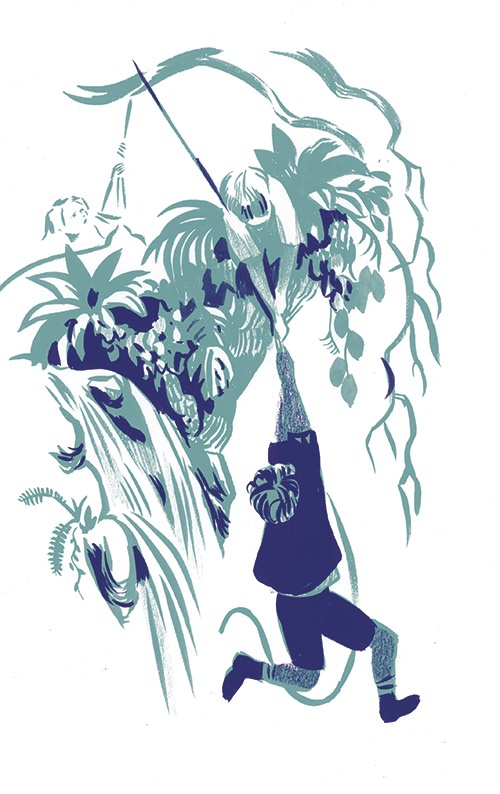

Illustration by Katty Maurey

Illustration by Katty Maurey

Vicarious Danger

Nineties survival series Real Kids, Real Adventures was an unlikely balm for intrusive thoughts.

The year is 1999. My sister and I are sitting with my nonna at the upstairs kitchen table, the espresso humming and whistling in excitement on the stove. It is morning but still dark outside, and my mom has just dropped us off on her way to work. When I think of my mornings that year, what comes to mind is my nonna’s dark green robe; a bowl of hard-boiled eggs in the middle of the kitchen table; my nonno’s morning grapefruit slices, which he doled out generously; and the TV show I would watch every day before we headed over to our elementary school down the street. With the light cascading through the window as I lay on the long couch, I gleefully change the channel—no more boring Italian news. Real Kids, Real Adventures is about to begin.

Real Kids was a Daytime Emmy-nominated anthology series that aired between 1998 and 2000. There were three seasons consisting of a total of thirty-nine half-hour episodes reenacting heroic stories of rescue and survival that young people actually experienced. A true cultural artifact of the late nineties, the opening title sequence, particularly the theme music, was shockingly similar to that of The X-Files. The opening credits showcased a montage including a seemingly endless supply of rescue helicopters and planes, extremely corny special effects, a close-up of a shark, poisonous chemical symbols, sirens galore, a hot-air balloon on the loose and a young boy shouting “mayday!” into a walkie-talkie.

Afterward, an eager teen host would stare into the camera, doing their best to channel both relatability and Serious Adult TV Presenter. The first three-quarters of the episode was a dramatization of the real adventure, while the latter part had the young host interviewing the actual kid whose story the episode was based on. The crux of the story could be anything: plane crashes, avalanches, bear attacks and forest fires; being lost in a swamp, on a glacier, in a desert. Admittedly, the acting ranged from painfully wholesome to considerably cringe. But to my not-so-discerning young eyes, this barely registered; I was too swept up by the high-stakes drama.

Real Kids, Real Adventures began as a series of books by Deborah Morris for young people between the ages of eight and fourteen. Early in her journalism career, Morris wrote real-life and drama features for Reader’s Digest, eventually accumulating a number of rescue and survival stories. “I started noticing that when it was adults involved, I could almost script in advance the kind of things they were going to say,” Morris tells me. The adults in she reported on were paralyzed by regret that often devolved into self-loathing for not thinking ahead or being prepared enough for the disasters that struck them. In contrast, she says, “if there were adults and kids involved, it was often the kids that saved [the] adults, and they didn’t have any guilt.”

Morris recalls an example from her early reporting days. A father and his two sons went cave exploring, only to find themselves lost. With no food or provisions, stranded in the dark cave, the boys immediately sprang into action. In contrast, their father was passive, descending into his own private depths of despair. “The kids weren’t sitting there ripping themselves apart, they just focused on what to do in the moment,” Morris tells me, as she launches into describing some of the creative (and quite literally batshit) ways the boys tried to find their way out. Hearing the bats flying out of the cave every night in search of food, they hatched a plan to catch one, tie some threads from a sock to its foot and follow it as it hopefully led them to an exit. Sadly, their plan did not get off the ground, so to speak, although eventually all three were rescued.

