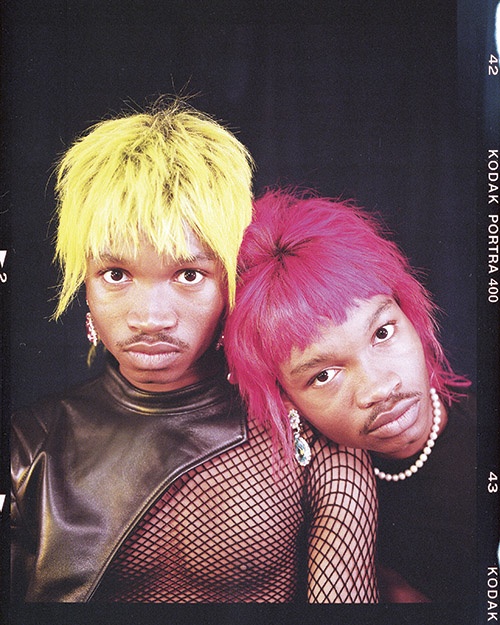

Jorian Charlton. Untitled (Whak & Mo 2), 2020.

Images courtesy of the artist and the Art Gallery of Ontario.

Jorian Charlton. Untitled (Whak & Mo 2), 2020.

Images courtesy of the artist and the Art Gallery of Ontario.

Out of Many

Sharine Taylor reviews photographer Jorian Charlton's first solo exhibition.

For many Black people, the archive can be a hostile site. As Black feminist thinker Saidiya Hartman writes in her essay “Venus in Two Acts,” archives are limited in their ability to document Black life. Despite there being almost no firsthand account of Black women’s journeys through the trans-Atlantic slave trade, the untenable violence inflicted on their bodies is present in archival texts.

Tina Campt, another Black feminist thinker and a theorist of visual culture and contemporary arts, has suggested a way to approach this gap: pay attention to images. Campt’s research explores how we might listen deeply to photographs to engage with historically ignored subjects and members of the Black diaspora. Her academic work shares their stories to expand upon the ways we know and understand Black life.

Toronto-based photographer Jorian Charlton is building on this work of restoring and reimagining how Black life is portrayed. She uses the archive as a springboard into conversations about the act of remembering, diasporic identity, reframing immigration and Black subjectivity.

The story of Charlton’s latest series begins with her father. In 2017, Clayton Charlton nonchalantly handed his daughter a collection of 35mm slides that he had taken between the late 1970s and 1980s. Though he didn’t consider himself a photographer, he’d spent a great deal of his time chronicling his family’s life in Jamaica, New York and Toronto. He photographed them socializing and relaxing, the interiors of their homes and the details of their neighbourhoods. The images are joyous and full of life—people dance in living rooms, cut coconuts in lush fields of green grass and laugh over cold beers on the beach.

After tucking her father’s slides away for safekeeping, Charlton found them a few years later while cleaning out storage. She decided to engage with them in her own practice. Using her father’s images as a frame of reference, Charlton invited her friends and peers to join her in creating an intimate series of portraits inspired by the family album.

In 2021, she launched her digital exhibit Out of Many, which displayed her own photographs exploring Black aesthetics and Jamaican-Canadian identity alongside her father’s slides. She showcased her father’s images by hanging some of them on the walls of a virtual living room and projecting others on a TV in the same space. The digital room is a replica of the insides of many Caribbean homes, with a sound system and vinyls of classic reggae albums, a couch covered in plastic and doilies lining the furniture.

Following the success of the online exhibition, Out of Many has been recreated in person at the Art Gallery of Ontario, and is on display until August 2022. Both the virtual and physical exhibitions of Out of Many make a personal history public through the act of remembering. Family albums are home to intimate visual histories and stories of the people with whom we share, and have shared, kinship. Charlton’s work redefines the contemporary family by using close friends and acquaintances as its subjects, and reminds us of the comfort and community that family bonds can provide us.

While there are no explicit indicators of the precise relationships between her subjects, her photographs tell a more textured story of the expansiveness of family—whether it’s defined as a chosen group of people, a blood connection, or a bond formed through geographical proximity.

For Black families, the album makes up for what the archive, as we know it, lacks. It is an opportunity to chronicle Black life with care so that remembering becomes an intentional process. The subjects in Charlton’s exhibit stare into the lens with a clear awareness of how they appear in the images being made. The Black family unit, in all of its varied forms, positions itself as deserving to be documented and remembered in whatever manner its members see fit.

