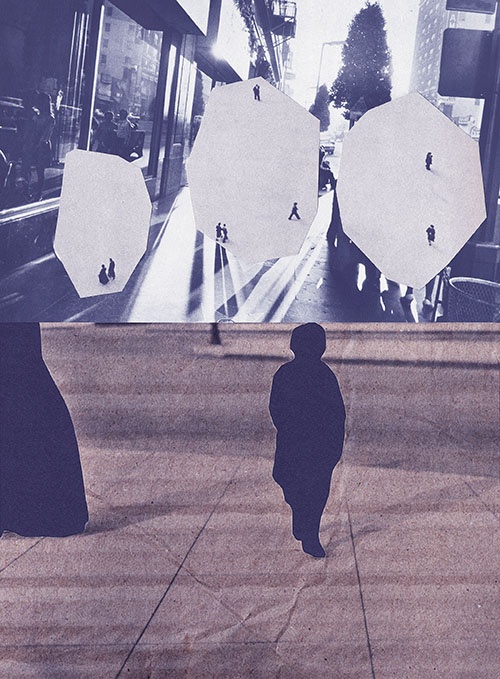

Illustration by Clea Christakos-Gee

Illustration by Clea Christakos-Gee

Nowhere to Rest

A new wave of bylaws sweeping Canada threatens to make public space more exclusionary.

“What is the intended purpose of a sidewalk?” It’s a question I pondered as I wandered city streets with my son this past winter. In Montreal, I hold his hand and dance wildly down the sidewalk in the rain, still buzzing from the frenetic energy of a DJ spinning in Place des Arts. In Toronto, we squat on a curb outside Union Station after dark, waiting for my dad to pick us up and drive us to the suburbs. In our home city of Kingston, Ontario, we linger for a lengthy snack break on a downtown bench outside a health food store, my tired son reluctant to make the walk home.

I started considering whether my use of sidewalks is appropriate after I heard the question uttered by Joe Hermer, associate professor of sociology at the University of Toronto Scarborough (UTSC). Hermer had been speaking against a proposed Community Standards bylaw in a presentation to Kingston’s city council last November. The bylaw would regulate “nuisance” behaviours in public space, prohibiting activities such as loitering, causing disturbances, urinating, defecating or displaying drug paraphernalia. While some of these behaviours are already prohibited by the Criminal Code, supporters of the bylaw argued that they are typically seen as minor offences and are often ignored by the police. The bylaw would give the city additional tools to discourage such activities.

The Community Standards bylaw was introduced in response to some residents’ and business owners’ concerns about public safety. In Kingston, the urban centre with the second-lowest vacancy rate in the province, homelessness has increased as community members face high rents and a lack of shelter beds. These shifts have made the unhoused population increasingly visible downtown, prompting unease. A member of a local hospitality association—a major supporter of the bylaw—argued that visitors perceive Kingston as an unsafe destination. She claimed that hotels were having problems staffing their properties because workers didn’t feel safe walking home. In an op-ed on the Community Standards bylaw for the local Kingstonist News, councillor Gregory Ridge recalls an incident where someone yelled misogynistic words at his wife. It was not an uncommon occurrence, Ridge writes, based on what he’d heard from other residents. He notes that while he understands that unhoused people face systemic barriers, everyone in the community deserves to feel safe.

Ridge’s concerns parallel growing anxieties about homelessness across Canada. In a study of eleven communities, the Canadian Alliance to End Homelessness found a 40 percent increase in chronic homelessness from 2020 to 2023. Since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, more people have been living in encampments across cities big and small. Debates about how the government and the public should respond to these visibly unhoused populations have raged in many communities. In places like Toronto and Vancouver, municipal officials have cracked down on encampments, citing the importance of maintaining public health and the availability of public space. Other cities have implemented anti-homeless policies like Kingston’s proposed bylaw, limiting activities such as panhandling or scavenging for recyclables.

