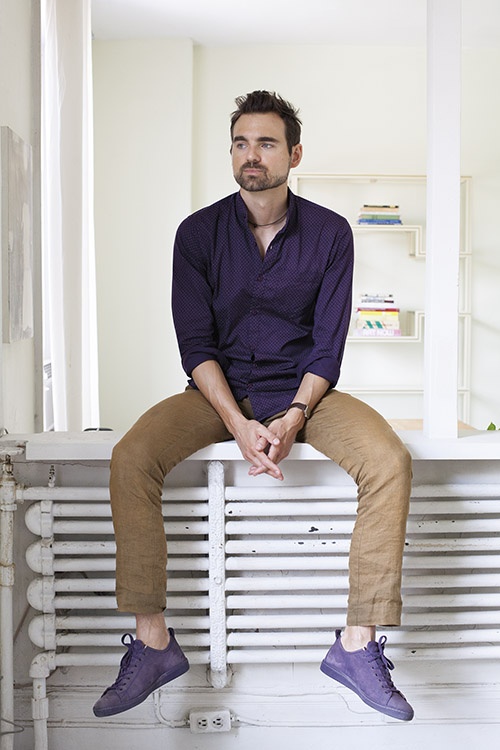

Photo by Alana Riley.

Photo by Alana Riley.

Question and Answer

New fiction from Krzysztof Pelc.

If you’re lying in bed, which side does your spouse sleep on?

Does your spouse love you?

How do you know?

The list we have is endless. And they keep adding to it. I guess they have to, to stay ahead. You’re actually meant to add in some of your own, some unexpected ones, as a way of throwing people off. You think of good ones on your morning drive, you practice them in front of the mirror. Though most of the questions are boilerplate. What’s his favourite meal, who was the officiant at the ceremony, how did you get there, did someone drive you?

Often, you’re not even listening to the answers, you’re just looking at their hands, looking at their eyes. Hunting for discomfort, for any sign of where to push.

“If you’re lying in bed, which side does your spouse sleep on?”

With that one, you’re looking for this involuntary hand movement, to the left or the right, as they picture themselves lying in bed with their spouse beside them. If they’re just sitting there too long trying to remember, something’s off. And then you know to push further.

It’s an odd power to have. They make their sacred vows, and then we have a second look. Most often, it’s because of a neighbour’s tip. Neighbours are always giving each other up. Wielding that power, it can be a draw. You don’t know whether you’ll get off on it until you’re in there, deciding who stays and who goes, whose love you deem legit. Some of the officers, they get off on it. But not me. Not after the first while, at least. But yeah, some do.

Often the predictable stuff is the most revealing.

“How did you two meet? Who first spoke to whom?”

That one’s a gift question. But only a gift for the legit cases. The legit cases revel in it. All couples have their creation myth, and they love to tell it, they never get bored of it. We’re not friends, and we’re not here to have a good time, but still they relish it. They break into a smile, a giggle. And that’s what you’re looking for, that giggle. That’s one answer that should look rehearsed. Because the legit couples are asked all the time, by aunts, by friends at dinner parties—they have a routine, they jump in on cue, they take turns, it goes her, then him, then her again.

“If you’re lying in bed, which side does your spouse sleep on?”

“He doesn’t.”

I’m looking for the hand gesture, that vague movement in either direction, but this makes me look up. I haven’t really noticed her until that point. It’s early morning, we’re just getting started. She’s attractive. Objectively, I mean. Mad curls, these fine arched brows. Both of them nicely dressed, polite to a fault.

“Excuse me?” I say.

“He doesn’t,” she repeats. “He doesn’t sleep. He paces around. He gets up and sits in the reading chair. But he doesn’t read, either. He goes to the window and looks out on the street, at the sky. I pretend to sleep, but I just count the hours that he’s up.”

She’s from Morocco. (“Where were you born? Where was your spouse born?”) She’s the sponsor, her parents immigrated when she was a kid. Owns a condo, a car, high-profile job. He’s from Egypt. Quiet type, recently arrived, firm handshake, unemployed. They met through friends, she says. Gift question, but not to them: no blushing, no smile. She says it matter-of-factly.

Sometimes you’re there to protect them, because no one else will. Like that middle-aged woman from the suburbs who walked in one day with her twenty-nine-year-old husband, freshly arrived from some unenviable land of oppression. Met online, married six weeks later. What do you tell that woman? “Ma’am, you’re being played”? “Ma’am, he’ll be gone in a week”?

She takes offense. How dare you, she says. She quotes from memory the love letters he’s sent her. She says we have no right. Until finally the realization seeps in, and she slumps down a bit. Even though she knows, still she pleads their case. Who are we to judge, she cries. But that’s the job, right? To judge.

