Art by Guillaume Simoneau.

Art by Guillaume Simoneau.

Seeing Red

One man convinced Canadians that Russia was dangerous, and they’ve believed it ever since.

In the wake of the Soviet Union’s collapse in 1991, a woman named Svetlana sat down at her dining room table in a Toronto suburb and wrote a letter to a young Vladimir Putin. At the time, Putin, thirty-nine, was working in the office of St. Petersburg’s mayor, where he was heading the external relations committee. Svetlana, who had arrived in Canada from the Soviet Union nearly fifty years earlier, believed that put him in a position to address what she saw as a grave injustice.

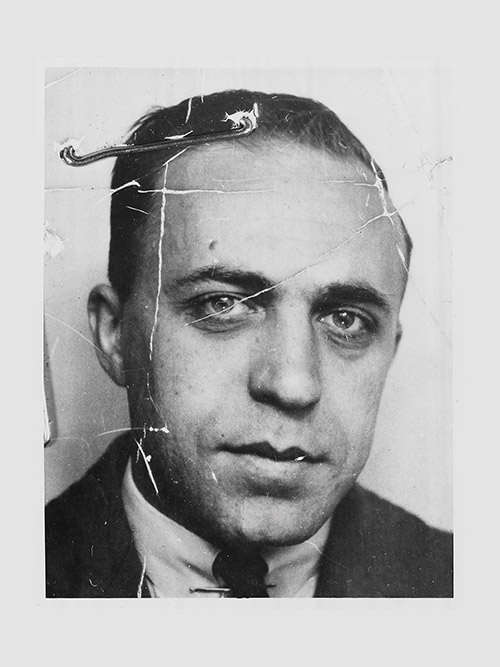

For the entire Cold War, Svetlana and her husband had been labelled by the Kremlin as vrag naroda, enemies of the people. The Soviets had good reason to feel this way: Svetlana’s husband, named Igor Gouzenko, had worked at the Soviet embassy in Ottawa before stealing classified documents and defecting, together with his wife, in 1945.

Those papers did nothing less than launch Canada into the Cold War. They revealed an active Soviet spy ring working in Canada, its supposed ally at the time, and stoked fears of a Kremlin-engineered fifth column designed to subvert and undermine democracy.

Were those fears really well-founded? It’s hard to say. Gouzenko’s defection was an opening salvo of the Cold War, but espionage between countries was hardly new. And if the Soviet syndicate he exposed had gone undetected, would it have posed a serious threat to Canada?

In fact, maybe it’s time to see Gouzenko’s bigger legacy as just that: a reminder of just how little we understand about Russia. It’s always been unclear whether Soviet threats were overblown. Today, Russia has been accused of helping elect Donald Trump and engineering the Brexit vote. Canadians have again been voicing their own worries about Russian threats, too. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has begun warning of possible Russian interference in the upcoming election, and many journalists seem to share this view, with one prominent Canadian writer, Justin Ling, claiming that Russia has the power to “bend the zeitgeist to its needs.”

This could all be true. A recent CBC investigation claimed that many trolls on Twitter—shadowy users who exist purely to heighten conflict—had links to Russia.

But the same investigation also found that a mere 0.2 percent of the 9.6 million provocative tweets referenced Canada at all, and that the trolls behind them rarely, if ever, garnered more than a handful of retweets for their nefarious work. Perhaps imagining Putin as a geopolitical puppetmaster, hand-delivering victories to the right wing of Western countries, is a fantasy that says as much about Western insecurities as it does about Russian power. If Russia has returned to its mantle of international boogeyman, feeding a collective paranoia about the source of this unstable world, the West has adopted a familiar posture too.

