Illustration by Justine Wong

Illustration by Justine Wong

Bitter Roots

Guyana’s festive national dish is a marvel of Indigenous knowledge and heritage.

My paternal grandmother was always a mystery to me. One day, long before her mind had become lost in itself and her body had forgone its willingness to obey her, I asked to interview her about her life. But Granny, in her sharp-tongued way, shut me down immediately. “I don’t like to talk about my business,” she said, and that was that. She wasn’t fond of sharing about herself, the way she grew up or messy things like emotions. For Trinidadians of that generation, and perhaps Caribbean elders in general, there are certain parts of life that simply aren’t talked about—at least not with family. By the time my grandmother passed away last June, well into her nineties, she hadn’t had a firm grasp on her memories for a few years. Dorothy Johnson née Picou, whom we knew as Granny Dot but whose Chinese family would have called Tama at home, was cremated along with many of her secrets. The ones she guarded most fiercely involved what she did in the kitchen.

It was a joke in our family that if we were to ask my grandmother for the recipe to one of her specialty dishes, she would always say, “whatever you have around.” She was a prolific cook for as long as her hands allowed her to be. My father recalls how their house had the typical fare found in many Caribbean households: cheesy squares of macaroni pie, bowls of peppery Trini-style curry and scoops of deep green callaloo bush (taro leaves) cooked and ladled over rice or made into soup. There was the Trinidadian favourite, pelau, a savoury one-pot dish with rice and pigeon peas mixed with browned chicken or beef. But my grandmother also ventured into a range of international cuisines that would have been unusual to find in Trinidadian homes at the time. She made paella, pizza and fluffy clouds of Yorkshire pudding; she slow-cooked Italian chicken cacciatore with a rich red vegetable sauce and simmered French bouillabaisse, a brothy seafood stew. Of course, there was traditional Chinese food in her repertoire as well. Her dining table was where I was introduced to many of my ancestors’ foods that I often couldn’t find in local Chinese restaurants, which usually offered a fixed set of dishes preferred by their Caribbean customers, like fried rice and lemon chicken. I still dream about my grandmother’s egg foo young, a savoury Cantonese omelette filled with delicious meat and veggies and slathered with a soy-sauce-based gravy.

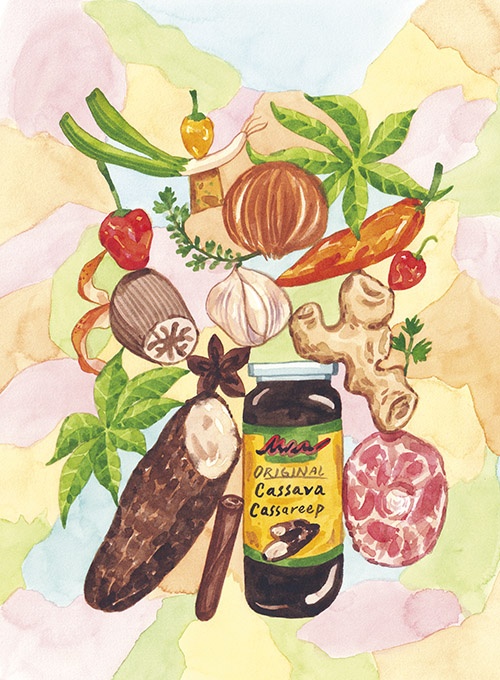

The most exciting dish to smell bubbling in her tiny kitchen was pepperpot, a hearty meat stew that originated in Guyana. Pepperpot owes its unique flavour to the presence of cassava, a starchy vegetable that is a staple in Caribbean cuisine. It appears in the dish in the form of cassareep, a thick, dark sauce with incredible preservative qualities. My grandmother would take various meats, often beef, pork or hardier cuts like oxtail, pigtail or cow heel, and marinate them overnight in cassareep with other seasonings. The ingredients would then be cooked on low heat for several hours in a gigantic pot. In Guyana, pepperpot is traditionally eaten with homemade plaited bread on Christmas morning; in my grandmother’s Chinese household, it was served with rice.

As I reflect on the legacy my grandmother left behind, I think of all the things she didn’t talk about, and yet how her story could be pieced together through the meals she shared with her family. As a Caribbean person with roots in Africa, India, China and Europe, my sense of identity has always been complex. In many of these cultures, my ancestors used oral history to pass down knowledge for survival, but much of that knowledge has been erased by the still-ongoing colonial project. Our food tells stories of how we survived by holding on to the memories of where we came from. From Granny’s pepperpot, I can trace the trajectory of my Chinese family’s journey through the Caribbean. Pepperpot has even more to teach than that: about how Indigenous food and culture have enriched this region, and how our collective generational knowledge can guide us toward a better future for the islands.

