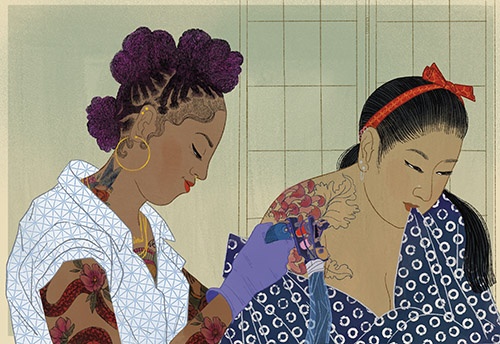

Illustration by Salini Perera

Illustration by Salini Perera

Inking Inclusion

For many queer, trans and racialized people, tattoos are more than skin deep.

I have been fascinated by Coraline’s titular prepubescent heroine since I first heard about her in seventh grade. The Neil Gaiman novella, illustrated by Dave McKean, traces the journey of a neglected only child who wanders through a corridor in her new house into a dangerous but intriguing parallel universe. In the Other World, as it’s called, everything is better: Coraline’s parents actually care about her, she makes a friend, she sees singing rats and she eats delicacies that many children would envy. But here’s the catch—everyone in the Other World has buttons for eyes, and Coraline’s loving but secretly malevolent Other Parents want to sew a pair on her, too. While some might be spooked by the idea of entering a seemingly ideal but increasingly strange alternate universe, I was fascinated by what such a portal might offer.

I encountered Coraline again in a gothic children’s literature class in university. I loved everything about it, from the uncanny illustrations to the idea of a girl observing, navigating and challenging her worlds alone. Something about Coraline exuded the sort of wilful courage and boundless curiosity I had always wanted to have. So, two years ago, I decided to make my friendship with her a bit more permanent; through a tattoo. I had a specific poster from the 2009 stop-motion film adaptation in mind: an image of Coraline and the neighbourhood black cat looking down the hallway that connects their world to the Other World. I wanted a cartoonish, childlike design that would capture Coraline’s wonder and fear. It had to be dark, but with fine lining to capture the minute details of the picture, and room for colour to really bring out Coraline’s purple-blue hair.

This wasn’t my first tattoo. My first two had been done in traditional walk-in tattoo shops, by white dudes with no interest in friendly conversation. The routine felt pretty cookie-cutter: the artist would shave and clean the spot to be inked, the needle would buzz, the newly tattooed skin would be cleaned and wrapped and I’d pay and leave. I would have liked to learn more about the artists: the intricacies of their unique styles, why they chose to work at their specific shops or how my design fit into their larger bodies of work. Instead, it felt awkward to have them working so intimately on my skin without really seeming to care about who and how I was. For me, and many queer, trans and racialized people, getting a tattoo can be a deeply vulnerable act. It can be difficult to get inked when the industry has historically been dominated by straight white men who might not understand this specific vulnerability.

For my Coraline tattoo, I decided to make an appointment with Shanice Bishop, an independent Black artist in Vancouver who’d tattooed me once before. Bishop works out of a cozy nook in Chinatown, tucked away in one of many older buildings in the area that house private tattoo studios. The space is filled with Bishop’s designs and stencils, most of which feature her typical dark linework and are inspired by fantasy characters and human bodies. The studio exudes a chill, relaxing vibe, homey and intimate, unlike the busy communal atmosphere of traditional tattoo parlours.

Bishop was the first queer woman of colour I’d ever been tattooed by. We had an immediate bond. When Bishop tattoos me, we discuss shared experiences, such as unconventional career choices and living and working in gentrified neighbourhoods. We chat about her photography projects, clients she’s been inking and the styles she’s been working in. There’s a natural flow to the conversation and I feel at ease in her space.

While getting a tattoo might seem like a frivolous venture, for some LGBTQ2S+ and racialized people, it’s a way to reclaim our bodies and defy the social norms that limit the expression of our identities. Studios run by artists who are queer and trans people and BIPOC (Black and Indigenous people and people of colour) can even become spaces of community care. Through consent-focused practices and measures to increase affordability, these studios are often a way for queer, trans and racialized people to carve out space in an exclusive industry and take care of each other.