In his op-ed, Ridge suggests that Kingston’s Community Standards bylaw had been carefully crafted to target behaviours, rather than specific groups of people. The bylaw defines the act of loitering as “to use or occupy a space other than for its intended purpose or to occupy a space such that it is not usable by others.” But, as Hermer’s question to city council points out, the “intended purpose” of public spaces such as sidewalks is rarely clear. This vagueness opens the door to discriminatory enforcement against unhoused and street-involved people, who are more likely to be targeted by bylaw officers because of complaints by wealthier residents and business owners. Ultimately, these laws disproportionately affect those who can’t easily access private places to sleep, use the bathroom or use drugs.

Hermer was just one of the many advocates who pushed back against the bylaw at the meeting. A lawyer discussed how the bylaw would advance discrimination against unhoused people and those facing mental health and addiction challenges, potentially violating human rights codes. A doctor spoke to the unfairness of fining people for urinating or defecating in public given the lack of twenty-four-hour public washrooms. A nonprofit leader argued that the bylaw would likely harm racialized and other vulnerable people. A nun urged councillors to support unhoused people, rather than punish them.

For my son and I, the presence of such a bylaw is moot, protected as we are by our white skin and middle-class markers. We also have the ability to move ourselves and our belongings to a home—be it a friend’s, a family member’s or our own—if needed. In all likelihood, our ability to dance, wait, rest and snack on a city street is not in jeopardy. But for those whose home is a tent, a doorway or a shelter bed only available for twelve hours a day, such regulations on activities in public space present difficulties. Without a stable place to rest or live, they are forced to endure an exhausting cycle of moving from place to place.

Kingston’s bylaw was ultimately passed by city council with a few amendments, and came into effect in May. It’s just one example of what the COVID-19 Policing and Homelessness Initiative, a UTSC-based research project led by Hermer, refers to as “neo-vagrancy laws.” Over the past three decades, these laws have emerged in municipalities across Canada under the pretense of public safety. They ostensibly simply limit activities such as loitering, camping in public places and causing nuisances. In reality, they’re the latest iterations of vagrancy offences that were designed to “punish people who are visibly poor and have no choice but to spend their time in public spaces,” according to the initiative’s website. These bylaws are one piece of a larger regulatory system meant to drive unhoused people out of view. Rather than protecting our collective wellbeing, neo-vagrancy laws prioritize the comfort of housed people and criminalize the public existence of the visibly marginalized.

There is a long history of regulating public space and those who exist within it. Federal vagrancy offences emerged in Canadian law under the 1892 Criminal Code. While the relevant section listed several acts associated with vagrancy, the offence was based on identity: a vagrant, or “a loose, idle or disorderly person,” could be fined or imprisoned. Vagrants were seen as threats to the moral and social order, and to the wellbeing of the nation. After the Second World War, the definition of a vagrant was removed, and the section was rewritten to define vagrancy based on specific acts: begging; prostitution; supporting oneself through gambling and crime while unemployed; loitering near schools, playgrounds, parks or bathing areas after being convicted of a sexual offence; and “wandering abroad or trespassing” without justification and while “not having any apparent means of support.” This change eliminated language that explicitly criminalized vagrants, placing the focus on behaviours. But the new language also widened the scope of the law substantially: any public or private space could be considered off-limits to those who appeared impoverished and unemployed.

The federal government began to limit the scope of the vagrancy section in the 1970s, as it reconsidered the role of criminal law and attempted to address its uneven application on marginalized groups. The 1970 Report of the Royal Commission on the Status of Women in Canada found that young, marginalized women were often convicted of “crimes without victims”—including prostitution—under the vagrancy section of the code. Under former prime minister Pierre Trudeau’s administration, there were growing debates about the appropriateness of policing behaviours in a free society. The Criminal Code was amended to focus on crime rather than morality, and the offences of wandering or trespassing without justification, begging and prostitution were decriminalized. In 1994, the Supreme Court of Canada struck down the offence of loitering in specific areas after being convicted of sexual offences, deciding that it was overly broad and infringed on rights guaranteed by the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. And in 2019, the vagrancy law as a whole was repealed from the Criminal Code.