“They’re outshining us,” Morris states emphatically about kids often being the first to act in emergencies while adults waver, calculating risks or debating if they’re obliged to intervene at all. I’m reminded of the ski lift episode of Real Kids, where a small girl slips from her chair and is dangling by one arm from a ski lift. The teen ski resort employee is the first to act, climbing the lift tower, jumping onto the cable and pulling the girl to safety.

“Kids have an instinct to heroism,” Morris tells me. “I respect kids. I respect their abilities. I respect their capabilities. It is our failings as the adults in their lives for not equipping them—we should be.” Arguably, this is what she set out to accomplish with Real Kids: to equip children to be their own heroes. “I deliberately put in a lot of the detailed how-to stuff, for the purpose of intentionally trying to pass on knowledge that kids could use,” Morris says. She wanted to give young audiences the confidence to believe in themselves and their abilities, to know that inside each of them was the soul of a hero, just waiting for the right time to emerge. In a world in which young people face countless obstacles—mental health issues, climate anxiety, abuse and the struggle to assert their individuality—the lessons and stories of Real Kids, Real Adventures offer a compass of sorts, pointing readers and viewers in the right direction should they ever happen to lose their way.

I was obsessed with Real Kids, Real Adventures. I know this reads deliberately hyperbolic, but it is the closest, clinically speaking, to the truth. As a young person with a severe undiagnosed anxiety disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), it soothed me like no other show could. It seems odd: how could a show about life and death scenarios befalling other kids make me feel calmer and more secure? But Real Kids presented me with definitive proof that if those kids could make it through the very worst, so could I. Transfixed, I studied their stories, imprinting them into my brain, retracing the kids’ steps toward survival. Not everyone was happy about my love for the show; to this day, my younger sister Natalie accuses me of traumatizing her and giving her nightmares with my remote-hogging ways by forcing her to watch Real Kids with me every morning before school. Gripping the remote securely, I’d already begun memorizing the kids’ tales of survival as though my life depended on it. To me, my life, along with the lives of my family members, truly did depend on it.

OCD is a debilitating psychological disorder revolving around obsessions, recurring intrusive thoughts or images that can cause significant distress and anxiety; and/or compulsions, ritualistic, repetitive thoughts or actions, the performance of which can provide a temporary reprieve. According to the International OCD Foundation, pediatric OCD can occur at any age but generally begins to manifest between the ages of eight and twelve. Presentation of OCD symptoms in children and adults tends to be the same; but unlike adults, who can usually recognize the correlation between their obsessions and compulsions, children often do not have the language to articulate what is happening to them.

I can’t say for certain the exact age when my OCD started, but I do remember all the times I would lie awake in the dark as a child, refusing to go to sleep unless my feet touched together, perfectly even and symmetrical, while I recited a collection of nonsensical words over and over again in my head. If my feet moved out of alignment or if I didn’t repeat the phrase exactly right for a certain number of times, it would be my fault if something terrible happened. I saw graphic, horrific images of my mom in a car accident, her broken body slumped over the steering wheel, or my dad caught in machinery at work, crushed and paralyzed from the waist down. My life could fall apart at any moment, and it became my job to prevent that from happening. I was OCD Atlas, with the weight of the whole world on my shoulders.

Real Kids countered the awful stories my OCD conjured up, replacing them with stories that presented the possibility of transcending all the bad things that could ever happen to me and my family. The show helped me imagine worlds where the ability to survive was a given. Dr. Simon Lisaingo, a registered psychologist and assistant professor of teaching at the University of British Columbia’s School and Applied Child Psychology program, explains that kids may gravitate to stories of adventure and survival because they are often tales of hope and possibility. “It’s that hope of seeing what they could do, and the potential that they could do right,” he tells me. Maybe survival stories resonate so profoundly with us because they remind us that in times of danger we are more than capable of rising to the occasion, even when all hope seems lost. Perhaps this is why adventure and survival stories first come to us in childhood; they supply us with the golden twine we’ll later use to navigate the labyrinthine twists and turns of life.