Tattooing is endemic to many cultures across the world, including many Indigenous communities across North America. Despite this, the industry continues to be dominated by cisgender white men. According to job search platform Zippia, in the United States an estimated 75 percent of all tattoo artists are men, more than half are white and only 6 percent are part of the LGBTQ2S+ community. While such data is missing for a Canadian context, many queer, trans and BIPOC tattoo artists have spoken out about sexism, racism and exclusion in the industry. This discrimination can create a barrier to entry, especially in a field that relies heavily on mentorship and networking. Rather than taking the traditional route of apprenticeships—which can be gatekept from queer, trans and BIPOC artists or require them to put up with discrimination in white-male-dominated shops—many marginalized emerging artists teach themselves to tattoo. Vancouver-based queer artist Vin Che started by doing their own tattoos a few years ago, when most tattoo spaces weren’t taking clients due to the Covid-19 pandemic and the practicing artists Che did find were too pricey for their budget. Che eventually left their corporate job and started working at a private studio with a few other queer and self-taught artists.

The lack of diversity in the tattooing industry also shapes the experiences of clients of colour. In a 2023 article for the Walrus, journalist Sherlyn Assam notes that many tattoo shops’ portfolios only feature work done on white or fair skin. This makes it difficult for people with melanated skin to feel represented, or to even imagine what certain types of linework, shading or ink might look like on them. Vaishnavi Panchanadam, a researcher in Ottawa, remembers when she approached a Vancouver-based woman artist of colour for a tattoo. The artist told Panchanadam that it was her first time tattooing skin of Panchanadam’s shade. “I really liked the honesty, because a lot of white artists probably haven’t tattooed on dark skin either, but they don’t tell you that,” she says. “They don’t tell you how the ink might react to your skin, or how it might work with the porosity.” Panchanadam’s previous experience with a white artist at a traditional tattoo shop paled in comparison to how easy it was to relax with an artist of a shared background.

The colour of your skin can make a big difference while getting tattooed. Shades of ink can show up differently depending on your skin tone. If an artist is unfamiliar with inking darker skin, they might push the needle too deep and cause a blowout, in which excess ink seeps out and gives the tattoo a blotchy, smudged appearance. In some cases, this overworking of the needle can create raised scars called keloids. These issues can often be avoided if artists are trained in colour theory and experienced with tattooing clients with darker skin.

But even before clients are under the needle, the intense, impersonal atmosphere of classic tattoo parlours can be off-putting. Six years ago, I walked into a tattoo shop in my birth city of New Delhi and got tattooed by a Russian dude who was working his way through shops in Asia. We didn’t speak a lot, and what I remember from the experience is that it didn’t hurt much, it was over quickly and it was nice to have my cousin there because I was pretty bored from the dry conversation. Several tattoos later, I’ve started going to independent queer, trans and BIPOC-run studios that feel far more personal. I don’t feel nervous anticipation or worry about whether I’ll be relaxed enough during the appointment. I’ll often get to lay there for hours and hear about someone else’s life. I’ve spoken with artists about their first tattoos, about how their friends encouraged them to do their first stick-and-poke designs (tattoos that are done without machines) and even about how my family finds it ridiculous that I’d like to build a patchwork tattoo sleeve, composed of many different designs. For folks from marginalized backgrounds, this genuine connection and relationship-building can offer a much more holistic experience than the sterile nature of traditional tattoo parlours.

In Canada, what has historically been an industry dominated by white settlers seems to be branching out in who it opens its doors to. Queer, trans and BIPOC artists are increasingly creating their own private studios. While these spaces might be smaller and managed entirely by a few in-house artists, they offer a kind of community connection that queer, trans and racialized people can struggle to find in traditional tattoo shops. A kinship emerges in these studios: the relationship between the artist and the client becomes an opportunity to learn, connect and converse about shared cultural backgrounds and the systemic barriers that affect the accessibility and affordability of tattoos.

In my quest to speak with queer, trans and BIPOC tattooers across Canada I found Kae, who operates out of Catalpa Studio in Montreal. Specializing in botanical and queer erotic designs, Kae is passionate about creating a consent-focused and trauma-informed practice. They offer accommodations to address clients’ needs and provide people with the space and time to take breaks if they need to. “I am tattooing people’s bodies from start to finish, so I’m really careful to talk them through every step of the way,” says Kae.

Artists are also working to make tattoos more financially accessible for LGBTQ2S+ and racialized people. For most of my life in Vancouver, I’ve been a broke college student trying to get a piece inked without having to spend most of my part-time wages on it. With rates at some tattoo shops being well over $150 per hour, finding independent artists with budget-friendly pricing has been crucial. It’s an experience that many queer, trans and BIPOC people can relate to, as these communities are disproportionately affected by economic hardship.

