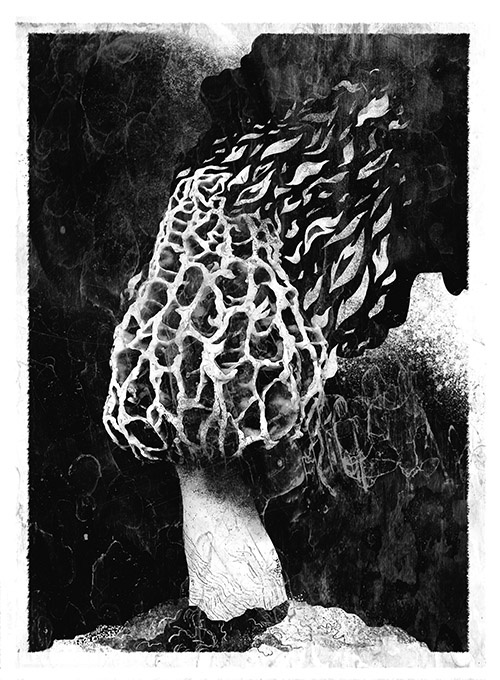

Illustration by Dushan Milic.

Illustration by Dushan Milic.

In the Burn

In wildfire-ravaged BC, Rachel Jansen learns to keep up with the relentless rules of mushroom-hunting.

We pull into the town of Clinton, British Columbia just after 7 PM, the summer sun still slung over the tops of the surrounding mountains. My friend Marte, her cousin Jonas and I wait quietly at a café called Cordial, our hands wrapped around mugs of coffee, having exhausted the need for conversation in the five-hour drive up from Vancouver.

A doorbell jingles and Ali walks in. At nearly six feet, lithe and with freshly washed blonde hair, I doubted anyone in the café would have guessed Ali’s been living in the bush twenty kilometres north of here for nearly four weeks now. But maybe I’m only projecting my own internalized fears; also a woman, also blond and slight, I am forever trying to throw off the typecast I presume people have for me.

Ali slides into the seat next to mine. She’s been away for a couple of days, visiting her sister in Pemberton. “I needed a break,” she says, taking a sip of my coffee. “But I’m excited to go back.”

This is Ali’s fourth season picking morels, an elusive culinary mushroom that grows with fecundity in previously fire-razed forests, or “burns,” as they are colloquially known. Friends from university, Ali indoctrinated Marte into picking two years ago, and Marte in turn inspired me with her stories of days spent picking mushrooms in fields of wildflowers. Having recently graduated from my master’s and feeling claustrophobic in the city, I was looking forward to the possibility of making quick cash outdoors without a superior breathing down my neck. In the past, I’d mostly worked in retail or academia and I was excited to be my own boss.

We follow Ali into the parking lot, where she slips into her dust-coated car and we into ours. Within a couple blocks we clear the town, continuing north on the highway until Ali indicates left onto Chasm Road.

Almost immediately, the burn appears. Between swaths of greenery are pockets of red-needled conifers, their trunks licked black and splitting. Further still, whole copses stand like bristles of a brush in the sooty earth, grass growing incongruously at their ashen base. Our cars climb up to the top of a valley and the view widens; about a third of the hills in front of us are bald, like a head of hair that caught flame. A third shine orange and red with discolouration from drought, and a third remain pristine, a strange museum-like exhibit of what a forest ordinarily looks like.

The Elephant Hill fire, which raged through this area in July 2017, was among the largest of the 160 fires that sparked in British Columbia that month, prompting a provincial state of emergency. Stretching over 192,000 hectares in BC’s interior, the Elephant Hill fire alone decimated over one hundred homes in the seventy-six days it burned.

As we wind our way down into the valley, I spy several campsites—clusters of weather-worn tents covered in tarps that snap in the wind. At the bottom of the valley, a coppery river moves in fits and spurts over the boulders wedged within it. We pass a gravel pit that sports a large white tent and a cardboard sign that says “buyer.” Then we begin ascending the opposite side of the valley until, at Kilometre 26, Ali’s car slows and veers down a road so narrow we certainly would have missed it without her.

