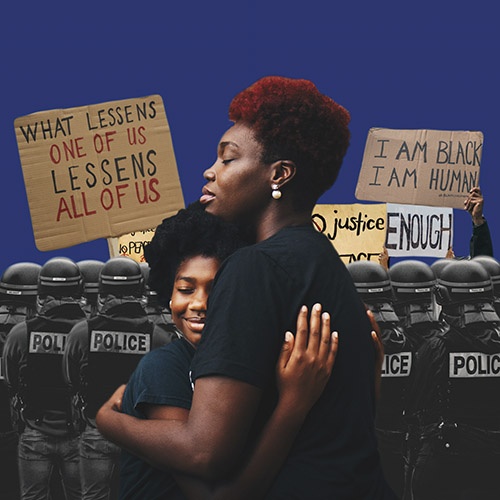

Illustration by TonyTones of XVXY Photo.

Illustration by TonyTones of XVXY Photo.

Call to Witness

Steph Wong Ken took to the streets this summer to declare that Black Lives Matter. But at home, she learned, listening was just as important.

At around 2AM, several nights a week, my father finishes cleaning the bakery he co-owns with my mother and drives through Calgary streets to the inner-city home where they’ve lived for eighteen years. Some nights there is barely anyone else on the road, the result of urban sprawl and a dead downtown. Some nights a police officer follows him silently for twenty minutes, only pulling away once my father makes the cautious signal to turn into the alleyway to his home.

When my father first told my family about this, last summer, he did so calmly at the dinner table, like he was telling us about a stranger who accosted him on the street and occupied a few minutes of his free time. My eyes widened as he spoke, visualizing the gun in the police officer’s holster and, most of all, my father’s aloneness as he drove slowly through empty streets with few to no witnesses, pretending not to notice the car tailing him.

He shrugged his shoulders and rubbed the side of his mouth, shifting in his chair. It was a move I recognized well, one I’d seen since childhood, often long after an uncomfortable moment involving racism—the aftermath of being wronged and trying to let those emotions go. A familiar shrug that said what can you do, this is how it is and it isn’t all that bad because I’m here, aren’t I?

My father has lived in Canada for over twenty years, moving to Calgary from New York City. Born in Kingston, Jamaica, he left the island at the tail end of the country’s brain drain in the early 1970s, a member of the educated middle class, hungry for better prospects.

New York City was rough and wild when he arrived. But it was also where he met my Chinese mother, at a basement party in the Bronx, and where he saw art-house movies at the 54th Street cinema for the first time. My father recalls hanging out with a group of Black male friends, checking out bars and clubs. Though they accepted him as one of them, he always knew his experience was a bit different. He was lighter-skinned, not quite the same kind of Black. He was aware of the real world implications of colourism—how discrimination against racialized people can vary depending on the darkness of one’s skin—and that his ancestry was steeped in diaspora and island culture, rather than the African American experience.

To his biography, I could add that my father is a business owner, a taxpayer, a husband—humanizing qualities, but I hate that I have to invoke these details to make him seem less deserving of being targeted by the police and put in harm’s way. He has experienced racism in every place he has lived. But he tells me about experiences in Calgary with extra clarity. Maybe it’s because they are the freshest or maybe because he only wants to share so much.

A week after the dinner-table conversation, I marched down 17th Avenue, the busiest bar street in Calgary, with hundreds of people in face masks protesting police brutality in support of the Black Lives Matter movement. The names of those murdered by police were written on signs and repeated aloud over and over by the crowd. People drinking beers on patios in the sun gawked as we made our way down the street, the jangle of bar music drowned out by chants of “no justice, no peace.”

My father knew I was going, but when I mentioned it to him, he brought up his fears of violence, of being confronted by the cops. He told me to be careful. As I marched for seven hours with friends and strangers, I kept thinking about something my father has often said about his relationship with the police: “I try not to be too bothered by them,” he said, “and I always try to comply.”

How would I Always Comply come across on a protest sign held over my head next to Black Lives Matter and No Racist Police? Sardonic or even a bit pithy, I realized, when really my father meant it sincerely, as a word of advice and a way to live, a means of survival. While I respected where he was coming from, I found it deeply troubling that he believed this was his only option.

