No Holds Barred

Wrestling is famous for its outrageousness. It takes a special kind of fan to get bored with the mainstream.

It’s Christmas at Foufounes Électriques and a burly, bearded wrestler called Mathieu St-Jacques is thrashing his opponent with a fir tree. Next, he slams his victim down on a glittering sea of fibreglass ornaments which, of course, splinter into a mini-mountain range of skin-piercing jags.

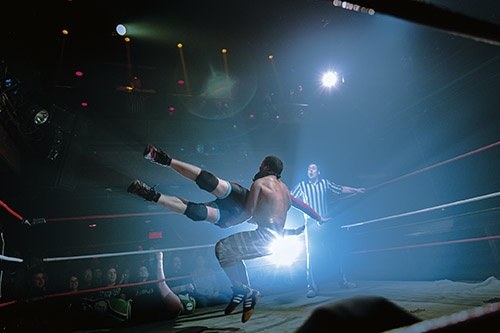

With deliberate sadistic precision, St-Jacques unwraps a gift to reveal a box of thumbtacks, which he liberally sprinkles onto the canvas. The crowd gasps in delighted disbelief at what is about to happen. But in a hoist-by-his-own-petard twist, St-Jacques is the one who finds himself turned into a human pincushion, his opponent, Francis, launching himself from the top rope to add two-hundred-plus pounds of pressure to St-Jacques’s agony.

I’ve been to a couple of these monthly wrestling shows. They’ve had outlandishly costumed competitors performing amazing aerial feats as they make their entrance or take each other down. There was even a wrestler dressed like a seventies porn star whose “magic penis” has the ability to throw his opponents.

Wrestling often relies on elaborate fakery, but tonight the blood looks real. As both wrestlers make their way backstage, I approach the empty ring. Nope, the thumbtacks aren’t rubber mock-ups. The smashed-up ornaments, some of them smeared with blood, really are razor sharp. I’ll admit I feel a little queasy, and perhaps ever so slightly guilty for having just mightily enjoyed this gladiatorial spectacle. Who are these people?

Foufounes is a legendary music bar situated on the slightly seedy edge of the Quartier des Spectacles in downtown Montreal. Opened in 1983, it was named after an art performance by its founding members which involved sticking their naked butts (foufounes) through gutted television sets. It earned its legendary status by hosting formative gigs by the likes of Nirvana, Green Day and the Smashing Pumpkins. (According to the bar’s events organizer Eric Gibeau, Foo Fighters, who also played here in the mid-nineties, have been spotted wearing Foufounes Électriques t-shirts at various gigs around the world. “It was fun to see them still thinking of us like that,” says Gibeau.)

The bar’s punk glory days may be somewhat behind it now. One of its most successful money-spinners is now its weekly Ladies’ Night, perhaps catching the traffic going to and from Le 281, the gogo-boys mecca across the road. Still, though it often reverberates with the sounds of smooth jazz, Dubstep and Top 40 hits these days, Foufs, as it’s affectionately known, continues to host regular punk and metal gigs, its air of transgressive thrills further evident in the sight of the gigantic neon skulls guarding the entrance. The decor still features giant creepy-crawlies, and this winter there was an exhibition of garish, Pop Art-style paintings on the walls that included Mary and Joseph tucking into a Big Mac feast where Baby Jesus should be.

Foufounes has been hosting Battlewar since 2012—a turning point, as it ended up, in this strange scene that pugnaciously distills some of the city’s deepest loves: theatre, circus and live comedy.

Montreal has always been a hub of wrestling. According to Pat Laprade, co-author of the exhaustive history Mad Dogs, Midgets and Screw Jobs: the Untold Story of How Montreal Shaped the World of Wrestling, Montreal was surpassed in wrestling stature only by New York, Chicago, Tokyo and Mexico City.

Laprade also argues that Montreal can be largely credited as the birthplace of the “midget wrestling” phenomenon, but that’s another, less edifying story. And while on the subject of unedifying stories, Montreal is now largely known to wrestling historians as the location for one of the sport’s greatest international scandals, namely the 1997 “Montreal Screwjob” (hence the title of Laprade’s book), which involved Bret Hart losing his WWF title in a secretly planned betrayal at the Molson (now Bell) Centre.

However, a certain uniformity set in in the late eighties, when the US-based WWF (later WWE) took over the territory, putting Quebec’s major promotional organization, Lutte Internationale (known to anglos as “International Wrestling”), out of business. From here on in, large-scale wrestling events in Montreal had mostly outside talent in the ring rather than Quebecers booked by local promoters.