The Gouzenko Affair, as his revelations came to be known, was a key moment propelling Canada into this narrow and rigid view of Russia. Just one year before Gouzenko defected, the National Film Board of Canada released a movie called Our Northern Neighbour that cast Stalin’s USSR in a positive light by playing up its similarities to Canada. After Gouzenko defected and Cold War tensions hardened, Gouzenko was—depending on who you asked—the first brave hero of the Cold War or just a self-important opportunist. But ultimately, for most of Gouzenko’s life, he and his wife Svetlana were distrusted by both sides, seen by the USSR as traitors and by many Canadians as suspicious.

The couple went on to write memoirs and do countless interviews to explain their historic decision. And, when the Soviet Union fell, Svetlana believed the time had come for an official re-evaluation of her husband’s legacy—for her family to be recognized as courageous. In the letter she wrote to Putin, she made the case that the real enemy had become clear. “The ‘true end’ of the Cold War,” she wrote, “would be marked by a formal apology to all defectors who had tried to save the Russian people from tyranny.”

It is the couple’s daughter, Evelyn, who vividly remembers all this. Now seventy-three, she has outlived her parents and is carrying on their battle to have their story remembered heroically. It’s always been an unforgiving effort.

On a sweltering day in July 2017, I drove along a country road near the Niagara Escarpment, finding my way to Evelyn’s home, which is up a winding driveway, hidden from the street. Inside, it’s bright, crowded with potted plants and porcelain elephants. The walls are decorated with acrylic landscapes of autumn trees on the shores of Lake Ontario, painted long ago by her parents. Evelyn occasionally shares her place with tourists in order to help pay the bills, but today her German guests were away, giving us hours to speak about her strange life, caught in the forces of history.

By now there have been enough competing articles, books and films about Gouzenko to fill a gallery. On the night of September 5, 1945, weeks after atomic bombs were dropped on Japan and three days after the Second World War formally ended, Igor Gouzenko strode out of the Soviet embassy in Ottawa, where he’d served for two years as a cipher clerk. The embassy was trying to learn atomic secrets and he was alarmed, he later said, by the idea that Joseph Stalin might acquire nuclear weapons. He took with him a thick stack of documents and a determination never to go back.

Gouzenko’s first stop was the Ottawa Journal. He had intended to go public with his story, but when he arrived at the newspaper’s offices, he froze. “I was trembling like a leaf,” he later wrote. Just as he was about to knock on the door of the editor, "grim doubts filled my mind," he recalled, and, panicked, he turned back to the elevator.

Gouzenko rushed home to the apartment on Somerset Street he shared with Svetlana, then twenty-one. She was six months pregnant and at home with their two-year-old son Andrei. But the couple had together decided to defect and she was determined to see it through. “Go right back to the newspaper office,” she told him.

It was Svetlana, after all, who had made this moment seem inevitable the year before, when Gouzenko received orders to return to the Soviet Union for “reasons unstated.” The couple agonized over what awaited them back home—at best the dreary deprivation of post-war Russia, at worst a drawn-out death in a Siberian gulag. Then came word they had been granted a reprieve after Gouzenko’s supervisor convinced Moscow that the clerk was essential to their mission. Upon hearing this, Svetlana responded that they would “still have to face the crisis one day. What then?"

Gouzenko returned to the Journal’s office that night and spoke with Chester Frowde, the city editor on duty. In Gouzenko’s memoir he says he took out the stolen documents, spread them across the desk and “explained… that these were proof that Soviet agents in Canada were seeking data on the atomic bomb.” Nonetheless, “I could see from the man’s expression that he thought I was crazy.”

Gouzenko recalled Frowde saying “this is out of our field,” suggesting he talk to the RCMP before sending him away. In an interview with the journalist John Sawatsky years later, for a book about Gouzenko, Frowde claimed the man’s bizarre manner made him impossible to understand, much less believe, though he regretted not spending more time with him.

He spouted, “It’s war. It’s war. It’s Russia,” Frowde recalled. “Well, that didn’t ring a bell with me because we were not at war with Russia—World War Two was over—and I didn’t get the connection. I plied him with questions… and he just stood there, apparently paralysed with fright, and refused to answer.” Gouzenko returned home for a restless night, with Svetlana reassuring him they would have better luck at the Ministry of Justice in the morning.