While vagrancy offences are no longer federally recognized, they have found new life in municipal bylaws. Compared to their predecessors, these bylaws may not explicitly refer to vagrancy, but they continue to target the existence of unhoused and marginalized people. The COVID-19 Policing and Homelessness Initiative identified 367 neo-vagrancy offences in 217 municipal bylaws across Canada. The initiative outlines seven types of offences: panhandling, obstructing, scavenging, resting and sleeping, sheltering, causing disorder and loitering. The eighty-two anti-loitering bylaws are particularly notable because they target people for simply existing in public space.

The imprecision of the term “loitering” means that it can be applied in a discriminatory fashion. “It’s obviously massively subjective and can easily be weaponized,” says Nicholas Blomley, a professor of geography at Simon Fraser University whose research focuses on how legal practices relate to space. The vague language of anti-loitering bylaws allows authorities to selectively apply them to single out and police unhoused people and the marginalized communities that are often overrepresented in these populations: drug users, racialized people, LGBTQ2S+ people and disabled people.

Because the enforcement of municipal bylaws is typically driven by complaints, neo-vagrancy bylaws also deepen the power imbalance between housed and unhoused people. It is far more likely that a business owner will call bylaw enforcement on a homeless person smoking a cigarette than the other way around. “If I sit with my middle-class friends and we drink a glass of wine … I’m probably not going to get hassled,” says Blomley. “But if a visibly homeless person shows up, there’s going to be a different response.”

In 2022, Hermer conducted a report on the first ninety-nine days of enforcement of the Safe Streets Bylaw in Prince George, BC. The bylaw prohibits the obstruction of streets and roadways, as well as solicitation after sunset or in specific areas, like around bus stops, banks and daycares. It was passed after city councillors received complaints from housed people around the Moccasin Flats encampment, a downtown area where many unhoused and Indigenous people live. Some residents argued that they felt afraid to walk in the neighbourhood at night.

Hermer’s analysis revealed some of the biases that shape Prince George’s everyday citizens’ and bylaw officers’ understanding of who belongs—and who doesn’t—in public space. Eighteen percent of complaints filed by the public under the bylaw dealt with the mere presence of a person. Further, in 36 percent of complaints, bylaw officers described the offenders as “squatters,” a term typically used in relation to the occupation of private property. This language evokes the historical criminalization of vagrancy as a particular identity, suggesting that marginalized people can be dispossessed and excluded from public space.

City officials had claimed that the implementation of the Safe Streets Bylaw would focus on education rather than punishment or the collection of fines. During the course of Hermer’s study, no one was formally charged. In a 2021 comment to local news site My Prince George Now, former mayor Lyn Hall drew on this fact to combat controversy around the bylaw, arguing that it was in fact creating a positive impact. However, Hermer found that the informal approach to enforcement meant that bylaw officers were able to act with impunity in enforcing a “discriminatory view of public space that excludes the very presence of dehoused and unsheltered people.” Because no tickets were issued, there was no oversight or accountability for how officers implemented the bylaw: people who had been targeted had no legal means to challenge the methods of the officers’ intervention.

Hermer also didn’t recognize any educational components in bylaw officers’ responses to complaints. Instead, he noted that “bylaw enforcement systematically [focused] on ‘moving on’ unhoused people from public view.” While being asked to move might not seem like a big deal, for those who do not have a space of their own—who frequently have to carry themselves and all their belongings from shelter, to street corner, to another street corner and back again—this cycling through space quickly becomes exhausting and stressful. For some, being asked to move out of public view might increase their risk of overdose or other health emergencies, as they are less likely to be seen or helped.

Neo-vagrancy bylaws can also exacerbate the challenges that unhoused people face in retaining and protecting their belongings. Those who live on the streets lack safe, secure places to store objects of personal importance or items that are crucial to personal safety, like naloxone kits, medicine or ID. These belongings may be seized as part of bylaw enforcement, or lost as unhoused people are ordered to move. The loss of these items can affect unhoused people’s survival and mental health. It may even encourage the very behaviours that neo-vagrancy bylaws seek to eliminate, like causing public disturbances—an offence that authorities can use to criminalize people experiencing mental health crises in public.

