Photographs by Ian Willms

Photographs by Ian Willms

Seeking Sanctuary

Toronto’s homelessness crisis has reached new heights. Stephanie Bai meets members of a community fighting for their lives.

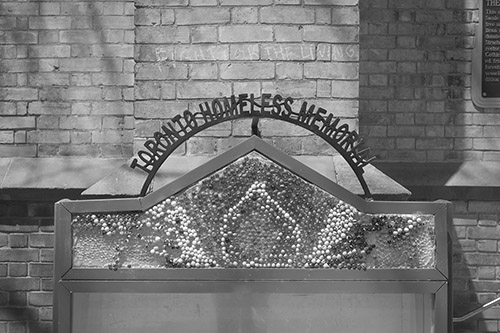

The Toronto Homeless Memorial is falling apart. Its blue frame buckles under the weight of more than one thousand names printed on the sheets of paper inside the glass case. The fifteen or so pages are fanned out like an accordion, with two columns of text on each sheet listing those who have died while unhoused. The sheets used to be reprinted every month, the font squished smaller with each new wave of deaths. Eventually, the names became nearly impossible to read.

Above the glass case is a mosaic of marbles. At its centre is a flame-like shape, filled with a ring of opalescent red and orange spheres. Colours radiate from it like stained glass. Michael “Duckie” Mallard, a tall man with a long, tapered white beard who has experienced homelessness himself, helped build the mosaic in 2019. Years ago, when I met Duckie, he told me the story of the marbles.

In 2016, when he heard about the death of his friend Bev Bernardin, a thirty-two-year-old unhoused Indigenous woman, he remembered a conversation he once had with her. “Her worker said she was losing her marbles because she preferred to be outside rather than be in a slum house,” Duckie said. “So I ran to the dollar store, I got a little medicine pouch at home, I filled it up with marbles. I gave her the medicine pouch to take to her worker and say, ‘Guess what? Mikey found my marbles!’”

Now, he passes them out in her honour. The day we met, he pulled out a plastic black container, like the ones from a Thai takeout restaurant, and lifted the lid. “You find a marble that catches your eye,” he said. I picked the first one I saw: black with orange and yellow veins, reflecting light like obsidian. Duckie peered down at me seriously. “Every time you find that marble, there’s your grandmother or your mom or your dad who’s passed away. It’s a personal thing, okay?”

The homeless memorial stands in downtown Toronto’s Trinity Square, right in front of the Church of the Holy Trinity, whose members help maintain the shrine. Thousands of unhoused people in Toronto have passed away without their names making it onto the list because they died without record in prisons, or alone in the hospital. Still, people call the church from all over the world, searching for loved ones who have disappeared. In some ways, the memorial has become a place for laying the lost and passed to rest.

On the second Tuesday of each month, the church holds a vigil to honour those who have died while living on the streets. In March 2021, twenty-seven people show up in Trinity Square, socially distanced and masked. The mix of church members, unhoused people and activists listen solemnly as unhoused community organizers lament the ways the pandemic has torn through the houseless population in the city, ravaging shelters and leaving behind a list of lost lives in its wake.

In February 2021 alone, eleven unhoused people died. On the church’s southern steps, as each name is read aloud, a heaviness sinks in. Every name sounds like another toll of the city’s hushed death knell.

The Church of the Holy Trinity is located near the Eaton Centre, clustered between the gunmetal faces of designer stores and high-rise buildings. Built in 1847, the church was founded by Mary Lambert Swale, a member of a wealthy British family who was married to an Anglican priest. Swale had heard about Toronto through Bishop John Strachan, then-head of the Anglican Church in the city. Before Swale died during childbirth in 1845, she gave Strachan five thousand pounds sterling to build a church to serve the poor. She had one stipulation: that Holy Trinity’s pews be “free and unappropriated forever.”

Among the wealthy, this was a radical sentiment for the time. During the nineteenth century, churches often made congregants pay to rent a pew, which excluded poorer families from attending services. Under Swale’s direction, Holy Trinity became an exception to this rule—all were welcome.