That was a long time ago, and this isn’t that. This woman, the one with the fine brows, she knows exactly what she’s doing. He, by contrast, says little and keeps glancing over at her for guidance.

But here’s the thing. All her answers are off, and she’s aware of it. She doesn’t know his favourite meal is the fattoush made by his mother. Doesn’t know about his six cousins, or that two of them are dead. Doesn’t know his favourite movie is Love Actually. Worse, she guesses Star Wars. Because women who don’t know always guess Star Wars—I guess it’s a reasonable play on the odds.

She knows I know, too. But she doesn’t let on, she knows she shouldn’t.

The questions are designed to screen for “marriages of opportunity.” That’s what they’re called. I know, what isn’t, right? Marrying the varsity swimmer for his broad shoulders, getting with the chick with the family connections: what do you call that? Take me: I once got lured across a room by a flowered dress and a madcap laugh. I knew an opportunity when I saw one, and I grabbed it. Never looked back. That was thirty-six years ago. Well, those aren’t the opportunities Immigration Services cares about. The questions, the hunt for discomfort, for second-guessing, they’re meant to distinguish those opportunities from this one.

They used to do house visits. Now they hardly ever do. No resources. It’s like in medical shows where a team of ER doctors all go into a patient’s home to sniff around the kitchen cabinets for clues to some weird illness. Never happens, right? Same here. Those rumours about la migra showing up early Sunday morning and going through your underwear drawers? Make-believe. They can’t afford the overtime. No, it’s all about the questions. It’s about the newlyweds game, played in small rooms under fibreboard ceilings and halogen lights.

“How do you know he loves you?”

She’s silent for a moment.

“He says, only I help him forget.”

I don’t press it. Truth is, I feel a little uneasy. It’s a good answer, I make a note of it.

The hundreds of questions are really all the same question. They’re all asking, who are you doing this for? And if their answers, their hand movements, their fleeting looks, the way they point their feet, if it all says, I’m doing it for him, I’m doing it for her—well that’s the wrong answer. The do-gooders get picked off right away. This is what I try to tell the woman with the fine brows, this is what she needs to understand. She gets it, I think. She nods.

You might think the questions are about whether they’ll stay together, that that should be the test. But don’t most marriages fail anyway? Maybe that middle-aged woman from the suburbs was right. Who are we to say? I think about that woman a lot these days, though that was a lifetime ago. I’ve retired since. And my Maggie’s gone. She was the summer dress and the madcap laugh. My opportunity. They said it was an embolism, a tiny clot that had travelled up. She wouldn’t have known it was happening. When I got the call, I was at work, putting couples through the newlyweds wringer. I used to be able to play back Maggie’s laugh in my mind.

An opportunity like that, it doesn’t happen twice.

And then, I guess I switched sides. The lawyers call it “coaching services.” Sounds like minor-league baseball, right? I don’t talk about it with the guys back at the office, though I still see them around. They’d laugh, they’d call me a softie. Or worse, a fink. And maybe they’d be right. Though the old timers, they’d understand. You see enough of those cases and you realize the breadth of the grey zone. And then you decide what side you want to be on. And now, I want to be on this one.

“What’s the colour of your sheets?”

I ask them one last time.

“Beige,” they respond in unison.

“What’s his favourite movie?”

They laugh. Love Actually, she says, shaking her head, and her curls flit about.

We’ve gone through the whole roll half a dozen times, I’ve repeated all my advice until they’re tired of hearing it. We’ve done the full simulation; we’ve had two weeks at it.

“You’re ready,” I tell them.

They remain in the back seat a bit longer. I notice his hands shaking a little. I know what he’s thinking. He’s thinking of what happens if they fail.

By now I know all their answers, too. I know how both of her parents moved back to Morocco, while she stayed. I know that her best friend’s name is Viola, that she’s a journalist, and that she’s the one who found me. I know the place they’d like to go on honeymoon: the Yukon, because he’s never seen snow and he dreams of dogsledding. I also know both of his cousins died on the same day.

They gather their things. She kisses him. It feels like she’s doing it for me, in some final attempt at convincing me—but it’s not a lover’s kiss. You get good at telling, you know? It’s a mother’s kiss to a child. But I look away all the same; despite myself, I blush.

I tell them not to kiss in there. I tell them to hug instead, because kisses are too revealing. And besides, I don’t need convincing anymore. I’m on their side.

They get out of the car. Nice kids, their whole lives before them. Though I know he’s seen a lifetime’s worth already. And she knows, too, she knows better than anyone. The immigration office looks dim, the windows lit up by halogens, and those awful fibreboard ceilings. They look like operating rooms. The doors are tall and heavy, but she takes his hand, they climb the steps towards them and disappear inside.