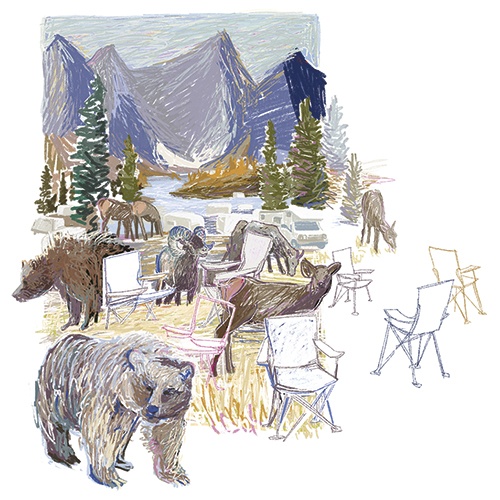

Illustration by Veronyka Jelinek

Illustration by Veronyka Jelinek

Grizzly Truth

The fate of a rare white grizzly bear reveals the uneasy relationship between conservation and tourism in the Rockies.

If you were to pack up your car in Montreal, load a camera, hiking boots, trekking poles, a canister or two of bear spray, and then proceed to drive west for thousands of miles on the Trans-Canada Highway, you would bear witness to a rapidly changing landscape. Leafy green forests and vast lakes gradually turning into a sprawl of golden grassland, dotted with pronghorns or pocked and scarred by decades of agriculture. After hours of flat, endless prairie highway, you might begin to grow anxious, eager to arrive at your intended destination. It is the mysterious promised land, heaven on Earth, beautiful and dangerous; the coveted reward waiting for you almost four thousand kilometres west of a dull urban existence. The Rocky Mountains. You’ve been enticed by posts that flood your Instagram feed with glacier-capped peaks, azure alpine lakes, meadows of wildflowers, abundant wildlife, long summer days and bright starry nights.

Like so many others, after years of living a confined and hectic life in the metropolis of Montreal, I heard a whisper beckoning me west, and I heeded it. I joined the ranks of other young people working seasonal gigs in luxury hotels for wealthy tourists. Like my peers, I landed in the Rockies to escape the monotony of my life; to spend my free time hiking up mountains, sleeping in the backcountry, for everything to feel uncharted and wild. It was a break from my reality.

The Rockies were created millions of years ago through the colliding of tectonic plates, which continue to slowly shift in a process imperceptible to the human eye. In comparison, the human population of the Rockies is startlingly transient. The townsites within the parks are overwhelmingly composed of touristic infrastructure—restaurants advertising elk on their menus, shops with flimsy-looking merchandise and souvenirs.

Millions of visitors flock to Canada’s Rocky Mountain national park ensemble—which includes Banff, Yoho, Jasper, and Kootenay—every year. Between crowded parking lots and park trails, visitors to the parks might see a whole host of animals, including moose, marmots, and, perhaps most infamously, grizzly bears. Dangerous and mostly solitary, grizzly bears are presented as the ideal of untouched wilderness in the Canadian Rockies. Taxidermied grizzlies tower over guests in museums, signs plastered in storefronts advertise “BEAR SPRAY SOLD HERE.” Bears and the wilderness wherein they roam are exciting, a promise which entices Canadian settlers to come and discover it, regardless of what that might mean for the wilderness itself.

The Rockies are part of the fearsome grizzly bear’s continually shrinking habitat. Historically, grizzly bears inhabited most of western North America, with their range stretching from central Mexico to the Arctic Circle and covering western Canada and the western United States. When European settlers landed in North America, however, they felt grizzlies posed a danger to their safety and to that of farm animals; in the nineteenth century, European settlers engaged in a larger project of grizzly bear eradication. By the 1930s, roughly 125 years after their first encounter with European settlers, grizzly bears roamed only about two percent of their historical range in the forty-eight adjoining United States, having experienced a corresponding population decline.

As grizzlies are highly sensitive to human activity, the western population was designated a “special concern” by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada in 2012. The British Columbia government has designated grizzlies as blue-listed (meaning they are of special concern) and in Alberta, grizzly bears are classified as threatened. Though increasingly confined, they play a vital role in the mountain ecosystem as apex predators. Grizzlies are an “umbrella species” in the Rockies—their conservation also protects multiple nearby species that share the same habitats and ecosystem. Because grizzlies travel far, often in search of places to feed and breed, from valley bottoms to forests to high alpine meadows, they overlap with many other species like marmots, ground squirrels, elk, and moose in their landscape. Grizzlies also dig prey out of their burrows and roots and tubers out of meadows, which aerates the soil and can support the growth of plants in alpine and subalpine meadows across the Rockies.