Until the pandemic hit, there wasn’t a lot of talk about mistreatment by the police in my family. It was only in Covid-19 isolation that we began spending more time together. We talked on video chat first, and then, as the case numbers went down, at family dinners that stretched from the usual four hours to sometimes five or six hours a night, lingering over many cups of tea. These conversations emerged slowly as images of Black people being killed by the police swirled around us. Another Black man was murdered by police on the street, and another Black woman was killed in her home because the police thought she was someone else.

My Instagram feed became a Racism 101 course made up of memes and soundbites, images of sourdough starter and quarantine boredom replaced with systemic racism infographics and urgent calls to action. Though I eyed this performative wokeness with suspicion, at least when it came from certain quarters, my sisters and I began to talk about these issues more openly in group chats with friends and family. We shared links to local activism as well as our frustrations about the microaggressions we’ve experienced regularly.

It was like a dam had broken and all the messiness of living as a visible minority spilled out into our communities and our relationships. I suddenly felt more comfortable naming racism for what it was around my parents, revisiting moments I had shrugged off or swallowed with no external reaction. Beyond virtue signalling, posts on social media normalized terms like “systemic racism” and“unconscious bias,” even if they were being used by trolls or right-wing media. The words were being spoken and traded beyond the confines of an academic social justice course; they became more than that nagging feeling that lives just under the surface, shared among non-white people in private spaces.

Still, my father bristled at the term “white people” whenever my sisters or I used it. His reaction made me uncomfortable and confused, reinforcing the divide between us. Maybe he didn’t understand that we used the term to call out a group that holds power in society and in our lives, to challenge this power dynamic. But his reaction might also have reflected something deeper—that in saying the words “white people,” he’d be forced to confront his fears around naming racism aloud, and distinguish himself as a racialized person.

During our dinner conversations he often flip-flopped between arguing for change and resigning himself to minding his own business. He reminded me that he and my mother have had a lot of opportunities in Canada—many more than if they had stayed in Jamaica or New York. And then in the next breath, he recalled the political strivings of Bob Marley, who advocated for a Black uprising and the overthrow of systemic racism, lyrics that are often missed among the rock-steady vibes of his music. Some days, my father responded indignantly to new incidents of police brutality against a Black man, and other days, he argued for the value of abiding by the law and not putting yourself in harm’s way.

As we talked, a gap emerged. Spurred on by our peers, leaders and the internet, my sisters and I, in our thirties and early twenties, were vocal, intent on thriving even in conservative Calgary. My father, on the other hand, often subscribed to the mentality of survival, assimilation, and keeping quiet. Sitting next to my father at the dinner table, I reacted to his experiences with rage, even when he didn’t. But with my anger came a sickening sense of privilege. I realized I was able to feel that rage without also feeling under threat—exactly because he had carried these experiences on his own, a form of protection for himself and for us, denying himself access to safety and stability for most of his life.

Black Lives Matter and racial justice reform has become a more common topic of conversation globally and in Canada, reshaping the way institutions and white people talk about race. But it has deeply affected communities and families of colour as well, laying bare the generational toll of racism.

The gap between my father’s perspective and mine often felt like an unbridgeable divide, each of us locked in our respective roles, cemented by a world unlikely to be changed by a few conversations. Listening to my father retell his experiences of racism helped me understand him in new, meaningful ways, but it also created a kind of distance between us.

As my family was having these discussions over dinner, Calgary city council was holding a public hearing on anti-racism. For three days in early July, over 150 people spoke to a panel of eleven city councillors, Mayor Naheed Nenshi and five Métis, Black and Asian Canadian community experts about their experiences of racism, often involving the Calgary police. A petition by the Canadian Cultural Mosaic Foundation (CCMF), a Calgary-based nonprofit run by young Calgarians, had garnered seventy thousand signatures asking for a public consultation.

The hearing happened digitally and was live-streamed on the organization’s website. It marked the first time I had tuned into anything related to city council. Every morning I made a big pot of coffee and listened to Black, Brown and Indigenous people, and other people of colour, expressing their frustration and rage. My sisters and I messaged each other throughout the day, glued to the proceedings.

As we eagerly followed the panel, my father was busy working at the store with my mother. He was aware it was happening but seemed less motivated to watch, more weary. It was one more sign of the gap between us. From my perspective, the hearings felt necessary and historic, particularly for Calgary, where communities of colour are often disregarded or, worse, erased. But my father did not tune into them or talk about them much. I wondered what he thought of them. My guess is that, to him, the hearings might not have felt as moving or meaningful. He seemed suspicious of their formality and doubtful that the panel would lead to any real change.