Real Kids shares the same cultural DNA as the first modern English adventure story, published in 1719: Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, in which the titular shipwrecked protagonist is washed ashore on a desert island. Stranded in a strange and “savage” land, he initially struggles to survive, but comes to rely on his practical survival skills and reserves of fortitude to keep body, soul and imperial masculinity together. Deeply entwined with the history of empire and settler colonialism, the novel traces the various trials and tribulations of its “civilized” white male protagonist. For nearly three decades, Crusoe survives natural disasters, extreme temperatures, cannibals, pirates and perhaps the most terrifying of all, a profound loneliness and longing for home. Spoiler alert: Crusoe makes it off the island in one piece, and triumphantly returns to “civilization.” A gripping tale of survival, self-reliance and ambition, Robinson Crusoe is an adventure story that remains deeply embedded in our cultural imagination, and that launched a thousand imitations, referred to as robinsonades. Pauline Dewan, a children’s literature scholar, refers to it as “the parent of the children’s survival novel.”

If Robinson Crusoe is the archetypal parent of the children’s survival novel, then 1812’s The Swiss Family Robinson is its jovial, slightly pedantic relation. It follows the story of a shipwrecked family stranded on a desert island; using their knowledge of the natural world, coupled with their practicality, resourcefulness and Christian values, they flourish in their new tropical environment. Swiss pastor Johann David Wyss wrote the novel with his four sons in mind; like Real Kids, it employs robinsonade adventure story tropes in a how-to guide meant to better equip young people to handle disaster, or at least disastrous intrusive thoughts.

Frieda Wishinsky, author of the middle-grade Survival series, believes survival stories are for ordinary people, “not mountain climbers, not people who sail the world by themselves, [but] people who’ve been thrust into a dangerous situation that they didn’t expect to be dangerous.” Wishinsky’s young characters face natural disasters and dire situations with only their courage and wits to save them. She thinks this is exactly why these stories hold so much fascination: “You find courage or fear, both living side by side. Sometimes you do what you have to do, even though you’re terrified.” Survival and adventure stories give us a taste of danger, a chance to identify with the robinsonade protagonist at a comfortable distance while considering how we would act in such situations.

The realness of Real Kids’ stories impressed me the most, especially the interviews with the survivors at the end of every episode. Here, before my very eyes, was the triumphant return of the robinsonade hero after their time stranded on the desert island. Here, on the TV screen, our castaways were alive, intact, invincible. Stretched out on my nonna and nonno’s couch, I became a witness to their survival, attentive to every detail of their testimonies. Something about the authenticity of their recountings profoundly affected me. “To see the actual real kids just drove home to young viewers, ‘A kid like me did this. I can do that. It’s in my reach to help others in an emergency,’” Morris says, reflecting what I suspect my own internal monologue was at the time—I can be a hero too.

Part of it, I suppose, is that these stories of adventure and survival are tangible: the characters are trying to overcome the material obstacles that endanger their physical being, like a shark’s incisors or a mountainous terrain. In contrast, anxiety disorders and OCD are intangible, but present their own kind of treacherous terrain. Real Kids was for me as a child what therapy and medication would become for me as an adult: a way to neutralize my OCD, shrinking its gargantuan hold over me as I claimed more and more space for myself. These tangible stories gave me the hope and courage I needed to wrestle with, endure and overcome my intangible inner struggle.

Seeing others’ tales of survival can help young people believe in their own potential. “Maybe they don’t need to go out and climb Mount Everest, but to know that people have done it,” says Lisaingo. He explains that, according to self-determination theory, in order for children to feel like they can exercise control over their lives, they need three things: autonomy, to exercise agency without having adults constantly telling them what to do; competence, to feel like they’re accomplishing something and proving their worth; and a sense of belonging. I’ve come to think that children’s survival stories are places where kids can live out their own self-determination. These stories take kids seriously, teach them practical skills and give them the confidence to believe that they too are powerful—perhaps even more so than the adults in their lives.

There’s a Real Kids episode I have not quite stopped thinking about. “The Language of Life” is unique in the show’s oeuvre as it tackles the banal racist xenophobia so characteristic of Canada and the United States. Alexandra has just moved to the US from Peru, and is terrified of starting at a new school. She dreams of a blonde white girl, her face aghast at the sound of Alexandra’s heavily accented English. Then, shortly after Alexandra’s newborn cousin is born, disaster strikes: her cousin stops breathing, and Alexandra must muster up the courage to use her imperfect English to call 911 and be walked through how to revive the child.