The road is long and laced with rocks that jostle us every few metres. My car tips sideways on a slab and I’m about to question how much farther I can go when I spot a gazebo-looking structure sitting in a flat, treeless space. Ali steers her car over and we follow suit. “Home sweet home,” she says as we slam our car doors shut.

Our camp is in one of the “pristine” areas of the forest—the normal, unburned part. Evening sun honeys it. A tarp covers a kitchen area, complete with a table, two-top stove burner and crates of dried goods, carrying everything from oatmeal to packages of fuzzy peaches. A bonfire pit has been constructed, with fallen logs pulled around for seating. Several tents peek out from the circle of surrounding trees like curious animals. On the opposite side of the road I’m relieved to see a porta-potty and two huge garbage bins.

I’m surprised to learn that the other girls we’re camping with, friends of Ali’s, are still out picking. It’s nearly 9 PM and mosquitoes hum around us with such intensity I tug the strings of my hoodie so only my nose and eyes show.

We’ve already prepared dinner by the time another car parks next to mine. Jenna and Sophie emerge slowly, moving like elderly women instead of spry twentysomethings. Their hands and faces are so dirty with ash, I realize Jenna has freckles only after they’ve gone to the river to wash off. They gratefully accept bowls of curry and stare into the fire as they chew. I eagerly ask them several questions about picking but stop once their answers become monosyllabic; they’re clearly exhausted and I can only imagine how tiring my enthusiasm must be.

It isn’t until the sky is fully leached of light that a fourth car appears. The German Boys, as the girls refer to them—a pair of childhood friends from Germany who the girls met their first week picking and decided to share a site with.

Felix comes to the fire first. His hair is shaved close to the sides of his head, he walks on the balls of his feet and this is his sixth season picking. After introductions are made, he turns to Jenna and Sophie. “So,” he asks. “How was your day? How much did you pick?”

“Sixty,” Sophie says, meaning pounds.

“Together or each?”

“Each.”

An emotion I can’t yet parse flickers across Felix’s face before he recovers it. “That’s the most you guys have picked, yeah?”

“No,” Jenna says, a touch defensively. She brightens. “How was your day?”

Felix runs a blackened hand over his face. “Oh, Andre and I had a not-so-good day today.”

As if on cue, Andre, broader and more reserved, hauls what looks like a witch’s cauldron to the fire—he’s going to heat the water, I am told, for a shower, using a bucket perched on their car with a vinyl tube dangling down. One by one, people move to their tents.

At seven the following morning, when the buzzing of my phone alarm wakes me, I pry my eyes open and realize the German Boys’ car is already gone. And though the girls’ car is still there, I can see that they’re packing it up. Quickly, I shimmy out of my pajamas and into nylon pants, throwing on the same hoodie from last night. Evidently, the workday has already begun. I don’t want to be left behind.

For many, the fires raging across the west coast have meant displacement and grief, signalling further ecological devastation to come. But for some, major forest fires bring opportunity. Where there is fire, there are morels, a coveted mushroom species sold in gourmet stores and restaurants. Before I went picking I’d yet to try one, but once I did, I understood the hype—meaty and flavorful, morels don’t need much else to make a delicious meal. Their rarity, some say, adds to their flavour.

During May and June, morel-pickers arrive to these burns in droves, eager to make fast cash. Our burn is home to twenty-five campsites, though there are over three hundred pickers, many of whom have chosen to camp off-site. Some two to three thousand people forage morels commercially across BC every year.

Historically, pickers have been self-identified outcasts, people on the margins of society who want to spend eight weeks tramping alone through a desolate landscape. Drugs and alcohol have often been cited as problems on the burns. Recently, the demographic has shifted and there are more people like me, students looking to make money in the summer.

There’s no mystery to the increase in fire ignitions in recent years. “As the atmosphere heats up, it’s causing the summers to become drier for longer periods,” says John L. Innes, a professor of forestry at the University of British Columbia. “And as the land dries out it becomes easier for fires to start and spread.” A recent report by Environment and Climate Change Canada found that BC had warmed by 1.9 degrees in the past fifty years, almost double the global average.

Until recently, fringe resource economies like morel-picking have mostly flown under the radar. But as fires encroach closer to areas with human development, so too do thousands of mushroom pickers, throwing a spotlight on the industry and its inherent issues.