They didn’t. The justice minister (and future prime minister) Louis St. Laurent refused to take a meeting with the couple. And so they tried their luck at the Ottawa Journal again. This time Gouzenko spoke with reporter Elizabeth Fraser, and Svetlana’s reassurance got him talking. But he still couldn’t quite communicate the gravity of what he wanted to say. “His story was unbelievable at the time,” Fraser told Sawatsky. “I became convinced he was paranoid and had not only delusions of persecution but of grandeur.” Fraser suggested the couple go to authorities to try to get naturalization papers.

“This man and his very pregnant wife came in,” recalled Fernande Coulson, a secretary at the Crown Attorney’s office. “He said… ‘I have papers inside this jacket to show.’” But it was only when Coulson noticed Svetlana’s black purse, bulging with papers, that she began to believe they were serious. Coulson frantically called everyone who might help, eventually even calling Prime Minister Mackenzie King’s private office. “Somebody has got to protect these people or else they will be killed by the Russians,” she pleaded.

After scheduling a next-day meeting with the RCMP’s deputy chief of intelligence, Coulson convinced them they were in good hands, though inwardly, she recalled, “As I watched him [leave] I said to myself, ‘That man may not be alive tomorrow.’”

She wasn’t alone. Suspecting that Soviets were by now crawling the quiet Ottawa streets looking for him, Gouzenko anticipated being caught at any moment. At home, “Every noise was bothering me,” he later wrote. “After a short time, I got up and walked to one of the front windows. As I looked down, my heart skipped a beat! Two men were seated on a bench in the park directly opposite, and both were looking up at my window!” Gouzenko told a neighbouring couple that his life was in danger, and they set up their pull-out couch to let the Gouzenkos stay the night.

Around midnight, four Russian agents, at least one carrying a revolver, approached the apartment building. Another neighbour described them as having “a Russian-movie sleaze look,” as they peered through the ground floor windows looking for Gouzenko.

What these Russians didn’t know was that Coulson’s earlier frantic calls had caused a stir; the two men on the bench across the street were in fact RCMP officers sent to make sure Gouzenko wouldn’t commit suicide. They watched as tensions appeared to come to a head: the Russians entered the building, followed by two Ottawa policemen who had been alerted to the situation. The two Ottawa officers found Gouzenko’s door smashed open.

“I walked in with the gun in my hand and had the whole four of them in the parlour,” said one of them, Constable McCulloch. The Russian agents explained who they were and said Gouzenko had some papers they needed, and embassy staff had the right to enter, but they had mislaid the key. After the confrontation, though, they quickly left.

If just one of the Russians had knocked on the neighbours’ door they might have caught Gouzenko that night. He had watched the whole scene from the keyhole across the hall.

The morning after their close call, the Ministry of Justice was interested in hearing what Gouzenko had to say. By then, virtually everyone in the Canadian government had heard rumours of a Russian defector; the question was what to do.

With Soviet agents fanning across the city, two RCMP officers spirited the Gouzenkos to a cabin in Smiths Falls, Ontario. The officers in charge told Sawatsky that Gouzenko’s nerves were fraying. He would dive under tables when startled. Around midnight, an unfamiliar man went into the next-door cabin with a typewriter. Soon, “here was Gouzenko standing outside of the cabin completely naked, both arms raised over his head, hollering ‘Help! Help!’” recalled one officer, John Batza. The man with a typewriter turned out to be a schoolteacher looking for solitude as he worked on a thesis. Nonetheless, they left two days later in search of somewhere Gouzenko could relax.