Pepperpot is not traditionally part of Trinidadian cuisine. My father suggests that my grandmother learned about it through her immigrant mother Leonora, who was affectionately known as Lenny. Lenny also had a Chinese name she used at home, but it has been lost to history. As my uncle put it to me, “she didn’t want to emphasize her Chinese-ness to us.” Like many of the people who found their way to this country, Lenny and her daughter Dot were expected to discard much of their own culture and heritage in order to survive colonial rule, which has been a deep wound across the back of our history. But even as Lenny and Dot buried parts of themselves, they left breadcrumbs with which we can trace the paths we came from.

The First Peoples of Trinidad and Tobago migrated from the South American mainland about six thousand years ago. Trinidad, being the southernmost island in the Caribbean Sea, was a trading point for different Indigenous groups from up the archipelago and down in South America. Among many other cultural items, they brought with them their cuisines and culinary ingredients—including the versatile cassava.

Indigenous communities still remain in Trinidad today, like the Santa Rosa First Peoples Community in Arima, a town in the northern portion of the island. But after the arrival of Christopher Columbus in 1498, waves of colonists—first the Spanish, then the British, as well as a large number of French migrants—decimated the Indigenous population and turned the vast forested lands into blocks of plantations that would produce raw sugar and cocoa for export. As European countries hungrily scrambled to take control of the Americas and Indigenous populations dwindled, the colonists turned to another labour source that would forever change the landscape of the Caribbean: the transatlantic slave trade. In his 1944 book Capitalism and Slavery, Eric Williams, a historian and the first prime minister of Trinidad and Tobago, writes: “The Negro, too, was to have his place, though he did not ask for it: it was the broiling sun of the sugar, tobacco and cotton plantations of the New World.” The enslavement of African people would become one of the defining traumas of Trinidad and Tobago’s society.

The never-ending hunger of the colonial machine did not falter even with the full abolition of slavery in Britain’s Caribbean colonies in 1838. Without an enslaved African population working in the fields, the colonizers sought to exploit another foreign labour force; this time under the system of indentureship, through which immigrants would be contracted to work on plantations for years. Indian immigrants, like my mother’s family, and Chinese immigrants, like Lenny’s mother, brought yet another rich blend of cultures to the fabric of the region’s tapestry. According to my father, like many Chinese newcomers to the Caribbean at the beginning of the 1900s, Lenny’s mother, my great-great-grandmother, landed first in Guyana before making her way to Trinidad. With baby Lenny in tow, she moved into a place on Charlotte Street in the heart of Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago’s capital, in what is now known as Chinatown. Perhaps she brought with her the pepperpot recipe that her daughter would one day share with her island-born family.

While Trinidad and Tobago gained independence from Britain in 1962, the remnants of colonial rule still have a grip on the country. Over centuries, we internalized the idea that anything we created was not as meaningful as the European culture we were expected to assimilate into. This Eurocentric perspective is still pervasive today, even in our understanding of which foods are valuable. French and Italian cuisines, for example, are often considered to be the heights of culinary excellence in the Caribbean. But a place that serves our own Creole cuisine tends to be a more casual dining space.

In her essay “The Intersections of ‘Guyanese Food’ and Constructions of Gender, Race, and Nationhood,” anthropologist Gillian Richards-Greaves speaks to the nature of food as more than sustenance. “Food signifies who we are or who we perceive ourselves to be,” she writes. In a post-colonial society, part of healing our relationship to identity is unlearning the idea that our culture and our foods are inferior. Pepperpot, the national dish of Guyana, presents an opportunity for this reframing. It is a shining example of how our ancestors in the Caribbean utilized the land around them to create nourishing meals from unexpected ingredients.

The centrepiece of pepperpot is the sturdy root vegetable called bitter cassava. Compared to its sibling sweet cassava, it contains higher levels of cyanogenic glycosides—compounds that can cause cyanide poisoning when consumed in high doses. But the Indigenous peoples of the Caribbean developed an elegant refining process to make bitter cassava edible, through a technique that has been used to make the cooking staple cassareep for thousands of years.

