Homebound

Between Toronto, Bombay and a new play by Wajdi Mouawad, Adnan Khan explores the ties that bind us.

For almost a decade, I made a habit of visiting India every other year. I visited while I was in school in Toronto, before and after working in South Korea, and on my way back to Canada after two years in Australia.

I didn’t grow up in India. Still, because my family is sort of “from” there—we’re mixed, with roots stretching to Iran, Afghanistan and Punjab—I felt I could make it my home. This was especially true of the city my parents grew up in and around, Bombay (as they taught me to call it, and as I refuse to stop calling it, nourishing the nostalgia of the name).

Then, for five years, I couldn’t afford to make the trip. Simultaneously, the relationships in my life began to crumble. A long-term partnership with a white woman ended, closing a ten-year streak of almost consecutive relationships. My brother was arrested and sentenced for manslaughter, causing a combustion within my immediate family unit. For the first time in a long time, I had no sense of location; I slipped into an in-between state, my inward gaze turning caustic.

I knew these things were normal in the course of a life, but my bewilderment led me to question my foundations; what if my family had never left for the West? What if I stopped dating outside my milieu, and instead, focused on women who were closer to me, culturally and ethnically ? I was desperate to order my life in a way that meant pain could not enter it, and I searched wildly for an answer to the restless clanging I felt.

I had lived in Toronto for most of my life, but I had never called it home—it’s a city I thought, then especially, could never make me happy. Now, I decided to remain disengaged; I relished the in-between zones I was creating, depressing my mind into full-time work at a telecom corporation, understanding that one day I would begin a real life.

When I sold my novel last winter, my first thought was to return to Bombay. I had no commitments there, but now, that seemed perfect; I wanted to rest, recuperate and finish the book. As always, over the last decade, I found myself drawn there like water down a drain.

I discovered the plays of Wajdi Mouawad when I was twenty-two and too young and immature to fully sink into the major themes of his work. Mouawad writes about betrayal, the aggression of lust, and the extreme lengths the displaced will go to find the peace that comes with a sense of home. I was too young, but still, the vitality of his plays shook me and introduced a new kind of vibrant Canadian writing, one that was able to pull the profane and profound together.

Mouawad was born in Lebanon, and his family fled the civil war there when he was a child, eventually settling in Quebec, where he trained to be an actor and grew interested in playwriting. He has since relocated to France and is the current director of Paris’s La Colline theatre. His latest show, Birds of A Kind, premiered in Europe and made its English-language debut at the Stratford Festival in 2019. After reading his work for a decade, I was eager to see it performed.

For Mouawad, the yearning for home is barbed; chasing family secrets and the myths of the past means walking into an abyss. The two main characters in Birds are Wahida and Eitan, Arab and Jewish lovers living in New York; Eitan is German, Wahida American. Wahida is oddly never designated as Muslim, although that is the current that flows through the work.

After the couple’s first meeting, the play pushes to Eitan’s decision to tell his staunchly Zionist parents about his new relationship with the “enemy” while they visit their student son. During this dinner, the play’s philosophical themes are laid out—Eitan’s father, David, is against the union, citing the historical battle between Arabs and Jews as the primary reason. He refuses to meet Wahida.

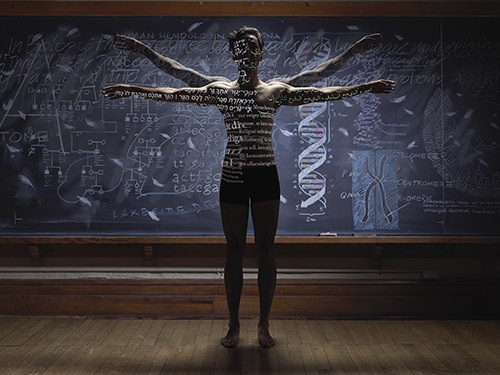

Eitan is a genetic researcher, and in the course of his studies, he learns that there is something hidden about his father’s ethnic identity. The young couple departs to the Middle East, and eventually Israel, so Eitan can confront his grandmother about David’s parentage. After a bombing knocks Eitan into a coma, his panicking parents and grandfather arrive in Israel and David is reunited with a mother he hasn’t seen in decades. The family is forced to face the genetic mystery Eitan is trying to solve.

Many of Mouawad’s plays avoid naming the country or wars they are set in and around, including the one he is best known for, Scorched (most familiar under its French title and film adaptation, Incendies). The technique disorients the viewer, replicating the dislocation his characters move through; as they do not know their origins in full, the viewer also participates in this cloaking, never completely certain of the political and historical vagaries under examination.

Mouawad wisely breaks from this tradition in Birds by naming several historical dates and wars, and concretely setting the action in Israel, directly engaging with the conflict between Israel and Palestine. The play has also been noted for its smooth use of four languages—German, English, Hebrew and Arabic—depending on the situation. Mouawad allows the viewer to bring their own judgments and preconceptions to a piece seeking to address these exact ideas.

