. At first, it seems like an untenable suggestion at a time when political action in the face of ongoing racial, environmental and economic injustice feels more necessary than ever. But for Odell, “doing nothing” is not a withdrawal from the world, but rather a withdrawal into ourselves. In reconnecting with our sensuous, lived experience, she believes that we might be able to reanimate our relationship to the outside world. “The ultimate goal of ‘doing nothing’ is to wrest our focus from the attention economy and replant it in the public, physical realm,” she writes.

Reading How To Do Nothing, I noticed Odell’s writing feels a lot like my own walks around Halifax with earbuds in. She fills her writing with a deep sense of place, just as quick to share notes about the Bay Area’s bird population as she is to share that she grew up in Cupertino, California, not far from tech giant Google’s headquarters. Though she writes frequently about technology, Odell’s location is significant for more than just its proximity to Silicon Valley: her commitment to locality is a strategy for navigating a digital world that can feel increasingly placeless. She sees human attention as something shifting, ecological and alive, rooted in the places that surround us. Attention, like the rose garden from which Odell writes much of the book, requires ongoing maintenance and a mindset that values recurrence.

On streaming services, each of us is an individual user reducible to a set of data. Communities, however, are not simply collections of listeners but entities that need shared interests and interdependent care. Music has always brought people together: singing in worship, borrowing a CD from a friend, meeting people at shows. Listening through systems that see us as individual sources of data and profit, we stand to lose our connections not only with music, but with each other.

Streaming services as a specific limb of the attention economy don’t escape Odell’s gaze. Writing about “Discover Weekly,” a Spotify playlist of recommendations based on a user’s recent streams, Odell describes her discomfort at being so closely identified with her data. “The weekly playlist begins to hone in, if not on an archetypal song, then an archetypal mix—we could call this ‘the Jenny mix.’”

Algorithmically generated playlists aim towards a fixed image of the human self and its habits, implicitly suggesting the possibility of a song or playlist that could perfectly capture a single user’s taste. As Pelly writes, this atomization of taste can be dangerous, lessening the likelihood of surprise or discovery. Odell illuminates the bigger implications of such thinking, reducing your tastes to something as immutable as a set of data. “To acknowledge that there’s something I didn’t know I liked is to be surprised not only by the song,” she writes, “but by myself.”

Of course, the shift to streaming has happened in parallel with drastic shifts in the economics of music, with maybe the greatest effects for musicians, who now make less income from record sales and rely more on touring to make a living. A recent Facebook post by Tamara Lindeman, frontperson of the Canadian folk-rock band The Weather Station, critiques “opaque and exploitative” streaming compensation models. Currently, listeners using a major streaming platform pay a flat monthly fee for unlimited access to millions of songs, while musicians earn a fraction of a penny per stream. Lindeman called on streaming services to change their models, suggesting one in which users pay one or two cents per stream. This change, while allowing artists to earn their fair share, could also make listeners more attentive to the music they consume.

Still, the current landscape isn’t entirely bleak. Sarah Harris, who fronts the band Property and books independent music festivals in St. John’s, says having her group’s songs queued on playlists next to larger artists allows them more exposure, if not more direct income. Mark Grundy, an independent musician based in Toronto, says he experienced a “dramatic broadening” of his taste when streaming services made available a huge catalogue of music that he otherwise might not have heard. For many—listeners and musicians alike—it seems not only impossible, but undesirable, to revert back to a world without the abundance and accessibility that streaming services provide.

Strangely, hearing more positive reflections on streaming didn’t undermine the criticisms I’d read. In fact, it sounded to me like Harris and Grundy approach their relationship to music with the sort of attention that both Lindeman and Odell seek. Streaming services are here to stay, at least for the foreseeable future. Accordingly, How To Do Nothing doesn’t ask us to turn away from these platforms. Instead, Odell’s philosophy suggests we challenge their spiral of hegemony by renewing our attention. We can seek out music that challenges the boundaries of our taste; we can choose to support local artists through ticket or merch sales; or we can take a walk through our neighbourhood.

On one recent walk, I passed the small theatre where I saw Montreal artist Amanda Dawn Christie present a multimedia project called Requiem For Radio: Pulse Decay. That performance, I remembered, was how I first heard about the fate of the Sackville Radio-Canada site in 2014.

When she learned of the complex’s impending deconstruction, Christie recorded the resonance of the towers using contact microphones, capturing a pulsing drone from each one. She used a theremin, an electronic instrument controlled by its player’s hovering hands, to trigger recordings and images of the towers; in later performances, she tuned each tower’s tone to a note on the chromatic scale and played their sounds as you might play a piano. It was alien and haunting, the sound of a place that had effectively become a ghost.

I’ve thought a lot about Requiem For Radio: Pulse Decay since then, partly just for how it sounded. But Christie’s piece is also a lament. It asks us to consider what we are losing, and what we can choose to hold on to, in an increasingly groundless world.

“Realities are, after all, inhabitable,” writes Odell. “If we can render a new reality together—with attention—perhaps we can meet each other there.” Music, I’ve learned, sounds different when I listen with greater attention. Not only does it sound better—I notice details in songs that I otherwise might’ve missed, reasons to perk up my ears—but a record starts to feel lived-in, physical, somehow a little bit closer.