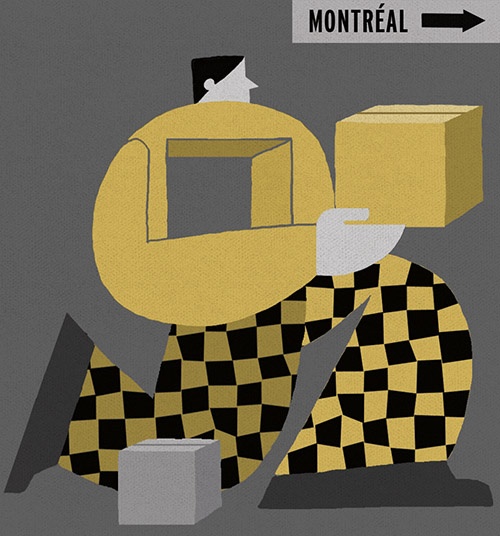

Illustration by Boris Biberdzic.

Illustration by Boris Biberdzic.

Filling the Void

A pesky meme keeps saying Montreal’s overhyped. Is it right?

I came of age in a city known for being the best place on earth to get deliriously drunk in cowboy gear for ten days every July. As a teenager, I took my lunches in the art room of a grey, prisonesque high school where it was against the rules to—God forbid—display art on the walls. I’d put on the 500 Days of Summer soundtrack, baiting for a kindred spirit.

As you could imagine, it was a big deal to people like me when Calgary's first Urban Outfitters opened. My best friend got a job there; in fact, hip kids from across the city flocked to that little corner of Chinook Mall.

And then, a couple of years later, a not-insignificant number of those employees up and moved to Montreal, my best friend included. I had moved east too and was halfway through my undergraduate degree in Ottawa when she made the leap. I watched as she snagged a spacious two-bedroom avec deux balcons for $800—not much more than what I was paying, barely two hours away, for a quarter of a tiny flat in the most overhyped neighbourhood of “the city that fun forgot.”

The first time I visited her, I delighted in the $9 bottle of wine I snagged at what she advised me was called “the dep.” I became obsessed with her neighbourhood fruiterie, cradling my $3 chunk of cheese like both a baby and a trophy. We lounged around the Musée des Beaux-Arts for free. Everyone was stylish and good-looking. What wasn’t there to love about Montreal?

Then, in the fall of 2017, an image started making the rounds on Twitter and Facebook. It was a simple sentence on a pastel gradient: “Moving to Montreal Won’t Fill the Void.”

I wasn’t ready to confess that the handful of words hurt my feelings, so I was happy when someone on Twitter did it for me. “I’d rather not admit the extent to which [the meme] impacted my decision to delay moving for the indefinite future,” wrote Twitter user @lil_pout. The meme dampens the romance; it feels like a firm no to your secret longings, as if from a stern parent.

Looking at its (wide) circulation more closely, it seemed the meme especially resonated in Western Canadian circles, echoing wryly all the way from Vancouver to Saskatoon. I couldn’t help but wonder: why do so many Western Canadian anglos feel drawn to a city in la belle province in the first place? And why, then, are they also hating that feeling?

I should know: I recently made the move anyway.

Moving to Montreal from out West can be a particularly naive act of recklessness. It’s commonly a move without a plan, where all the decisions that should be made by logic are handed off to her temperamental cousin, feeling.

It made no sense for someone from Calgary, a city so far from bilingualism that transit passes printed en français were mistaken as forgery by bus drivers in a 2019 incident, to come here. My conversational skills in French were that of a nervous robot at best.

There are many dimensions to the siren call of Montreal: affordability, lifestyle. And those two things are often inextricable. Adam Cathey, who helped me pick up some second-hand furniture for my new apartment in the van he’d driven from Vancouver, told me everyone he knew in Vancouver worked two jobs just to get by, leaving time for little else. “In Montreal, it’s almost a faux pas to ask what you do for a living,” he says. “Instead, people want to know what you do for fun.”

For young Canadians mapping out their lives, first you have to narrow things down to the cities you can afford to live in (sayonara, Toronto and Vancouver). This is an age-old argument for living in Montreal, but as the average monthly price of a two-bedroom hits about $2,900 in Toronto and about $3,000 in Vancouver, it’s still a compelling one.

Courtney Chaney, a University of Victoria visual arts alum from Seattle, chose Montreal as her next home before even having visited. If someone’s experiencing a “void feeling,” Montreal lets them maintain a quality of life in the meantime, she explains: “Doing things that they want to do, being curious, having enough time in their day to do a little soul-searching.” Chaney spent her first few months in Montreal living off odd jobs, making art, taking French classes and researching grad schools.

Rachel Holloway made the move from Calgary on the heels of a breakup. She had no plan—just a cheap apartment her friend had secured, dreams of snagging an internship at her favourite Montreal magazine and an urgent desire to get out of Calgary. “I think Montreal is kind of like chaos,” she says. “So people with, like, chaotic minds come here.”

Holloway now laughs at her expectations. She landed her first job in a cafe more than an hour’s commute from her apartment and has since scraped by in various behind-the-counter positions using her small (but growing) French vocabulary. Other transplants get by cleaning Airbnbs, working at call centres, testing video games.

For born-and-raised Quebecers, the self-imposed exile we’ve willingly walked into must be baffling. We have most of the country at our fingertips; why would we want to do this? Trying to achieve a working-level capability in a new language can seem nearly impossible. Anglophones know it, too—we’re signing up to struggle in Quebec. Yet for decades, the city’s promises have still seemed to be worth it.

