Labour of Love

Politicians have whittled down public health care for years. While caring for his dad, Ryan David Allen learned who picks up the slack.

In the spring of 2013, my father, a long-time alcoholic, earned his first full year of sobriety in over a decade. To celebrate, he drank again.

I only knew because I had been trying to call him and couldn’t get through. He lived alone in Halifax and normally couldn’t go more than a few hours without calling me to speak of something inconsequential—so any time he wasn’t answering the phone, I knew that something consequential had occurred. And in the life of my father, a thrice-divorced, ex-chemist, multi-hyphenate manic of a man with a penchant for all-nighters and abandoning vehicles on the side of the road, I knew there was only one thing that could suppress his vitality: himself, drunk.

After two or three days of not being able to reach him, I’d usually get the hint and stop trying altogether. By this time, I was twenty-four. I had learned not to engage with him when he was drinking, for both our sakes. My steady closeness to his tumultuous recovery during my formative years gave me something of an aversion to his relapses in early adulthood. Anything I said when I was upset would only add to his list of personal wrongs that made drinking seem right. I’d keep my distance, and he’d keep his drink.

That spring, after a week of zero contact—his binges were lengthy—I looked at my phone during a band practice and saw a long row of missed calls from my father. Worried, I called him back, and he answered immediately. His voice was shaky and had its often-buried Northern Irish accent, as it always did when he’d been drinking. Over the course of a very strained conversation, he confessed that he needed my help. “I’m done now,” he said.

I knew what he meant. Now that the journey into the depths of his sadness was complete, he had to begin the slow, painful crawl back to sobriety. Within a day, the withdrawal symptoms would kick in. And that also meant something else. Lacking anyone else in his life that he could rely on during withdrawal, I would be stepping in to help him.

Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome is the name for a cluster of symptoms that arise when a heavy drinker stops—or sharply reduces—their acute alcohol intake. An acute drinker enters the withdrawal phase about six hours after their peak level of intoxication. Initial symptoms include tremors, anxiety, nausea and restlessness. For those who are only mildly alcohol-dependent, these symptoms may be the only ones they experience and will subside without any treatment in mere days.

Approximately 10 percent of patients, however, experience low-grade fever, sweats, tremors and rapid breathing. The most severe withdrawals may even bring seizures and delirium tremens, often called “DTs.” Author Charles Jackson, in his masterful, autobiographical tale of addiction, The Lost Weekend, called delirium tremens “the disease of the night.” DTs typically occur within one to four days after the onset of alcohol withdrawal. Aside from causing sweating, fever and tremors, some may even hallucinate, or “see pink elephants,” as was the popular euphemism for alcohol-induced hallucinations in the nineteenth and early twentieth century.

While anyone with a compromised immune system may be at risk during alcohol withdrawals, seizures and DTs coupled with any of the other symptoms can be fatal. The mortality rate among those who exhibit Stage Three symptoms is 5 percent to 25 percent. Contrary to popular conception, withdrawal symptoms for those deeply addicted to alcohol are much more severe than withdrawal symptoms from other drugs—even those drugs whose use is more vilified by society, like heroin or OxyContin. That’s why seeking treatment, typically through withdrawal management programs or inpatient detox wards of hospitals, is crucial. “Withdrawal management” refers to the medical and psychological processes administered to ease the process of withdrawal. Patients are monitored closely by medical personnel and, in some cases, may be given medications, often ones from the benzodiazepine family.

There is more to the author Charles Jackson’s quote about delirium tremens. “Delirium was a disease of the night, yes,” he begins, “but also—oh worse!—delirium never came while drinking. Only after you had stopped.” Things got messy for my father when he stopped drinking his whiskey and beer; they were arguably even messier than when he drank. Often, my father would turn to Listerine mouthwash. Listerine, for the uninitiated, has an alcohol content of 26.9 percent, almost quintuple the percentage of most domestic beer brands. He drank it not out of preference, but solely because it was the only thing available—or, other times, simply because he could not stop drinking for fear of withdrawals. On the occasion when he called me, he’d finally run out of both alcohol and mouthwash.

In moments like this, it was crucial that he be admitted to a public detox facility. Seizures, DTs, dehydration were as certain as a hangover for my father at this stage of his alcoholism. Given his advanced age of sixty-eight, he was also at risk for cardiovascular complications. Many times in the past, his heart had stopped beating, though thankfully only when he was already under medical supervision.

This time, however, the hospital didn’t have a single bed available. They told him to call back the next day, and the next day, and so on. It was after a few days of calling the detox facility that he finally called me.