In her interview after the reenactment, the host asks Alexandra whether she’s always calm and naturally in control, noting that it must be a big help to her family. She replies, “yeah, so they don’t get scared.” Her story resonates with me: like Alexandra, I too am an eldest daughter of immigrants who learned early on how to protect her relatives from things that would scare or upset them. Like Alexandra, I too am marked by this word: resilience. It’s a word that I have, for a long time now, bristled at. My whole life, I’ve been complimented for seeming to possess this quality; but I’ve felt that, instead of praising others for showing resilience, we should interrogate the circumstances of this world that necessitate resilience in the first place. I dream of dismantling this world of adversity and struggle in which our resilience is required and fetishized.

During my conversations for this piece, I was confronted with another meaning for this most thorny of words. According to Lisaingo, “resilience is our personal ability to overcome misfortune, difficulties or challenges. But in order for us to do that, we need social supports to help us.” Lisaingo does not frame resilience as a purely individual quality—it emanates from the collective: “Rather than focusing on what’s wrong with the kid, and blaming them for not being resilient, what are we doing to support that kid? What community structures are in place to support kids to be resilient?” To him, resilience comes from being built up by the adults in a child’s life, alongside community-based support systems, not from disconnected, rugged individualism. There comes a time when each of us must inhabit our own custom-made resilience, wearing it around us like a second skin. But, Lisaingo maintains, our individual resilience is not meant to be greedily stashed away for our own private use; quite the contrary. “At the end of the day, you share it with others,” he explains.

Dr. Danica Gleave, a retired family physician from Victoria, B.C., is no stranger to sharing resilience. She has been a volunteer with Scouts Canada for over twenty-five years, working primarily with Beaver Scouts (ages five to seven) and as a nature guide for grades four to eight. Every chance she gets, Gleave gives the kids the opportunity to do things for themselves to build their self-confidence. “It’s part of our culture that we believe in their capacity. We believe in them,” she says proudly. She tells me about her special bottle of ketchup labelled “blood” that she takes out on first-aid days; in pairs, one of the kids will be given a fake wound, and the other will be instructed to take care of them by putting on gloves, cleaning the wound and sticking on a Band-Aid while using comforting words.

On a hike, if a Beaver Scout stumbles and scrapes their knee, they ask to stop and take out their first-aid kit so they can put a Band-Aid on; the whole group sees the Scout being independent, and they learn that they’re able to take care of themselves if things get more challenging. Gleave trusts in kids and takes them seriously by inviting them to be active participants in helping themselves and others. They’re given the affirmation they need that they’re powerful agents, not powerless, passive beings in need of constant adult protection and coddling. This is the same affirmation given to young audiences of survival stories like Real Kids; a sense that resilience is possible and powerful beyond measure.

On an inky black morning before school, my nonna and nonno’s house is filled with the aroma of grapefruit and pane con l’olio. As if in a trance, I get up and walk to the living room, internally rejoicing when I hear the familiar theme music and see the title sequence of Real Kids, Real Adventures. This episode features the story of Ashleigh Wiggins, who’s rehearsing to play Juliet Capulet in her school production of Romeo and Juliet. As she saunters down the stairs, airily reciting her lines, her mom asks sarcastically if she plans on wearing her costume while hiking. Our young thespian pouts and explains all the reasons why she doesn’t want to go hiking with her mom and sister. The scene then cuts to Ashleigh all alone, lost on a snowy mountainside as her panic rises. To stay calm, she decides to rehearse her lines. “Goodnight, goodnight! Parting is such sweet sorrow,” she fearfully exclaims, pacing back and forth, occasionally glancing at her copy of Romeo and Juliet as if to confirm her command of the script. Eventually a helicopter spots her, and once reunited with her family, her mom apologizes for making her go hiking against her wishes. Without missing a beat, Ashleigh responds, “No, mom, it was better. I know my play backwards and forwards!”

Like Alexandra, Ashleigh is decisive, calm, resilient. She’s absorbed in memorizing her lines, distracting herself from the terror that we all know lingers just below the surface. By being determined to stay put and wait for help, Ashleigh exercises her agency and autonomy, competent and confident that she’s made the right choice. Just like the castaways of yore, stranded alone in a vast wilderness, our star-crossed heroine courageously clings to life. It seems fitting that she sought refuge in the pages of a book. In the darkest of times, she told herself a story in order to survive. Isn’t that what stories are for, after all? ⁂

Felicia Gabriele is a writer, historian and educator based in Montreal. Her work has appeared in the Rambling, Electric Literature and elsewhere. You can find her on X and Bluesky @FeliciaGabriele.