The Winter 2020 Book Room

Winter reads from Eli Tareq El-Bechelany-Lynch, Sheung-King, Dakota McFadzean and others.

Daniil and Vanya

In her first novel, Marie-Hélène Larochelle leads us down a dark path that involves murder, lies and sexual assault. Not quite a horror nor a thriller, Daniil and Vanya (Invisible Publishing) is subtle in its uneasy sordidness. Translated from the original French by Michelle Winters, the story stars a seemingly picture-perfect French-Canadian couple. But we quickly find out that there is no warmth to be found between the pair. Emma is pitifully materialistic, obsessed with how others perceive her and her role as mother to adopted twin boys Daniil and Vanya. Her husband Gregory is ultra-vain, the epitome of a mansplainer. Their twins, meanwhile, begin to exhibit strange, perverse behaviour. The boys are without empathy, and focus solely on their own unsettling and unspoken shared goals. They seem to communicate telepathically. The tone of Larochelle’s novel is nonchalant, but what she describes is a carnival of the grotesque: a boy is sadistically injured, a cat is maimed and children assault other children. While this novel warrants a content warning for self-harm, mental illness and various forms of abuse, its disturbing nature is gripping, and will keep you hooked.—Chloë Lalonde

To Know You’re Alive

Some of our most frightening childhood experiences can stem from the most mundane situations. Dakota McFadzean understands this well, and his new collection of graphic shorts explores a wide range of inexplicable childhood anxieties—ones that seem to emerge from the void but can leave us destabilized well into adulthood. The stories in To Know You’re Alive (Conundrum Press) dive into the fraught social dynamics of grade school. They show the cartoon characters on a cereal box coming alive as a kid eats breakfast, and haunting that kid for the rest of their days. They follow a girl finding a deer skull in the suburban wilderness, a discovery which is at once ominous and transformative. Slow pacing and deliberate pauses in action add to the artist’s depictions of the grotesque, the alien and the surreal, drawing out the terror of the situations at hand. To Know You’re Alive tells us that we won’t always sort out what causes us to be consumed by fear, but reassures us that we’ll be okay anyway.—Steven Zhu

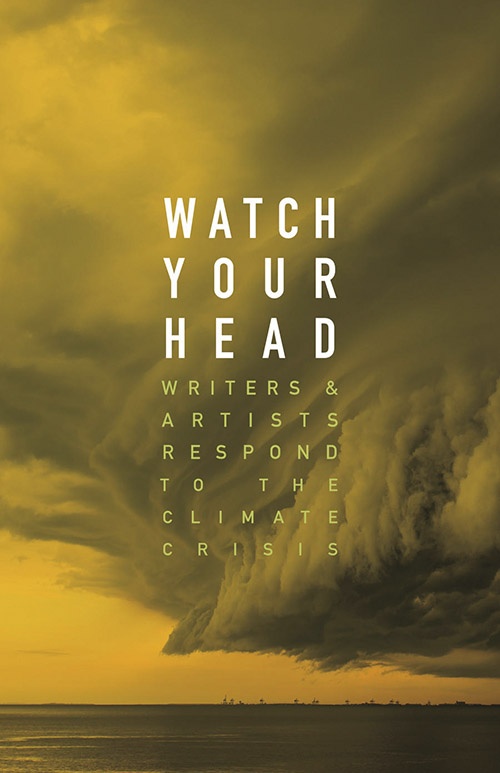

Watch Your Head

How do we grapple with an emergency the scale of the climate crisis? Over eighty Canadian writers and artists help show us the way in the anthology Watch Your Head (Coach House). The collection includes anxious and angry stories, essays, poetry and art about environmental dangers, the ongoing oppression of Indigenous peoples, and possible future realities. A clever comic by Sarah Mangle highlights the social confusion and apathy that people often feel when climate change comes up in small talk with friends. A poem by Terese Mason Pierre uses repetition of the words “we will tell them” to emphasize our environmental impacts on the next generation. An essay by Rita Wong details her experience being sent to prison for blocking work on the Trans Mountain pipeline, which was set to travel through unceded Coast Salish territory. Watch Your Head’s contributors all fear the future and grieve the losses—human and environmental—to come. But they also stress the importance of taking action to change the way we live. The anthology can be difficult to read, but it manages to convey the urgency of the climate crisis while leaving us hopeful that we can work together to clean up our mess.—Callie Giaccone

You Are Eating An Orange. You Are Naked.

In Sheung-King’s debut novel, a twenty-year-old translator floats between his condo in Toronto and hotel rooms and restaurants across East Asia and Europe. His unnamed girlfriend joins him on these trips, all of which are recounted through a series of vignettes. The couple talks about folk tales, literature and philosophy, intellectual topics that tether their otherwise fragile connection. But the narrator’s girlfriend also frequently disappears with no explanation, leaving him unmoored and alone with his thoughts. In this uncertain space, he circles around questions relating to nationality, language, Orientalism and the Western gaze. He also fixates on more immediate concerns: Is his work meaningful? How can he keep his girlfriend from growing bored with him? How literally should he respond when his local barista asks, “What’s up?” You Are Eating An Orange. You Are Naked. (Book*hug) is a delightful blend of the real and the surreal, the monumental and the mundane. Sheung-King’s characters interrupt their conversations about life’s big questions to comment on the dessert they’re eating, or to reach for a basket at the grocery store. The writing feels intimate without being overly sentimental. Reading it is like stepping into a stranger’s dream.—Madi Haslam

knot body

Anyone who has lived with stabs of chronic pain or been harassed by men is sure to find refuge in Eli Tareq El Bechelany-Lynch’s work. Those who have transitioned will feel especially seen. In knot body (Metatron Press), El Bechelany-Lynch describes the ancestral pain they inherited from their Teta (grandmother), the physical pain they live with each day, and how they care for themselves through both. They share their stories through a mix of poetry, stream-of-consciousness essays and letters addressed to “friends, lovers and in-betweens.” It’s the in-betweenness of this book that’s so real: there’s pain, yes, but also the ferocity required to get on the bus and go to work anyway, to eat with loved ones, to have sex and fall in love. Reading this collection is like getting a stick-and-poke tattoo in a not-so-painful area that reads “you are not alone.” It’s one of those works that reminds the reader their own story is worth something. Sometimes you’ll probably get a little lost, and that’s okay. Not every part of this book is for every reader, but its tender, deliberate tales will speak to many.—Sarah Ratchford