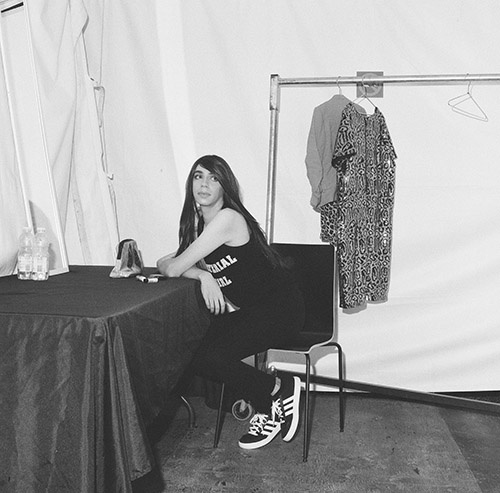

Photo by Alana Riley.

Photo by Alana Riley.

Funny Girl

Rosie Long Decter follows Montreal comedian Tranna Wintour as she does her bit.

Tranna Wintour is in a green room backstage, putting on her lipstick. There’s a knock at the door and she begins making her way through a dimly lit hall toward a cheering crowd. She walks with confidence, in a flowing blue dress; tall and angular, with cascading black hair, she could almost be a model on a runway. A stagehand stops her—“I have Mariah Carey on the phone”—but Wintour shoos her away: “I don’t have time to deal with her crazy.” The MC announces her arrival and Wintour finally steps through the door—and into her bedroom, where she promptly crawls into bed and falls asleep, her lipstick shining.

This is the start of Wintour’s first-ever comedy special: a twist on the typical stand-up opening, but classic Wintour. She plays with the line between fame and fantasy, divas and wannabes—the technique is even built into her name, a play on the famously brilliant and terrifying Vogue Editor-in-Chief Anna Wintour.

Wintour has been a fixture of the Montreal scene since she started doing comedy in 2013, but that line between local favourite and national star has recently become thinner than ever. After releasing the special in April, she was named the number-one Canadian comedian to watch by CBC and selected as one of Just For Laughs’ “New Faces,” a coveted shortlist, in July. But unlike most Canadian comics who make it big, Wintour, who was born and raised in Montreal, has no intention of heading south of the border.

It happens to be a good time to be a young comedian, especially—for the first time—if you aren’t a straight, white, cisgender man. The last five to ten years have seen a huge spike in comedy production, from podcasts to Netflix specials to HBO half-hour “dramedies.” This increase in production has also allowed a wider range of forms and voices to reach mainstream audiences.

In 2015, Vulture’s Jesse David Fox dubbed this era the “Second Comedy Boom,” the first being the clubs heyday in the eighties. He argued that the internet and the expanding TV industry have made comedy more accessible than ever to a generation already primed for super-fandom thanks to childhoods spent watching the first boom (SNL, Seinfeld and all their imitators). A 2012 Comedy Central survey found that millennials are the first generation that sees comedy as more important to their identity than music.

Wintour, though, didn’t grow up watching Seinfeld—or any comedy, really. She was busy watching Madonna. “Music, especially pop music and broadway and musical comedy, that was really my influence,” she says. She’s only been doing stand-up for six years, which is next to nothing in comedy. “Since I was a really young kid there was always this performer, creative energy, in me that for a long time I didn’t know how to channel or express,” she says.

That only changed when she reached adulthood. “As I came to an understanding of myself as a trans person, that gave me the confidence that I needed to look at myself as a performer as well, and to start to figure out how I wanted to express myself creatively.”

Everything clicked when she discovered Sandra Bernhard, a classic seventies comic famous for her work on Roseanne but who first made her name in her musical one-woman shows. “She sings and acts—everything that she does is so theatrical and satirical and multi-layered,” says Wintour. “When I discovered her comedy, it was like ‘Oh my god, this is the answer to the question that I’ve been asking my whole life.’…Even though I’d never done stand-up, I just knew that this was it.” The thing is, when your jokes differ from the norm, you’re also changing what’s considered funny in the first place.

I saw Wintour co-host a comedy night back in the spring at NDQ, a small dive bar tucked into Montreal’s Little Italy, known for its Sunday-night karaoke and excellent pizza. A local haunt for young queers, the bar was packed with chatty twenty- and thirty-somethings; there was so little space that I grabbed one of the last seats on the bowling alley that doubles as a stage.