The family was moved to “Camp X,” a decommissioned base on the northwestern shore of Lake Ontario. A lone fifty-year-old farmhouse was flanked by fields full of cows; it had been set up a few years earlier as a training ground for British and American spies to learn sabotage, lock-picking and code-breaking. For the next two years this would be the Gouzenkos’ home, along with a handful of RCMP officers stationed there with them.

George Mackay, one of those RCMP guards, described Gouzenko as “thoroughly frightened.” But he didn’t just fear that Soviet agents might show up and put a bullet through his head. He felt a deep guilt, knowing the repercussions his family members likely faced in Russia. He was right: Svetlana’s parents and sister would all be imprisoned for five years. Her niece, Tatiana, would be taken from her mother and sent to a grim orphanage. Gouzenko’s mother would be interrogated until her death inside Moscow’s notorious Lubyanka prison.

Gouzenko was clearly still suffering from traumatic stress, a worry for Ottawa. When the RCMP interviewed Gouzenko about the documents he stole, his distracted state made the interrogations long and difficult. Then a new security concern emerged: Svetlana’s pregnancy.

No one else in Canada has had a birth like Evelyn’s. Gouzenko figured that Soviets may be patrolling hospitals to catch them, so to minimize the risks, or at least quell his worries, the RCMP agents cooked up a careful scheme. At dawn on December 8, 1945, Mackay posed as a taxi driver and drove Svetlana to an Oshawa hospital while another agent posed as her husband. To get around administrative questions, the agent explained in broken English that he was a Polish farmer and flashed a wad of cash “that would choke a horse” to make clear who was going to pay for the delivery.

Gouzenko and Svetlana wanted to name the new baby Avi, but as the family would soon be given cover names and encouraged to blend in, they were told the name Avi was too Russian. So they chose Evelyn, thinking they could always call her Evy.

Back at the farmhouse, Svetlana filled the rooms with papier-mâché Christmas ornaments, and Gouzenko began to find a kind of peace painting the lakeshore. But Gouzenko still had bouts of paranoia, at one point hushing Svetlana so they could press their ears to the wall. They heard paper rustling in Mackay’s room. “What are they preparing in there?” Gouzenko nervously asked her. On Christmas Day they learned the answer. The agents had been wrapping presents for them.

As Gouzenko settled in, the importance of his revelations became clearer to the agents interviewing him. The documents he stole from the embassy revealed a far-reaching, though generally ineffective, Soviet espionage network in Canada. They showed that Fred Rose, a Member of Parliament with the Labour-Progressive Party (formerly the Communist Party of Canada), was working with Russian agents, and that the Soviets’ key source for atomic espionage in Canada was Alan Nunn May, a British physicist who was later arrested.

But to Ottawa, the most important revelation was that there was a Soviet spy ring in Canada at all. Sensing a unique opportunity to strengthen Canada’s hand in the post-war era, Prime Minister Mackenzie King travelled to Washington to warn President Truman that the Soviets not only had spies in Canada, but also in the United States.

But this was mere months after the United States had dropped a nuclear bomb on Japan, and geopolitics were shifting. The Soviet Union had thought it would exit the war as a global power on equal footing with the United States, but after the bomb, foreign-policy hawks in both countries pushed a binary choice for the USSR: either accept its position as a secondary power or enter an arms race. A third, briefly pursued option was to use international control of the atomic bomb as a starting point for cooperation.

Truman feared that exposing the Soviet spy ring prematurely would jeopardize such an international nuclear agreement, and Mackenzie King was similarly reluctant to start a confrontation, says historian Amy Knight. Enter then-FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, who couldn’t accept the leaders’ reticence; he believed Truman was soft on communists, and he wanted to turn the power of his agency on leftists across the United States. Hoover had been briefed on Gouzenko’s defection from the earliest days, and the Gouzenko Affair appeared to him as the perfect opportunity to expose the supposed communist threat. After reading an internal FBI memo about Gouzenko in December 1945, Hoover scrawled across the bottom of the page, “Same spineless policy as pursued here.”