The church has been on the front lines of social issues ever since. In the 1960s, it was a place for draft dodgers and anti-Vietnam War protesters to unite and unwind. In the 1970s and 1980s, while police were still raiding gay bars and same-sex marriage ceremonies were prohibited by the Anglican Church of Canada, gay communities held tea dances in the nave.

In the nineties, the church began new services for the city’s unhoused population. The Toronto Homeless Memorial was founded in 1997 by the late Bonnie Briggs, a housing activist and poet who had experienced homelessness. The memorial was meant to honour those who had died unhoused and render the worsening housing crisis visible to the public. The monthly memorial vigils, organized by Briggs and a small group of Holy Trinity staff and volunteers, began in 2000 in response to the alarming rising mortality rate of unhoused people in the city.

“The memorial has been able to be a framework, if you will, for advocacy,” says Cathy Crowe, a street nurse who helped establish the vigils. Crowe has worked with the city’s unhoused population for decades and now teaches in Ryerson University’s department of politics and public administration.

She says Toronto’s housing crisis worsened in the mid-nineties, when governments axed the various federal plans that made up Canada’s national social housing program. This included cuts to funding for new housing, housing allowances and mortgage assistance. Ottawa, which once funded around twenty thousand new social housing units per year (including about 3,900 in Toronto), offloaded the responsibility to the provinces. “That’s one of the main reasons we’re in the mess we’re in right now,” says Crowe.

Around the same time, the federal government legalized the first real-estate investment trust in Canada, which allowed private equity firms to funnel money into buildings as investments. Suddenly, housing was starting to be seen as a cash grab, rather than a public good. Rents began rising across the country and securing affordable housing became more difficult.

In Toronto, the fallout of these decisions quickly became clear. Between 1999 and 2002, the encampment site Tent City popped up between downtown highways and the Harbourfront, just two kilometres away from the memorial. Unhoused residents worked with community organizers like Crowe to distribute aid around the site.

Now, two decades later, Crowe is watching a similar scene play out across the city. And despite increased advocacy and awareness around the housing crisis, she’s seen little concrete change from policymakers.

In 2016, organizers’ work related to the memorial sparked a Toronto Star investigation. It found that Ontario and most of its municipalities did not regularly track the deaths of unhoused people outside of shelters, leading to an incomplete picture of the realities of homelessness in cities like Toronto. Without this crucial data, governments were ill-equipped to address the housing crisis that has been plaguing the city for decades.

In response to the Star investigation, the City of Toronto started collecting data on the deaths of unhoused people living outside of shelters for the first time in 2017. The city said this tracking would inform its efforts to improve the health of vulnerable populations. Despite this step, the church soon discovered that its work with its unhoused neighbours was far from finished.

When Covid-19 tore through Toronto in 2020 and shut the city down, many support systems for the unhoused community shuttered with it. By May 2020, one in five Canadian charitable organizations had suspended or ceased operations, since their revenues were slashed and many relied on close-contact gatherings. Government services began to falter, as shelters had to reduce the number of beds available due to social distancing protocols. Covid-19 testing rarely reached unhoused communities.

Basic necessities like providing personal protective equipment, water, sanitation and health care for unhoused people immediately fell on the shoulders of community organizations with limited resources. Holy Trinity was one of them. After many years of honouring deaths, the church community suddenly found itself trying to keep people alive. Over the course of a few weeks, a small group of staff, volunteers and unhoused people became responsible for the lives of thousands.

Zachary Grant is sitting in their office in Holy Trinity’s old rectory with their tattoo-covered hands clasped together. Grant has served as the church’s community director since 2019. Their role involves coordinating outreach to vulnerable and marginalized populations around Toronto, including local Indigenous communities and people experiencing substance use disorder.

Grant has a long history in community organizing—they’ve worked with people living with HIV/AIDS as well as incarcerated people. Now, they want to ensure that Holy Trinity’s traditions of social activism are passed down to a younger generation of staff and volunteers. “It’s sort of our role to be one of the last vestiges of public space that’s free and available for all in the downtown core,” they say.