Immaculata Casimero—an Indigenous rights activist and member of the Wapichan Nation who lives in the village of Aishalton in southern Guyana—describes to me how bitter cassava is traditionally made into cassareep. After the cassava roots are dug out of the ground, there is a laborious process of peeling, washing and grating that is often a community effort. Then, the cassava is stuffed into a matapi, a long woven tube with a loop at each end. Once full, the matapi is hung high up and its bottom loop is fit around a pole, on which someone sits to squeeze the juice out from the cassava. The pulp doesn’t go to waste—it can be dried in the sun and made into bread. The juice is strained and boiled in a pot to remove the bitter cassava’s poisonous properties. Once it reduces to a black-brown syrupy liquid, the cassareep is ready to be used in a variety of dishes, the most famous of them being pepperpot.

The use of cassareep allows pepperpot to last for extended periods without refrigeration; additional meats can even be added to the pot later on. The dish just needs to be reheated to boiling temperature daily to prevent spoilage. Casimero tells me that in the Wapichan Nation, cassareep is more frequently used to lightly flavour fish and meat dishes, unlike how it’s heavily featured in the pepperpot I grew up with. Even with light use, cassareep imparts its preservative qualities to dishes like boily boily, a more delicate recipe made in the Guyanese interior with fish, beef, venison or other wild meat.

The ingenious uses of the bitter cassava root reveal how much rich cultural knowledge we hold in the Caribbean—knowledge that deserves to be preserved and celebrated. While our cuisine is undervalued both globally and by ourselves, we have meals like pepperpot, a technological marvel of a dish that upends the very basics of modern Western food preservation. When we embrace these foods and the legacy of our Caribbeanness, we begin to heal the wounds that colonialism has inflicted on our identities and nurture the aspects of ourselves that our ancestors were forced to discard.

To write this article, I had to eat some pepperpot. To my delight, our family friend Lynette Joseph-Brown, who hails from Linden, a mining town in northeastern Guyana, offered to come to my mother’s house and cook her version of the dish with us. In the middle of December, the timing was impeccable. “Pepperpot was Christmas,” says Aunty Lynette. Growing up, her meals would sometimes be very simple, but Christmas was when her family would enjoy more elaborate dishes—Chinese chow mein, Indian curry, Creole cook-up (a rice and peas dish similar to our Trini pelau) with extra meat and, of course, Indigenous pepperpot. In typical Caribbean fashion, these celebratory foods represented the diverse history of the region.

On a Sunday morning, my mother and I headed to the San Juan market near our family home to purchase ingredients for the dish. I braced myself for a flurry of activity, smells and noise. To my surprise, despite the festive decorations and booths filled with vegetables, fruit and Christmas accoutrements, the place was fairly empty. We went to the back of the market, where the butchers lay out their locally sourced meat and fish on a maze of countertops. We decided on a few cuts: a bag of pork, some cow heel and some beef and pork ribs. We got into an ole talk—a Trinidadian Creole term referring to typical chit-chat—with the beef butcher, who lamented that not many young people come to the market anymore, especially for local meat. “They prefer to go to the big groceries where they can get everything in one place,” he said. My mother and I continued our search for the elusive oxtail, and after a few more stops, we found a small, expensive batch in the frozen, imported section of one of the larger grocery stores.

Oxtail was once a simple and accessible poor man’s food that was essential to a Caribbean diet. It has since become the latest food fad, and is now a luxury due to its global popularity. When my mother and I groused to Aunty Lynette about how expensive oxtail has become (“They gentrified oxtail!” exclaimed my mother), she replied that we didn’t need to go through the trouble of getting it. For her, pepperpot can be more about utilizing what is available. Her recipe, highly adapted from how it would have been made in her homeland, features our local scotch bonnet peppers in place of the traditional wiri wiri, a round, cherry-like red pepper from Guyana. Instead of married man pork, an unusually named Guyanese basil, she uses the more common sweet basil.

This mindset of focusing on what we produce locally rather than relying on imported goods is part of a wider conversation about food security in the Caribbean. In 2023, the United Nations’ World Food Programme and the Caribbean Community (CARICOM)—an intergovernmental organization of countries in the region—found that 3.7 million people in the English-speaking Caribbean face food insecurity. This lack of access to affordable, nutritious meals is tied to the region’s high food import costs. According to CARICOM, some countries in the region import more than 80 percent of the food that citizens consume. The Caribbean’s dependence on food from abroad leaves us vulnerable to issues outside the region that might disrupt food production, like natural disasters or conflict. These events could cause sudden hikes in food prices and threaten the availability of staples, making it difficult for people to meet their nutritional needs.

But strengthening the region’s agricultural sector isn’t a simple feat. Heatwaves have affected many of Trinidad’s plants, including the married man pork that my mother recalls once growing in her garden. Climate change has also shifted the amount of water needed to irrigate fields and increased the spread of crop diseases. After the Caribbean’s dry season gives way to the downpours of the rainy season, devastating floods can deeply affect the farming community: in 2018, Trinidadian rice farmer Richard Singh told a national newspaper that he lost almost three million Trinidad and Tobago dollars (about $600,000 CAD) worth of equipment and nearly two hundred acres of crops due to flooding.