It is not uncommon for residents to see a grizzly bear—if you know where to look. As spring thaws the snow, grizzly bears emerge from hibernation and begin searching for sustenance. They awake groggy and famished after months of sleeping, and can often be seen munching on vegetation throughout the spring and early summer. That period in the Rockies is a popular time for human-bear interaction along the valley bottoms and highways in the parks, before they ascend into the alpine during the warmer summer months. Residents of the region’s Bow Valley, which includes towns like Banff and Canmore, have developed several tactics and management strategies for cohabitating with bears. Gareth Thomson, executive director of the Biosphere Institute of the Bow Valley, describes the Institute’s WildSmart program, designed to accelerate the coexistence of humans and wildlife in Canmore. The group has been engaged in a project going door-to-door to encourage residents to reduce and remove wildlife attractants—like the hundreds of crabapple trees planted throughout town that bears love. Thomson says that Canmore is working harder than most other municipalities in bear habitat to reduce bear mortality. “We’re wrestling with higher, more challenging questions. And I’m proud of the work we do,” he notes.

During my time in the Rockies, I had several accidental encounters with grizzlies in the parks, each one terrifying, awesome, startling, and weird. I would lock eyes with a creature before me, the furry beast munching berries or dandelions, who could tower eight feet tall over me and maul me to death with sharp claws and teeth—yet who also had sweet, soft-looking ears, a round, plush belly and startlingly emotive eyes. With my hand shaking on my bear spray canister and my eyes wide and unwavering, each encounter ended the same: the bear deeming me safe, a non-threat, and serenely walking away. I would return to the safety of my car relieved and shaken and full of adrenaline, feeling that I just passed some sort of judgement, received an act of grace, from a power much higher and more mystical than I could ever understand.

In the Rocky Mountain Parks, grizzly bears are beloved, adorned with celebrity and lore. According to Parks Canada, there are an estimated sixty-five grizzly bears in Banff National Park and eleven to fifteen in Yoho National Park. There is grizzly bear No. 122, known as The Boss, the Bow Valley region’s dominant male bear. With many estimates placing him at around six hundred pounds, he is a father to many other bears in the area. In 2010, he was reportedly hit by a train, and, miraculously, survived. There is Bear No. 136, called Split Lip, who is one of The Boss’ biggest rivals in the region, rough and rugged in appearance and personality, as his nickname suggests. Bear No. 142, one of the oldest and most successful breeding females in the Bow Valley, is often spotted by humans, as she tends to stay close to areas frequented by them, likely an attempt to protect her cubs from predators.

But in the past few years, one particularly unique grizzly has captured hearts in the Canadian Rockies: Bear No. 178, known as Nakoda. There are white polar bears inhabiting Canada’s Arctic region, and white or cream coated spirit bears, colloquially referred to as Kermode bears, usually found along the West Coast. Yet a white grizzly, whose colouring is due to a natural genetic variation, is rare. There has been little to no documented evidence of such bears in the region. Until Nakoda.

“Having a white grizzly around Canada’s flagship national park is akin to having a unicorn out in nature,” John E. Marriott explains. Marriott, a wildlife photographer based in the Bow Valley area, recalls his first time seeing Nakoda as a young bear approximately five years ago in the spring of 2020. “It would have been five in the morning, mid-May, and just starting to get light,” he says. “I remember coming around a corner on the Trans-Canada and seeing up ahead a white grizzly bear—quite a stunning sight.” In the years to come, Nakoda became well-known. She spent much of her time in frontcountry around the border of Banff and Yoho National Parks, just west of the Lake Louise townsite. She was regularly seen along the railroad and the Trans-Canada Highway, the main thoroughfare through the Bow Valley. Photographers, social media influencers, and tourists and regular people alike began to flock to the area to catch a glimpse and capture a photo of the mythical white bear.

The excitement set off alarm bells in Marriott’s head. He is a co-founder of Exposed Wildlife Conservancy, an organization which advocates for apex predators like Nakoda in Western Canada. “I was already well aware of the dangers of roadside bears becoming too habituated,” Marriott says. Roadside bears that have become habituated and have stopped being wary of human presence may wander closer to the road than they would otherwise. These bears may also be trying to access food and avoid large male grizzlies in the backcountry. Bears like Nakoda in the frontcountry of national parks, with a habitat fragmented by a national transportation corridor, will have more interaction with humans and are more at risk.

