Illustration by Graham Roumieu

Illustration by Graham Roumieu

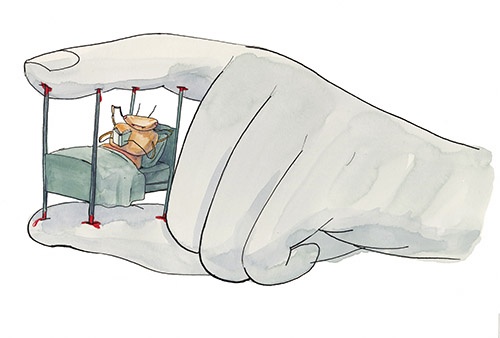

Bugging Out

The industry that fights bed bugs is growing, but the only real winners are the pests themselves.

There is pleasure in pressing a bed bug to death between your fingers. When it expires, there’s a stale stench, like catching a whiff of permanent marker. The bug’s body gives way easily, leaving behind a trace of your own blood.

Most people, if they are lucky, will never have to know the indignity of feeling that familiar itch and reaching down to grab the culprit. Nor what it’s like to spend almost two months waking most nights around 4 AM and taking a quick, numbingly cold shower in order to fall asleep again.

With time, I’ll discover that tucking socks into sweatpants can help keep the bugs away. But in a dry Alberta summer with no air conditioning, it’s too hot for layers. A roommate whose name I never learn goes to the hospital for a few days because she had an allergic reaction to the bug bites. When she comes home, she sleeps on the kitchen floor, double-sided tape surrounding her, a protective fortress.

Sometimes I imagine scenes where I invite a stranger from Grindr over and he plucks an apple-seed-sized intruder off his skin and asks, “What the hell is this?” So, instead of trying for a meetup, I lie in bed alone.

As my other roommate hints that the bugs are spreading across the complex, I wish I could solve the problem myself. But I can’t afford an exterminator. Besides, I leave at the end of summer anyway. I’m living on borrowed time, on borrowed furniture. Our landlord suggests we do our best with some cheap bed bug control products he’s benevolently purchased. He tells us if it gets worse—whatever that means—he’ll take the next step.

For ages, bed bugs were commonplace, their bites a small annoyance of city life—fodder for nursery rhymes, even. Yet by the 1950s, they had largely vanished from North America due to overzealous pesticide use.

Today, bed bugs are back from the brink of extinction, and though they’re not as ubiquitous as they once were, people are no longer as tolerant of them. We expect our living spaces to be free of pests, no matter the cost. We’re not willing to abide being bitten as we sleep. We want bed bugs dead.

The self-described Bed Bug Detective is more P.T. Barnum than Sherlock Holmes. One of Brian Barton’s signature attractions is called “a hide.” He takes a little glass bottle with live bed bugs inside, stows it away and has one of his specially trained dogs—Dottie, Red, Duke, Oliver or Rosie—go find it. It’s a way to teach clients his routine, but also to show them the remarkable skill of his canine co-workers. The severity of the case the dogs ultimately sniff out dictates Barton’s next step in the extermination process: from killing the bugs with a modest steam treatment to raising the property’s temperature with his heat treatment unit for more extreme cases.

To sustain the hides, Barton keeps about one hundred living bed bugs in a dark, warm part of his house, though he’s cagey mentioning specifically where. They reside in an old-fashioned glass fishbowl. “They can only reach halfway up that apex, and when the glass starts to curve back into the upper lid, they just fall down. They cannot hang on,” he says. “For my own peace of mind, I do have a piece of Saran Wrap over top of it, but I don’t need it.” Bed bugs can drive people mad, but mostly Barton feels in control.

The Bed Bug Detective has been in the pest business for about a quarter-century. About a decade ago, he made the switch from working with a large international company to running his own operation in the Halifax suburbs. The business employs his wife and son, and four other workers they took on in 2020 to accommodate more customers. Though Barton’s company tackles multiple pest problems, bed bugs are its bread and butter. And in a coastal city full of constantly moving student tenants and towering apartment complexes, that means big business.