It was the March edition of Stand Back, a monthly comedy series devoted to women and LGBTQ performers, co-organized by Wintour. The night featured a mix of stand-up comedy and experimental sketch. At Kadi D.’s jokes about the bleak dating prospects in Montreal, the crowd laughed with familiarity, and they cheered at Eman El-Husseini’s story of realizing she was queer when she fell for her future wife.

In between each act, Wintour came on stage to warm up the audience for the next performer; at one point, she tried guessing the astrological signs of audience members. The bit is genuine—Wintour loves astrology and gushes about it frequently in her act—but it was also a clever way of connecting with that specific crowd, given astrology’s popularity in queer communities. It’s an alternative meaning system, a way of divining the world for people who are frequently told by the world that their sheer existence is meaningless, and Wintour knows this. If she guessed wrong, she would keep going until she was right; and when she was right, the whole crowd cheered, like she was cosmically connected.

Between cabaret shows, Stand Back and her film series Trannavision, Wintour’s footprint is all over the city, always in conjunction with friends and co-conspirators. At each Trannavision screening, Wintour selects a cult classic film and invites other comedians to join her in providing commentary over the movie as it plays; past screenings have included horror satire Scream and J-Lo rom-com Maid in Manhattan.

Ariana Sauder, a fan of Wintour’s for years, calls Trannavision one of her favourite nights in Montreal, thanks to Wintour’s ability to make the crowd love each movie as much as she does. “She has a way of talking about TV, movies or music that is funny even if you aren’t passionate about, or even familiar with, the thing she is joking about,” Sauder says.

It’s maybe ironic that one of Montreal’s most popular Anglophone comics doesn’t even particularly like identifying as one (a comic, not an Anglophone). “I always sort of gag at the word ‘comedian,’” Wintour says. “It’s just a word that I personally have a lot of negative associations with.”

The last thirty years of mainstream stand-up have largely consisted of white men complaining into a microphone. The subjects of the complaints change, and the styles range from Seinfeldian observational humour to Louis C.K.-esque confessionals, but the form has mostly stayed the same.

The recent broadening of boundaries hasn’t been limited to Montreal. The new Hulu comedy Pen15, for example, is an unsettling take on middle school where Maya Erskine and Anna Konkle play themselves as thirteen-year-olds, surrounded by a cast of actual thirteen year-olds. Los Espookys, the absurdist HBO show, sees a group of friends starting a “horror business” where they create artificial terrifying experiences for clients, while their real lives verge on the actual supernatural (one character has a water demon inside of him; another can make people magically fall through beds). Meanwhile, men like C.K. are starting to face consequences in an industry that previously treated them like gods.

Wintour is very aware of these bigger changes, she tells me over the phone. Bernhard got her start in the seventies, and “as much as it’s still very male-dominated, back then it was a hundred times worse. I don’t know if I would have been strong enough to handle that back then.”

Comedy and music have a lot in common. Both require performers to build a persona, to sell a version of themselves—unlike actors, who build careers by playing other people. But where musicians position themselves as icons, comics become their audience’s friends. Now, thanks to the proliferation of podcasts and specials, fans have more ways of spending time with their favourite comedians, learning all their bits. If millennials are defining themselves using comedy, maybe it’s because, where a musician can inspire from a distance, comedy needs you to connect.

Wintour’s work bridges the two mediums, and it often centres around her own connections to various Broadway and pop stars. The first comedy routine she ever wrote was a Bernhardian one-hour show, not realizing that most comics just start with a five-minute set. Her special features a scene in which she lights a candle at the altar of a Yentl vinyl, and then stares at herself in the mirror, repeating Barbra Streisand’s name three times. “Fuck, it didn’t work again,” she mumbles.

The special then cuts back to her stand-up, where she launches into a riff on Bette Midler: “Wind beneath my fucking wings—everyone’s wedding song circa 1991,” she says, to a giggling crowd. “It must have been cold there in my shadow, to never have sunlight on your face,” she sings. “Being in a relationship with Bette Midler is a nightmare!”

Wintour’s fascination with divas runs even deeper than it first seems. She turned her Just For Laughs show in July into a tribute to a Canadian belter, titling it Dear Alanis: A So-Called Musical Comedy. After a long piano introduction, she walked out onstage at local strip-slash-cabaret club Café Cleopatre. The crowd gave a loud round of applause. Unsatisfied, diva-style, she motioned for us to clap louder—so we did.