But Hoover knew how to manipulate. He had a long history of cultivating journalists, including Drew Pearson, an NBC radio reporter. By February 1946, Hoover had apparently had enough, because that month Pearson announced to his NBC audience that a Soviet spy had revealed “a series of agents planted inside the American and Canadian governments,” a “gigantic Russian espionage network.”

Mackenzie King’s hand had been forced. Nonetheless, when he publicly acknowledged Gouzenko’s revelations on February 15, 1946, the West’s fragile relationship with the Soviet Union immediately collapsed; the multilateral talks to control the bomb were upended in favour of an aggressive Western military supremacy.

In Canada, an investigative committee was formed and Mackenzie King used draconian powers granted to him under the War Measures Act—believed until then to be expired with the end of the war—to detain people named in Gouzenko’s documents, stripping them of their right to a lawyer. Ultimately, about three dozen people were tried and nearly half of them convicted.

These so-called spy trials were front-page news, and Mackenzie King now saw himself as a key figure in the righteous fight against communism, writing in his diary that “it can honestly be [said] that few more courageous acts have ever been performed by leaders of the government than my own in the Russian intrigue against the Christian world and the manner in which I have fearlessly taken up and have begun to expose the whole of it.”

His self-satisfaction was intimately tied to his anti-semitic belief in a Jewish-Russian conspiracy—a frequent theme during the Red Scare. In another entry, Mackenzie King wrote of “the Russian method to control the continent.”

By March 1946, King’s public claims had shifted Canadians’ perception of Gouzenko’s revelations. He told the House of Commons that Gouzenko had risked his life in service of Canada and said that the country “was being made a base to secure information on matters of… grave concern to the United States.” Gouzenko found himself assigned the role of the man who warned the West.

The Canadian government acted fast. The investigative committee launched by King concluded that “there exists in Canada a fifth-column organised and directed by Russian agents.” By 1950, the Canadian government had secretly launched harsh measures meant to spot these potential communists that Moscow was supposedly cultivating. It listed approximately sixteen thousand suspected communists and another fifty thousand sympathizers to be watched by the RCMP or detained if necessary. The program only ended in 1983.

Anti-communist messaging flooded newspapers. “Everywhere are evidences of the continuous underground, cancerous movements of Communism,” read one typical ad by Canadair. “Only eternal vigilance can protect us against Communism and its infiltration into our way of life.” Gouzenko had known that his actions might alter history, but it’s impossible to say whether he had expected such an utter souring of opinion against his home country.

In her dining room, Evelyn filled my teacup and began describing her latest frustration in the long, unending battle to see history written the way Gouzenko wanted it, the way Svetlana told it. She showed me a book about Soviet intelligence she had recently read, a historical work called Near and Distant Neighbours—a useful volume, she said, if written by someone “utterly naïve,” at least in his casual attitude about Russia’s efforts to build a fifth column.

Evelyn carries her fight to wherever it must be waged. To celebrate Canada’s 150th anniversary, the Canadian Museum of History showcased defining moments that had shaped the country, and Evelyn used this occasion to lobby the museum to change the description of her father on its website.

One sentence of the paragraph-long writeup said that Gouzenko, upon learning he would be sent home, “stole a number of documents and defected. His evidence of a Soviet spy ring in Canada during the Second World War was shocking to a country that had been sympathetic to its wartime Russian ally.” One word here bothered Evelyn, and she wouldn’t let it slide unchallenged. She wrote to the museum’s president and proposed an alternative that emphasized the Soviet threat while omitting “defect” or “defector.”

“When you look it up, defectors are put in the same category as traitors,” she told me, “and you can’t be a traitor to tyranny; it’s impossible.” She paused. “That was my dad’s phrase.”