Barton pauses for effect when he speaks, his voice going appropriately high or low to get the message across when he talks about bed bugs—the small, irritating insects that can ingest seven times their weight in blood and take refuge in the tiniest wall fissure or mattress fold. Bed bugs get their name from their tendency toward late night feasts on people fast asleep. The pests can then go without a meal for months thanks to diapause, a hibernation-like condition which slows their metabolism and need for energy.

Because bed bugs are quick to lay eggs and mature, it’s easy for them to proliferate in untreated residences and casually slip through wall cracks or under doors to bother neighbours. Since they can hitch rides on everything from clothing to handbags to discarded furniture, they make their way around urban areas easily, particularly once they’ve established themselves in a multi-unit building.

Growth in international travel is also suspected of supporting the spread of the bug. People aren’t moving around as much during the pandemic, so bed bug numbers have remained relatively stable over the past year. But some experts predict we’ll see cases rise quickly as soon as people start travelling again.

Companies like Barton’s—or Toronto’s Bed Bugs & Beyond, or British Columbia’s Heat-N-Sleep—wouldn’t have existed two decades ago, but bed bugs came back with a vengeance at the turn of the millennium. While there’s little data collected on the pests in Canada, a 2010 study by the National Pest Management Association (NPMA) in the US found an 81 percent increase in bed bug calls to pest management companies over the previous decade. At the time, an NPMA executive said the results “suggest that we are on the threshold of a bed bug pandemic, not just in the United States, but around the world.”

Despite this fact, people still mostly know bed bugs as mythological creatures. They understand that the insects exist and that they bite, but not much else. Eighty-four percent of people making pest control calls have mistaken bed bugs for other pest problems like fleas or cockroaches.

I was no exception. Though I’d heard of bed bugs before, I’d never seen one until they were inhabiting my bedroom five years ago. At first, I assumed I was being bitten by fleas.

In the horror stories we’re used to hearing about bed bugs, they’re usually infiltrating spaces other than residences, travelling along with hosts—human or otherwise—to offices, hospitals, hotels, retail stores and libraries. Yet a recent US market report suggests 43 percent of bed bug treatment calls went to single-family homes and 39 percent to apartments and multi-family housing. A disproportionately large bed bug burden, thus, falls to the little guy.

Bed bugs have created an economic engine over the past two decades. In part, that’s because there’s a clear brand. Mention of the creatures conjures up distinct feelings: a slow scuttle across your skin ending with an itchy bite. Today, bed bugs represent a major component of a nearly $2 billion Canadian pest control industry (about one-tenth the American market). But researchers have also found bed bugs have destroyed wealth, costing billions of dollars globally in treatments and other related costs.

I’ve lived through two infestations—one in the aforementioned subleased townhouse in Alberta’s Bible Belt, which I left before the situation had resolved. The other was in Montreal, in a downtrodden apartment building which eventually caught the attention of city inspectors. That time, I saw the process all the way through.

I read once that, ideally, treating bed bugs involves a team approach with three pillars working together: the landlord, pest control professionals and tenants. Barton agrees with this, though we differ on whether it’s actually possible in practice. “They should all have one common goal, being those bugs gone,” Barton says.

But I think there are other motivations, mostly financial, which jeopardize this shared objective. Pest control professionals need to make money. Landlords have an incentive not to spend it—and considering best extermination practices involve treating several adjacent apartments to kill one known infestation, treatments can cut into their profits big time.

Tenants want a good night’s sleep and not to be bitten, but can be left out of the conversation because of their lack of home ownership. Subletters may be a degree removed from the landlord, and tenants facing barriers due to class, age, disability or language may not understand their rights, or be able to participate fully in the extermination process.

As a working-class tenant with little money or energy to spare, I felt like I was at the bottom of the bed bug economy, powerless against the problem. But I’ve come to learn there are no real winners with bed bugs, except the pests themselves. Their prize is immortality—coming back from the dead to feast and live, and to hold the upper hand against human society in a way most tiny insects would envy.

Early in his pest control career, around the turn of the millennium, Sean Rollo responded to a call from a Vancouver-area youth hostel. Hostel management knew there was a bug problem and that people were being bitten, but not much more. Rollo was in a room full of mismatched metal and wooden bunk beds when he found something he recognized from his entomology classes at the University of British Columbia, but had never before seen in person: a bed bug.