When the pandemic hit, Grant and their colleague Elizabeth Cummings, who helps organize donations and food services at the church, realized that the aid available for unhoused populations around the city might be affected. They were unprepared to step in—their team was only used to serving about forty unhoused people a day—but Grant says they knew they had to do something. “We just looked at each other, and we were like, ‘Are we going to really do this?’”

The church decided to stay open in accordance with Covid-19 safety measures, only allowing a small team inside the building and ensuring that all unhoused people picking up meals or other essentials remained outside. By April 2020, they were giving out about three hundred meals a day.

Tara Currie, a twenty-one-year-old culinary student, led the church’s Unity Kitchen. As head chef, she prepared thousands of meals on a single four-burner stove. The community kitchen was developed through a partnership with the Toronto Urban Native Ministry (TUNM), an Indigenous-led faith organization dedicated to serving Indigenous people in the Greater Toronto Area.

As the demand for Holy Trinity’s services grew, the church’s transformation was staggering. Before the pandemic, Holy Trinity had been a place of respite for unhoused people to escape the bitter cold or the unforgiving heat, somewhere they could have a warm meal or sleep in peace during the day. There had been maybe one rack for clothing donations.

When I visited in March 2021, the line for free meals extended almost one hundred metres from the church doors to Bay Street. At the building’s entrance, masked volunteers balanced cups of soup and plates of fruit, chatting with those at the front of the queue. Inside, racks of donated clothes crowded the nave like a consignment store. Rows of shoes lined dark wooden pews, and stained glass windows scattered jewel-toned light across sleeping bags and tubs of menstrual products.

A year earlier, an encampment site began growing around the church. People had propped up tents around Holy Trinity before, but there had only been a handful. At the height of the Trinity Square encampment site last summer, over sixty people lived in tents on church grounds.

After the pandemic hit, advocates estimate that thousands of people found refuge in tents as shelters surged to capacity and more unhoused people feared the conditions inside shelters. By May 2021, 1,553 Covid-19 cases were linked to shelter outbreaks in Toronto. In January and February 2021 alone, the city documented eighteen shelter resident deaths; in those same months in 2019, eight people died.

“Toronto has over seventy shelters, and a whole bunch of them are still what we call congregate shelters … which means that people are sleeping with many people in the same space,” says Crowe. Through the first and second waves of the pandemic, shelters often had insufficient safety measures. The city didn’t even issue a mask mandate for shelter residents until September 2020.

These missteps were especially concerning given the unhoused population has a high rate of chronic medical conditions, such as lung disease and serious heart conditions. Ontario’s unhoused population is over twenty times more likely than housed people to be hospitalized for Covid-19. They’re also over five times more likely to die within twenty-one days of a positive test, according to a study published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

So as news of the shelter outbreaks spread, people clamoured to find other places to live. The church team provided those staying in Trinity Square with food, clothing and other essential supplies as the seasons shifted. Cummings recalls how overwhelming the first few months were, especially when the weather dipped to -5 degrees Celsius. “The people we were serving—they were stuck outside,” they say. “People were shrunken.”

When the city closed all of the washrooms in the downtown core, Grant shovelled feces around the church because encampment members had no access to basic sanitation. “We all have a lot of pride and our community is strong because of this time, but we all have PTSD from how much we had to take on,” Grant says. “At that time, I mean, we were terrified.”

In one day, Jamie Watson lost almost everything. Memphis, her five-month-old son, was being treated at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto. He was born with a heart defect and was later diagnosed with liver cirrhosis. In 2016, doctors told Watson and her husband that their son had less than forty-eight hours to live. “He had never come home,” she says.

Later that day, when the couple returned to the apartment they were subletting and put their key in the door, it wouldn’t open. The person they were subletting from had been kicked out, and they lost all of their possessions that were left in the apartment. “I don’t think anything could have gotten worse after all that—juggling between a funeral and no home,” Watson says.

As a mother of eight boys, her primary concern was sheltering her other kids. She and her husband sold everything they owned that was not in the apartment, split the $30,000 between their mothers to raise their children, and began living on the streets.