At the panel, some speakers provided well-prepared, well-articulated statements about their personal histories with racism, while others threw out their prepared script for something less measured and practiced, their presentations echoing one another, confirming each other’s stories. “My first experience of racism happened at the age of five,” one speaker said. An activist named Shuana Porter said, “This is anger. This is hurt. This is five hundred years of PTSD passed down from my ancestors.” Some people opted not to share their own experiences of racism, saying they didn’t feel safe enough to do so within the space and format of the panel, and referenced detailed reports on the prevalence of racism in Canada’s legal system instead.

As I listened to Brown and Black men speak about racist police encounters during traffic stops and “ID checks” on the street, I heard the scenes my father also described, speaking to a pattern of abuse that criss-crosses generations. It has been over two years since Alberta’s government committed to reviewing the police practice of carding, or street checks—their common practice of stopping people, who are often Black and Indigenous, on the street for no justifiable reason. But still, no concrete action has been taken, a troubling fact echoed by several speakers at the panel.

Many of the speakers were Gen Z, some still in high school, though this could have been partly because those who weren’t familiar with Zoom or social media couldn’t participate as easily. But I think it also reflects the level of discomfort and distrust among older people of colour when it comes to institutional spaces, particularly when asked to publicly share their trauma and pain—people like my father. After all, what assurances do they have that their testimonies will matter and action will be taken when things remain the same, or only seem to be getting worse?

As the hearings went on, I noticed another pattern: often the most powerful speakers were those who disregarded the allotted time limit (five minutes each) and critiqued the proceedings themselves. They were indicative, they said, of the very system they were seeking to probe. And they were right: the problems with the format became clearer as the hearings continued. The setup asked non-white people to testify about their own experiences of racism to a panel of mostly white people, within a limited amount of time, and within a setting that historically has not been welcoming towards them. Many speakers rushed through their prepared notes to keep within the time limit, or were not able to keep their comments brief as they spoke slowly and thoughtfully of their painful experiences with the police.

One of the instructions for speakers was also to bring up possible solutions to the issue at hand—which some participants did graciously and voluntarily. They detailed plans to invest in community-based services for mental health calls, to which the police are usually dispatched, and to commit once again to reviewing the police’s street-check system, among other ideas. Still, the panel suffered from the same faulty logic common to many anti-racist panels, hearings and tribunals: it asked non-white people to recall trauma caused by systemic racism, while also coming up with ways to address the harm that the system has caused. Show us your humanity, these panels tell their speakers, and we’ll show you how much we care.

The CCMF and another social justice organization made up of mostly Black Gen Z, called the United Black People Allyship, later contested the format of the hearing, comparing it to herding cattle, and pointed out the danger of throwing everyone into one group—labelling them all “BIPOC”—without considering each group’s complex relationship to racism individually, particularly Black Calgarians’.

One of the other sticking points of the panel was the presence of Mayor Nenshi, who was elected in 2010. The first Muslim mayor of a Canadian city, his grassroots campaign and election win was seen as a potential tipping point for the city, with his faith and background front and centre, as well as his younger demographic of supporters. His election represented a move to potentially disrupt the historically white halls of the mayoral office. Ten years later, racial issues persist at all levels of city government and don’t seem to be getting better, even incrementally, a fact noted by several speakers at the panel as well as Nenshi himself. In his opening remarks, he recounted being asked why he hasn’t fixed this issue as a person of colour and as the mayor. “You wouldn’t ask a white mayor, as the very first question, ‘What have you done to solve systemic racism in your community?’” he said.

Nenshi’s comment is a reminder of the collective action needed to actually address systemic racism and dismantle it, rather than place this responsibility on one person of colour in a position of power. But it also speaks to the ways governments continue to put the burden of action on those with firsthand experiences of what it’s like to be a racialized person, carrying the bodily memory of discomfort and fear.

In September, two months after the panel, the Calgary Police Service agreed to report on “anti-racism work currently underway,” vague terms for a systemic problem so clearly articulated by those 150 speakers. In October, the city founded an anti-racism action committee to continue the community conversation. Not only does this step fail to reflect the urgency conveyed at the anti-racism panel, it also seems to suggest more trauma must be shared for direct action to be taken.