Cassandra Faire, a trans artist working in Victoria, B.C., is hoping to make tattoos more affordable for marginalized people. She and her wife co-own Famiglia Tattoo’s Victoria location, where Faire uses her background in fine art to create tattoos that play with darkness and depth, approaching realism while exuding personality. Faire offers all of her tattoos on a sliding scale, and clients are asked to choose a rate based on their level of privilege. By focusing on making tattoos accessible to racialized and queer communities, Faire hopes her clients can feel more at home in their bodies. “It feels so important for people who are trying to feel in control of their own experience and how the world sees them,” she says.

Managing solely on a sliding scale can be challenging in this economy. Faire says that as long as her more privileged clients can pay higher rates, things look good for the most part. If a client can’t afford a higher rate, Faire reasons that they will tell their friends about her practice. “It feels like the impact is bigger and broader and more positive than if I was only working with a privileged client base,” she says.

In many queer, trans and BIPOC-run studios, sliding scale pricing reflects a collaborative approach that opens tattooing up to more people. It’s actually the only way I’ve been able to have as many tattoos as I do. Some artists will also occasionally do trades, where a client can give the artist a tattoo or a piece of artwork they’ve created instead of paying with money. These measures centre reciprocity between the client and the artist and make the experience of getting a tattoo a more mutually supportive exchange.

Community connections are especially important in strengthening the relationships between queer, trans and BIPOC clients and tattoo artists. Many of the artists I’ve visited over the years have been folks whose names came up in my circles: upon hearing a friend or coworker share their experience with an artist, I’d search them up on Instagram, dive into their work and see if I could book a spot. Word of mouth is not only important as a way for artists to gain exposure, but for clients to be able to enter studios knowing and trusting that someone in their community has been treated kindly and with care in that space.

Forging a new path within the traditionally cisgender and white-dominated tattoo trade, studios that prioritize queer, trans and BIPOC artists and clients are emblematic of a shift in the industry. It’s heartening to see a growing awareness of the socioeconomic inequities that prevent queer, trans and racialized folks from pursuing and collecting art they love. But what makes me happiest is how tattoo culture is increasingly becoming a consent-driven practice that empowers marginalized people to feel beautiful in their bodies. It is meaningful and affirming to be able to shape your appearance to reflect how you see yourself, and to celebrate your existence despite society’s rigid and restrictive narratives about LGBTQ2S+ and racialized people. Tattooing can be an act of body liberation and a practice in queer, trans and BIPOC joy.

“It’s so important that people of colour and queer people have access to getting tattoos, especially because these communities potentially have childhoods where they’ve been told to simmer down with how they appear to the world,” says Bishop. Many young queer, trans and BIPOC folks are expected to prioritize employability and change their appearances in order to be palatable. This often means keeping your head down and presenting yourself in a socially desirable way. Getting a tattoo is a means of rejecting these traditional notions of respectability and taking ownership of your body. It’s a radical way to centre your autonomy—choosing art that resonates with you to be stencilled onto your body, in the face of beauty standards, gender norms and the other social constructs that marginalize LGBTQ2S+ and racialized people.

As an Indian raised in the Middle East and now living in North America, I feel like I have been everywhere and nowhere at once. The only constant place of habitation is my body, which continues to carry me through various locations and time zones. It is special to be able to connect with tattoo artists who are also diaspora members and who can relate to this journey.

I began writing this story on a cold winter morning in New Delhi. I had an appointment with Shreya Josh, an Indian tattoo artist who has hosted workshops for emerging tattooers and sold DIY kits for people to do their own stick-and-poke tattoos. I hadn’t even met Josh, but I already felt like I could trust her. Her whimsical illustrative style reminded me of children’s storybooks, and I loved her use of bright colours on melanated skin. Her portfolio shone with beautiful pieces done on skin that we’d describe as “wheatish ” in India—a skin tone just like mine. I’d been waiting for years to get a tattoo from Josh, and it would be my first time being inked by a South Asian woman.

Josh called me into her studio in the afternoon so we could spend some time nailing down the piece. I hadn’t finalized a design yet, but I was hoping to get a splash with different colours to fill in the gaps in my patchwork sleeve. Josh assured me that we wouldn’t rush through the stencilling: “It’ll be on your body forever, so you want to be sure, right?” ⁂

Shanai Tanwar is a freelance journalist and poet of Indian origin living and working on stolen Musqueam land. Shanai’s writing has appeared in Broadview, Chatelaine, the Ubyssey, Cosmopolitan and Harper’s Bazaar. Currently, she proofreads for the Ex-Puritan and enjoys admiring dogs while learning she might secretly be a cat person.