That first morning, the girls’ heads are bent together and as I approach they seem to lower their voices. They needn’t worry; I wouldn’t be able to decipher where it is they are talking about, even if I wanted to. They speak as if in code, murmuring about “the money patch,” “the place by the river,” “that first swamp.”

Unlike other types of mushrooms that grow in the same place each year, morels are unpredictable, and locating them can be gruelling work. As a result, pickers become territorial and secretive about the patches they find. There’s an unwritten rule on the burn not to park too close to another car when you’re out picking, and I once heard about a man who carried a rifle to intimidate other pickers. But gently hostile behavior—people whispering about their spots, or giving each other the hairy eyeball for stumbling onto the same patch—is much more typical.

Right then, new to picking and unaware of the ethos, I ask Ali where she thinks would be best for us to go. She kindly hands me a map that’s creased like a hand and points to a thin, unnamed line. I thank her and pocket the map.

Marte and Jonas and I drill holes into the Home Depot buckets we brought, which we will use to collect the mushrooms. The holes are necessary; morels require ventilation to stay fresh. The buckets are used to fill the crates, which carry about ten pounds of mushrooms each. Optimistically, we pack two crates each into the car.

None of us have said so aloud, but I think we’re all a bit intimidated by the forest, the sheer magnitude of it. I strap my bear spray to my belt loop and place my GPS in my pocket, hoping I never have to rely on either. I also stuff three EpiPens into a fanny pack; I’m allergic to bees and anaphylactic shock is a possibility.

We pile into the car and bump down our road. The clouds look flat-ironed to the sky and a hawk circles in front of us, casting looping shadows. We drive fast with the windows down to whip all the mosquitoes out of the car, while bickering over which road we think Ali was indicating. When Marte realizes she’s forgotten her bear spray, relief runs electrically through me. “We’ll stick together then,” I say. Neither Marte nor Jonas disputes the idea.

The forest, mostly made up of charred pine, is strewn with fallen trees whose roots were weakened by the fire. The ground alternates from a shag rug of colourful pine needles to mounds of dirt and ash—dried-out root systems that your leg falls through. The air is damp and cool, cleaner than I expected. I slap my shoulder and every inch of my hand comes back winged with dead mosquitoes. Perfect mushroom conditions, Marte assures us.

The relationship between mycelium, the underground network of filaments from which mushrooms fruit, and tree roots is still somewhat mysterious, and the relationship between morel mycelium and fires even more so. Many theories have been postulated as to why morels grow in such great quantities in burns—lack of competition, a sudden influx of minerals from decaying plants, changes in soil pH—but so far no studies have been conclusive. In 2017, research from China suggested that it was moving from nutrient-rich to nutrient-poor soil that triggers the filaments to fruit, but attempts to recreate this process proved costly and laborious. So restaurants rely mostly on foragers to supply them with mushrooms and are willing to pay the price; a fresh pound of morels can go for as much as $25.

I scurry after Marte through the forest, ducking under burnt logs as I go. I don’t know why, but I imagined there would be some sort of road, some path through the trees. I suppose it’s easy to forget there are places in nature that haven’t yet adapted to us humans. I jump from a log onto the ground and nearly smack into Marte, who is bent over, looking at a pinecone between her feet. It isn’t until she takes out her knife that I understand; the pinecone isn’t a pinecone but a morel.

Marte cuts the cap off and holds it up for Jonas and I to inspect. Wrinkled and brown, with a lattice of protruding gills, the morel is shaped like a pear, a little bigger than the size of a thumb. Marte drops the mushroom into her bucket and I scan around where I’m standing. A little ways off I see a cluster and run over, unsheathing my knife and crouching down. The mushroom is moist to the touch and breaks slightly at my fingertips. I slide the knife through the white stem, releasing the dark cap into my hands. I press on it, flip it upside down. “It’s hollow,” I say with surprise.

Marte laughs, her voice trailing until I realize how far she away she is. I scramble to keep up.

We carry on like this for an hour or so: me following Marte, Jonas following me, all stopping every few metres to pick mushrooms we see in our path.

Back at the car, I peer into Jonas’ bucket and gasp. “Am I really leaving that many behind?”

Jonas smiles and lights a hand-rolled cigarette.