She opened Dear Alanis with an anecdote about a “witchy” former co-worker named Margot, who was allegedly a receptionist for Morissette’s dentist and, as Wintour recounted with faux seriousness, told Wintour she would also be a star. But Wintour is adept at weaving in and out of the realm of serious emotion. She made clear that this show wasn’t just intended to get laughs.

In one of the most vulnerable acts I’ve seen on a stage, Wintour introduced a rendition of “Unsent,” in which Morissette writes letters to former lovers, with her own letter to a boy who broke her heart. She had the house lights turned on to check if the boy was in attendance, and walked through the crowd looking for him—“Fuck it, is [he] here?” she asked, calling him by name (that name was meant to stay inside the theatre). Deciding he wasn’t there, she made her way back to the stage to read the letter: “Dear Daniel,” she began—a different name. The crowd laughed. And then, with the earnestness of a rom-com leading lady, she told him, and us: “I’m sorry I fell in love with you.”

In the hands of a less deft performer, the segment could have easily been a confusing mix of catharsis and art. But Wintour didn’t reserve the therapy session for herself. She proceeded to ask audience members to yell the names of their shitty exes: “Charles!” someone called out. “Be thankful that you ditched that cargo!” Wintour replied.

Wintour’s comedy feels deeply old-school; her brassy style calls to mind speakeasys and even vaudeville. But blending music, pop culture and stand-up is distinctly contemporary, an explicitly feminine and queer sensibility shared by many in the current moment.

New York, in particular, has become home to a wealth of queer and trans comics who perform in cool Brooklyn bars, as opposed to classic comedy clubs. Eman El-Husseini, a Montreal comic now based in New York, says she’s really noticed a shift in the last two years, in the wake of the MeToo movement. “Powerful white men getting arrested—nothing excites me more,” she says over coffee with her wife, Jess Salomon, also a comedian. The duo perform together as the El-Salomons, a Palestinian-Jewish married couple whose sheer existence guarantees hate mail. “When I started comedy, my boss was full-on openly racist, sexist—hated female comics,” El-Husseini says. “It was the norm.”

Wintour, the El-Salomons and others who have come from their Montreal scene tell their jokes from specific perspectives—whether, for El-Husseini, it’s the experience of coming out as a Muslim woman, or, for Wintour, of dating as a trans woman—that they don’t compromise for any audience.

Of course, it’s a long way from Montreal lesbian bars to a half-hour HBO series or a sold-out show at Madison Square Garden, but shows like Pen15 and Los Espookys are evidence that the industry is taking note. Rising comic Joel Kim Booster likely won’t be making as many graphic sex jokes on his new NBC sitcom as he does on Twitter, but his Twitter hasn’t gotten any tamer since announcing the show, either.

The increasing fragmentation of TV viewership means that niche audiences matter more, too; there’s more space for a show like Comedy Central’s The Other Two to lampoon gay Instagram culture without having to explain it to or soften it for straight viewers. Ultimately, TV and comedy clubs are still profit-seeking industries—these comics will only find support as long as they continue to turn profits—but more and more of those profits are reaching creators like Wintour.

The boom has been slower to find its way north. Canadian comedy is dominated by Just For Laughs and the major TV networks and, though those old institutions are making efforts to include new voices and faces, comics are still flocking south to find opportunity.

“Our best stand up to their best, no problem,” says D.J. Mausner, a collaborator of Wintour’s. “But…in the States there’s fifty channels you can pitch a pilot to; in Canada there’s two or three,” she says. “It’s like, you have to deliver us a pitch that is tonally perfect for our network, and…if it’s not then we’re not taking a chance on you because we know what works. So they bring over shows from the States, they have a million and one cop dramas of white men solving crime, and comedians continue to struggle to make ends meet. I mean, hell, Canadian comedians aren’t even treated as well as American comedians at Just For Laughs.”

Just For Laughs recently came under fire for that. In February, SiriusXM announced a partnership with the festival that would mean airing international comics on their “Canada Laughs” radio station, when it had previously been an exclusively Canadian channel. It was also one of the biggest and most reliable sources of income for Canadian comics, thanks to the hefty royalty cheques that come from airing comedy albums on satellite radio. In the end, Just For Laughs reversed the decision.

Still, it’s a small victory. Mausner points out that there’s no infrastructure for generating stars in Canada, no late-night circuit whereby comedians can show off their bits to millions. And the fact that there are so few huge institutions in Canadian comedy means that when you lose access to one, you’re basically out of luck.