In 2016, Halifax, with its population of over 400,000, only had sixteen publicly funded detox beds for adults. Some people were waiting three to four weeks to receive a bed and treatment. Chris Parsons, the provincial coordinator for the advocacy group the Nova Scotia Health Coalition, calls this “woefully inadequate.” For many people trying to get sober, he says, “a five-day wait period is the difference between them deciding that day that they want to turn their life around, or relapsing.”

Across Canada, each year seems to bring more cuts to public addiction treatment programs. In Montreal, the city’s only free public detox and addiction treatment centre removed ten of its twenty-eight remaining beds in 2018. In Ontario, the Ford government cut addiction programs last year for people on social assistance. In decisions about where to save on health care, Parsons says, certain services are privileged over others. “Things like addictions treatments, mental health treatment, ensuring that you have culturally competent care for immigrant communities, and reproductive health care are seen as ‘extras,’” he says. Over the course of my life, and my dad’s many lives, I know people often saw his addiction as a matter best dealt with privately.

Recently, of course, everyone has suddenly begun talking about the holes in our public health system, because of Covid-19. As the virus spreads through nursing homes and cities, as the most vulnerable have gotten sick and died, it’s become nearly impossible to avoid acknowledging the strip-mining of the public health sector, just how thinly our systems are spread after decades of ruthless government austerity.

Canada may stand as a shining example of improved health care to our neighbours in America, for example, but the bed shortages we’re worrying about during the pandemic are just magnified, not new. The world’s high-income countries have an average of around four to five beds per thousand people, according to data from global organizations like the WHO and the OECD. China, ground zero for the virus, has 4.3 beds per thousand people. South Korea has 12.3 and France has six. Two of the countries hardest hit by Covid-19, Italy and the US, have 3.2 and 2.8, respectively.

Yet Canada only has 2.5 hospital beds per thousand people; we are consistently at or near the bottom of the list of comparable countries. Hospital-bed density in Canada has been on a steady decline since 1976, when at the high point there were 6.92 beds per thousand people. Since then, populations have grown, but hospital funding hasn’t increased accordingly. The situation is most dire in regions with the greatest population density, such as Ontario, which has retained the same number of hospital beds since 1999, despite seeing a 27 percent population increase over two decades. Of course, bed density—how many people can fit inside a hospital—doesn’t necessarily tell you how many people can be treated at any given time. That also depends on the availability of nurses, doctors and other resources.

Before the pandemic, Canadian hospitals were already long familiar with “hallway medicine,” where hospital beds are placed everywhere from hallways to conference rooms to alleviate chronic overcapacity. In Ontario, where overcrowding is most severe, forty out of 169 acute care hospital sites averaged 100 percent capacity or higher during the six months analyzed in 2019, while about half of those hospitals were beyond 100 percent capacity for more than thirty days. Canada was ill-prepared for even the slightest uptick in hospitalizations, let alone a full-blown pandemic.

The results have quickly become clear. In March, Ontario’s health minister asked the province’s hospitals to scale down elective surgeries, while BC ordered hospitals to postpone all non-urgent surgeries. Even though BC authorities reversed this order less than two months later, they said it would take two years to clear the backlog the delay had created. In New Brunswick, the province’s only abortion clinic is on the brink of closure and inaccessible to anyone unable to travel to the city of Fredericton. Those who cannot commute to Fredericton have no choice but to go to overcrowded hospitals, putting themselves and their loved ones at risk. The hospital in Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, advised pregnant women to call ahead before arriving at the hospital in labour due to a shortage of anesthesiologists. Canada has long been whittling health care of its essential services, but the pandemic has replaced the whittling knife with an axe.

It’s also become increasingly obvious who’s picking up the slack. Also in March, Global News reported the Royal Ottawa Mental Health Centre’s substance use and concurrent disorders program discharged its patients to friends and family—or at least people who had friends and family went to them—on account of the pandemic. Meanwhile, some doctors, nurses and others on the front line were told to reuse scarce single-use masks, endangering themselves, their families and other patients. Even employees and volunteers in Quebec’s long-term care homes, the epicentre of the outbreak, continued working without sufficient personal protective equipment. By April, two patient-attendants in these homes had died of complications related to Covid-19.

The circumstances we find ourselves in due to the pandemic may be new, but the broader conditions are definitely not. Our universal health-care system has long required regular people, both patients and those left to care for them, to make sacrifices and overextend themselves. In 2019, in another example of the already-burdened becoming burdened by the government’s problems, concerned residents of Kentville, Nova Scotia initiated a crowdfunding campaign to raise money for more hospital beds at the regional hospital in the Annapolis Valley.