My own decision to move to Montreal involved a tangled mess of factors. Ottawa was a terribly comfortable city that I felt I could accidentally sink into, like a trance, and wake up at age forty-three with a government comms job, a house in the sprawling suburb of Kanata, 2.5 children and a husband who largely ignores me.

More than anything, though, I didn’t want to go home.

The “Wexit” movement has been picking up steam in my home province and most recently includes my dad, who works in the oil industry. Alberta is a place that feels less and less like home the longer I’m away from it, which is perhaps the inverse of homesickness. At times, I’d imagine what it would be like to return after graduation. Calgary is struggling, and I feel immense guilt for leaving my family and friends.

But whenever I return, I am reminded why I’d have a hard time calling it home. Calgary drives, Montreal metro-s. Calgary largely denies climate change, Montreal hosted the largest climate strike in the country. Calgary, of late, is clinging to the corpse of its oil-oriented economy for dear life, and everyone is hurting.

There are immense complexities and nuances to Alberta’s struggles that are trivialized in Eastern Canada and that I always try to explain to non-Albertans. But still, I couldn’t bring myself to make the move back.

I’m not the only one. While Calgary is growing, the number of twenty- to twenty-four-year-olds in the city is rapidly shrinking, according to a recent report by the CBC. The twenty-somethings quoted in the article cite similar feelings to mine: disillusion with the oil industry, a lack of arts and culture, a lack of job opportunities.

Quebec's economy is thriving. And I wanted to try on a new city brimming with its own unique anecdotes and strange people. I wanted to have my (Canadian) Sex and the City moment. And with a fun French twist! I’d tell myself on my particularly cheery days.

I arrived in town in a pickup truck full of my belongings covered in a tarp that had been rained on for the entire two-hour drive. Rain pelted my mattress as I dragged it up a steep, slippery flight of characteristic outdoor stairs. That first day marked the beginning of a trend of general unpreparedness for me in Montreal.

The knot at the pit of my stomach grew bigger and bigger as I encountered the inevitable “Bilingualism: essential” at the very bottom of every job posting. Turned out that burning-hot economy was just beyond my reach. There were bigger disappointments, too. Recently Montreal rents have risen so fast, and the vacancy rate plummeted so steeply, that apartment-hunting could approach Toronto-level painfulness some not-so-distant day. And Quebec shares some nasty similarities with my home province, I’ve realized, like a culture with a higher tolerance of racism and Islamophobia.

One day, in the checkout line at the grocery store, an elderly man tried to share a moment of connection with me over—I’m pretty sure—matching items in our carts. He spoke to me excitedly in French and I didn’t know how to respond, so I laughed and smiled cartoonishly, as I find myself often doing these days.

It was objectively stupid for me to move here. Montreal isn’t the low-cost refuge it once was. Culture and pretty buildings only do so much good when you’re struggling to get by.

My void isn’t really gone. The void, in itself, is a hard concept to define. It is a feeling of perpetual scarcity—a little nagging voice in your ear, suggesting that your current circumstances aren’t good enough. For Western Canadians, you can’t change your circumstances more than going to Montreal. At least we want to think so.

I turned back to the internet one last time, to see how other people handle this grass-is-greener trap. It led me to Emily Klatt, a twenty-something from Saskatoon. She was intrigued by the idea of moving to Montreal, but then a handful of her friends moved there and boomeranged back to the prairies within a year.

Klatt’s friends couldn’t find work, but perhaps more importantly, the fun that was supposed to make up for living hand to mouth, the eternal balance of Montreal, wasn’t there. “I guess one thing that happened,” Klatt's friend told her after moving home, “was that I had access to a lot more music and concerts in general but I didn’t always feel that I had the extra cash or time to go to them.” A few years ago, most void-fillers would have been able to find an apartment downtownish. The friend, like so many these days, was living farther away. Klatt decided to stay in Saskatoon and learn to make her own bagels.

Hearing about the bagels made me realize: moving to Montreal was still worth it for me.

Scavenging for shiny moments here makes it worthwhile, whether or not you find exactly what you expected. There’s a world of Québécois teen heartthrobs, television and tourtière that makes it feel like a little country was hidden within my country this whole time. I called my boyfriend “mon chum” over and over upon first discovering it, to his dismay. (He still refuses to refer to me as “ma blonde.”) I collect these things like little trinkets.

Maybe I just managed to strike that Montreal balance. And maybe that’s just a question of luck these days, whereas it was once the city’s guarantee. I still think it’s worth a shot; even if rents are rising here, Vancouver and Toronto are also growing so much more expensive each year that I barely allow myself to daydream about potential lives there anymore. I’m content with the three-digit rent of my one-bedroom. The bittersweet truth is that if you’re young and seeking something grand in Canada, Montreal is one of your only options, even if it’s not what it once was.

Not unrelated: you’ll be constantly reminded of the cliché of moving to Montreal, and how many generations have done this before you (with more ease). Come to terms with the fact that you’re not the only artist, writer or musician to arrive here planning to reinvent yourself. After all, that’s what gives the meme its sting; most people drawn to this city don’t like to see themselves as part of the mainstream.

If you can accept all this, you’re ready to move to the Montreal of 2020.

Anyway, filling the void is about something else, too. Partway through this year’s Christmas drive from Calgary to Medicine Hat, I realized something. A familiar smell hit my nose, and I broke into a little grin. I’d forgotten about the sensory signal that you’re halfway there—the imposing scent of Brooks, a tiny town of cattle slaughterhouses. It was putrid, and it was so Alberta.

And for the first time, I loved it for that.