Although we might imagine that public space is for everyone, the passing of neo-vagrancy bylaws makes it clear that public spaces are imagined for respectable citizens. That often means people who work and generally meet (or strive to meet) the expectation of property ownership. For these respectable citizens, regulating public space is often about protecting property from those who have less, and defending against issues like theft and vandalism. But Hermer’s research suggests that vandalism accounted for only about 2 percent of complaints during the first three months under Prince George’s bylaw. A 2019 study conducted in San Francisco likewise suggested that anti-loitering and other public nuisance bylaws do not deter behaviours linked to public disorder. Asking unhoused people to move on does not remove them from public space—it only encourages them to circulate through different neighbourhoods. Not to mention that vandalism and theft are already criminal offences, with heftier and more significant penalties than allowable within the scope of municipal bylaws.

All this implies that the privileged classes—business owners, tourists, “respectable” citizens—are getting something else out of these bylaws. Sophie Lachapelle, a Kingston-based researcher and PhD student at the University of Ottawa, suggests that the enforcement of neo-vagrancy bylaws represents “emotional transactions.” In her view, bylaws that criminalize poverty are partially about managing the uncomfortable feelings that arise among housed people when they encounter the unhoused: fear, anxiety, anger, disgust and pity. Rather than reckoning with the reasons behind these feelings, people support these bylaws to try to remove the problem from sight. It doesn’t matter whether the bylaws do anything beyond forcing unhoused individuals to regularly relocate. “If you see bylaw officers approaching someone, whether or not that interaction is going to be productive, just seeing that happen makes you feel safer,” says Lachapelle. Neo-vagrancy bylaws serve to sweep broader issues under the rug. They do emotional work for the housed, rather than implementing concrete solutions that would benefit everyone.

Lachapelle is still researching why we have such strong reactions to seeing unhoused people, but she has a few suspicions. While property is central—Lachapelle notes that some people may see any threat to property as “an existential threat” because of how deeply we identify with our belongings under capitalism—our emotional reactions aren’t always about protecting property values or the objects we own. Instead, unhoused people may threaten the classic capitalist narrative: the notion that respectable citizens must work and strive to own a home. Seeing people openly defy this narrative can cause anger or even confusion, as it challenges the idea that we all have equal access to private property.

In this sense, while vagrancy is no longer a criminal offence, its legacy very much lives on in our perspective of the unhoused as threatening the social and moral standards we’ve come to accept. “Instead of looking at the system that we live in as the problem, it’s a lot easier to look at other people and blame them for why the system isn’t working,” says Lachapelle. As the costs of rent and groceries far outpace wages, many Canadians are struggling to make ends meet. It can be easy for working people to look at those who are unhoused and unemployed and feel some disdain. But we’re united by the same underlying issues; we could all benefit from policies that make housing and food more affordable, mental healthcare more robust and decent work more attainable.

In contrast to a private space, which belongs to a specific owner who can generally decide whether to grant someone access, the definition of a public space is more slippery. While we may tend to think of public spaces as being open to everyone, Marie-Eve Sylvestre, the dean at the civil law section of the University of Ottawa’s faculty of law, says that they are in fact owned by the government. “Public spaces—such as a park, a street or a public place in a city—are the property of the city, the municipality, the province or, in some cases, the Crown,” says Sylvestre. “They have a relationship of ownership or control over the space, and they will be heavily regulated so that access is not completely guaranteed to anyone.”

What distinguishes public space from privately owned space is that it is supposed to be maintained for the wellbeing of the population. According to Sylvestre, public spaces are also commonly perceived as places that people can temporarily use and move through. Because they are meant to be accessible to all, long-term occupation would be akin to challenging the government’s property rights or interrupting everyone’s enjoyment of the space. But this narrative gives governments a great deal of latitude in determining whose enjoyment should be prioritized and what behaviours are considered disruptive. It also inherently criminalizes unhoused people who don’t have access to private space.

When it comes to challenging a municipality’s regulation of public space, the Constitution can be a useful legal tool. The scope of what a municipality can constitutionally do with public space comes down to two factors. The first is jurisdiction, which delineates the responsibilities of the federal, provincial and territorial governments. The provincial government dictates municipalities’ rights to regulate public space; if a bylaw were deemed to be infringing on criminal law, which is a federal matter, it could be ruled unconstitutional as it falls outside the jurisdiction of what the province can grant a municipality. But according to a 2015 article published by the Alberta Civil Liberties Research Centre, “it is not uncommon for certain by-laws to overlap in some areas with existing provisions of the Criminal Code.” For example, municipal bylaws may target less serious traffic infractions that are not criminal. The provincial government can allow such bylaws as long as their purpose and effect fall under provincial jurisdiction.