In Guyana’s interior, Casimero’s community of Aishalton is facing a climate-induced food shortage. Farmers in the administrative zone of Region 9, where her village is located, have been increasingly affected by adverse weather conditions over the past few years. In an interview with Guyanese newspaper Stabroek News last September, Charles Simon, a leader from Awarewaunau—another Region 9 community—said most of his village’s cassava crops had been wiped out by floods earlier in the year. Although the crops were replanted after flooding abated, El Niño, a warming weather system that arrived in the Caribbean later in the year, caused them to rot more quickly from excessive dryness. Due to this, production of cassava goods had to scale back, affecting both Awarewaunau and Aishalton, which depends on Awarewaunau farmers to supply many of their cassava-based staples. With climate change hurting crop yields across the Caribbean, imports have had to fill the gaps.

As members of CARICOM, Trinidad and Tobago and Guyana have taken a pledge to cut the region’s food import bill by 25 percent by 2025. The Guyanese government has stated that it is embarking on a series of projects in aquaculture, livestock farming and crop cultivation in hopes of expanding production of items like wheat, coconut, onion, ginger and turmeric. Despite these pledges, there is still not enough support for farmers. Perhaps this is due to the region’s experience with the plantation economy. For hundreds of years, our relationship to agriculture was closely tied to the exploitation of our people and the enrichment of European nations. It can be difficult to reconcile our need to grow what we eat with the historical trauma of plantations. The structures of our economies themselves were shaped by our colonizers, who prioritized extracting raw resources and selling them abroad. The improper development of the Caribbean’s agricultural sectors under colonial rule is a burden we still bear.

Reducing the Caribbean’s dependence on food imports could be part of the process of working through this historical trauma. But the concept of food sovereignty is more holistic than just encouraging us to grow more products at home; it asks that we focus not only on ensuring that the population can access food, but that this food is nutritious, culturally relevant and produced in environmentally sustainable ways. The approach also prioritizes people’s right to shape their own food systems.

Instead of imagining an agricultural future with rows of identical crops similar to the sugar and cotton production that traumatized our ancestors, we should look to Indigenous food forests as the way forward. They’re a long-practiced alternative to conventional agriculture, working with the ecosystems that are present rather than reshaping them. Indigenous food forests often feature edible and medicinal plants growing together in an interconnected and self-sustaining way. There are other similar methods that encourage plants to work together and feed one another and the soil, rather than degrade the earth. In Central and South America, Indigenous peoples practice the Three Sisters technique of planting, where squash, maize and beans are grown together. The stalks of corn act as trellises for the beans to climb onto, while the beans’ nitrogen-fixing properties fertilize the soil. The squash provide shade, keeping the ground moist and free of weeds.

Casimero hopes her community can reclaim traditional farming methods and knowledge of soil, weather patterns and ways of identifying arable farmland. She says the farmers who are following these traditions can better cope with the challenges of climate change: “Those are the people who have food on their table, and they are the ones supplying the populations in the village with traditional food.”

Looking to Indigenous communities for leadership in food sustainability is one aspect of re-Indigenization, a global movement to better incorporate Indigenous values and worldviews in a modern context. The first person to put the term on my radar was Gillian Goddard, an activist and the founder of the Alliance of Rural Communities of Trinidad and Tobago (ARC), a non-profit organization that aims to connect and support rural populations throughout the Caribbean. Goddard says it’s important to engage with sustainability in a holistic way. “It’s about creating community, which is fundamental to Indigenous values. If anything, that’s more important than the food itself,” she says. For her, decolonizing our relationship to what we grow and consume requires us to not just think about returning to the meals of the past, but to look at where our food comes from, who is profiting from food production and how we can shift these systems to better support communities. At ARC, she prioritizes empowering rural communities that hold this ancestral knowledge and act as guardians of the land, rather than allowing corporations to swoop in and claim profits for themselves.

When Goddard founded ARC in 2014, her focus was on transforming the local cocoa industry. One of the main varieties of cacao, trinitario, originated in Trinidad and Tobago hundreds of years ago. For centuries, raw trinitario would be harvested and sent off to be made into high-quality chocolates in Europe. But cacao production in the country plummeted in the mid-twentieth century due to a drop in world cocoa prices, the spread of pests and plant diseases and a national shift toward the oil industry. According to the University of the West Indies Cocoa Research Centre there are now about fifty thousand hectares of abandoned cacao fields across the country, sitting as remnants of our colonial past.