After his first sighting of Nakoda near the Trans-Canada, Marriott promptly alerted Parks Canada of her whereabouts. This would be the first of a number of conversations Marriott had with Parks Canada about Nakoda over the years. In 2021, Nakoda’s mother was struck and killed by a vehicle on the Trans-Canada Highway. In 2022, Nakoda’s sister was also struck and killed by a vehicle on the same highway, having lived in a similar home range to that of Nakoda. Marriott feared that Nakoda would meet the same fate.

In May 2024, I started a job as a server in Yoho National Park near a village called Field in British Columbia, wherein there are around 200 permanent residents. One day while at work, I looked out the window to see a white blur of fur, four legs with the signature hump of a grizzly on top. I knew it was her. She didn’t once look up at me as I stepped outside. Her head remained bowed down, scavenging for dandelions adjacent to the small mountain road outside our front door. I stared in amazement as two small faces peered out at me: her newborn cubs, maybe months old. They stumbled playfully behind Nakoda’s lead. I watched with my colleagues, all of us transfixed, as they wandered by. Female grizzlies with cubs can be particularly defensive and dangerous to humans, so we made sure to keep a safe distance. Even so, Nakoda did not once acknowledge our presence, not even a glance in our direction. Did she know that we were there?

In the subsequent days, I spent my commute to and from work distractedly gazing to the roadside, desperate to catch a glimpse of her and the cubs again. I hoped that as my car sped along the highway, I would be lucky enough to spot the blur of white fur again above the dark pavement. That spring, there was even more buzz surrounding Nakoda because of her newborn cubs. It can be difficult to pinpoint a grizzly’s exact age, but some estimates put her at about seven years old when she had given birth to her first litter. While conservationists stress the importance of protecting grizzly bears in the parks, there is even more emphasis on protecting female breeding grizzlies— sexually mature female grizzly bears who produce offspring every three to five years. “Female grizzly bears are at the heart of it all because the breeding females are the ones who keep the population going,” Marriott explains. “In particular in the Rocky Mountains, but also elsewhere throughout their range, it’s very important to have mature, smart, intelligent females that know their range and are able to teach their young ones how to then go out and survive.” Across Western Canada, the grizzly bear’s range is now full of roads and people and industry. First-time moms like Nakoda aren’t always successful in keeping their first litter alive and unharmed. To many, Nakoda’s cubs pointed to her potential future as a breeding female grizzly. The cubs breathed new life into the possible population of grizzly bears. But all too quickly, that hope vanished.

Weeks after I had seen Nakoda and her cubs wandering outside my place of work, news arrived on a June morning: with red-rimmed eyes and shaking hands, my housemate sat me down to relay to me that the two young cubs had been struck by a vehicle on the Trans-Canada Highway. Twelve hours later, on June 6, 2024, Nakoda, the great white grizzly bear of the Bow Valley, was struck in a second collision on the highway. Park employees watched her run into the forest, limping slightly. She succumbed to what the wildlife specialists believe were untreatable internal injuries on June 8, 2024.

How, and why, did this happen? A rare white grizzly, a breeding grizzly, killed by a vehicle on the highway. In the Canadian Rocky Mountain Parks, a UNESCO World Heritage site, a place that is supposed to be an ecological safe haven. In a cruel twist of fate, Nakoda and her cubs were killed in vehicle collisions on the same stretch of highway where her mother and sister were also killed by vehicles, according to Exposed Wildlife Conservancy. “I remember the sorrow that week,” Marriott says of the period when the tragic news reached Canmore. “Other photographers and conservationists feel a tremendous sense of sadness, of despair, of helplessness.”

Nakoda was the fourteenth documented grizzly bear to be killed by humans in the Canadian Rocky Mountain National Parks since 2019. She is also the sixth recorded breeding female to die in the Lake Louise, Yoho and Kootenay Field Unit since 2020. As grizzlies have one of the lowest documented reproductive rates of all terrestrial mammals in North America, the loss of several breeding females is devastating for the entire ecosystem. In May 2025, about a year after Nakoda’s death, two more female grizzlies were killed on train tracks in Banff National Park. Perhaps vehicle collisions are an inevitable outcome for frontcountry bears in the national parks. Nevertheless, the tragedy of Nakoda illuminates a larger crisis brewing in the Canadian Rockies: the parks system is failing to protect frontcountry grizzlies from death at the hands of humans.