The Charter of Rights and Freedoms is the second factor that limits the ability to restrict the use of public space. Among other rights, the Charter guarantees the right to expression, “the right to life, liberty and security of the person” and equal protection under the law. These three sections can be invoked in challenges to neo-vagrancy laws. However, the Charter has only been used this way a handful of times. In 1999, the Ontario government passed the Safe Streets Act to prohibit “aggressive” panhandling, which famously included squeegeeing the windshields of cars stopped at red lights. Soon, a group of people who had been charged under the act mounted a court challenge. Some of them were represented by the Toronto-based legal organization Justice for Children and Youth (JFCY) and the Ontario Coalition Against Poverty (OCAP). The groups argued that the act denied vulnerable people’s rights to expression, liberty and equality. Specifically, JFCY and the OCAP claimed that the act prohibited many forms of asking for money, infringed on people’s right to earn money to survive and differentiated between legitimate solicitation for charities and solicitation by the poor—something which, if found valid by the courts, would have proved the act’s discriminatory impact on Charter rights.

In 2007, the Ontario Court of Appeal upheld the act, suggesting that impoverished people were free to ask for money in other ways and that the act did not formally discriminate between charities and others asking for money. The court agreed that the act infringed on the right to expression, because squeegeeing is a form of expression; however, it decided that these infringements were within the “reasonable limits” section of the Charter, which allows the government to limit individual rights if these limitations “can be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society.”

The court’s landmark decision on the Safe Streets Act was not promising for those looking to legally challenge neo-vagrancy legislation. It was perhaps particularly discouraging that the court ruled that because the act used neutral language and did not explicitly distinguish between charities and poor people asking for money, it did not violate Charter rights. Municipalities similarly rely on neutral language when insisting that neo-vagrancy bylaws do not violate human rights, regardless of how such legislation continues to specifically harm unhoused people.

However, this April, an Ontario judge struck down several provisions of the province’s Safe Streets Act after the Toronto-based pro bono legal clinic Fair Change Community Services launched a court challenge. Fair Change had argued that the act violated several Charter rights, including freedom of expression and equality rights for Indigenous people, LGBTQ2S+ people, youth, people who receive social assistance, people with mental illness and those with substance use disorders. The judge ruled that equality rights were not infringed on, but he did find that asking for money is an important form of expression, and that the act’s definition of “aggressive solicitation” was overly broad. The judge struck down several provisions restricting behaviours that he deemed not necessarily aggressive or threatening to public safety, including soliciting while intoxicated and at transit stops or ATMs. Though the court still failed to recognize the discriminatory impact of neo-vagrancy laws, the ruling suggests that in the future, governments may face challenges to their invocation of public safety as justification for broadly applied or ill-defined laws.

Recent rulings against bans on encampments also offer hope. Last June, the City of Kingston announced it would apply for an injunction to clear the encampment at Belle Park, a wetland-turned-landfill-turned-park that had become a popular place for unhoused people to shelter during the pandemic. The city had cited a bylaw that prohibits unauthorized camping in municipal parks. In November, Superior Court Justice Ian Carter denied the city’s application, deeming that the bylaw violates the Charter right to life, liberty and security. Carter found that unhoused people should be permitted to put up tents in parks overnight. But the ruling wasn’t a complete win; Carter also found that there was not enough evidence to show that a ban on daytime camping would breach Charter rights. In his decision, he ordered that an exception be added to the bylaw to allow unhoused people to set up shelter in parks from an hour before sunset to an hour after sunrise. The city has since begun to enforce a daytime camping ban, a move that some legal activists say is an unfair interpretation of the court’s ruling.

