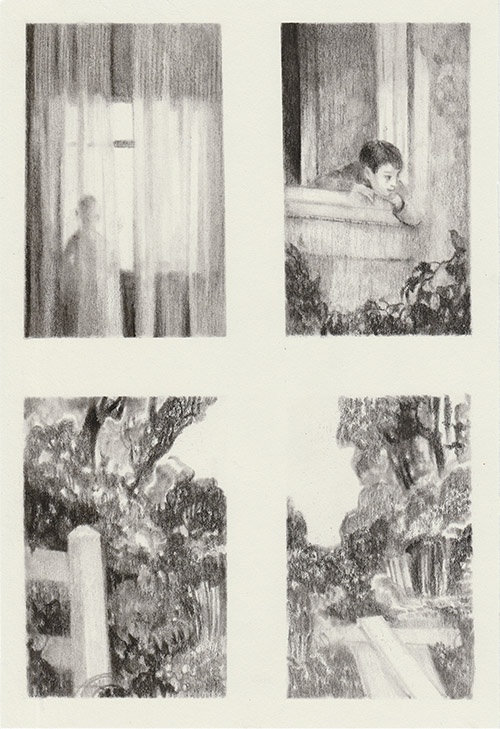

"Beyond the Walls (2020)" by Katty Maurey.

"Beyond the Walls (2020)" by Katty Maurey.

Banding Together

There’s such a thing as a solitary artistic genius—and Donovan Woods remembered this spring why he wouldn’t want to be one.

I used to work at the Enterprise Rent-a-Car on Dovercourt Road, in Toronto, a job made up of little jobs: washing cars, talking to people, paperwork. I liked washing cars best because my arms did it so automatically it was like doing nothing. I could think of other things while I was doing it. And when it’s done, it’s done.

Now that I’m a musician, it’s still a bunch of little jobs combined together. I like touring around, playing shows and meeting people. But recording songs is my favourite part. I love the feeling of a recording snapping into focus and suddenly feeling important. Tiny little changes altering everything. Someone walks in, plays a part I’d never conceived of and suddenly, five minutes later, I can’t live without it. I feel like I would die for it. Making something out of nothing, over and over. It completely satisfies me to get a song pinned down correctly. It’s a feeling of relief and finality, like putting vacation pictures in a photobook. You did it, there’s proof, you can move on.

There is a myth in music about the solitary genius. Justin Vernon, bearded and heartbroken, retreating to a cabin in the woods and emerging weeks later, bleary-eyed with a brilliant Bon Iver album. God, the idea thrills me, too. But I can’t do that. I have kids. Also, I’m probably not talented enough.

The truth is that most popular music is made by groups of people. Sure, there are outliers. Elliott Smith did it all himself, I’m told. Brian Wilson, maybe? That Matthew Sweet guy from the nineties, I think. Anyway, I can’t do that. I think of myself as a songwriter; I’m not even sure I’m a musician. I get my work done ahead of time. I play my guitar parts and I sing, and then I just sit back and listen to the other parts emerge in the studio. I hire musicians I love and I let them enjoy themselves.

I started making a record in mid-February, with a plan to have it all wrapped up by April 20. The virus, of course, derailed these plans and we had to make new arrangements. Now I’m in my house every day trying to keep my kids on something that resembles a schedule. Now I’m sneaking off to the quiet of our front porch so I can listen to new parts of songs as they arrive in my inbox. Now I send text messages like this:

It sounds nice, I suppose. The arc is better. I’m wondering if the EQ on the guitar can be softened slightly. It sounds very clickety-clackety right now. I think the verse can be the stuff where it’s messy and where things are a little off and collage-y. But the feeling I love in the choruses is that each time he gets it more and more together. As if he’s trying to gather himself and get it right. Like he stands up straighter every time, you know? Like that yoga pose. And it gets more right each time. Also, I miss Robbie marking the chords in the second chorus.

We’ve been farming parts out to musicians to record in their own home studios. This is less fun than talking about music in person. It’s missing tone. It’s missing body language. It’s missing the excitement everyone feels in the studio when something is working, when everyone gets it, understands the goal and feels free to try new things. That’s when it gets good.

I just finished watching Ken Burns’s documentary on country music. In it, there’s a quote from legendary artist Roy Acuff telling the band at a recording session to get focused early on because “...you know and I know, every take loses something.”

Every musician knows this. The reason why is a bit of a mystery. You’d think proficiency matters. You’d think a room full of talented musicians who know the song inside and out would produce the best results. For some reason, that couldn’t be further from the truth. The thing I like best is hearing a talented person figuring something out. In the studio you can facilitate this by introducing people to the music at your own pace—just by not letting them hear songs until they’re suddenly playing on them. I find myself saying things like, “Play it like you’ve never seen a piano,” to people who’ve been playing since age five. “Do it like you literally just figured out what the soft pedal does.” Or just by explaining the story I’m trying to tell in the song, and the feeling I’m trying to capture. To me, making music for people is saying “Sometimes I feel like this—do you ever feel like that?”

Maybe recorded music is best when you can hear that conversation going on in the studio as well. When you can hear a bunch of musicians trying not just to play the song, but trying to empathize with the songwriter’s point of view.

My producer and friend James Bunton and I are discovering ways to reproduce these conditions remotely. Sometimes by telling a musician to play over a whole song, when we’re only looking for one little part. Sometimes by just saying “Don’t listen to this until you’re recording.” Other times we do it by just pulling apart the songs and putting them back together in a way that feels haphazard, then using that as a jumping-off point.

Every time you finish a record, it feels like you’ll never be able to do it again. It feels like some unrepeatable stroke of luck saved you. Like the songs serendipitously showed up when you needed them, or a musician with a great part saved a song from being abandoned.

And with this particular album, I feel lucky we got to experience this strange process, too, in the middle of the pandemic. Despite everything, I think we’ve captured a raw feeling of musical discovery. We did a good job of displaying my writing process inside the final product—this album has more of a handmade feel than my others; you can hear where the songs started and where they ended up. I even think it’s the best collection of songs with my name on it so far.

But of course I think that. I make sure I feel that way with every album. If I didn’t, I would quit and work at a car wash.