Sorrow rippled through the Rockies at the news of Nakoda’s death, and outrage swiftly followed. An open letter, penned by the Exposed Wildlife Conservancy in the aftermath, alleges that the human-caused deaths of grizzlies in the Rockies since 2019 were preventable, and caused by what they perceive to be a combined lack of action from Transport Canada, Parks Canada, the railway company Canadian Pacific Kansas City and the federal Government of Canada. “I just knew she [was] going to end up dead,” Marriott says about Nakoda. “You have to be proactive.” He explains that there are ways to protect frontcountry wildlife along highways: creating and reinforcing lower speed limits or creating habitat patches further back to entice wildlife away from the road, for example.

Amy Krause, a media representative for Parks Canada, wrote in an email to Maisonneuve that the organization does have safeguards in place to protect frontcountry bears like Nakoda, like swiftly moving bears to the “safe” side of wildlife fences along the highway when they’re exposed. Parks Canada staff had been fixing wildlife fencing and trying to encourage Nakoda to stay away from the roadside when she was struck. The team watched over her from 2022 to 2024 and had given her a GPS collar. Krause also described efforts like electrifying the fencing in Yoho National Park to discourage climbing and putting in a no-stopping zone and speed reduction on part of the Trans-Canada to protect Nakoda and her cubs. “Together, we can contribute to the successful coexistence of people and wildlife. Keeping wildlife wild is a shared responsibility. Observe speed limits and always drive with caution,” she added.

The Parks Canada mandate and charter states: “we protect and present nationally significant examples of Canada’s natural and cultural heritage, and foster public understanding, appreciation and enjoyment in ways that ensure the ecological and commemorative integrity of these places.” To break it down: their mandate is twofold—to protect, yet also to present. To preserve the ecological integrity of the parks, the lands, waters and animals. And at the same time, to promote enjoyment of the parks through recreation and tourism. Parks Canada has certainly done an excellent job at enticing visitation with the promise and brand of alpine enjoyment. The townsite of Banff alone, during the peak season in July and August 2024, saw an average of more than twenty-seven thousand vehicles per day at the main entrances, far surpassing its traffic jam threshold of about twenty-four thousand vehicles per day at the entrances combined.

Perhaps more than ever before, the mountainous national parks are presented alongside an image of Canadianness, a vision of national identity associated with uncharted, rugged wilderness. “Wilderness is a persistent myth of Canadians,” Robert Jago, a freelance journalist who works in Indigenous politics, explains. Generations of popular Canadian media have idealized a lonely, untouched landscape. Canonical works like Farley Mowat’s Never Cry Wolf describe a solitary figure, seemingly always of European descent, navigating an uninhabited land absent of human presence. The Group of Seven, synonymous with Canadian artistic identity, focused on portraying an untamed and barren Canadian landscape. Even so, wilderness can be complicated to define. According to an annex from the year 2000 to the Canada National Parks Act, “wilderness areas” in national parks are regions that “exist in a natural state or that are capable of returning to a natural state.” The concept of a natural state is similarly broad and unspecific. In a 2023 article in the journal Architecture_MPS, researchers Felix Mayer and Piper Bernbaum look back on the origins of Banff National Park in the 1880s, describing how emerging philosophies at the time such as transcendentalism and American romanticism shifted popular views of unsettled spaces across North America; whereas wild spaces were once viewed as an antagonist to the colonial mission of settlement, now they were seen as offering an escape from the confines of religious and social hierarchies. Thus, Canadian “wilderness” and land in a “natural state” were glorified and became deeply tied to North American identity.

Jago suggests that in fact there is very little actual untouched wilderness south of the sixtieth parallel in Canada. Many plants, for example, in areas perceived as wilderness are not there naturally; they had originally been cultivated by people, he explains. However, propagating the notion of Canadian wilderness completely erases Indigenous presence and impact on the land. “Once you erase Natives from the equation, it’s basically Canada resetting the clock on history and pretending that all of that stuff didn’t happen,” Jago mentions. “So all the places where we used to live, all the things that we did, all the impact that we had on the land is annihilated, and is wiped out of history.”

The romanticization of Canadian wilderness is especially in vogue as a resurgent streak of Canadian nationalism has begun to bear its fangs, focusing on national symbols more than building an economy that can stand up to America in the era of Trump and trade wars. Introduced in April and implemented in late June, the Government of Canada launched the Canada Strong Pass, intended to promote travel and tourism within Canada’s borders. The pass included free access for visitors to all of Canada’s national parks, including to the Rocky Mountain National Parks. The promotion of Canada’s national parks at a time like this sends a clear message—parks and protected lands are political. “Wilderness,” and the connotations that it has with national identity, power, and access, is being wielded as a tool to garner support for the Canadian project under threat.