While it’s possible to sell mushrooms directly to restaurants and make the full $25 a pound, doing so requires daily trips to Vancouver, because morels lose their moisture, and valuable weight, by the hour. For this reason, most pickers end their day by selling to buyers, many of whom work for larger distribution companies, even though the price per pound is significantly reduced.

Elephant Hill has an estimated 250,000 pounds’ worth of harvestable morels. About 70 to 80 percent of those mushrooms are sold to European markets, primarily Germany, Italy, Switzerland and France. Because of its size, Elephant Hill has attracted more than ten buying stations, which, by the end of the season, will have handed over $1.5 million to pickers—in cash. The industry is valued at around $15 to $20 million in Canada, though the exact number is unknown, given that many transactions go undocumented and profits fluctuate drastically from season to season. There already aren’t enough pickers to cover the hectares of burnt land, so much of the potential crop remains untouched.

“You may have ten times more acres burning up, but if no one is out there to pick it, it doesn’t matter,” says Brenton King, owner of Pacific Rim Mushrooms in Richmond, BC. King says some companies have resorted to importing workers, many of them without permits. People familiar with the industry told me they estimate that 30 to 40 percent of international workers are picking without a working visa—a fact some buyers exploit by paying less to those they know don’t have proper documentation.

The provincial government has few regulations for non-timber forest products (often called NTFPs), including morels. Pickers are legally allowed to harvest on Crown land, which comprises 95 percent of all land in BC. The province’s website lists some basic rules for harvesting: don’t disturb the soil surface, respect the rights of First Nations and private property owners, don’t pick in provincial or national parks or in ecologically sensitive areas. Without enough conservation officers to deploy to the affected areas, however, these guidelines are rarely enforced.

The province has no plans for further regulation, and its past attempts to regulate NTFPs, such as pine mushrooms in Central BC, were eventually repealed. “Our society is focused on industrial commodities,” says BC ecologist and morel researcher Michael Keefer. NTFPs don’t hold a candle to major industries like timber, even though the annual worth of all NTFPs in Canada was estimated in 2006 to be as much as $1.26 billion.

Companies like Wild West Foragers have mixed feelings about the possibility of provincial regulation. On the one hand, it could secure rights and protections around payment, says co-owner Celia Auclair. It would also increase picker safety by ensuring all pickers are required to have a GPS and bear spray on their person at all times.

But more regulation might also de-incentivize pickers, who would be forced to reveal the location of their proposed picking areas. Regulation could come at a steep price; because of morels’ ephemeral nature, pickers and buyers often frequent several burns per season. They worry they’d be obligated to pay a permit for each site, drastically upping their overhead costs.

In the meantime, Wild West Foragers try to impose some standards. They won’t buy from people who are using meth close to their camp—sometimes, some pickers are clearly high on something—or people who illegally forage in a neighbouring provincial park. The buyer’s tent run by Auclair and her partner Ben Patarin has a reputation on the burn for being picky but paying well—up to $1 more per pound than other buyers on a given day.

At the end of that first day, we go to Auclair with our three half-empty crates. Petite but wiry, she lifts the lid off Marte’s crate and sighs audibly. “First-time pickers?” she asks. “You need to cut directly below the cap.” She tears off the extraneous material. “And see this?” She holds up another mushroom. “The gills are too open, which means it’s becoming old.” She rifles through some more. “This is way too old. And these,” she tosses out a salmon-pink mushroom, “are rotten.”

I’m all too aware of the line of pickers standing behind us; I can feel the heat of their eyes on our backs. Auclair offers to help us go through the rest of our haul but we politely refuse, taking the remaining mushrooms down the road to Niall Sherwin’s buying station. He gives us a similar rundown but is willing to take more of the duds than Auclair was. At $6 per pound, I come away with $30.

Later that night, Felix asks the same question over the fire. “So, how was everybody’s day?”

The three of us are quiet, and even Sophie seems hesitant to offer anything up. “I didn’t have a good day,” she says. “Ali did, though.”

“Oh?” Felix asks.

When Ali stays quiet, Sophie speaks for her. “She picked seventy-five pounds.”

I make the same calculation everybody else does. $487.