In the family’s first years at Camp X, Canadians were clamouring to know more about the mysterious man who revealed the spy ring, so Gouzenko spent much of his time writing a memoir, first as a series of magazine articles, then as a book called This Was My Choice, published in 1948. In his writing he described his motivation for defecting as purely ideological. He feared Joseph Stalin getting his hands on the atomic bomb and worried another war was on the horizon. He wrote glowingly of democracy and warned that “there is no use treating these Communists merely as members of another political party. They live and lurk in the shelter of your hospitality as enemies of everything you hold sacred.”

He seemed happy to play the role assigned, writing that on the night he left the embassy, “during the long walk from Somerset Street to Range Road, I came as close to becoming a hero as I ever will.” And over time, he polished his story. His writing quickly served as the basis for a Hollywood movie called The Iron Curtain. He frequently appeared on television for interviews with a cloth bag over his head, eye holes cut out. For a man who first seemed so intensely afraid of being caught, he was revelling in his new life as a media darling.

While Gouzenko’s public image grew rosier, his defection was triggering not just a Red Scare at home, but a widening rift in the international order. The West and the Soviet Union had two brewing battles, says Knight, the historian. “One was that Stalin and the Kremlin wanted to exert as much possible control over countries in Eastern Europe,” she says. The other was the atomic bomb. The overriding need to win the war had meant that the West had turned a blind eye to Stalin’s monstrous regime and was only now taking stock of it.

That still doesn’t mean the spy ring was a dire threat. If left unchecked, perhaps it would have grown into the Soviet’s fifth column, but as it failed to collect actionable intelligence, the problem was more about “malign intent,” says Knight.

It’s clear now that that intent, trying to interfere in democracies, has been a trademark of the Russian state over the years. Knowing that, says Knight, “we could wind the clock back… and say that maybe if people had been more realistic about the nature of the Soviet government and who Stalin was, maybe we wouldn’t have been so surprised that they were trying to steal our atomic secrets.”

As for Gouzenko himself, “it could be that his motives were mixed,” says Knight. He was only twenty-six, with his life ahead of him and a family to support. If he was even partially motivated by finding a permanent home in Canada, exaggerating the gravity of the spy ring couldn’t hurt.

“Once he actually had defected and the reality hit, he’s living under an assumed name, he’s scared to death that he’s going to be killed by the Soviets.” Given those circumstances, “it shouldn’t actually surprise us that… he started trying to prove how important he was, and he got very grandiose and narcissistic,” she says.

Once things were set in motion, it seemed beyond any individual’s control how the scandal grew, changed and ultimately crystallized.

After two years, the family had outgrown the cramped farmhouse. They were settled on the outskirts of Toronto, where Gouzenko and Svetlana struggled to adjust. They spent the rest of their lives posing as Czech immigrants, living under a cover name given to them by the Canadian government—a name that, oddly, is a Czech word for “traitor.” Evelyn asked that the name not be published to preserve the privacy of her extended family. Though she can’t say for sure how the family got the name, she fears it was no coincidence, showing that there was always some distrust lurking under the initial hero worship.“We were labelled from the get-go,” she told me.

In their new neighbourhood, Gouzenko and Svetlana tried their best to cloak their Russianness from their own children. Still, the kids in Evelyn’s school would whisper and taunt. Did the children know anything other than that her parents spoke with a Russian accent in the era of the Red Scare? Evelyn isn’t sure. She grew up knowing some people were hostile towards her family for reasons she couldn’t fathom.

She remembers, in grade three, being strapped by the teacher for being late in a way that felt “beyond anything logical,” discriminatory. The next time she was late, she simply didn’t go to class. Police were called, and Gouzenko and Svetlana feared Evelyn had been abducted. Later, they sat her and her siblings down and asked them to be more cautious. They were confused. “All of our friends weren’t careful,” Evelyn says.