In a 2017 article published in the Walrus—following the release of Parks Canada’s Discovery Pass that similarly granted free entry to all national parks that year—Jago describes how the fantasy of Canadian wilderness eclipses the displacement of Indigenous peoples and the capture of their territories. He uses the term “green colonialism” to describe the theft of land for so-called environmental protection. Indeed, the Stoney Nakoda were displaced and alienated following the creation of what is now known as Banff National Park.

The Canadian national parks system was not created to protect wilderness. In 1883, workers from the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) company “discovered” the Cave and Basin hot springs, which led to the formation of the Banff Hot Springs Reserve. The railway company and the federal government were motivated to maintain the hot springs, with the aim of transforming the site into a travel destination, thereby boosting traffic on the CPR and increasing railway profits. In 1887, the area of protected land expanded and was named Rocky Mountains Park of Canada, Canada’s first national park, created by the federal government. Both the CPR and the Canadian government envisioned the financial success of Banff as a popular tourist destination; thus the Banff townsite and its unique surrounding “natural” environments were promoted in other parts of Canada and the world. Tourism bodies used the maintenance and presentation of a “natural” park environment as justification to displace, control, and ultimately exploit the Indigenous communities in the area.

According to a 2006 article by Theodore Binnema and Melanie Niemi in the journal Environmental History, George A. Stewart, the park’s first superintendent, wrote in his first annual report: “it is of great importance that if possible the [Indigenous] should be excluded from the Park. Their destruction of the game and depredations among the ornamental trees make their too-frequent visits to the Park a matter of great concern.” Subsistence hunting performed by the Stoney Nakoda in the park not only contradicted the (then-named) Department of Indian Affairs’ attempts to “civilize” and assimilate Indigenous people; it also challenged the tourist’s perception of a “natural” environment as a site of recreation and consumption, rather than as a place of productive labour. Binnema and Niemi detail how Stoney Nakoda hunters were blamed by Parks Canada officials for the depletion of game, although the building of the CPR, fires caused by rail vehicles and other settler activity led to much of the reduction in game in the Rockies.

Game laws at the time were designed to align with the interests of sportsmen visiting to hunt; these policies reflected a code of ethics that had been created and upheld by British American, white, male sports hunters who lived in urban areas. This is how the ethos of the national parks system came to be: the primary goal was to appeal to the tourist. The Canadian federal government also removed the Stoney Nakoda from the land that became the Rocky Mountains Park of Canada. Communities were moved to the Morley Reserve (the present-day community of Mînî Thnî), near the national park. Restrictions introduced in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries banned the Stoney Nakoda from hunting in the park. The establishment of the park and the forced removal of the Stoney Nakoda was a total disruption to ways of life, causing deep harm and a loss of cultural knowledge that extends across generations.

Since the creation of what is now known as Banff National Park and Canada’s national park system, the federal government has made some efforts towards reconciliation with Indigenous peoples. Today, Parks Canada works with the Indigenous Advisory Circle (IAC) for Banff National Park, established in 2018. In an email statement in July to Maisonneuve regarding the work of the IAC, Parks Canada explains that, “the IAC supports Parks Canada efforts to learn from and respect Indigenous perspectives, priorities, and stewardship practices in park management.” The IAC has advanced several projects, including the first Indigenous-led ceremonial bison harvest in the park since the park’s creation. The group currently includes members from the Stoney Nakoda Nations (Bearspaw, Chiniki, and Goodstoney), the Siksika, Kainai, and Piikani First Nations, the Tsuut’ina First Nation, and the Otipemisiwak Métis Government, Rocky View Métis District. The Parks Canada statement notes that the agency is dedicated to advancing initiatives that support Indigenous cultural connections, leadership and stewardship practices in Banff National Park.

Parks Canada’s James Eastham, in an email to Maisonneuve, lists a number of efforts implemented by the agency in the Banff and Yoho National Parks to connect and restore high-quality bear habitat and prevent human-wildlife conflict, including by: building alternate routes for bears near railway collision hotspots; building wildlife crossings and fencing along the Trans-Canada; prescribed fire and other techniques that create open areas where plants that grizzlies eat can grow; implementing seasonal access restrictions and group access requirements on some trails to cut down on disturbance; and studying how wildlife deaths can be minimized through speed limit reductions in some places. Eastham adds that those who had spent time trying to manage Nakoda, and protect her safety by moving her away from the highway, had grown fond of her as well. “Her death has been devastating for the team that was so deeply invested in trying to prevent this outcome,” he writes.