The Jamaican saying “every mickle mek a muckle” loosely translates to “many small things contribute to making something bigger.” The DIY spirit is a true testament to Black expression and a way of living known to many working-class people in the Caribbean. Charlton, who is a second generation Jamaican-Canadian, leaned into her heritage and this spirit to inform the environments her subjects appeared in.

She staged her photographs inside of their homes, or repurposed areas in her own home, in order to create a sense of familiarity. This approach allows her subjects to mark and claim their place within Canada, creating a space of belonging for many Black Caribbean people of the diaspora who find themselves suspended within the liminal boundaries of not being quite from there or quite from here.

Charlton takes cues from the work of American photographer Deana Lawson, whose images show the beauty of Black aesthetics and bodies. Lawson’s portraiture is known for chronicling Black people and Black life in a way that straddles truth and fiction. Her highly stylized portraits show Black people comfortably and confidently posing in domestic and public spaces.

Like Lawson’s, Charlton’s work is intimate without veering into voyeurism. In Untitled (Shai & Lex), she documents a tender embrace between two people on top of a kitchen counter. In Untitled (Nyali & Nyromi), she shares a gentle moment between two young children in pink bathing suits holding hands.

Sometimes, her subjects’ poses become acts of cultural retention. In the portrait Untitled (Sydné & Keverine), two subjects squat with their backs to the camera, a clear reference to the 2007 single “Chat To Mi Back” by Jamaican dancehall artist Lady Saw. Maximalism in all of its forms is encouraged in dancehall: in the music, the lyrics, the dancing and especially the fashion.

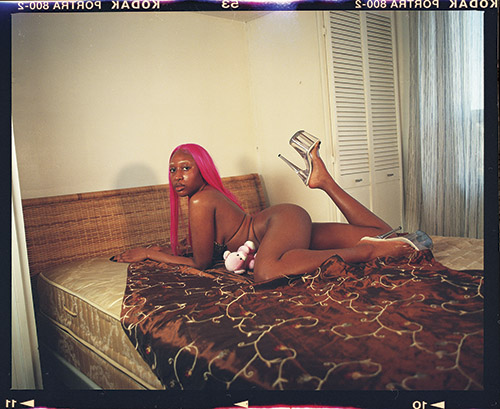

Charlton’s portraits carry dancehall’s legacy across borders by showing members of the diaspora expressing themselves through vibrant colours and loud textures. The subject of Untitled (Miki) rests nearly naked on a bed, wearing dramatically tall, clear platform heels and long pink hair. In Untitled (Whak & Mo 2), identical twins pose for the camera in black leather tops with fishnet cutouts and neon pink and yellow wigs.

By centring kinship, beauty and assured self-expression, Charlton disrupts a visual logic that seeks to position Black immigrants as exclusively occupying roles of servitude. Many of the Jamaicans who have come to Canada have done so in hopes of better economic opportunities. In the post-independence era, Jamaican immigration to Canada was partly shaped by gendered and racialized policies like the 1955-1967 West Indian Domestic Scheme, which offered single women from the Caribbean landed immigrant status upon completion of one year of domestic labour.

If photographed at all, Black Caribbean immigrants were seen through the lens of subjugation, mainly documented as domestic or agricultural workers. We rarely learned these people’s names, and little information was shared about who they were beyond how they acted in service of their host country.

Albeit for different reasons, Charlton also had trouble confirming the names of many people in her father’s photos (though he was able to remember more of their stories after he saw them on display in the exhibition). She honours these histories by leaving the photographs in Out of Many untitled, followed by the names of their subjects in parentheses. Her approach marks a shift in the practice of Black archiving—allowing her subjects to be introduced and known on their own terms.

There’s a grim reality to contend with when we think about how Black Caribbean culture will be remembered in Toronto. As neighbourhoods like Little Jamaica feel the effects of gentrification, active documentation and preservation of our culture takes on new urgency. Charlton’s work is a tangible reminder of the Black Caribbean people who have migrated to the city, called it their home and brought with them the cultures of the places they hail from.

Charlton’s exhibition takes its name from Jamaica’s national motto, “Out of Many, One People.” Though the motto has a variety of interpretations, its evocation here reminds us that out of many kinds of archives that may prevail, Out of Many is just one way these stories can materialize.

Where Hartman asks us to consider what has been lost in the archives and Campt asks us to listen to the images that we do have access to, Jorian Charlton offers a response: the family photo album is a site for remembering our histories and creating new ones. Here, Black expression is validated, Black aesthetics are celebrated and Black life can finally be archived with agency. ⁂

Sharine Taylor is an award-winning music and culture writer and filmmaker. Her passion for writing, archiving, creating and curating has informed her approach to documenting the expansive cultural production that takes place in the Caribbean, and how it materializes and transforms in different spaces.