Other local, if smaller, promo organizations persisted. Still others sprang up, including the International Wrestling Syndicate, which began life in 1998 as the Dawson Wrestling Federation, an on-campus project at Dawson College cégep right downtown. One co-founder, known as SeXXXy Eddy, helped introduce improvised weapons into the ring, including chairs and a garbage can. The resulting copious bloodletting appeared to upset the powers that be at Dawson. In the end, the federation went to the mat after Dawson College decided to ban all wrestling on its campus.

What happened between then and now is a quintessentially Montreal story. When you’re a bit too weird to fit into the wider world, the only option that remains is to, well, embrace that fact.

A decadent trio saunters into the ring in their underwear, drinks in hand, during the pre-Christmas Foufounes show. They are arriving from the bar, rather than the locker room, as if to say: “Oh, we’re on now, are we?” They are called Les VIP, and the audience dutifully boos such studied arrogance.

For months now, resident good guy, “Flying” Frank Milano, a heroic figure in a pilot’s jacket, has been resisting the siren call of these louche bad boys. Milano puts up a spirited fight against the three of them, at one point living up to his name by flying over the ropes and taking one of them with him. But the match ends with Milano ignominiously pinned down in a position I can only describe as a flailing beetle.

It’s a shocking turn of events. As part of the challenge, Milano had agreed that, if defeated, he would join the hated VIP faction. Sorrow, anger and pure humiliation drip off him as he’s forced to go over to the dark side, Les VIP hopping about him like grinning demons. The crowd lets out a howl of dismay.

One lady came up to Milano afterwards, recalls Battlewar co-founder James McGee; many of the performers mingle with the fans post-show. “And she was like, ‘Why does this have to happen!?’” McGee demonstrates the solicitous concern with which Milano broke the bad news about Les VIP to this elderly and ultra-loyal Battlewar fan: “I’m sorry; they cheated.” And, he recalls, “She’s believing it! She’s crying!” I’d swear that as McGee remembers her heartache—all over a pre-scripted scenario—his eyes are glistening too.

“Montreal’s always been a hotbed for wrestling,” he says. “Montreal loves live entertainment.” As a lifelong sport-a-phobe myself, I was only lured to the Battlewar arena by McGee, one of my favorite Montreal comedy performers. The artistic director for, and a frequent performer at, Montreal Improv, McGee has also created some eye-wateringly funny one-man shows in Montreal. He was a DJ-in-Hell in SCUM FM and did a children’s TV parody, Le Merveilleux and Marvellous World de Bonhomme Caramel. One time in 2016, when I was interviewing McGee, he happened to mention that he was also a professional wrestler and had co-founded some monthly wrestling event.

McGee truly has a comedian’s mien, with toothsomely ingenuous and malleable features peeping through his beard, he looks, in performance, like a Dostoyevskian holy fool about to step on a banana peel. But during the early 2000s, McGee trained seriously at the International Wrestling Syndicate, the successor of Dawson’s league.

Despite getting kicked off campus, the league had gone big, adopting a new name, sparking a whole new independent scene in Montreal. But a few years later, in the early 2010s, the syndicate went on hiatus and there was a downturn. This meant McGee had to leave town if he wanted to keep wrestling—and to wrestle for audiences he wasn’t used to. “I barely performed in Montreal anymore,” says McGee. “I would perform for companies that ran out of Ottawa or Quebec City, or one-off events in the US.”

As a child, growing up in the Laurentians town of Prévost, McGee only had two interests, he says: Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and pro wrestling. He spent much of his time in his backyard making action figures wrestle and writing storylines for them. And he was just as tied into the local scene. “When my family got a computer in, like, ’99, I discovered oh, there’s other wrestling that isn’t just limited to the WWF and, gosh, there are companies here in Montreal,” he recalls.

Luckily, one of McGee’s childhood friends also loved wrestling, so together the two grew up, trained and weathered the wrestling downturn. Finally, in 2012, the friends decided to start something exactly to their own tastes, without relying on anyone else. “Wouldn’t it be great,” McGee recalls asking, “if something fun existed in Montreal again?”

These days, McGee’s appearances at Battlewar draw more on his skills as an improviser than as a grappler. His character is called Twiggy, and a few years ago, Twiggy was a plucky little underdog adored by the crowd—in wrestling parlance, as Laprade explained to me, good guys are “babyfaces.” Since then McGee has gone from lovable babyface to despicable “heel,” i.e. bad guy.

“I’m what we call in the wrestling world a ‘chickenshit villain,’ the type who causes trouble and runs away,” McGee says. He describes his alter-ego as “wormy,” a quality he tries to conjure up by wearing seedy-looking cardigans. What wrestling he performs at Battlewar seems to happen by accident, such as when he’s set upon by fellow heels the Salty Bullies. Sometimes he even brings in members of his Montreal Improv colleagues to build the plot, like when Twiggy, as part of his pre-event schtick, posted a wholesome family Christmas video on Facebook to shamelessly win over the crowd. (In keeping with the knowing absurdity, his “son” and “daughter” in the video were just a couple of years younger than himself.)