That the play made its English-language debut before and during Canada’s election campaign provided a certain kind of harmony to our national conversation. Our politicians struggled to address Quebec’s newly implemented Bill 21, which forbids public-sector employees from wearing or displaying any religious accoutrement, ranging from hijabs to kippahs. Birds, meanwhile, is free from the kind of stiff bureaucratic language of not-offending that cripples these debates before they begin.

Mouawad’s preferred method is to slam his characters into each other as hard as he can and then observe the waste of the fallout. When David, Eitan’s father, speaks about his son’s boundary-crossing relationship, Mouawad allows him to talk ugly, not only to get an intellectual point across, but to inflict, hurt and dominate. By corralling the emotion often stripped from public discourse, Mouawad creates an arena in which ideas can roam freely.

Even grandmothers have free reign to curse and shout in a way that feels normal instead of ostentatious. Despite the aggressive dialogue, Mouawad allows ideas to unpack gently over a performance’s length. He has an especially keen eye for the psychological dread of migration. Displacement is horrific, but so is the search for home that unfolds afterwards, ruining families. Mouawad knows the tension created by moving countries: in order to move forward to a new world, something has to be let go and a new story created that allows the displacement to occur.

Birds shows off Mouawad’s interest in this creation of family narratives: What secrets do we hide from each other? What stories? How does this construct our ideas of ourselves? Mouawad knows that there is no answer to this—that whether migrants are able to move blindly forward or remain obsessed with the past, there is a kind of haunting that accompanies a movement across borders, a longing for home and security that will never fully arrive.

I was in Bombay the year before I read and saw Birds. I had brought girlfriends there before (with the understanding that they were learning something about me, even if no one knew what). I had brought my best friends, anyone who showed the slightest interest; I catalogued favourite bars, restaurants, cafes, pathways. I pledged not to use Google Maps so that I could trace the city myself, asking locals for directions and help with public transport.

To what end, though? I knew I was avoiding seeing my cousins who live in Bombay, even though they were part of my supposed roots there. Bombay could be home because I had trace lineage there—it was where my father’s mother had spent substantial chunks of her life, and while she wasn’t ethnically from the state of Maharashtra, she spoke the state’s languages. People in my family flitted in and out of the city through different generations, for work and leisure. Bombay acted as a beacon for the members who had migrated out: a West-facing port city full of money and pleasure.

It made most sense to reconnect to the city through family members, actual Bombayites, but I was reluctant. I wanted to play-act like I belonged, like there was a way of being in a city and acquiring practical knowledge that would make it home. Maybe I knew that visiting family would bring that sense of belonging under too much scrutiny. My sense of home could only exist privately and would not withstand an external examination.

Blood debts are Mouawad’s concern; war tramples through all of his work, and so does our obligation to our families. We are in permanent bondage to our bloodlines, he seems to say. In Birds, Eitan does not care about Wahida’s “Arabness” or the fact that their families are enemies going generations back. His parents, however, say the couple’s love cannot—and should not—supersede the Jewish and Arab intergenerational conflict. As each character articulates his or her history, each reveals how family can shape political identities. Eitan’s mother, at one point, talks about how her father’s assimilation into secularism led her to her Zionist husband, David, and how her own struggle between father and lover is replicating itself in Eitan and Wahida.

The conflict is confused when the secret of David’s adoption is unravelled. The family learns that David, unbeknownst to him, was an adopted Palestinian baby—he was found by his Jewish father during wartime. This revelation frames the true question of the drama: what is David’s identity? Once his Muslim past is revealed, despite his Zionism, how should we consider his sense of obligations to religion, to family, and to his own beliefs?

Mouawad commits an act of cruelty towards David—he kills him before he finds peace—that’s somewhat common in his work. It’s one of Mouawad’s many nods towards the Greek tragedies. Preventing a peaceful reconciliation for David’s beliefs, Mouawad thrusts control back into the hands of Wahida and Eitan, the carriers of legacy, and asks them to figure it out.

They do and they don’t. Eitan heads back to NYC with a bundle of new ideas about his biology, and Wahida embraces her Arab identity, keen to explore it further. Their relationship, however, is over—doused in love and understanding, accepting that their paths are diverging. By the end of the play, we have no answers to the questions it asks, but we’re asked to accept the wider meanings of home and identity.

Mouawad is a kind of writer that white Canadian grant committees salivate over. His work has always reflected the double bind that Canadian migrants find themselves in. Beholden to our “host” country, the gap between it and us still exists, even as the gap between us and our “home” country widens with each passing moment. That gap never closes; how do I define myself if not “Indian,” as in “Indian-Canadian”?

This logic still prevails. Even the leader of a country that obnoxiously trumpets its “multicultural” values thinks that Brown people are, basically, funny. While Trudeau’s team tried to cloak his blackface blunders as harmless naivety, Bill 21—widely thought to target Quebec’s minority Muslim population—works to enshrine a legacy of discrimination.