Goddard and her team see an alternative to the extractive nature of the cocoa industry. ARC works with rural communities that tend cacao trees to create community-owned companies and make artisanal chocolate locally. The organization provides residents with training and equipment, helping them develop new skills and feel a deeper connection to the products of their farming. Ultimately, rural communities are able to make more money through chocolate sales and tourism than they did from exporting cacao. ARC’s model presents a chance for people to rehabilitate their relationship to a crop that once represented their exploitation, while providing a guide toward a more sustainable and empowering relationship between communities and the foods they produce.

On a smaller scale, Casimero says it is important for people to not only support local farmers, but to begin growing their own food and not depend solely on products that come from others. Goddard has a backyard that is something of an urban homestead; to the untrained eye it may look like an unidentifiable cluster of trees and bushes, but there are fruit- and vegetable-bearing plants, rotating crops and a chicken coop. Community, for her, means living alongside the earth, being mindful of the people, plants and animals we cohabitate with and rejecting the hierarchies of capitalism. Everything feeds everything else.

On the day Aunty Lynette, my mother and I cook pepperpot, we venture out into my mother’s little garden to forage for herbs. With butterflies and hummingbirds flitting overhead, the garden is a little green respite from the bustle and concrete around us. As we collect fine leaf thyme and bird peppers, I think of how much love and care my mother has poured into this space, from toting bag after bag of dirt to cover a barren backyard, to populating it with an explosion of colours. Even as the temperamental climate decides what lives and what dies, the garden remains a place of hope, suggesting that something will grow again.

Back in our kitchen, as the hours pass, the rich, sweet smell of cassareep bubbling in the pot gives way to the scent of warm bread rising in the oven. With a splash of vinegar, the pepperpot is finished. Aunty Lynette takes a spoonful and empties it into my palm to taste. As the flavour hits my mouth, it unlocks a memory of being in my grandmother’s house many years ago. I am almost brought to tears, much to everyone’s consternation. It is an unexpectedly emotional moment for me, and it might be the first time I have cried for Granny Dot since her passing. I sit with my feelings for a spell, grateful for this opportunity to connect with a part of myself I didn’t realize needed connecting with. “Thank you for making this meal and for making me cry,” I say to Aunty Lynette afterward. “I’m not sure how to take that,” she laughs.

My mother, Aunty Lynette, her daughter, a few friends and I gather around the dining table with bowls of pepperpot and fresh bread in hand. Between the laughter, conversation, sharing of stories and divvying up of labour, there is a warm sense of community in the air. As Goddard says, it is this community that is the most vital part of designing a more livable Caribbean. While we consider how to tackle the effects of climate change on our region, it is our willingness to come together, learn from our history and see how our traditions can fit into a modern context that will allow us to solve collective crises as they arise.

When I spoke with Casimero, she told me about the Wapichan tradition where neighbours, family members and friends come together to accomplish a specific goal. “We still do the traditional way of self-help, which we call manore in our language,” she says. For her farmer parents, a typical manore would be an activity like weeding the farm. Casimero would contribute by cooking a big pot of food and bringing drinks for everyone who helped with the weeding process. “In that way, I support my parents and I also reap the benefits of whatever they farm,” she says. The community is able to come together, socialize, laugh, eat and get the work done as a collective. A lengthy process is made manageable through the participation of the whole village—similar to how bitter cassava is traditionally harvested and transformed from a poisonous root into a delicious, edible staple through the work of a community.

Food and community: the more I look into them, the more the two seem inextricably linked. It’s not just about being in community with those around you, but with those who came before you. “As an Indigenous person, I was taught by my grandmother to always treat food as something that is sacred,” says Casimero. Her grandmother and mother taught her to make Wapichan traditional foods, and she passes those traditions on to her four children. Aunty Lynette similarly learned how to make her family’s traditional fare from her mother, and she now teaches her kids the same, sometimes learning new techniques from them along the way.

I have found ways to learn from my own ancestors, even when their traumas prevented them from sharing the depths of their knowledge. It would have been a mistake to venture into recreating my grandmother’s dish on my own. In the end, it was the process of engaging with my community, hearing people’s stories and partaking in the experience with them that unlocked the essence of pepperpot. The dish reveals the ingenuity of our ancestors’ collective knowledge. It was not simply about using the world around them, but about sharing it and nourishing one another. ⁂

Amy Li Baksh is a Trinbagonian writer, artist and activist with a passion for Caribbean history, culture and all things creative.