“I think I was probably one of the first people to come across a bed bug job in Canada,” he says. At Orkin, the international company where he’s spent his career to date, nobody seemed to know what to do. Yet two decades later, he’s dealt with too many cases to count.

Pest control experts and researchers have different theories about what exactly led to the bugs’ disappearance and resurgence. Rollo believes our transition away from using spray treatments to kill cockroaches is partially to blame—the treatments also happened to kill bed bugs. But in the 1990s, pest control practitioners switched to bait treatments, which only killed cockroaches. It was an amazing revolution in pest control, Rollo says, but not one without consequences.

Others believe the decline of the toxic pesticide DDT virtually wiped bed bugs out in industrialized nations. There’s a problem with this theory: scientific evidence has shown bed bugs developed resistance to DDT as early as the 1940s, long before it was banned for general use in the US and Canada in 1972.

Regardless of the exact cause, global restrictions on pesticides and increasingly resistant bed bugs mean it’s unlikely they can be wiped off the face of the earth again. Instead, we need to focus on finding the most efficient ways to eradicate them from spaces when there’s a flare up. Or, ideally, we could try to prevent the situation in the first place.

The resurgence of bed bugs has resulted in a flood of new products and services for pest control operators and consumers—from cheap traps and sprays for tenants to professional tools for heat treatments with price tags up to six figures. Yet these treatments aren’t all as effective as they claim to be.

Dini Miller, a professor of entomology at Virginia Tech, says bed bug populations are highly resistant to spray formulation insecticides, particularly those allowed for use indoors. Miller conducted an experiment where she sprayed surfaces, left the spray to dry for forty minutes, then exposed bugs to the surfaces that had been sprayed. The best-performing spray killed just 60 percent of pests after eight days. Regardless, about 80 percent of the pest control industry treats bed bugs with sprays (including the companies my landlords used).

Heat treatment, which involves heating a room to around 150 degrees Fahrenheit, is more effective. Though the option isn’t as well-known by the general public, in British Columbia social housing bed bug “saunas”—heat treatment rooms which blast tenants’ belongings to help curb infestations—have become a standard feature in many buildings. Most of the contents of a single infested room or studio apartment can fit in the sauna. While the tenant’s suite still requires a chemical treatment, the heat rooms allow them to avoid disposing of furniture or personal items, like books and papers, that can’t be chemically treated.

According to a rare estimate of bed bug treatments out of the US, there were 815,000 exterminations between 2015 and 2016, which helped increase treatment revenues by $100 million US over the previous year. One consultant projected that by 2021, killing bed bugs could be a billion-dollar industry.

But Miller says despite the jobs the industry creates, companies don’t necessarily profit. “Sit and look at the room that you’re sitting in right this minute. And imagine that you needed to scrutinize every crack and crevice you can see, every piece of fabric you can see with your eyes, an inch at a time. And think about what that would take.”

The in-person hours required to inspect and treat a space can be costly, particularly if property owners underestimate how much work it will be, which Miller says is often the case. Clients often fail to take into account considerations like the size of a treatment area, the level of clutter present or the density of the infestation, as well as the fact that most jobs need at least a couple of sprays.

Landlords feel the pinch too, which gives them an incentive to put off treatment or to find a bargain option. Surveying apartment managers in her home state of Virginia in 2014, Miller found 50.6 percent of respondents said commercial pest control was the factor which had the most impact on their facilities budget or profitability. This is a notable dent, especially given bed bugs didn’t even have a significant financial impact on landlords’ revenues just fifteen years ago.

Samuel Scarpino, an epidemiology professor at Northeastern University’s College of Science, offers a blunt assessment of who wins in the bed bug economy. “It definitely does seem like mostly just losers,” he says. The losers aren’t just tenants, landlords and small business owners. Bed bugs can also lead to treatment and litigation at hotels and lost productivity at an office suffering an outbreak. Bed bugs have cropped up in hospitals from Halifax to Yellowknife, sometimes leading them to shut down beds, and outbreaks in Ottawa’s ambulance service have made headlines over the past two decades.