This outcome was infuriating and slow-moving. Though I should have lowered my expectations based on what has happened in the past, I’ll admit I was still a little surprised. The panel had felt affirming to me, even with its flaws, and I naively thought it would have a bigger impact than it seemed to in the end. A part of me couldn’t help but feel that maybe my father had been right to harbour his doubts.

In the early eighties, before they had kids, my parents visited Banff to see the mountains. On the trip, a police officer pulled them over on the highway and asked my father to step out of the car. When my father questioned why he’d been pulled over, the officer pushed him, and my father, in a moment of anger, told him to stop. The officer eventually let him go with a warning, likely because other cars were passing by and both my father and the officer knew people were watching. There is no official police account of this interaction, and no certain witnesses except for my mother, father and the officer. Still, my father describes this moment with clarity and detail twenty years later.

Our access to evidence of these encounters has changed: now, we can watch cellphone videos of police shooting unarmed Black men, some of the videos taken from the body cams they are sometimes required to wear. There are also witness accounts of police brutality against non-white people who suffer from mental illness or who are houseless, police using excess force against these bodies in all manner of ways, from guns to tasers to arms, hands and knees. And now, with the anti-racism hearings, Calgary has its own public record of firsthand accounts of racially motivated violence enacted by the police. The speakers at the panel were able to write their stories into that record in ways my father hasn’t been able to do for much of his life, forcing a public audience to witness and acknowledge their pain. But this confirmation alone cannot undo the trauma of their experiences, or shift long-established ways of living with that trauma.

I worry about my father. As studies confirm the effects of intergenerational trauma on physical and mental health for people of colour, I wonder about the link between his sudden fits of anger, masked by the mellow “irie” vibes of his Jamaican roots, and his inability to express his anger or frustration to the countless officers who have pulled him over and continue to do so. This inaccessibility brings to mind the concept of double consciousness, of what W.E.B. Du Bois calls “two warring ideals in one dark body.” For Du Bois, Black people are caught between being African and being American, conflicted by their desire for self-development beyond these two ideals.

I think this sense of double consciousness and displacement never really leaves, regardless of age or generation. Encounters with the police become painful, potentially fatal, reminders of always being in conflict, unable to feel settled and at peace.

When I asked my father why he finally felt comfortable enough to share his experiences at our dinner table, he responded that it was because I had asked. I asked the question, “have you experienced this before?” He felt it might be of some value to his daughters, a sign of encouragement to us, the current generation, to continue to protest and speak up.

He was also sensitive to the larger conversation happening around us—Black Lives Matter protests happening all over the world, including Calgary. By deciding to lean on a louder generation, with tools he never had, he might have been testing the value of speaking aloud in the company of those he felt safe enough to talk to.

His hesitancy to share his experiences beyond our family circle doesn’t make me value our conversations any less; I see them as a bridge between us, between his world and mine. Though our approaches might be different, I do think we are trying to work towards a common goal, a sustained sense of change.

In fact, much like watching the speakers at the anti-racism panel, hearing about my father’s experiences shifts my position from listener to witness. Through his telling, the experiences become more than just moments he was forced to inhabit, alone. I don’t know if the gap between us will ever fully disappear, but witnessing him as he speaks does help to close it. Our conversations mean he no longer has to hide the extra weight of his experiences or carry them alone. Even so, I’m aware that I still can’t guarantee his safety, or that the system that endangers him will not do so again.

Recently, two police officers stopped my father on his way home late at night and told him to pull over to a side street for a check. He showed them his license and registration, unsure what they meant by a “check.” They let him go and he said, “thank you very much,” before driving slowly in the opposite direction of the police—and of where he’d been headed. Another day, another encounter, and when he tells us at the dinner table, I listen, and I witness.

Sometimes, I recreate these scenes in my mind, but I remove the police officer and focus instead on my father driving home in his adopted city, cruising down a calm, quiet street that holds no malice or threat. I like to conjure this revised version, though I know it is so far from our shared reality. It is a fiction, and still, I keep imagining it.

Born in Calgary and raised in Florida, Steph Wong Ken is a writer currently based in Toronto. Her writing has appeared in the Walrus, Catapult and C Magazine, among other outlets. Find her work at stephwongken.com.