Sylvestre says that over the past two decades, research has been done to prove the discriminatory impact of anti-poverty bylaws. She’s trying to expand the amount of available evidence through her own empirical research, which focuses on policing and judicial practices that have discriminatory impacts on marginalized populations. She says bylaws restricting panhandling—which can affect people’s freedom of expression—remain particularly vulnerable to Charter challenges. As the discriminatory impact of neo-vagrancy bylaws is documented in more research, it will be harder for municipalities to hide behind seemingly neutral language that in practice targets unhoused people.

In a 2016 report published by the Quebec-based research group L’Observatoire des profilages, Sylvestre and Université de Montréal researcher Céline Bellot documented ticketing under a bylaw “concerning nuisances, peace, good order and public places” in the regional county municipality of La Vallée-de-l’Or in Quebec. The researchers found that between 2012 and 2015, tickets under the bylaw were most often issued for public intoxication, “uttering insults or threats” and public alcohol or drug use: all non-violent acts whose policing focuses on the supposedly improper use of public space. Seventy-six percent of the 3,087 tickets that were issued were given to Indigenous people. And of the sixty-seven people whom Sylvestre and Bellot described as over-criminalized—having received more than ten tickets each—94 percent were Indigenous. This is despite Indigenous people accounting for only about 8 percent of La Vallée-de-l’Or’s population in private households around that time, according to the 2016 census.

In many cities where neo-vagrancy bylaws have been introduced, Indigenous people account for a significant proportion of the unhoused population. In Kingston, Indigenous people represent about 3 percent of the general population, but 31 percent of those who are unhoused. In Prince George, which implemented its Safe Streets Bylaw, these figures are 15 percent and 68 percent respectively. These trends reflect the impacts of colonization and policies that have uprooted Indigenous people, including the residential school system and the child welfare system. “Settler governments continue to dismiss the ways intergenerational trauma impacts our communities and plays a role in homelessness,” says Terry Teegee, Regional Chief of the BC Assembly of First Nations, in a 2022 press release. “It’s all connected. Punitive, short-sighted policies like the Safe Streets Bylaw simply exacerbate the situation and prolong the crises.”

The specific marginalization of unhoused Indigenous people reveals not only the discriminatory effects of neo-vagrancy bylaws, but also the connections between the theft of Indigenous land and the regulation of public space. Municipalities are able to control public space because of their colonial relationship with Indigenous peoples, says Blomley. “It’s a relationship that assumes that the ultimate owner of the land is the Crown,” he says. “It denies the reality of Indigenous sovereignty and Indigenous title.” Indigenous people are more likely to be unhoused precisely because they were dispossessed of their land—the fact that they now may face fines or be asked to move on simply because of their presence in public space creates a kind of double dispossession.

Indigenous activists have been quick to seize upon this point. In 2014, the City of Vancouver notified unhoused people camping in Oppenheimer Park of an impending eviction. The park is located in the Downtown Eastside, a neighbourhood home to many unhoused people. Two residents of the camp, Brody Williams of the Haida Nation and Audrey Siegl of the Musqueam Nation, handed the city its own eviction notice, stating that the park was located on unceded Indigenous land. The city responded in an official statement to the CBC, recognizing that a disproportionate number of unhoused people in Vancouver are Indigenous, but stating that the park needed to be kept open to “everyone.” In the years since, park rangers and police have cleared several encampments in the park.

Bylaw officers’ claims that public space is being used inappropriately are eerily similar to the rationale behind the seizure of Indigenous land centuries ago, which was in part based on the notion that it wasn’t being used productively. “We—white liberal society—value property, but yet we take Indigenous land and personal property away on the assumption that it’s not being used,” says Blomley. He points to the way neo-vagrancy bylaws are often framed not as punitive measures, but as educational interventions designed to funnel unhoused people off the street and toward resources such as shelters, regardless of whether people are interested in those kinds of living arrangements or whether adequate resources even exist. Many unhoused people reject shelters because they often lack privacy and impose restrictive policies, such as bans on substance use and pets, or gender segregation that prevents couples from sleeping together. Encampments can widen people’s social networks and help them access mutual support in a way that shelters often cannot.

