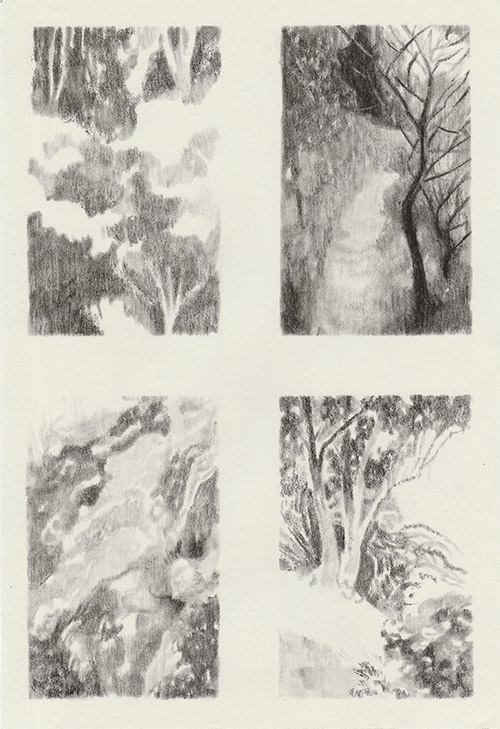

"Beyond the Walls (2020)" by Katty Maurey.

"Beyond the Walls (2020)" by Katty Maurey.

Highs and Lows

Letter from Montreal.

When I glance out the window of my home office, I see the iconic cross atop Mount Royal. The base of “the Mountain”—as Montrealers call the modest triple-peaked hill in the middle of the island—is 771 metres from my front door. (The kind of trivial information you know when you’re a runner-slash-data-geek with a GPS-equipped watch.)

Mount Royal has been my unofficial backyard (or, more precisely, front yard) for the past three decades. I run there in the morning. I walk across it on my way to work, and home again. When out-of-towners visit, the first order of business is a jaunt to the Kondiaronk Belvedere, where there is a breathtaking view of downtown Montreal, complete with its Leonard Cohen mural, and the St. Lawrence River—a ritual that makes you feel you’ve earned the subsequent visit to Schwartz’s or La Banquise.

I’ve always taken the Mountain for granted. But Covid-19 has given me a new appreciation of this oasis.

As a health journalist living in the epicentre of the Canadian outbreak, my life has been consumed by Covid-19. I’ve spent every day since mid-January glued to the computer, watching and writing the news, perhaps with a little more sense than the regular reader of how bad it could get.

Thankfully, I have an antidote to the stress. By the time I stroll past two Portuguese chicken restaurants (Romados and Portugalia) and I can see the trees of Mount Royal, the anxiety has already lifted.

I could navigate Chemin Olmsted, the 5.5-kilometre-long winding dirt road that leads from the Sir George-Étienne Cartier monument to the cross, with my eyes closed—though not necessarily without the occasional stumble, and I have the scars to prove it.

I know where to go to watch the Cooper’s hawks soar and hunt pigeons, the spots where the chickadees will feed from your hand, the area where you might spot a shy red fox, the muddy bogs where kids can catch salamanders, and the meandering forest paths that make you feel far from the city.

For early morning runners like myself, the pandemic has changed our routine very little. The coronavirus-related backlash is laughable; runners are social distancers by nature, loners who exchange polite nods in passing, not germ bombs.

What is most noticeable during my morning jaunts is what is no longer there. The playgrounds are closed to children. No one is staking out a picnic table for a birthday or family gathering. Access to paths and stairs—even the lung-bursting 339-step staircase up the escarpment—is blocked with unsightly police tape, though this tape is routinely torn down. Montrealers are not, by nature, rule-followers; in a city where stop signs are largely decorative, it takes more than a bit of tape to keep people from their beloved Mount Royal.

The giant eyesore of a parking lot near Smith House is mercifully empty. Tour buses are no longer idling and disgorging hordes. That seems to have left the raccoons and squirrels perplexed and scrawny; they have always counted on the tourists, not the locals, to feed them.

Santa Cruz Church and community centre, a nearby hub for the Portuguese community, is eerily quiet. The field where football and soccer teams battle for supremacy is locked tight. The “Tam-tams,” a popular Sunday gathering for drummers and dancers, has fallen prey to rules of physical distancing. The overwhelming smell of pot is no longer there, though a few die-hards have tried to keep the toking and drumming tradition alive—at a two-metre distance, of course.

Yet you can’t totally escape the grim reminders that death and suffering are close by. Four hospitals are built on the flanks of Mount Royal, and as many cemeteries. The Mountain has been a burial ground for centuries, if not millennia, and is home to Canada’s largest cemetery, Notre-Dame-des-Neiges. Given the Covid-19 carnage, the cemeteries are busy, yet closed to visitors. One morning, I watched a family, flowers in hand, stare mournfully through the fence.

As the lockdown drags on, many more stir-crazy people begin to flock to Mount Royal. The warmer spring days arrive, along with police busy with crowd control. There is not enough room to contain the angst, even in a two-hundred-hectare park.

When I head up there on a weekend with family, there is palatable concern, if not fear, in the air. Masks are commonplace. Walkers try to give a wide berth to other walkers, and angry words are exchanged—often in an impressive multitude of languages—when someone comes too close.

Still, I know that the next morning, around sunrise, it will be quiet again. That 771-metre path to freedom will beckon and, beyond it, momentary mountain bliss.