Felix congratulates Ali, places the cauldron on the fire and walks away.

The next day at Sherwin’s station, he praises me for doing better. I thank him, but my thoughts are elsewhere. I can feel blood drying on my leg where a stick forked through earlier in the day. My lips are so chapped I can’t feel them when I lick them, and my head thumps with dehydration. Sherwin hands me a complimentary Coke and the sugar lights my tired body up like a sparkler for a few moments before fizzling out again. I wipe my mouth with the back of my hand, which looks like flesh-coloured bubble wrap because of all the bug bites.

It isn’t until Sherwin discretely hands me the slip of my receipt that my mind sharpens. Thirteen pounds, $86. Better than yesterday, but I can’t help but think about what Marte and Jonas’ slips must have said; within ten minutes of our first scout, Marte already had half a bucket full. I had barely covered the red plastic bottom of mine.

I don’t have much time to think, however, because the person behind me starts loading his crates onto the table, nudging mine off. I recognize the elderly man as Lou, a famously proficient picker who’s been working the same area for years. I pocket my money and head back to the car.

But then a white pickup truck pulls up and three uniformed men hop out. “Everyone here got permits?”

The men are part of the Secwépemc Territorial Patrol. In 2017, as the Elephant Hill fire began to grow in size, eight bands of the surrounding Secwépemc Nation came together to form the Elephant Hill Wildfire Recovery Joint Leadership Council. “We as the Secwépemc people have been on this land for the last thousand years,” says Ronald Ignace, chief of the Skeetchestn Indian Band. “Elephant Hill is where we get our fish, it’s our hunting area, an area where we get our food plants. It is like our Save-On-Foods.” The eight bands decided to work together to minimize the impact of the fires and associated industries like morel picking.

In the absence of provincial regulations, the bands “woke up” Secwépemc law, allowing them to govern by Indigenous laws versus colonial ones. Thankfully, Ignace says, the provincial government was agreeable, with some members working within the council as government representatives. Before mushroom season began the following year, an offshoot of the council formed the Secwépemc Territorial Patrol, or STP, and, working with a nonprofit called Forest Foods, created a management strategy for the expected influx in morel-pickers. “Wherever mushroom-pickers go, they devastate the land,” Ignace told me. “They leave a mountain of garbage behind.”

Most pickers would object to this characterization; indeed, many of the ones I met were careful not to disturb surrounding ecology. And other than litter, studies show morel-picking is a sustainable practice. Still, transient pickers like myself often aren’t around long enough to witness the long-term effects of our harvesting, on both the environment and nearby communities.

I met a mushroom-picker of Cree and German descent, originally from Grande Prairie, AB, who had been living off the industry for twenty years. But he said that one burn near his reserve, in 2014, attracted upwards of three thousand morel pickers and the subsequent mess was terrible. He wished there had been some sort of program like the STP in place to hold pickers accountable.

In fact, the STP has become the first authority in British Columbia to, in effect, regulate the industry. On Elephant Hill, pickers are required to buy a $50 permit, and buyers a $500 one, in exchange for the right to extract natural resources, plus an information packet and waste removal at designated campsites.

By the end of the season at Elephant Hill, the patrol would remove 12,500 gallons of human waste and 14,760 pounds of garbage at designated sites, all of which would otherwise have been left on the land. By mid-season the organization had also recovered four people lost in the bush and responded to twenty-five emergency situations, including two bear encounters. The previous year, under a less formal recovery program, two pickers died of exposure, according to the patrol’s information packet. “I think we’ve proven ourselves to be good caretakers,” says Ignace.

Back at the buying station, I watch a conflict unfold between Lou and the patroller checking permits. At eighty-six years old, Lou’s been picking for fifty years without ever paying a penny and he’s reticent to start now. While many pickers on Elephant Hill are amenable to the Secwépemc Nation’s system, there are still some like him who buck at the idea of constraining an industry that’s always been “wild and free,” says Patarin.

At least one company, Pacific Rim Mushrooms, decided not to participate in the program; owner Brenton King told me that it could just be a cash grab. But Wild West Foragers’ owners, who did participate in the program alongside nine other companies, doubt that the Secwépemc Nation turned a profit, given the cost of operations. “At the end of the day, they provided us with services that were pretty useful,” says Patarin.

