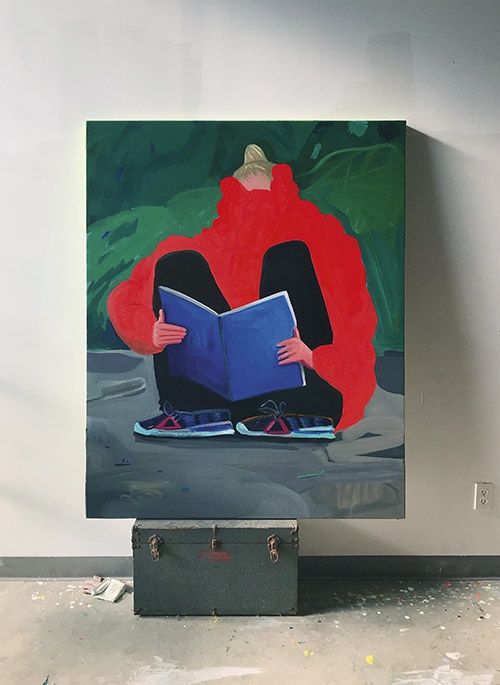

"Trying to read the blue book (2020)" by Kate O'Connor. From the series "Shelter in Place."

"Trying to read the blue book (2020)" by Kate O'Connor. From the series "Shelter in Place."

Metaphorically Speaking

Apocalyptic novels used to be fun, Kevin Chong knows, but writers of the future will have to get their own literary devices.

Covid-19 has been a sky-swallowing shit cloud. And yet for me it has also been a promotional boon! Folks have noticed how my 2018 novel The Plague is also about infectious disease and quarantine.

Here’s how I became accidentally prescient: in my novel, Vancouver is quarantined after an outbreak of the bubonic plague. As disease sets in, the characters meet as usual in a yuppie neighbourhood that I imagined built if the city’s poorest area, the Downtown Eastside, were bulldozed after the opioid epidemic had decimated its population. Where needle exchanges and support services now stand, I imagined gastropubs and luxury condos—or even more than there already are. But eventually, the plague overruns the entire city.

The plague symbolizes what happens to a problem when it’s ignored or used to weed out the “undesirables”—it returns with exponential force. I wanted to highlight inequality and the experiences of marginalized people by using the most outlandish, impossible scenario I could imagine. So much for that.

Five weeks into being housebound in Vancouver, I’ve completed a phone interview while hoofing my daily walk around the block, a radio spot over the phone while trying to stifle a lingering cough (not Covid-19—no fever, no lack of smell, et cetera), and am booked for a podcast. And completely random people—four, tops—have taken to posting about my novel on social media alongside pictures of their loaves of sourdough and unpeopled trail hikes. So, for me, this period of death and fear has been . . . bittersweet.

I can’t blame readers searching for books that play-act what we’re going through now, whether it’s Albert Camus’s classic La Peste—the inspiration for my own work—or pandemic novels like Ling Ma’s Severance and Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven. Or even a tale of self-medicated self-isolation like Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation. Books like these allow people to bat around some of their own feelings during this time. And yet I don’t count myself as part of this group of readers. Not when metaphor gets so eerily and identically eclipsed by reality.

If you want an example of another writer whose work aligned with current events, look no further than Don DeLillo, who came to prominence in the 1970s and 1980s. His 1988 novel Libra examined the John F. Kennedy killing through the eyes of Kennedy’s alleged assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald. A few years later, in his 1991 novel Mao II, DeLillo described a reclusive novelist who travels to Lebanon to try to secure the freedom of a poet held hostage there.

DeLillo was suggesting that terrorists were beginning to shape the public’s understanding of the world, and that this kind of influence had previously been reserved for writers. “News of political terror was beginning to move into a narrative that used to be the stronghold of the novelist,” he once noted. “Not long ago, a novelist could believe he could have an effect on our consciousness of terror.”

No novel, past or present, could have the effect that the September 11 attacks had on our collective psyche. But in the aftermath of 9/11, readers noted the “prescience” of the cover image of DeLillo’s 1997 doorstopper Underworld. The image features the World Trade Center buildings in the backdrop. After 9/11, the bird in the cover’s foreground suddenly resembled one of the planes that crashed into them. Readers who discovered DeLillo’s work in the aftermath of the so-called War on Terror might have found it retroactively obscene and unintentionally opportunistic. They would have also missed his point.

As with DeLillo, readers can now fact-check my book in real-time. That won’t go well for me. It wasn’t meant to be realistic, and I certainly didn’t consult any epidemiologists. And I know if I were to write my novel now, I would have to add the work-from-home chapter, the grocery store trip that feels like a foray into Zombieland. All of which sounds better than another Zoom meeting.

Thus far, I have made no attempt to predict the future in the novel I’m currently writing in the abundance of free time I’ve had foisted on me. Yes, I’m writing a novel. And no, it’s not a very unique quarantine activity. I snickered at a recent Guardian headline, “Finally working on that novel as you self-isolate? You’re not alone,” because the second sentence can be read as an affirmation. Put down that laptop! Life is still worth living.

I won’t tell you what my book’s about; it’s too early to discuss. But will you pause with me, dear reader, to think about what novels other folks might be writing? I would hazard that some hacks are already fictionalizing their quarantine experiences, and I would rather swallow glass than be their beta readers.

In my university writing classes, in response to pre-pandemic assignments, a few students recently submitted pieces that deal with Covid-19 and quarantine, but I’ve treated them as coping mechanisms. They’re writing the only things they can in the moment, like a lot of the new writing published during the pandemic I’ve seen recently. Other students have ghosted on assignments altogether, and I can’t blame them for responding to a once-in-a-lifetime disaster with silence. If only to avoid the new tropes and buzzwords: social distancing, self-isolation, Quarantini.

Better leave it to our grandkids to romanticize this period the way today’s Gen Xers still set their novels during World War II. Future generations might use it as an opportunity to understand why their elders were such damaged people, to understand what went wrong in their own lives. That’s how experience is transmuted in fiction. You use one thing to talk about another. Fiction works best when it’s addressing things subtly, rather than head-on. Think of a novel as a three-hundred-page subtweet.

Let’s step back from the distant future and our grandkids’ creative ambitions, and spare a thought for today’s writers and readers. Let’s think about how the quarantine will serve as subtext for the works of fiction that will appear in the next three to seven years. People will be trying to process this, and the most compelling work will do so by talking about everything but the pandemic. What are fiction writers going to swap out for quarantine and the fear of contamination?

Will we see imaginative recreations of the Siege of Stalingrad or stories about viking explorers searching for a way home? Will more writers tack toward fantasy and science fiction? Or will they be writing stories of lovers sitting at barstools, or kids at pools?

And here’s my biggest, more serious question: how will we represent the trauma, the build-up of angst, ennui, depression, fractiousness, domestic dysfunction, that this quarantine has stoked? In some ways the readers of tomorrow will be primed for works that help them process this collective pain.

Or not. After all, the bestselling book in the US in the years after 9/11 was The Da Vinci Code with its pure escapism. The problem with waiting to process pain is that it becomes easy to pretend it never happened and seek any diversion in its place.

Writers, however, write to be absorbed in worlds of our own making, preoccupied with the struggles of imaginary people. In these days that are as same-same and uniform as a pallet of two-by-fours, we must keep on hewing our own textures and spaces within ourselves.