Scarpino is surprised there aren’t more coordinated federal programs in countries across the world keeping track and getting ahead of the problem. In Canada, on a national scale, there’s been almost no discussion on the matter. A decade ago, when Ontario spent $5 million to support public education on bed bugs, a couple of MPPs suggested that provincial-level landlord licensing could be effective. That would require annual bed bug inspections for license renewal, and enforce efficient treatments. Since 2017, the city of Toronto has run a licensing program for landlords of multi-residential apartment buildings which mandates that units be pest-free, but a similar program has yet to be introduced on a provincial scale. Instead, bed bugs remain a discussion point of tenants rights’ advocates rather than a fixture of mainstream politicking.

Whatever landlords lose in the fight against bed bugs, it doesn’t compare to tenants. A landlord sees the nightmare from afar. A tenant has to live with it. The losses go beyond financial ones. A bed is a person’s most personal space, a place of comfort, dreams and intimacies. When it’s under siege by bed bugs, it doesn’t feel the same.

Amid rising housing prices and devastating vacancy rates, it’s increasingly impossible for many people to own property in major Canadian cities. Yet tenants’ rights continue to get short shrift and lower-income tenants end up maligned, especially since bed bugs appear more frequently in their homes. Low-rent apartments tend to see constant tenant churn, and research has shown these tenants more habitually take furniture off the street and bring it home, which can lead to outbreaks.

Low-income tenants navigating bed bugs are often in a bind. They can’t afford to move, get treatment done themselves, or take time off work to deal with the problem. Tenants may even choose to toss belongings like furniture or clothing, depending on the infestation’s severity, and bear the cost of replacing them (though this won’t solve the problem and many experts don’t recommend it).

It doesn’t help that bed bug regulations are perplexing to navigate. Generally speaking, it is the tenant’s responsibility to inform the landlord of bed bugs, and the landlord’s responsibility to pay for treatment. In Quebec, if a landlord can prove a tenant brought in the creatures, they can sue to recoup treatment costs. In the comparably litigious United States, websites like Bed Bug Lawyer will connect would-be plaintiffs like bite-suffering tenants or hotel guests with a local lawyer.

In Canada, however, these kinds of landlord-tenant disputes mainly play out in the legal aid system. Ali Naraghi, a former staff lawyer at Hamilton Community Legal Clinic, estimates about 40 percent of the calls his office received from low-income tenants were bed bug-related. His clinic also represented twelve Syrian refugee families who left a Hamilton highrise in 2016 after failed bed bug treatments.

I presented Naraghi with a suspicion based on my own experiences: that there’s a bare minimum of treatment landlords can complete and still meet regulations, an amount which is enough to avoid litigation or other consequences, yet falls short of solving the problem. He says, in Ontario at least, as long as landlords are doing some kind of treatment, there is some room for interpretation in the regulations which require them to proceed with treatment once informed, at their cost. “The fact that the treatments are not effective is not addressed by the Residential Tenancies Act,” he says. “And I think that’s the gap that needs to be filled by policymakers.”

There is a certain reliance on benevolence in the bed bug economy. It’s expected of non-profit tenants’ agencies, legal aid lawyers, and people like Barton, who—while part showman and part detective—also must be part social worker. People with low incomes, mental health issues, or differences in ability or migrant status may be unable, for a variety of reasons, to navigate the hoops one has to jump through to deal with the problem. The elderly, or some people with disabilities, may not recognize symptoms, be able to prepare their homes for treatment, or be able to move during a protracted outbreak. In the end, it comes down to tenant self-advocacy, which not everyone is able to engage in.

This was the case with most of us living in my former apartment building in Montreal’s Rosemont neighbourhood. Living in a building that didn’t require a credit check or references, we weren’t people with a surfeit of time and inclination for uprisings. Over the course of a few months, the building became littered with flyers from a community tenants’ organization encouraging us to band together and fight back against our landlord. I never engaged, but remain thankful to those who did.

Four months after I moved in, city inspectors checked our apartments for bed bugs and four weeks later, as spring started to unfold, we were informed of an upcoming treatment. The first one didn’t take, though, and we’d go on to have more spray treatments through late fall.