Since the program isn’t provincially mandated, there are no legal consequences for those like Lou or King who don’t comply. After several heated moments, Lou returns to his car while the patroller heads over to our group. His fellow patrollers ask him what happened and he shrugs. “The man’s eighty-six years old. We told him not to worry.”

A rumour circulated in the burn later that week: Lou himself had gotten lost. Knowing it was better to stay put than continue to wander, he spent a night in the woods and had already picked a couple crates the following morning by the time members of the STP found him and brought him safely out.

The permitting program is a small, albeit significant, part of a much bigger plan. For the Secwépemc Nation, the morel patrol represents a step towards asserting jurisdiction over their territory and restoring its environment after decades of provincial mismanagement. “We have to re-engage with [the government] to utilize traditional knowledge to bring back the forests in a healthy state,” says Ignace. This means reintroducing practices like controlled burns of forests to prevent large-scale fires and increase biodiversity.

Forest Foods project manager Shelby Leslie agrees that one factor contributing to destructive fires is BC’s focus on for-profit monoculture—the practice of growing a single crop. Without deciduous trees working as the land’s irrigators, Leslie says, there are millions of hectares of high-density pine forests, which, with the impact of climate change, leads to swaths of trees that are tinder-dry and can turn into mega-fires.In the past, “timber companies, encouraged by the province, have created plantations and not necessarily forests,” he says.

Thanks to the STP’s success in its first summer, the provincial government has sanctioned the Secwépemc to move forward with a ten-year proposal to regenerate biodiversity, and several other Nations are adopting their own stewardship programs. Still, Ignace fears the damage is far from over. “I believe the mother of all fires has yet to happen here in British Columbia,” he says.

I begin to see morels everywhere. I see them in the folded bark at the trunks of trees. I see them in the embers of the fire. I see them on the backs of my eyelids as I spray repellent on my face. I see them in my dreams. I suppose this is the brain’s way of remembering, of adapting to what’s important. But now morels are just about all I can see. They even appear more aesthetically beautiful to me, no longer damp, shriveled fungi, but hearty, diamond-shaped fruit.

We’re getting better at finding them, the morel patches, but never the ones I hear about in low tones at buyers’ tents, the patches rumoured to have so many mushrooms you can’t walk without stepping on some.

Then one day in the forest, mid-season, the ground becomes spongy and a break in the trees indicates a body of water—something boggy, by the smell of it. I notice an imprint in the ground, as big as my face, with five divots around it. A bear print. I’m about to turn around when I see, beside the print, the little black snout of a morel pushing up through the dirt. I run my eyes over the landscape, my mouth falling open. There are hundreds, maybe thousands.

I cut mushroom after mushroom, discovering the best places to find them are the places you’d least like to be: the underside of rotten logs, inside mysterious burrows, beneath a net of barbed shrubbery. Mosquitoes come in hoards and I no longer take it as an offense but a clue; if a plume rises when you step, you’re almost certain to be near a good patch. I’m so engrossed in the picking, almost a whole bucket filled, that I don’t notice how far Marte and Jonas have gone. About half a bucket later, I hear something: a deep growl. I stay low, frozen beside a fallen log, my paring knife held out in front of me. The noise changes to a great cracking sound, followed by a resonating thud: the distinct sound of a falling tree. I continue to pick, but every time a branch breaks I jump.

When I reach the packs to dump my second bucket into the crates, Marte is already there, complaining about the bugs. I’m about to try and convince her to stay, there’s so much still to pick, when Jonas comes bounding through the forest. “We have to go—now,” he says. “There was a bear following you. I was behind you and saw it and then it turned to growl at me.”

We fumble to attach the crates to the packs, but my hand slips and one of my crates opens, spilling mushrooms out. They roll on the ground like loose change. A hundred bucks, maybe more. I scoop them frantically back into my crate, ignoring Marte’s plea for me to leave them, and dump the last of the mushrooms in. “Ready,” I say.

On the drive back to camp, Jonas turns the music down. “Can I tell you guys something terrible?” he asks. “When I was backing away from the bear, I stopped to cut a few big mushrooms at my feet.” That is terrible. I understand.