Evelyn was twelve the day she heard a loud bang outside of her home. She rushed out with her camera and saw the family’s mangled mailbox lying at the foot of the driveway. The mailbox was blown out and its metal flap had a single hole in it, the inside covered with black soot. She snapped a photo and raced to tell her parents, but found their answer unsatisfying: “Just some pranksters shooting mailboxes.” Impossible, she insisted. The way the hole blossomed outwards made it clear that something had exploded inside the mailbox.

“I had to find out the truth. I had to find out what happened,” says Evelyn. So that night she crept down the hall and tried to listen in on her parents’ hushed, panicked conversation. But she couldn’t understand what they were saying. “They would talk to each other in their own language, which we were not permitted to know,” she says. Until then she never questioned why her parents spoke an entirely different, private language.

Rumours continued to swirl at school that they were Soviet spies, and at sixteen, after being bullied yet again, Evelyn went home to confront her mother in the kitchen. With a sigh, Svetlana explained that neither she nor her husband were Czechoslovakian immigrants, that Evelyn’s father was the famous Igor Gouzenko. She must never tell anyone, her mother said.

Evelyn felt the truth rapidly pulling into focus as she reflected on the strangeness that seemed to follow her family around. Reeling from the news, all she wanted was to “not be from an immigrant family,” she says. “It’s a horrible thing to feel. I mean, my parents were beautiful.”

It took her a long time to come to those terms. A few months later, she met a man named Brian, six years her senior, who had just returned from the air force. She became pregnant, and “everything just collapsed,” she says. “That wasn’t an acceptable thing for girls to do.” She moved in with Brian in Toronto and left her father in the dark. Svetlana wouldn’t tell her husband, either, not wanting to hurt him.

Weeks after she turned seventeen, Evelyn married Brian in Buffalo, New York, and gave birth to a boy later that year. Eventually Gouzenko found out about both the marriage and the pregnancy. But the messy truth did not, after all, crumble him and the life he had built in Canada. He “embraced it,” Evelyn says.

Evelyn had glimpsed an escape from her extraordinary reality. Brian was her passport to Anglo-Canadian, middle-class life, even as he would laugh at her parents’ accents. “It was hard to take,” she says. After nearly a decade and two children, Brian abandoned the family, remarrying several times. For Evelyn it was her last marriage. She focused on her kids and her career as a meteorologist, eventually working for Environment Canada, investigating acid rain and atmospheric pollutants. She then left Ontario and her parents behind, and it would be seven years before she returned home and rekindled her relationship with them.

Igor Gouzenko was once asked on CBC’s This Hour Has Seven Days about his experience as a spy. He snapped back, “Don’t use such horrible words. Don’t forget, I exposed [the] Soviet spy ring.” The truth is, though, he had played a central role in the very same spy ring he revealed.

This sort of exchange was typical for Gouzenko, sensitive as he was about his place in history. “Gouzenko always had a theory that before the Russians would kill him, they had to destroy his credibility,” his lawyer, Nelles Starr, explained to Sawatsky years later.

In 1964, Gouzenko sued both Newsweek and Maclean’s. Newsweek’s sin was calling him a defector and implying that defectors suffered from psychological trouble. Gouzenko refused to settle after the magazine’s offer of $1,000 in damages. The case proceeded and he ended up with nothing. After all, he had defected.

Maclean’s, on the other hand, portrayed Gouzenko as ungrateful to Canada, terrible with money and having delusions of great wealth. It implied his life wasn’t in danger anymore. This case went to court, and this time the court ruled in Gouzenko's favour. The court agreed he had been libeled and he was awarded the grand sum of one dollar in damages.

The last lawsuit Gouzenko launched was against John Sawatsky. In 1980, Sawatsky published the book Men in the Shadows, which included a chapter on Gouzenko that portrayed him as an opportunist rather than a courageous ideologue. Sawatsky considered Gouzenko, with his multiple libel suits, “a legal bounty hunter.” Sawatsky told me “there’s just no way I was going to concede anything to him. I had to mount a defence and so I did a lot of research.”