People fundraise or play the role of at-home caregiver out of a sense of obligation to their community or those they love, thinking that if they don’t, no one else will. Sure, trimming costs in our health-care system might save money. But there are untold costs to the people who volunteer, reluctantly or not, to fill the gaps that are left.

Authorities have always failed to account for this toll. People like me, who are left to care for someone at home, do so without adequate training, resources or support. We do it simply because we can’t not—which is what the system banks on, now more than ever. Again and again, the health-care system exploits the sense of obligation we have to one another. Now the whole country must reckon with this fact, not just those on the margins.

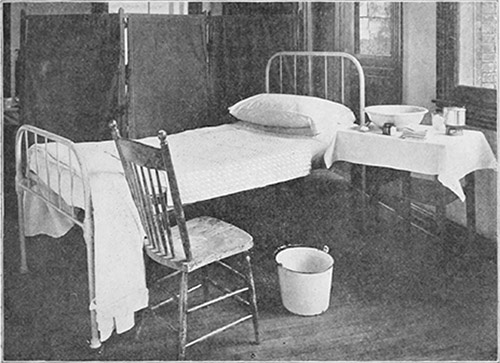

Dad lived in a semi-basement one-bedroom apartment within Joseph Howe Manor on Victoria Road, a metro housing unit for senior citizens that cost him a third of his monthly income, whatever that might be each month. As a kid, I lived with him during summers, holidays and weekends, sleeping in the creases of his foldout couch. Mostly I opted to stay with older friends so as to avoid him while he binged. The walls of his room were yellow from indoor smoking. His bedroom was filled with his old computer parts, an old mattress he’d never discarded, and the same tiled floor you’d find in hospitals.

When I walked in that day he called for help, his television was set to a low companionable volume in the living room, and he was curled on the adjacent bedroom’s lumpy, sweat-soiled twin mattress with a single sheet over his body. He tried to get out of bed, but he couldn’t. I gave him an Ensure protein shake, which he’d requested, and put two cases into his refrigerator.

Substance abuse wreaks havoc on addicts and everyone in their vicinity, and few have the tools to help. Many take the approach that I took for years—one guided first by my self-preservation, but also by the idea that an addict should truly reckon with the consequences of their actions. This is known both colloquially and officially as “tough love.”

The tough-love method is practiced by many, even if they don’t know its origins. American author Maia Szalavitz, in her book on addiction, writes that the concept of tough love was fine-tuned in Al-Anon—different from Alcoholics Anonymous, this is a family support group founded by the wife of the man who co-founded AA, Bill Wilson. Later came Phyllis York’s bestselling 1982 book Toughlove, which urged readers not to bail out their children if they were arrested, and to cut off contact if the children backslid into destructive behaviours. Many tough-love adherents went on to become prominent in other treatment organizations, advocating for more stringent drug laws and draconian treatment programs rooted in Synanon, the infamous and now-defunct rehabilitation centre-turned-cult. Synanon’s founder aptly distinguished his philosophy from AA-based Twelve Step programs by saying: “Alcoholics Anonymous is based on love, we are based on hate, hate works better.”

Though I’d never officially been schooled in the ways of tough love, I arrived at a similar frame of mind in my teens. After an adolescence of getting caught in the crosshairs of his addiction, and having long denied myself any emotional support for fear of outing his problems to the rest of my family, I had no support left to offer him. Maybe I thought that, in denying him my compassion as a form of punishment, he’d respond. Or maybe I thought I had finally earned the right to express the anger I’d long withheld, regardless of how it made him feel. Whatever my reasons, none of it made me feel better, and none of it helped him.

Surveying my dad’s apartment that day, I saw empty cans strewn throughout the living room as well as several empty bottles of Listerine. I wanted him to know that I wasn’t there to tell him about how he’d ruined my childhood, so I cleaned his apartment as best as I could, though, unfortunately, my standards for cleanliness back then didn’t go much higher than his. Regardless, I’m sure he saw me, out of the corner of his eye, cluelessly trying to sweep dust and bottle caps into a chip bag, felt my love for him, and understood that we’re all only ever trying.

I knew, upon discovering the grocery bag that he’d gotten sick in, that this binge was different. If not for him, then at least for me. He was neither drunk or sober, I realized. Instead, he was caught in the in-between: the throes of withdrawals. I’d gotten a sense that his binges and withdrawals took a greater toll on him than they used to on account of his age and compounding health problems, despite his doctors having always said he was healthy. But because of the self-imposed distance between us, that was the first time I ever fully realized the severity of the withdrawals.