Soon enough, we too start to give our spots vaguely specific names that only we understand: Avocado, Baby Patch, Three Bear, Bog One, Bog Two. We beetle around on logging roads, scouting for places where there are no other cars. Sometimes we hike into areas that look promising, only to find them barren or, worse yet, recently picked. Other times we chance upon bountiful patches feet from the car.

Our hauls steadily increase, which earns us a certain amount of deference at the buyers’ tent and even some curiosity from other pickers. After a particularly lucrative day, Sophie asks where on the burn we were and I find myself giving a cryptic answer.

But just as we’re starting to get the hang of things, the mushrooms transition—the species we were used to picking fruits less and less, and a new type sprouts up more and more. Advice for where to search for these heavier, more bulbous morels is contradictory; some people tell us to go to lower elevation, while others say to stay high.

The temperature spikes to thirty, bringing even more mosquitoes. I come back to camp each evening sweaty and sore, the corners of my mouth numb from Deet. Still, when Felix asks his routine fireside question,“How was your day?” and I find myself short compared to the others, I chastise myself for not working harder.

One hot day, late in the summer, I convince Marte and Jonas to go back to a patch that worked well for us earlier in the season, though the road into it is somewhat treacherous, covered in fallen trees and heavily rutted. I feel certain today will be my day: the day I finally pick more than twenty pounds. It’s all I can think about.

On the narrow road in, my car lifts up over what I presume is another fallen log, when I suddenly hear a buzzing. Ten or so bees lift from the underside of my car and begin to orbit it angrily. I’ve just run over a beehive.

I contemplate out loud how we should get to the patch, given this new development, and Marte gives me a strange look. She reminds me that I’m allergic to bees. “I know,” I say, “but think of how much money we could make.” I can see Jonas weighing the options too. But Marte is firm. She doesn’t think it’s a good idea. Finally I agree, throwing the car into reverse.

We end up finding a few small patches, but frustration clings to me. When the temperature rises even higher, I can’t take it anymore; I ask Marte and Jonas if they’re willing to sell their mushrooms now and take the rest of the day off. They say yes without missing a beat.

Back at camp, I’m surprised to see Felix sitting by the fire pit. I join him and ask how his day went. He and Andre picked about forty-five pounds each, he tells me.

The disappointment in his tone only exacerbates my feeling of inadequacy; his bad day is still double my best. “That’s great,” I manage. Felix agrees, but adds: “It’s just silly because if I don’t pick fifty pounds, I feel like a failure or something.” There’s something in the way he says this that plants an idea in my mind.

It’s as though Felix’s admission released me from a game I wasn’t aware I was playing. I think back to the questions: How was your day? How much did you pick? Only now do I realize how inextricably linked those two questions are. And it’s not just about the money; when I don’t pick as much as I want to, I feel a lack of self-worth. I feel like a failure. Judging worth based on profit is dangerous, I realize, looking at the dead trees around me. If we are to have any chance in surviving this changing world, we are going to need a new value system to measure ourselves by.

I’m shocked by how quickly my focus on money took over everything else: my thoughts, my friendships, even my own safety. Just a couple of hours ago I had been willing to risk anaphylactic shock in order to turn a profit. This myopic obsession with material wealth was responsible for our ruined climate in the first place. Now I am beginning to understand why—it’s so ingrained in us, we often don’t even know how much it drives us until we’re at the edge of something extreme.

Within three days of that fireside chat, Marte and I decide to leave. The season is winding down anyways; Niall Sherwin told us his company would be moving him further north in a week or so, where morels were just beginning to flush.

Marte and I are mostly quiet as we drive through the burn back towards Clinton. The forest doesn’t appear as menacing to me as it did on my drive in, though it certainly still looks as apocalyptic.

I watch tree after blackened tree scroll by and I remember something one of the other pickers said at a bonfire the other night. He became irritated when the conversation turned, as it almost always did at those gatherings, to the best places to find the mushrooms. “Everybody says something different. Go high, go low. Go dry. Go swampy.” He raised his voice. “The thing we don’t say is that it’s totally fucking random. The best advice, in my opinion, is to just keep going.”

I agree, although I’d make one amendment: I think it’s as important to know when to turn back. When to say enough is enough. This isn’t worth it anymore.