Watson and her husband have lived at the Trinity Square encampment site for over a year now. Occasionally, they’ve accessed shelters, but they’ve always returned to Holy Trinity. “This is my safe spot,” Watson says. She didn’t feel comfortable in the shelters that housed forty to sixty people in a room with only dividers to separate them.

Over the past year, as thousands of unhoused people have elected to stay outdoors, four main encampment sites have formed in Toronto: Moss Park, Trinity Bellwoods Park, Alexandra Park and Lamport Stadium Park. Dozens of smaller sites have also popped up, like the one by the church.

Though some community organizations have tried to track encampment population numbers, the nomadic and sporadic nature of these sites has made collecting statistics difficult. By city approximations, there are around four hundred people staying in the encampments around Toronto. Frontline workers estimate there are, at minimum, over one thousand residents. “We’ve got our own little family here,” says Watson of Trinity Square.

People staying at the encampment site have quickly become community leaders. Dave, an Anishnawbe man from Whitefish River First Nation, founded the Native Wishing Well. Using Indigenous bushcraft and cultural practices and his background in paramedicine, he’s leading a team of other unhoused people to support any distressed people who come to Trinity Square. The team’s services include 24/7 crisis mediation, first aid and an overdose response program.

Since many harm reduction services and safe injection sites have closed or restricted their hours, the city has witnessed the devastating intersection of three crises: the opioid epidemic, the housing crisis and the Covid-19 pandemic. Between April 2019 and April 2020, 23 percent of people who died by accidental opioid toxicity in Toronto were unhoused—more than twice the number of people who died between 2017 and 2018. As mental health and social support services have become increasingly inaccessible, Dave has seen people wandering into the square in various states of crisis: some with gunshot wounds, others with no clothes on, and a few experiencing overdoses. His team treats anyone who accepts help.

Through programs like the Native Wishing Well, those in the community around the church are looking out for one another as the overburdened health-care system looks away. For a period of time, pink naloxone kits hung from tree branches over tents at Trinity Square. Another naloxone kit has been tucked into a desk drawer at the church’s entrance for years.

The Holy Trinity community has also stepped in to provide Covid-19 testing. Early on in the pandemic, if unhoused people wanted to get tested, they would have to wait in lines at hospitals and clinics that stretched for hours. But for unhoused people, who may need to get back to shelters in time for meals, the luxury of time can be in short supply.

In May 2020, Holy Trinity partnered with TUNM, Sanctuary (a Christian church that serves poor and unhoused communities) and the Centre for Wise Practices in Indigenous Health at Women’s College Hospital, which performs traditional Indigenous medical practices and ceremonies. Together, they launched what organizers believe was the city’s first mobile Covid-19 testing site at Trinity Square. It takes place on site every month, and the Anishnawbe Health Toronto team, an Indigenous-led health-care organization, has expanded the program across the city.

Time and time again, as governments and health-care systems have faltered, community members have held steady together.

The men came in the middle of the night. One evening in November 2020, a couple of white-passing men approached a tent nestled by the north side of the church. It belonged to three Indigenous women. The men heaved patio stones onto the tent, quickly piled stacks of flammable material on top, set it on fire and sprinted away. The tent went up in a blaze. A great plume of smoke snaked up in the sky, high over the top of the church.

Watson’s husband, alerted to the flames, rushed to put the fire out, but the damage was done. When Grant arrived on the scene the next day, everything in the tent was burned. Only the charred remains of items like a beach umbrella and pallets remained. There are still blackened scorch marks on the side of the church today.

The young Indigenous woman who was supposed to be staying in the tent alone that night had left before the fire, but she returned to the ashes of her belongings. “She was very scared,” says Grant. “But this is a reality that she lives with.” Indigenous women are disproportionately represented in the unhoused population, and they are also three times more likely than non-Indigenous women to experience violence. “[The men] wouldn’t have known whether somebody was in the tent or not,” Grant says. “It was deliberate.”