I left his tiny apartment and asked him to please call if he needed anything else. I went back to my friend’s recording studio to get ready for the summer tour I was only days from embarking on. The next day, he called me again. With an even shakier voice, he asked if I could go to a pharmacy and buy him Dramamine, or as most people know it, Gravol. Dramamine helped curb his nausea, vomiting and feelings of motion sickness. Dramamine was incredibly affordable, even to a passively employed person like me, so I ventured out again to buy some and walked to his apartment.

When I arrived he was on the couch, facing the back cushion, as though he were giving his companionable television set the silent treatment. He immediately took three of the pills with a glass of water. “Hope I don’t just throw these up,” he said. I hoped so too, but more than anything I hoped he’d finally be admitted to detox.

As the days passed, I became increasingly worried that that wouldn’t happen: that my dad might not get in, and would just be left alone after I went away. I was worried that he was having seizures when I wasn’t there. I was worried his heart might stop. I was worried I might be away when he died. I had a laundry list of worries, and his actual laundry to worry about on top of it.

When he called to ask if I could find him some Valium to cope with the withdrawals, I was a day away from leaving town. I asked every person I knew if they had any Xanax, Valium, or other similar drugs. Every person I asked, though, from the overachievers with secret predilections for prescriptions to the underachievers interested in recreating the rituals of their rock idols, somehow did not have a single drug from the benzodiazepine family in their possession. People could stumble onto drugs in a bathroom lineup and I couldn’t even shake down the friend who’d just spent a semester in Berlin—Berlin!—for a single pill. But aside from failing my generation, I felt like I’d failed my father.

I visited him twice more over the next thirty-six hours. My older sister, who lives in Alberta, also called him regularly over those days. The only other thing left to do was wait, and hope a detox bed would finally become available.

What I wished for at the time was that some guardian angel would swoop down from the heavens with a handful of narcotics to aid my father. But what would have been ideal would be for him to get adequate care from trained professionals, and not just me—an ill-equipped barely-adult who, at the time of publication, still can’t even drive.

This spring, upon first hearing the news of the discharged Royal Ottawa patients, I couldn’t stop thinking about the families or loved ones they returned home to. My father wrestled with the guilt and shame of being nursed through withdrawals by his son—and before me, others—who also played the role of therapist. That guilt and shame only exacerbated the depressive thought patterns that would precipitate future relapses. If there’d been others witness to it, say younger children, I could imagine all they’d be exposed to—the mood swings, the howling sickness of withdrawal, relapsing and its attendant messes—at such a crucial stage in their development. Imagine, then, the trauma of having witnessed such things, and that trauma rippling beyond that child’s youth and into adulthood, into the lives of others, and the lives of others, ad infinitum.

But think about the patients, too. When the onus is thrust onto someone’s family and community, it would be nice to think that that community responds with finesse. But they’d need resources for that, whether outpatient treatment programs, safe injection sites, methadone clinics, cognitive behavioral therapy or medications like naltrexone.

Of course, some communities can come up with their own resources, on a much bigger scale. As less funding is allocated to free and publicly funded treatment programs, for-profit centres have become prominent in Nova Scotia and elsewhere. The treatment and recovery program at Ledgehill Treatment Center in Nova Scotia’s Annapolis County costs $25,000 for forty-two days.

What I find most reprehensible are the cases—more common than you’d think—where private treatment centres have built their programming around the open-source code of the Twelve Steps. These centres rely largely on what one can find for free at a local AA meeting. And though AA might have the answers for some, it does not have the answers for everyone.

Many people, when they can’t afford these costs, still find ways to pay. An individual or their family may sell belongings, take out mortgages, liquidate their savings or sink into unfathomable debt. Families in this situation can quickly spiral out of control, creating the sort of environment that makes it even more difficult to thrive in the future. Addictions can worsen and lives can be lost. “Say you get out of rehab, and it turns out your brother’s sold his truck to pay for your treatment,” Chris Parsons says. “That guilt weighs on you and impacts your ability to maintain your sobriety.”

In any case, one needs to be part of a community or family for anything like that to occur. As Stephen Thomas wrote for Hazlitt in his excellent piece “The Legion Lonely,” people—men especially—are susceptible to the kind of existence that prevents them from latching onto any kind of real-life community. Though my father did have some friends and a support network through Alcoholics Anonymous, they knew that there was no talking with him when he was drunk, so he lost that connection in those moments, only furthering his isolation.

Beyond that, even if he’d had a friend who could have spent a week beside him while he endured his withdrawal, there’s no telling what would happen to that friend’s job. According to Canada’s federal labour laws, employees are only entitled to compassionate care leave—unpaid—if they are looking after someone they can justify is “like family.” Thankfully, I lived in the same city as my dad. If nothing else, I at least had the time to visit him.