Even NDP leader Jagmeet Singh, a turbaned Sikh otherwise proud of his identity, launched campaign ads seeking to mollify frightened Quebecois voters by suggesting he is a human: he has hobbies and a wife. Crucially, in one, he undoes his turban and displays his hair, attempting to dismantle this totem of his otherness. Like Eitan, who struggles to reconcile his love for Wahida with his sense of duty to his parents and to his culture at large, Singh—and all immigrants—are stuck in this forever loop, trying to prove that their new path is not one of loss, that the hyphen between “Indian” and “Canadian” is positive, not an act of destruction. How much work does that hyphen have to do before it is defeated?

In the end, India has never captured the feeling of home I have asked of it. After my first flight landed, when I was twenty, I walked out of the airport to be greeted by soldiers, guns and the odd, sweet smell of burning garbage. The entire month before this first trip I had expected a sudden bloom in my heart when the plane touched down—something would click in place.

No: almost instantly, the sights and sounds made me realize that this was a place I would have to learn to handle. I struggled to follow the rat-tat-tat of Hindi shot all around me; I can’t read the language, I’m illiterate in India; how do these taxis work?

Since then, I’ve visited almost all Indian provinces, major cities and tourism sites. I’ve taken two different white women to the Taj Mahal! It was only Bombay that spoke to me deeply, that answered when I asked. When I was away from it I read every Bombay book I heard of, to ingest the city from afar, even when I was shivering in Toronto.

When my flight landed on this most recent trip it was nighttime. Yellow bulbs illuminated outside the Bombay airport, and the now-familiar smell of burning garbage rolled through the air. I had to call my new landlord for the keys before I made my way over to the apartment. The “STD” (Subscriber Trunk Dialing) stalls—small phone booths, overmanned in the Indian style—were nowhere to be seen. When I’d last been to India four years ago, the booths were ubiquitous, crammed into every nook and corner of public space. I hadn’t worried about a cellphone or SIM card while preparing. I hadn’t thought once of Bombay changing, of becoming unfamiliar.

Frustrated, I wandered around looking for somewhere to make the call. I asked a few taxi drivers, random passengers; no one knew if any still existed. Finally, someone pointed me to a dark corner of the lot where I could see a small booth, its windows blown out, manned by one blind man. I approached him and he handed me an old Nokia brick phone with a few buttons missing. The call cost five rupees. I yelled into the phone and told my landlord that I was here, that I was coming—she promised the apartment was ready. Traveling into the city, I felt astonished that India could change so fast; that I could again feel unmoored despite all my effort.

The rest of the evening was my typical Indian experience: there was a traffic jam, I saw a cow, my apartment was not actually close to ready, I ate a samosa. I thought of Mouawad as I located the chai stall that was to be mine. Mouawad has spoken about feeling like he left a shadow-self behind in Lebanon, one that lingers on in his imagination, a fake “what if” life being built. I like to think that in both lives I would be friends with Josh, a Goan Indian and one of my best friends in Toronto, and that in India we would run stalls side by side, one for tea and one for sweets.

I wonder, in that life, what my imagination would be filled with? Would I dream of the West, like my father did? Would I think of a “better life” in a different way than I do now? This shadow-self plagues all those who leave. Birds has succeeded in articulating the agony of the migrant’s journey, the repetition of the call and response between migrant, the future and the past. Using four languages, three generations and multiple countries, Birds makes clear that the search has no boundaries and may never end.

The play reaches Canadian audiences as Bill 21 marks another step in Canada’s tradition of Islamophobia, following “anti-terrorist” Bill C-51, the Quebec City mosque shooting, and a proposal to install a “barbaric cultural practices” hotline. At the same time, India is moving to strip Muslims of their citizenship in Assam and has ruled in favour of Hindu nationalist interests in a long, bloody dispute over holy sites in the northern city of Ayodhya. Is there room to make a home within any of these nests of hostility?

Mouawad renders the gap between home and self as an unrequited love: does home need you? He asks us what matters more, the blood in our veins or the images we hold close. There is no answer—how could there be?—but the immigrant, despondent and tired, circles, trying to find a way to fix the erasure in their heart.

This most recent trip to India, despite the missing phone stalls, is also the first time I experience no culture shock, either there or when I return to Canada; I slip into Hindi as quickly as I slip into English. The neighbourhood I stay in, Bandra, is populated with English speakers, and I hear the language’s casual trot everywhere I go. Any display of Westernness I thought I had—tattoos, Air Maxes—is matched by my Indian counterparts in this middle-class enclave.

How do we access the past? When I’m waiting for a bus in Bombay, a shopkeeper pops his head out and asks me where I’m from. When I tell him my Abba and Ami are from Bombay, his eyes crank open: “You’re Muslim?” he asks. I’m taken aback by the sudden question. Yes, I say—how did you know? “Because you used the word ‘Abba,’” he replies. He tells me my tattoos mean I won’t get buried in a Muslim graveyard. In the minute-long conversation I’m at once pulled home and pushed out, hyphenated by this gentle, curious stranger.

He tells me what his brother and father do for work, what he hopes for. When we part I say “khuda hafiz,” a Persian phrase my father taught me, often used by Muslim communities in India, a phrase that I usually only ever use with my parents; language that means I’m home.