When the police arrived, Grant says it took the officers about thirty minutes to determine that they likely could not pursue the case any further. Although police accessed security footage of the event which had been captured by a nearby hotel, Grant told me police didn’t think they could catch the perpetrators using the available information. (A Toronto Police spokesperson confirmed that officers viewed footage of the suspects. However, they said factors like image quality, camera angle obstructions and face coverings may impede the usefulness of the video evidence. An investigator is assigned to the case, which remains open.)

Grant was disappointed with how the police and fire department responded to the incident. Along with other community organizers, they tried to reach out to city officials for help, but felt the matter was once again mostly disregarded. When contacted for this story, both MP Adam Vaughan, who represents Spadina—Fort York, and a spokesperson for Toronto Centre City Councillor Kristyn Wong-Tam, said there was little they could do since the incident falls under police jurisdiction.

But the attack is far from an isolated incident. Backlash against encampment sites has been mounting as Toronto’s unhoused population has become increasingly visible in public parks. According to Simone TB, a volunteer with Encampment Support Network (ESN) who visits encampment sites multiple times per week to deliver food and other basic necessities, tents around the city have faced many forms of violence. “I see harassment from neighbours and the townhomes and people throwing garbage,” she says. “There’s just this anger and lack of understanding from other citizens.”

In March 2020, the city began moving some of the unhoused population inside from encampment sites to a new hotel shelter system, which is comprised of roughly twenty rented hotels spread across Toronto. To make up for limited shelter beds, the city has provided up to three thousand spaces in temporary shelters and hotel programs.

Wong-Tam’s office said one of the reasons for the temporary shelter system is unsafe encampment settings; as of March 15, 2021, there have been at least twenty-seven encampment fires, including at least one death. Given the limited number of city staff available to ensure safety for the roughly seventy-five encampments scattered around Toronto, Wong-Tam’s office said moving almost 1,390 unhoused people inside since April 2020 was a necessary measure.

Grant believes increasing temporary housing was an important achievement, especially during the winter months, but says it also came with certain drawbacks. “As [the hotel shelter system] is governed by the shelter system, there are quite a few zero-tolerance policies,” they say. Shelter residents have reportedly had to leave for reasons like taking the stairs instead of the elevators or having too many bags in their rooms. “We saw a flow between people being updated to housing and then being kicked out and returning back to Trinity Square.”

Watson, who has stayed in a hotel shelter in Scarborough, says she prefers living at Trinity Square instead. “We have the hotel,” she says, “but honestly, it’s like jail.” The hotel shelter system usually separates residents into their own rooms, and being alone for an extended period of time has increased the rate of deaths from drug overdoses in these locations. Wong-Tam’s office noted that in response to the rise in fatal opioid overdoses and shelter-related deaths, the city has invested $7.6 million in harm reduction programs for all shelters.

Even with the new funding for supervised consumption sites in shelter hotels, some policymakers feel the city’s efforts are falling short. Vaughan understands why decision-makers felt compelled to act immediately, but he can see why many people temporarily housed in these settings don’t want to stay there. “The old hotel ten minutes out of town is just like the homeless shelter at the end of the day, especially if you impose harsh rules and regulations, and govern people’s lives and don’t give them freedom,” Vaughan says. “People’s lived experiences [are] being ignored … and what people feel matters.”

For those who decide to remain outside, finding any kind of structure to protect them from the elements can be the thin line drawn between life and death. Khaleel Seivwright, a carpenter, has been creating small refuges across the city with his Toronto Tiny Shelters, structures that are eight feet long and five feet high. He began building them in September 2020 on a volunteer basis, working seven days per week to construct the shelters out of wood, foam and insulation. They’re also fashioned with a carbon monoxide detector, smoke alarm, window and two locks on the door.

In 2017, Seivwright lived outside in a tent in Vancouver. He calls the experience the most challenging part of his life. He can’t imagine how people fare in Toronto temperatures, which is why he meticulously researched the amount of insulation needed to keep people warm. “I was freezing in -10 [degrees],” he says. When people live outside in -15 or -20 degree weather, “they must be wondering if they’re going to wake up dead.”