And then, the week of his relapse in 2013—the morning I left for New York—my dad finally received word that there was a bed for him in the detox ward. In total, he had waited five days, longer than most waits he’d ever had to endure. By that point, he’d already passed through much of the disease’s long night, as I thought of it, but the hospital would see to it that he received the care needed to get through the rest.

In a Montreal Gazette opinion piece from April, Susan Mintzberg, a PhD candidate in social work at McGill University, examined the role of families in senior-care facilities during the pandemic. Many people have now come to recognize how crucial family support is for people living in long-term care homes, whether they simply visit or help in other ways. “Let the families back in,” Mintzberg wrote. “They have experience, come at no extra cost, are available immediately and are desperate to help.” Though family members may not have professional training, she argues, they play an important role in “allowing our health-care system to remain afloat.” (In the end, in May, Quebec did allow and even urged family members to return to help with relatives in care homes.)

I agree; the importance of healthy family bonds for the elderly or sick can’t be overstated. But this love and effort can’t fill the bigger gaps, and we can’t expect them to. At best, this is a Band-Aid on problems in dire need of fixing. At worst, it exposes both the caregiver and the person they’re caring for to deep harm, psychological and physical. There’s a reason that the Canadian Medical Association advises doctors against treating loved ones, as quality care demands professional objectivity. And while some residents may have loving families who can help care for them, some don’t, or their families may not be able to visit very often. What’s paramount is the quality of facilities and the welfare of their paid employees.

On April 17, not long after that editorial appeared, Quebec’s premier admitted that raises for long-term care were long overdue and that facilities were deteriorating. Given the conditions of these facilities, and the strain on workers, how much can family visits do to really improve the situation overall? How long until the staff of Quebec’s government-run senior residences go on strike, as staff from ten of the province’s private seniors’ residences already did in 2019, before the pandemic? How long until families are expected to carry an even heavier burden?

There are signs that, in the pandemic, governments are beginning to recognize the value that family members and loved ones play in caring for those close to them. People with children can now receive as much as $450 per week for up to fifteen weeks while they take care of a loved one. But there are costs to this, too. Financial benefits like these and the $2,000-a-month Canadian Emergency Response Benefit, which some have heralded as an unintended experiment in Universal Basic Income, could just undercut existing social programs. Worse, they could create another excuse to avoid properly funding the system, which will further entrench those who need assistance the most. Two thousand dollars a month is a paltry sum when one also has to pay for health care and other social services. In my experience, the issue wasn’t that I was not being paid to care for my dad. The issue was that there was no one else in sight to do so.

Had he been left alone during the five days he waited for a bed, without calming calls from my sister or visits from me, I believe my dad still would have managed to survive the withdrawal; Dad was perhaps too resilient for his own good. What he wouldn’t have been able to endure, I’m sure, was the path of sobriety that came afterwards. In the days after returning from detox, he was emptied of all but shame and fatigue, left to play catch-up on the several weeks of time he’d lost during the bender and the subsequent medically-assisted un-bending.

For the best start possible, he needed assurance from those around him that his relapse hadn’t resulted in his dismissal. Our being there in the midst of his binge and afterwards gave him that assurance. Upon his return home, he told me that he’d never felt so cared for during a relapse, despite the fact that my sister and I were able only to provide the most basic comforts.

Like most stories of recovery, it didn’t necessarily end there. Even after the relapse in question, my father relapsed once or twice more before he passed away from cancer. However belatedly, I finally came to understand that this would perhaps just be the rhythm of his condition. All I could do was treat him with the love and compassion he deserved, sober or not.

I was lucky that I came to terms with this fact. I’m lucky I didn’t make a rash decision to cut my dad out of my life for good. For many, though, the only drug-recovery narrative they know is the most draconian one, the one that doesn’t leave room for the bumpier, endless road of recovery. In this punitive narrative, those who fail to abstain are less deserving of support and encouragement, even from their loved ones. Relapsing is not a moral failure, or any sort of failure.

What is a failure, however, is how those in charge of funding and running our hospitals perpetuate this judgmental approach while also failing to provide adequate care.

But they ask too much of all of us, whether addiction is involved or not: too much of our love, our capacity for guilt, our sense of right and wrong.

Sometimes people need to keep some space, protect themselves in some way, from the sick, whether neighbours, friends or family. They shouldn’t be forced to choose whether they look out for themselves or look out for someone else. No unprepared people, let alone heartbroken family members, should be left to carry the weight of another’s health, their existence. We’ll only crumble under that weight.