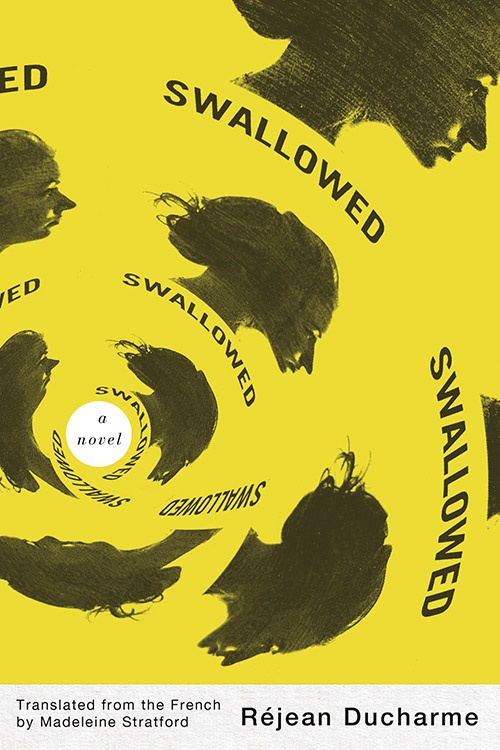

Swallowed

Writing from Quebec. Translated by Madeleine Stratford.

EDITOR'S NOTE

In 1966, Réjean Ducharme—an unknown, twenty-four-year-old Québécois writer—released his debut novel. Set in the suburbs of Montreal during the Quiet Revolution, L’Avalée des avalés follows Berenice Einberg, a rebellious eleven-year-old, as she navigates a strained relationship with her parents and the overwhelming love she feels for her brother, Christian. Ducharme published his novel in France, as his manuscript had been rejected by every publishing house in his home province. Nevertheless, the book became a sensation in Quebec. It’s been taught in schools for generations and is widely considered the foundation of modern Québécois literature. The following excerpt comes from Swallowed, Madeleine Stratford’s new translation of Ducharme’s novel. Published this fall by Véhicule Press, Stratford’s translation marks the first time an English edition of the book has been in print since 1968, and the only time that one has been available in Canada. Reprinted with permission.

Twilight has fallen and it’s rather cold out. I look up at the sky, trying to understand the dismal excitement, the dizzying fever it elicits within me, this anxious intoxication consuming my whole body. High over the horizon, a bank of jet-black clouds, as massive as a wharf, frame the blazing top of a wall that once contained the violent flares of the fall sunset. We’re besieged. The sky is about to be seized. The wind is blowing in the right direction. It will soon rain. This may be our last chance. We must burn the grass tonight. We go see the gardener. We’ve been hassling him about this since the beginning of the month. Look, Gardener, it’s going to rain, and the grass will be wet! Look, Gardener, the wind is blowing the right way; it’ll drive the flames toward the river! Defeated, utterly out of strength and arguments to fight back, the gardener gives in. He stands up, puts on his cap, and heads to the abbey to ask Einberg for permission to burn the grass.

Wielding firebrands, we set fire to the waterfront skirting the width of the island. We kindle the waist-high, rampant, bone-dry grass—broom, whin, cat’s tail and witch grass. We witness at once the extermination, slaughter, deflagration, disaster. As soon as the grass is ablaze, a single blow of the wind makes the flames roar, rise above our heads, spread on all sides—it’s as though we were caught in a flight of tufts. Before long, the flames strike, surge, scream from shore to shore, their plumes billowing below the clouds like tight herds of great white horses. Entangled in black fumes, rekindled by a mist of sparks, the flames furl and unfurl like a tidal wave. Titanic, terrifying, untamed, they sweep and spread like a tsunami, wolfing, razing, wiping everything. All they leave behind is a fine black lace of ash that turns to dust under our feet. The night sky casts a red glow. The moor crackles throughout. Christian and I are not done. We’re firebenders. That, believe me, is no small feat! We must manage the scope of the burning wave, making sure it doesn’t miss a single twig or straw. We must help it past rocky ridges, revive it when it hits a puddle, stir and feed it where the grass is scarce, bring it back to life when it dies out. We must continuously meld its countless masses together. We must look after every detail. Feckless and heedless, distracted, the gardener leaves everything to chance. I put my hands on my face. It’s burning hot. I put my hands on Christian’s face. Our eyes are crying, our lips are laughing. Neither of us can stop coughing. From the shadows, cradling her cat, Mothy Mouser watches us. Around the elm and the quarry winch, we have to corner the Hydra, hem it in, fend it off, fight with it. We swing our shovels relentlessly at every raised head. The wind dies out. The rain slowly starts to fall in small icy lumps. Intoxicating at first, the pungent fumes now make us a little nauseous. Our arms are shaking. We head home. The last gleaming glitters are fading, fainting as they reach the water’s edge. All that’s left glowing in the night are a few scattered pockets of ember. I follow Christian, exhausted, wobbly, holding my belly as I laugh in flurries, clinging with one hand to the hem of his shirt.