There’s something of the traditional pantomime in the way the performers encourage cheers, boos and cat-calls from the audience, many of whom are repeat customers. The audience, you feel, are fully aware that they’re part of the performance too, and are hell-bent on matching the crazed action inside the ring with a frenzied reaction outside it.

Defining who is the good guy, and who the bad guy, is part of the ritual. “Usually if you’re a really good ‘good guy,’ you can be a really great bad guy, because you’re betraying the audience,” says McGee. “So month after month, I’d kind of sour the soup a little bit. I’d think: what’s the best way I could become a villain?”

Whereas Les VIP stir people up with their insufferable smugness, one way Twiggy did the same was to become an enemy to inclusivity at Battlewar, threatening to ban female competitors because, as Twiggy loftily put it, the audience wasn’t ready for it. “I’d… blame the audience—‘I don’t think you’re giving this the encouragement it deserves, so maybe next month.’”

Several women wrestlers have, in fact, performed at Battlewar, many of them drawn from the Montreal-based pro wrestling company Femmes Fatales (for which Laprade is co-promoter). And if we can make the case that Battlewar’s flamboyant stagecraft and fictional storylines make it an outlier of the theatre scene as well as the athletic one, we might also point out that women directors currently outnumber men in Montreal’s major theatres. Small wonder that Twiggy’s deliberately condescending provocations riled up the local crowd.

That was the moment, McGee recalls, that his character really made the babyface-to-heel transition, with a cacophony of boos meeting his decision, along with chants of “Fuck you, Twiggy!” and “Twiggy sucks!”

“I think we all know it’s a show,” McGee says. The Battlewar championship title belts that the competitors seem to expend so much sweat, tears and torn ligaments to win are impressive: thick black belts decorated with gleaming crests featuring a map of the globe and “Battlewar Wrestling Champion” spelled out in red. But they too, McGee readily volunteers, are “just props. It’s just tin on leather.” Just as the outcome of every single match is cooked up by McGee and his partner in their office.

Yet people still get so caught up in it, they end up crying. It reminds me, I tell McGee, of viewers of British soap Coronation Street sending hate mail and condolence cards to characters, or signing petitions on behalf of incarcerated ones. “Well, Coronation Street was always on in my house when I was growing up,” McGee smiles, dreamily recalling his childhood in Prévost. “My family watched it religiously. So to be compared to Coronation Street, that’s a big compliment for me.”

Battlewar is now part of a longer roll call of independent Montreal wrestling companies, as the scene has tenaciously regrouped. These include La Descente du coude (Elbow Drop), which operates in the East End, and the Federation de Lutte Québécoise, which, in a perhaps mischievously provocative echo of Quebec’s infamous paramilitary group, goes by the acronym FLQ.

This renewal hasn’t just brought back local wrestling but has sent a new wave of talent to the bigger industry—an idiosyncratic, Montreal kind of talent. Laprade points to the success of El Generico, aka Sami Zayn, one of whose last matches on the indie scene was at Battlewar before he was signed up for the WWE. He’s on the small side for a wrestler, says Laprade. “A few years ago, somebody with that type of shape would never have got into the WWE league. They were looking for guys around six-foot-three, 230 pounds. But people like Sami really connected with the crowd.”

Another Battlewar veteran, Kevin Owens (heavy for a wrestler: “260 pounds, big belly” as Laprade describes him) also made it onto the WWE’s books. That kind of hire, Laprade says, “opened the eyes of many fans to the independent scene in Quebec. They see these guys and think: oh, you know what? I might go to my local promotion and see future WWE superstars before everybody else.”

Battlewar has ventured into other venues with slightly less of an anything-goes spirit, including Le Belmont on St. Laurent Boulevard and Mainline Theatre a few blocks south, but McGee sees Foufounes Électriques as its natural home. The upstairs space is more used to the screeching decibels of live bands with names like Rotting Christ and Abysmal Dawn. Battlewar fits right in; there’s even a mosh pit of sorts, as wrestlers are frequently hurled out of the ring and into the front rows.

Given that Foufs is immediately east of St. Laurent, I wonder aloud if the anglo-franco divide, of which that boulevard is traditionally a symbol, gets factored into the drama. The audience, mostly twenty-to-thirty-somethings, seems to be predominantly francophone.

“Sometimes it’s an opportunity to be villainous,” says McGee. “For instance, I’d come out, maybe around holidays, and say ‘I just want to wish you all a Merry Christmas. And for our French fans...’ I’d take out a little note and say ‘Joyeux Noël’ in the worst possible way,” mispronouncing it, “and just crumple up the paper and throw it aside. Little things like that work.”