As municipalities make commitments to reconciliation, their implementation of neo-vagrancy bylaws paints a very different picture of their priorities. When Indigenous people are overrepresented in unhoused populations, these bylaws are inherently racist; they perpetuate colonial relationships through further policing and displacement. To facilitate meaningful relationships with Indigenous communities, municipalities will have to engage Indigenous people and work toward more just solutions to homelessness.

In the summer of 2020, an anti-loitering bylaw was proposed in Kenora, a city in western Ontario. The bylaw would allow the city to issue a $100 fine if someone was found loitering, which a draft of the bylaw defined as “to linger, hang out, travel idly, and includes to rest and to stand, sit or recline without a purpose relating to or any activity which is contrary to the property.” Advocates argued that the bylaw would be selectively applied to Indigenous people, who represent 88 percent of Kenora’s unhoused population. “If you’re sitting outside reading a book, or you’re having a snack, or you’re a tourist from Manitoba, it’s all well and good,” says Marlene Elder, a community activist who is a member of the Lax Kw’alaams Band in BC and a longtime resident of Treaty 3 territory, on which Kenora is located. She notes that Indigenous people, poor people and those who use drugs and alcohol in public aren’t afforded the same treatment.

Elder helped organize “lunch and loiter” protests in front of city hall to highlight the bylaw’s discriminatory impact. On one occasion, protestors carrying placards marched to the patio of a local restaurant, where the mayor and some councillors were having lunch. Community members stood and held signs that read “For whose ‘public safety’?,” “Compassion is free, being homeless is $100” and “Strong communities loiter together.” Meanwhile, the councillors continued to chat nonchalantly and ignore the protestors.

Kenora’s bylaw was condemned by Grand Council Treaty #3, the traditional government of the Anishinaabe Nation in Treaty 3 territory, and Nishnawbe Aski Nation, an organization representing forty-nine First Nations communities in northern Ontario. In a news release, the nations called for a more collaborative and humane approach to tackling Kenora’s social problems, noting that “it is critical that these issues are addressed collectively by all those that share the land of the Anishinaabe Nation.” The Ontario Human Rights Commission also issued a letter to the mayor and city council, urging them to reject the anti-loitering bylaw on the grounds that it would likely disproportionately harm marginalized people.

On the day that city council was set to vote on the proposed bylaw, protestors gathered outside of city hall, waving signs and watching the meeting on their phones through Zoom. They cheered as the bylaw was rejected in a 6-1 vote, with some councillors stating that public opinion was critical in changing their minds, according to the CBC. For Elder, this victory was the result of grassroots activism and people coming together. She says the initiative has reinvigorated Indigenous resistance in the area. “It’s been about reminding people about the history, of what people have given up and how they are suddenly second-class citizens in a territory that was theirs,” says Elder.

Short of further success in the courts, these political gains are crucial in the fight against neo-vagrancy bylaws. In Kingston, activists will be keeping a close eye on an impact assessment promised by the city a year after the bylaw comes into effect. The third-party tool is supposed to examine any “unintended consequences” of the bylaw and add an additional layer of oversight. Lachapelle hopes residents will also reflect on the purpose of the bylaw and who it benefits. “If we can’t ask ourselves the really uncomfortable questions of ‘Who does this serve?,’ then we’re just going to keep repeating different manifestations of this bylaw,” she says.

As neo-vagrancy bylaws reveal, public spaces uphold exclusion. They are increasingly functioning like private property that only certain people are welcome to inhabit. But we can imagine a different purpose for public space; one where people of all kinds are able to dance, wait, rest, snack and live outside the confines of property and the discrimination that it represents.

Like the rest of us, unhoused people also need places to use substances, experience emotional meltdowns and have sex. Creating such spaces would mean reckoning with our deeply held beliefs around who deserves the space to live, and whether those who don’t work or own property deserve this kind of dignity. It would mean finding solutions to poverty that are rooted in harm reduction, where people are trusted to make the best decisions for themselves. And it would mean establishing housing options that are longer-term and subject to fewer restrictions than shelters—giving those who don’t own private property some access to space.

We can imagine a society where those who are unhoused, use drugs or live with mental illness are supported, rather than punished or pushed further into the margins. The question is, do we have the capacity to create it? ⁂

Jane Kirby is a writer, editor and circus artist living in Kingston/Katarokwi.