As part of this defence, Sawatsky interviewed nearly 150 people who knew Gouzenko, from RCMP officers to neighbours to journalists and even Svetlana. These interviews would later be compiled in the book Gouzenko: The Untold Story. Sawatsky maintains the book “is where the true picture of Gouzenko really came out and just how much he craved publicity. I mean, he absolutely needed it.”

In 1982, Gouzenko came down with a terrible flu. He had gone blind from diabetes in the preceding years and, one night, stood in his home listening to the radio, the pastime that had replaced painting. As he conducted an imagined orchestra, seeming at peace, he collapsed onto a nearby table; Svetlana couldn’t resuscitate him. Gouzenko died on June 25, 1982, thirty-nine years to the day after his arrival in Canada. He’d always feared he would die by a Soviet bullet, a martyr’s death. Instead he lay killed by a burst blood vessel.

When Gouzenko died, his libel suits died with him. For Sawatsky this meant that all of the interviews he had conducted could finally be published. And because Evelyn was unmarried, working full time and able to support her mother, she committed herself to doing so. That also meant spending the last nineteen years of Svetlana’s life coming to terms with the couple’s legacy and how to defend it.

“I understood how much difficulty there was in her life,” Evelyn told me. “I didn’t understand the full scope of it, but I certainly found out later, through all those years with her.” That’s something few people have, “that opportunity to get to know our parents,” she says. “I got to know at least one parent really well.”

Any challenges to Gouzenko’s narrative poked at his insecurities about his place in history. And as the inheritor of the family’s history, Evelyn finds those critiques sit heavily on her shoulders, too. Today, it often feels like history is repeating itself. Last year, Christopher Wylie exposed the illicit data-gathering of the political consulting group Cambridge Analytica, which “harvested”millions of Facebook users’ personal information to conduct “psychological warfare” on behalf of the Trump and Brexit campaigns—information that was then allegedly shared with Russian intelligence. Though it’s too early to gauge the lasting impact of those revelations, the parallels are striking. Wylie played a significant role in the nefarious effort, and by exposing it, has both contributed to a greater understanding of an important issue and helped fuel fears about it.

“If Winston Churchill said that Russia is a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma, then Canada’s approach to Russia today is one of hysteria wrapped in a frenzy inside a more general incoherence,” wrote University of Toronto political scientist Irvin Studin in an op-ed last year. This is not to say genuine threats shouldn’t be taken seriously, but Canada also has a pattern of exaggerating its fears to a point that could weaken our understanding of important issues. Gouzenko’s revelations led to a database of thousands of leftists the Canadian government was prepared to imprison at a moment’s notice; what sort of policies might we turn to now if Russia were caught putting its thumb on the scale in a Canadian election?

I visited the Mississauga cemetery where the Gouzenkos are buried, side by side—one of the only places where their story is told as they wanted. Their tombstone was unmarked until Svetlana died in 2001. After, it read, “On September 5th, 1945 in Ottawa, Canada, Igor, Svetlana and their young son Andrei escaped from the Soviet Embassy and tyranny.” Escaped, not defected.

The two may have been driven by their belief in the moral supremacy of democracy, or perhaps a taste for the comforts of well-stocked grocery stores. Gouzenko may have believed his destiny reached beyond that of a low-level cipher clerk, or maybe he feared he’d be dragged back to the Soviet Union to waste away in a work camp. For Evelyn, though, their motives are still succinct enough to fit on a book jacket or movie poster: “They wanted to warn the West.”

History continues to repeat itself, but in new, strange configurations. Just as Svetlana wrote to Putin to have the family’s name cleared, Evelyn has written to President Donald Trump for help, thinking he could get in touch with Putin on her behalf. In that letter she echoed her mother, saying that to mark the true end of the Cold War, all Soviet defectors would have to be exonerated in the eyes of the Russian people. She doubts Trump would do this favour, but still, a new era brings new hope.