At the same time, conservation efforts in Banff National Park exist alongside touristic promotion. Marriott says that Parks Canada hasn’t implemented enough recreational restrictions to match the boom in visitation and protect ecological integrity. “We’ve seen little pieces of progress,” Marriott says, “but then the flip side of it is we’ve just seen visitation grow and grow and grow.” There’s an irony in people travelling to the Rocky Mountain National Parks in pursuit of natural beauty, whilst relying on the infrastructure and industry actively destroying it. For people like me who are fed up with the poisons and ills of modern society, the rejuvenating value of mountains and glacial lakes have been advertised as the antidote, and we go to seek it.

What do we find? Beauty, yes, but also the death of fearsome grizzlies, the recession of great glaciers, fires engulfing forests. For many, a deep climate anxiety arises, sparked from witnessing these scenes in a national park, an area that is supposed to be protected and monitored so that ecosystems can thrive. For the future of grizzly bears in the Canadian Rockies, Marriott says the bears need habitat security. “Go to Lake Louise, and tell me where the secure habitat is for grizzly bears,” he says in frustration, noting that though they do exist, there are few. “Where they can go right now where they know for sure they’re not going to run into a human,” he says. Eastham explains that there have been several efforts to address these issues, including the creation of the Lake Louise Area Strategy. “A series of actions, including trail use restrictions, seasonal closures, trail re-routing and the construction of wildlife underpasses have been implemented to help connect critical habitat patches throughout the Lake Louise area and improve connectivity for wildlife,” he writes. For Marriott, and many other conservationists, part of the solution is for Parks Canada to play a larger role, with more staff, more resources, and increasing the number of national parks and other protected lands.

Yet protection is not, in and of itself, the solution. Jago contends that the creation of parkland is an underhanded way to remove land from Indigenous stewardship. “Those are productive lands for Native people,” he says. “Turning them into parks makes it difficult for us to access them.” The establishment of what is now Banff National Park meant the exclusion of the Stoney Nakoda from the land in order to protect the Euro-Canadian tourist’s experience of the “natural environment.”

In the days after I saw Nakoda and her cubs, I spent a lot of time thinking about her. Wondering how she saw the road: an encroachment on her home, an obstacle to teach her cubs to navigate, a dangerous place, a haven from large male grizzlies, somewhere to access food, or simply another facet of her habitat? Perhaps it is feckless for us to try to inhabit the mind of a wild animal, to take an apex predator focused on survival and protecting her cubs and project human thoughts and feelings onto her. I was left with a lot of questions after my time in the Rockies. How to resolve the tension between curtailing overtourism and limiting accessibility to outdoor spaces; how to keep crowds away from animals so that they can thrive, while also encouraging people to love such animals and fight for their livelihood.

Today, a host of groups are working to radically reframe our relationship to parks and protected lands. West of the Rockies, there is a proposed national park reserve in the South Okanagan-Similkameen in British Columbia. The national park reserve designation means that there are ongoing Indigenous rights claims in the area. Indigenous people can continue to practice traditional spiritual activities on the land, and they may work with Parks Canada to manage the area. In Banff National Park, Parks Canada is committed to supporting Indigenous stewardship in collaboration with the IAC and Indigenous peoples. Yet, so much is still to be done if the ecological and cultural integrity of the Canadian Rockies is to be protected for future generations.

Settlers and tourists traveling through the Rockies to seek respite or an escape to wilderness must reframe their relationship to land. Natural areas are not there for our vacation; they are not an escape from the nine-to-five routine, from the incessant rat race, or from the toils of contemporary capitalism. We are also deeply embedded in and living in relation to the landscapes we inhabit, even when we think of ourselves as just passing through. Just as we use the Trans-Canada Highway to drive from point A to point B, Nakoda used that same road to forage for food and to stay away from predators. Just as grizzly bears and other wildlife have adapted to human presence, we must also adapt to respect the presence of wildlife around us. Driving the Trans-Canada—on my way to work, to a trailhead, to the grocery store, I saw those three faces for the rest of that summer. Nakoda’s beady brown eyes, framed with white fur. They stayed with me on the peaks, at the lakes, in flowery rolling meadows—alive in my memory, and in everything around me. ⁂

Saylor Catlin is a writer based between Montreal and Chicago. She is passionate about exploring ecophilosophy, equity and justice in her work.