Watson stayed in one of Seivwright’s tiny shelters installed in Trinity Square last year. “I really enjoyed it,” she says. “My window actually opened.” She went to Dollarama one day and bought string lights and a shaggy carpet, which she glued onto a wall. On the opposite wall, there were pictures of her family and her children. Her time in the tiny shelter came to an end when she temporarily went to stay at the hotel shelter, but she was happy to know the tiny shelter was given to another person in need.

It’s true there have been incidents involving these structures. Watson once saw a distressed man experiencing a mental health episode burn down his tiny home at Trinity Square. City officials used this fire and ones in other encampment sites to justify filing an injunction against Seivwright in February to stop him from building, distributing and installing his shelters across the city. (Seivwright points out that his latest shelters are made with rockwool, an inflammable material.)

The injunction cites bylaws that ban camping and living in city parks. Toronto Fire Services also claims that tiny shelters are unsafe, noting that 2020 saw a 250 percent increase in encampment fires. (Given there is no solid data collected by officials about the number of encampment sites, it’s unclear whether this increase in encampment fires is proportional to the corresponding rise of people in encampment sites overall.)

Following the injunction, community members have come out in support of Seivwright’s tiny shelters. More than five thousand people have donated over $275,000 to Seivwright’s crowdfunding campaign, which was originally meant to fund the purchase of construction materials, but now will help support his legal fees.

Every time Seivwright has asked the city for an official fire safety inspection, he’s been denied. “I think it’s a refusal to, in any way, legitimize these tiny shelters existing and helping people,” he says. Seivwright has ceased building shelters, but he is prepared to pursue a constitutional fight against the city bylaw prohibiting people from staying outside if the case against him isn’t dropped.

Watson describes the city’s actions towards encampments as combative against unhoused people. It’s not just the shelters, she says. The light posts around Trinity Square used to have plugs that people could use to power their heaters or charge phones, until one day city officials came in and covered them up. A spokesperson for the city said that encampment residents’ use of plugs was a safety risk. But for Watson, the city was sending another message. “It’s like we’re not deserving,” she says. “We’re not good enough to have those things.”

Leigh Kern remembers watching the police officers converge on the square. A reverend with TUMN, she has witnessed police raids during which officers run encampment members’ names through their system to check for warrants, even minimal ones from other cities, often leading to arrests. Though this practice predated the pandemic, every time the police returned, Kern says the site was immediately charged with anxiety and fear. “Houseless people experience police intervention every day. It is part of their daily experience being policed and harassed, just for existing in public space,” she says.

Efforts to move people out of encampments extend to government policy as well. In March 2021, the city announced Pathway Inside, a program which aims to relocate residents from the four main encampment sites to the downtown Novotel Toronto Centre hotel. Encampment residents received notices that if they didn’t move to these new shelters by April 6, they would have to leave the parks. The city has leased the hotel—up to 254 rooms—until at least the end of 2021.

Pathway Inside is meant to be a stepping stone for encampment residents to secure permanent, affordable housing. In December 2019, Toronto Mayor John Tory committed $23.4 billion over the next ten years to the cause. The city says 1,248 new affordable units—specifically allocated for people experiencing chronic homelessness—will be available by the end of the year. And in April 2021, the provincial government announced $15.4 million for supportive housing that aids vulnerable communities at risk of homelessness in Toronto.

But many community organizers and encampment residents are wary of the city’s claims. Simone TB, who works with ESN, says programs like these serve to minimize the publicity around homelessness without offering an immediate increase in permanent housing like many encampment residents are calling for. “[The city is] not asking people what they need,” she says. “It’s a rebranding of eviction.” (A spokesperson for Wong-Tam, who supports the program, says city staff visited the four main encampment sites in February 2021, speaking to at least twenty people staying there about their thoughts on Pathway Inside.)

Simone TB believes the city is forcibly removing people from their homes because nearby residents don’t want to see unhoused people in public parks. She says programs like these are silently drawing the veil back over the housing crisis that has plagued Toronto for decades. “It’s taking away the visibility of this crisis that we’re in,” she says. “There’s no humanity in it.”