I worked as a barista at the time and to prepare for an early morning spray treatment, wearily tore my apartment apart after getting home from a closing shift more than once. Pulling out drawers. Tightly bagging items. Moving furniture away from the walls. I even had to busy myself away from my apartment while treatment occurred on my day off until I was permitted to re-enter several hours later.

People living in places with bed bugs are required to keep possessions like clothing and linens in bags until they can be laundered. Other items need to be safely removed and inspected. If there are pets, they need to come with the tenant when the premises are vacated, though fish can stay put if their tank is covered to prevent the spray getting in. These expectations take a lot of time and energy, especially in a multi-person household. One Toronto pest control website goes as far as suggesting residents “consider wrapping books and storing them for eighteen months as books are a nice home for bed bugs.”

One of the biggest consequences can’t be measured with dollars and cents: the mental health aspect. In Alberta, I felt delusional and disoriented all summer from my constant lack of a full night’s sleep. For a long time after moving, I swore I felt bed bugs crawling on me, even though it was all in my mind. The stigma was a heavy weight to bear. Talking about the problem with people who’ve never experienced it can be embarrassing, and not being able to have guests over can be isolating.

In Montreal, when the first bed bug appeared, I met it with quiet resignation and no illusions that the infestation would end quickly. And it didn’t. During the year and a half I lived in the building I went through two cycles of bed bugs.

In one documented case, at another Montreal apartment building, an unrelenting bed bug infestation led a woman to die by suicide. “Ms. A.” as she was identified, had dealt with mental health issues for many years, but the infestation caused her unbearable distress. “I cannot stand to live in fear of me being eaten alive,” she wrote in an email to a friend before jumping off her seventeenth floor balcony.

The bugs are uniquely distressing: Barton remembers one case like something from a Stephen King novel, where at 3 PM, an apartment’s carpet and countertops were obscured with bed bugs. For several months afterwards, he thought about the scene when he’d go to sleep in his own house. “There are people that are struggling every day, and it breaks my heart sometimes,” Barton says, his voice breaking.

Barton believes mitigating the problem doesn’t have to be expensive. Landlords could require new residents to put a cover on their mattress and box spring to trap bed bugs inside, allowing them to discover the problem early on. They could also help tenants vacuum and seal up cracks and crevices around the space, if for no other reason than to save fumigation costs later. These strategies aren’t foolproof, but they’re a start.

I’m empathetic to people who have experienced bed bugs because I’ve gone through it. Landlords and policymakers shouldn’t have to live with an outbreak themselves in order to understand that regulations need to change. That said, a bed bug outbreak at Rideau Cottage or a premier’s home would certainly prompt some soul-searching.

One of the strangest things about bed bugs is you won’t know the last time you’ve been bitten, or when you find the last one. One day, if the treatments hold and the stars align, they will disappear. In time, you won’t frantically pat yourself down because a fold in the sheets or a crumb gives you a flashback.

For me, a more permanent effect of surviving the bugs has been the end of believing that even as a renter, I still control what happens inside my apartment. I now know that there’s a threshold of suffering your landlord will expect you to endure. Knowing that tenants were being bitten wasn’t enough to make my landlords hop into action. Not enough to make them say “you matter, and I’ll fix this for you.” There was a financial cost to put on my feelings of security and sanity. And finally, when the debt was paid, I received a hasty spray treatment in my apartment—a method that can amount to little more than a gamble.

When Barton gave chemical treatments to an apartment, it took about thirty to forty minutes, depending on prep and size. But he found that pushed the bed bugs around. “You would go and treat one unit; they would run to the apartment next door. I swear in one particular place I chased them over, up, back and then down to where they originated.”

Treating bed bugs presents an opportunity for risk-taking. The most sure-fire methods take more money and time, but if you feel lucky, maybe—just maybe—a cheaper spray treatment will hit the bugs just right and the problem may end.

This illusion of progress can perhaps buy you a few nights of restful sleep while the bed bugs sit back and wait in some lonely crack or crevice untouched. They can be patient. Their moment will come again, whenever they decide it’s time.

Rob Csernyik is a journalist and writer currently based in Saint John, NB. He is an MFA in creative nonfiction student at the University of King’s College. He edits Great Canadian Longform, and has written for Canadian Geographic, the Globe and Mail, the Narwhal and Vice.