Mausner, who was the 2017 winner of its Homegrown Comics competition, announced in 2018 that she wouldn’t work with Just For Laughs due to the festival’s inaction over sexual assault allegations against its former president, Gilbert Rozon. Rozon had been initially charged with sexual assault in 1998 and has had more than a dozen accusations against him since then, but he remained president of the festival until 2017. Mausner’s boycott sought to highlight how the festival had continued to employ him while aware of these allegations—it never even released a statement about its complicity after he left. The festival has since implemented a sexual assault policy, but Mausner’s boycott stands. Seeking more opportunities, she recently moved to L.A. The El-Salomons concur with the bigger complaints. “They love you so much more when you leave,” El-Husseini says.

Wintour has done the opposite: she has stayed put in Montreal and built a community of collaborators. “Tranna’s created her own scene,” Salomon says. In addition to her extensive roster of regular live shows, Wintour co-hosts CBC podcast “Chosen Family” with creative partner Thomas Leblanc. The pair brought their Britney Spears tribute show to Montreal Pride this year. “I sort of feel like I’ve had to put things together for myself,” she says, “because if I wait around for people to make what I want happen that could take forever, and it might not happen.”

Though English is her first language, Wintour is bilingual and has recently branched out into the Francophone scene, which has increased her profile and opportunities significantly. As Mausner points out, the Franco comedy industry is arguably better developed than even Toronto’s comedy scene. “They have their own star system, they have people who go over to France, they have ZooFest, which generates immense amounts of money,” she says. “It is its own industry, and thank god they’ve got Tranna in there.”

There are certainly comics in Canada making exciting and well-loved work, if not lots of cash. Baroness von Sketch Show is one of the highest-profile CBC programs on air, and it’s written by and about women, including queer women. One of the group’s most famous sketches pokes fun at the self-seriousness of feminist reading groups and will feel familiar to anyone with a gender studies minor. A second sketch show is premiering on CBC this fall from the young comedy troupe Tallboyz, whose sweet and satirical work explores race and masculinity. And in Montreal, anti-oppressive events like Wintour’s Stand Back and Tatyana Olal and James Brown’s Squad Laughs have become staples of the scene.

Just For Laughs’s lineups are still dominated by Americans, but El-Husseini and Salomon say they at least felt a real change in the management last year, after Rozon and his closest staff were all ousted. A male comic made lewd comments to Salomon at the 2018 festival; when she told him the next morning that she would have him evicted from the festival if he did it again, he told her he’d already been kicked off the lineup—because someone else had complained. “I couldn’t believe it,” Salomon says. “Two years ago, that was unheard of,” El-Husseini adds. “To remove a comic that was doing a big thing at the festival because of inappropriate behaviour—as if!”

A lot of Montreal artists face a catch-22: affordability versus opportunity. But Wintour says she doesn’t see it that way. “I don’t feel like Montreal’s holding me back,” she says. “I think it’s the perfect home base.” She insists that she wouldn’t be able to do what she’s doing anywhere else, in large part because Montreal is such a livable city. “If I moved to Toronto, or L.A., or New York, I would have to get a day job and I think that would be a bigger setback than anything else. Things only really started coming together for me when I left my day job three years ago.” In any case, the internet makes it easier to be based anywhere. Wintour says she’s had collaborators from all over reach out and ask her for work.

Wintour is also trying hard to prioritize community over competition—sometimes hard to do in precarious industries. “I made a really conscious decision at the end of last year to let go of this constant comparison that a lot of creative people…fall into,” she says. “For me, this might sound really corny, but I always go back to this Dolly Parton quote—her whole thing is don’t get so busy making a living that you forget to make a life,” she says. “I’m really just trying to stay focused on, as much as it is work, the joy that it brings me.”

This joy comes across clearly in Wintour’s performances, and it may be the biggest reason audiences love her. She has such clear respect for the women she pokes fun at, from Midler to Morissette. “What I love about all the divas is that they are people who do not compromise,” she says. “And I think that to make it in this business, even in a small way…it’s so important to stay true to your vision and your beliefs.”

The second-last number in Dear Alanis is “Empathy,” a song about learning to love yourself through someone else. Performing it, Wintour was visibly emotional, wiping her eyes at one point. She thanked Morissette for being there for her, through music, when she was bullied as a kid. She talked about her ongoing struggle with perfectionism and the need to “make it.”

“There’s this part of me that feels like if I can achieve success,” she told the quiet crowd, “all the hurt that came before will disappear.” That isn’t how these industries work, she acknowledged. “But I’m trying to be easier on myself—and I hope you are too.”