On April 1, just days before the city planned to begin enforcing encampment evictions, the plan was temporary suspended due to a Covid-19 outbreak inside the Novotel hotel. But by mid-May, the city began taking action. At Lamport Stadium Park, encampment residents received trespass notices, which threatened arrests and fines of up to $10,000 if they didn’t leave the park within the coming days.

On May 19, tensions erupted as dozens of Toronto police officers (some mounted on horseback), city workers and corporate security guards attempted to remove encampment residents from Lamport Stadium. They came with two excavators, hazmat suits and dump trucks in tow. Community members mostly blocked the efforts to clear the encampment, ultimately protecting all but one tent and two wooden shelters.

“Police cracked down on supporters, punching some in the face and dragging others along the ground,” reads a recent statement from ESN. Organizers claim one resident defending a shelter was detained by police after being trampled by several officers, and was eventually released from custody with deep cuts and bruises on his body. According to police, at least two officers sustained minor injuries, and several protesters who did not live at the site were arrested.

Due to the community protests, the attempt to clear Lamport Stadium proved largely unsuccessful. But the city’s open threat to other encampments looms. A city spokesperson confirmed there are more clearings to come. (Another spokesperson stated that the incident at Lamport Stadium was a “general city directive,” which wasn’t related to Pathway Inside.) At the time of publication, Holy Trinity has not yet heard whether its encampment will be targeted, but the possibility casts a shadow over the church.

Crowe, for her part, sees the city’s lack of any definite plan for the shelter system as one of the biggest concerns for Toronto’s unhoused population. She calls the temporary hotel system “a band aid in a pandemic.” For Crowe, there is no question: homelessness can only be solved with massive collective efforts—and providing safe, single-room shelters and permanent housing has to be the priority.

But she also believes we should think even bigger. She wants to see a return to the type of national social housing program that Canada had after the Great Depression. The government committed to subsidized mortgages, granted loans to incentivize housing construction, provided social housing for senior citizens, and more. Crowe realizes there are smaller steps to take first, though. “In the short term, the only way we can fix housing for people is through rent supplements, or housing allowances,” she says.

In the long term, for an issue as intricately complex as homelessness, there needs to be more: More city workers and shelter staff, so they can adequately care for those who are unhoused. More paid sick days and improved social assistance rates, so people can secure and hold on to permanent housing. More aid for children in abusive homes, who have higher chances of developing mental illnesses and becoming unhoused. More support for those experiencing addiction. And fundamentally, more nation-wide acts dedicated to solving homelessness, rather than expecting cities and provinces to do so alone.

Today, the marbles are falling off of the memorial. Whether it’s from the blustery weather or the people who pick them off for themselves, there are now honeycomb-like gaps of clear empty resin shells in the mosaic. The Holy Trinity team hopes to fill the holes, but it’s unclear when that will happen.

Grant remembers questioning the future of the memorial one morning in particular, when they looked out of their office window and noticed several black SUVs in front of the church. They walked out to find Premier Doug Ford observing the memorial, presumably on a break from a meeting in a nearby building.

Grant approached Ford to talk to him about the unhoused population in Toronto. “I told him the memorial is literally collapsing under the weight of all of these names,” they said. “All of these people’s lives have gone, have slipped through our fingers.”

Ford was sympathetic. He told Grant that maybe the province could pay for a wall with all of the names engraved on it, but Grant politely declined. “We live in a state of ongoing conflict. A social conflict that, for the majority of people, is invisible,” they say.

While a wall of names would pay respect to those who have passed away, Grant believes that it would be premature. They liken Ford’s offer to building a war memorial of sorts, but the housing crisis in Toronto is far from over. “We want these folks to be honoured in peacetime,” Grant says, looking at the rows of names on the pages. “We need to end that war first.”

Stephanie Bai is a student at the University of Toronto, where she is currently managing online editor at the Varsity. She frequently contributes to her campus publication, and she has also written for This magazine. Find her on Twitter @stephaniebye_.